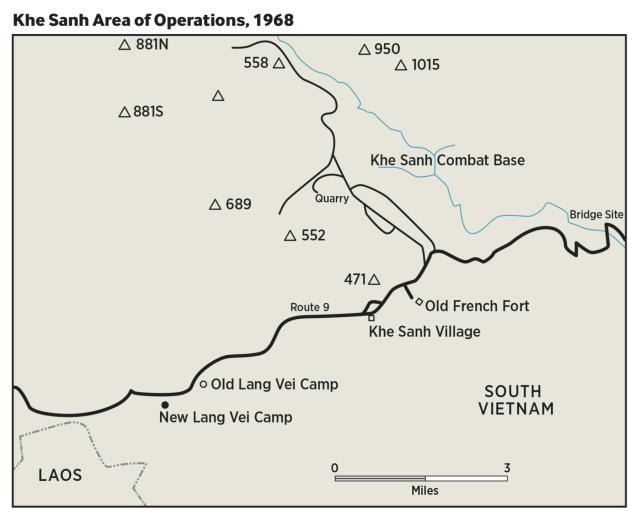

On 8 July 1968, U.S. Marine Corps Major General Ray G. Davis met privately with Lieutenant Colonel Archie Van Winkle on isolated Hill 689, about two miles west of the recently abandoned Marine combat base at Khe Sanh. Their conversation beside a small dust-blown landing zone would be brief, largely because the hill was surrounded by hundreds of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers relentlessly trying to drive the Americans off. The two officers were keenly aware it would not be long before enemy mortar shells arrived.

Those looking on could not have known at the time that this brief encounter would mark a defining moment in Marine Corps history. These last few days in the 15-month-long battle for Khe Sanh were ushering out the controversial way Marines had been asked to fight the war, initiating a new, more mobile offensive strategy. Their meeting also was bringing to a head a macabre dilemma plaguing Marines—particularly at Khe Sanh.

In Paris, representatives from Hanoi and Washington D.C., who had begun talks two months earlier on how to end the war, also were keenly interested in Hill 689. The American negotiators were concerned that annihilation of this last outnumbered Marine battalion would give their adversary an early upper hand in the discussion.

Marines had first occupied the Khe Sanh plateau and airfield two years earlier, after unsuccessfully trying to convince U.S. Army General William Westmoreland, commander of all U.S. forces in Vietnam, that it was a bad idea. The rainy, socked-in weather and short supply lines for the enemy led the Marines to believe it was a trap—perhaps even a reenactment of the Viet Minh victory over the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, which broke French control over Indochina. Westmoreland, however, hoped for just such a scenario, drawing enemy forces out into the open and using superior U.S. airpower to reduce them in numbers that would force Hanoi to the negotiating table.

Fierce Combat, Back-Channel Negotiations

In May 1967, NVA combat troops massed on hilltops a few miles to the west of the Khe Sanh Combat Base, preparing to overrun the installation and drive the Americans out of the mountains there. Marines immediately attacked and eventually occupied two hills, 861 and 881 South. The following month, a Marine battalion attempted to dislodge the NVA from Hill 689, suffering heavy losses before returning to the combat base. What would become known as the Hill Fights proved to be some of the deadliest combat of the war.

About the time Marines were fighting on Hill 689, President Lyndon B. Johnson privately reached out to Soviet Premier Alexi Kosygin to sound out North Vietnam’s willingness to discuss a peace settlement in the war. The Soviet Union was a benefactor of North Vietnam in its struggle against the Americans, and so this gesture was recognized immediately as a lack of personal resolve on the part of the U.S. Commander-in-Chief and did not bode well for U.S. forces in the field.

In late January 1968, the NVA again moved against the Khe Sanh Combat Base, in numbers not seen before. Over the next 77 days, Marine positions were subjected to intense artillery, mortar, and rocket fire daily, as well as several sizable and costly infantry ground attacks. Khe Sanh had long been cut off from ground transportation, and only survived by the employment of inventive methods to reinforce and resupply the base and its outposts by air.

During the first four months, NVA forces around Khe Sanh were subjected to 100,000 tons of bombs (equivalent to the explosive power of five Hiroshima-sized nuclear weapons) and nearly 160,000 large-caliber artillery shells. The CIA estimated that enemy replacement troops arriving at the Khe Sanh battlefield averaged from 190 to 380 a day, meaning the total number of NVA soldiers engaged in the battle over that period could have been as high as 44,000.

In early April, U.S. Army and Marine forces arrived to break the siege. Despite thousands of enemy forces remaining in the general area, President Johnson declared U.S. victory at Khe Sanh, simultaneously announcing he would not run for reelection in November, a decision considered by many as a tacit admission of failed strategy in fighting the war.

Continue Operations . . . Indefinitely

Marine and Army generals petitioned Westmoreland to abandon Khe Sanh immediately. He denied the request and ordered Americans to continue operations in the area indefinitely. In mid-April, Marines patrolling the northeast slope of Hill 689 came under fire from well-camouflaged NVA positions, taking heavy casualties. After hours of anxious fighting, the Marines were forced to move back off the hill, leaving more than 30 bodies that would not be recovered for a week. This tragedy was reminiscent of another encounter, just outside the base in February, when 19 dead Americans had been left behind and would not be recovered for over a month, the enemy using their exposed bodies as bait to draw out more Marines.

In May, four NVA regiments, assisted by heavy artillery, came within a mile of the combat base in an attempt to capture it before being stopped by a Marine reaction force. It was apparent to most U.S. military leaders that the situation at Khe Sanh remained as untenable as ever and General Westmoreland’s plan to break the spirit of the North Vietnamese had failed.

Following his promotion to Army Chief of Staff in June, Westmoreland’s replacement, General Creighton Abrams, called for the immediate destruction and evacuation of Khe Sanh. This would take several weeks, and so to keep the highly aggressive NVA at bay, Americans fought a series of costly battles in the surrounding hills.

Under cover of darkness on 5 July 1968, a U.S. truck convoy slowly crept east from Khe Sanh along a briefly reopened roadway with the last remains of the combat base and its inhabitants. Marine units on Hill 881 South and Hill 689 were supposed to have been helicoptered out days earlier; however, as the result of a well-conceived enemy ambush, eight American bodies remained just outside the defensive barbed wire on 689.

The situation worsened the following morning when a Marine platoon went to retrieve its dead. The enemy was waiting in well-concealed bunkers and spider holes around a “kill zone” where the bodies lay as bait. As Marines tried desperately to retrieve their fallen comrades, more were killed and wounded. By dusk they were forced to break contact, leaving behind several more dead Americans.

Bodies Beyond the Perimeter

On 6 July, dismayed that this problem had prevented the last Marines from being flown out of Khe Sanh, the commander of the 1st Battalion, 1st Marines, Lieutenant Colonel Archie Van Winkle, ordered the remainder of the battalion, including his headquarters unit, airlifted from Hill 558 to Hill 689 to deal personally with the dire situation. Last to arrive was a company from Hill 881 South, whose men had fought unsuccessfully that afternoon to recover the body of a Marine just outside the perimeter, from under yet another baited enemy ambush.

Van Winkle set up his new command post in a cave-like hole below the northeast rim of the hill. Due to unrelenting attrition since late May, his command was now a “battalion” in name only, closer in troop strength to about 500 men, rather than the customary 1,200.

The following night, hundreds of NVA soldiers approached. Lead members called out to the Marines in English, mimicking wounded Marines and corpsmen who had found their way back. The ruse allowed them to approach within several yards before bursting through the barbed wire and flowing to the right and left down the Marine trench lines. The attackers quickly overwhelmed Marine fighting holes and bunkers, but their effort to take the crest of the hilltop and the battalion command post stalled. The Americans counterattacked and reclaimed all their positions.

This was the situation on 8 July 1968, when Major General Ray Davis flew to Hill 689 to speak privately with Lieutenant Colonel Van Winkle, the most pressing topic being what to do about all the bodies now outside the perimeter. Captain Richard Camp, there as part of General Davis’ staff, would later say:

I remember the look on the faces of the troops. They had tried, unsuccessfully, to bring the bodies back, and each time they were ambushed by the NVA, who had “staked” out the remains. I could tell that the Marines did not want to go back out there again. It was painful to watch.

After Davis departed, Van Winkle returned to his command post, telling his operations officer, Captain James P. McHenry: “Mac, he’s not going to tell me that we have to get those bodies, but he is not going to let us leave until we do.”

Khe Sanh historian Ray W. Stubbe later wrote that dead and wounded Americans were left behind repeatedly at Khe Sanh because the Marines could not easily adapt to the “atrocious battlefield environment, yet refused to abandon their fallen without a fight. Time and time again tradition and loyalty overcame reason or objectivity.”

At Khe Sanh, the NVA used dead and dying Americans as deftly as any weapon in their arsenal. Once in such traps, Marines became victims of their stylized methods of fighting and reacted the way the enemy knew they would when struggling to retrieve a lost buddy, with emotion and bravado, effectively turning the Corps’ most cherished virtue of Semper Fidelis into its deadliest vulnerability.

Brotherhood of Mutual Trust

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was common for brief truces to occur at the end of battles, allowing opposing sides to gather their dead. But by World War II this courtesy no longer existed, and the abandoned remains of an adversary were frequently left unburied, or interred in mass graves, often more for hygienic than humanitarian reasons.

In December 1950, NATO forces had made a desolate departure from the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea where, enduring sub-zero temperatures, they were quickly becoming encircled by more than 120,000 troops from the People’s Republic of China. First Marine Division Commander Major General O. P. Smith ordered the Marine dead transported out along with the wounded, slowly working their way south through rough mountainous terrain and a gauntlet of Chinese ground and artillery attacks until they reached safety at the port of Hungnam. Of the more than 2,500 U.S. and United Nations soldiers involved in that battle, only 1,050 survived.

It may have been this test of will and loyalty, under the most grueling circumstances, that established a “tradition,” and a de facto policy, of never leaving another behind—dead or alive. Whatever the advent of that doctrine, it was understood by every Marine going to Vietnam that they would not be left there, a commitment that bound them together in a brotherhood of mutual trust. While encouraging this notion to foster esprit de corps, the Marine Corps had no official policy, largely because such guidelines were unnecessary before so many of these agonizing tactical situations arose at Khe Sanh.

Colonel Frederic Knight, a Marine battalion commander in 1968, later wrote that the Third Marine Division commander, Major General Rathvon Tompkins, General Davis’ immediate predecessor, had a policy of recovering bodies as part of “the deep tradition of the Marine Corps taking care of each other, dead or alive.”

This policy of bringing back all KIAs, Knight said, created problems for commanders who often “wanted to disengage to reduce casualties and seek a more advantageous tactical situation, but under that stricture, could not.” Knight later advocated a policy of “weighing our traditions . . . against the utilitarian principle of the greatest good for the greatest number, and actions taken accordingly.” General Davis seemly supported his predecessor’s policy, and so Van Winkle and his officers set about devising a scheme to recover their dead Marines.

The final plan unfolded on the moonless night of 9 July. A “box of steel” would be created around the bodies using coordinated fire from machine guns, mortars, and close-air support bombers, while two-person “body snatcher” teams, well camouflaged, faces smeared with black paint, and carrying a single body bag, moved into that box to recover a designated corpse. The mission was over in 30 minutes and all but two of the dead were found and recovered. This time, no one was killed in the effort, and the last Americans departed the hill on the afternoon of 12 July 1968.

True to Their Code

The grim meeting between Davis and Van Winkle was remarkable in other respects. Both men had fought in the South Pacific during World War II—Van Winkle in a Marine aviation squadron and Davis fighting on Guadalcanal, and later receiving the Navy Cross and Purple Heart for his actions on Peleliu.

During the Korean War, both men had been with the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, during the aforementioned fighting at the Chosin Reservoir. Then-Lieutenant Colonel Davis and Staff Sergeant Van Winkle would each earn the Medal of Honor, just a few weeks apart; both, at great personal peril to themselves, rescuing Marines trapped by the enemy. Van Winkle would spend several months recovering from wounds.

Richard Camp, who commanded a rifle company at Khe Sanh during the siege, recalled the same steady nerves Davis and Van Winkle still possessed 18 years after their heroics in North Korea. Camp and Captain Jim Jones, who recently had led a rifle company during a critical battle just a few weeks before on Fox Trot Ridge, about six miles east of Hill 689, were watching the two “old-timers” meet when an outgoing artillery round just barely cleared the ridgeline:

The sound sent Jim and me scrambling for the nearest shell hole. A minute later we looked up as the two Medal of Honor recipients stood looking down at us, kind of shaking their heads. They hadn’t even blinked an eye . . . needless to say, Jim and I were embarrassed.

Over the coming months, General Davis would oversee innovative tactical changes for his Marines that resulted in some battlefield successes, as in the case of Operation Dewey Canyon II against the NVA in the heavily fortified A Shau Valley. Camp would recall: “He had a superb tactical ability—probably the finest division commander the Corps has ever had—I was fortunate enough to have seen him remotivate an entire Division so that it became a winning team.”

However, after Khe Sanh and the Tet Offensive, and as the peace talks continued, Marine combat ground forces were systematically withdrawn from Vietnam. In May 1971, the First Battalion, First Marine Regiment, which had also been the last out of Khe Sanh, would now be the last out of South Vietnam.

Davis and Van Winkle, whose valor at the Chosin Reservoir significantly maximized the number of Marines and corpsmen who would survive, found themselves nearly 20 years later face-to-face on a hilltop in Vietnam in the midst of abandoning what would become another historically significant position. Again, surrounded and outnumbered by the enemy, they sought to save as many of their men as they could, while honoring the unwritten code to bring their fallen brothers back to their families.

On the hill that day were junior officers who had been experiencing their first combat over the preceding year, like Jim Jones, later the 32nd Commandant of the Marine Corps, and Richard Camp who, after a distinguished career, would go on to become Deputy Director of History for the National Museum of the Marine Corps. Also on Hill 689 that day was Lieutenant Ray Smith, who had led his company in a critical counterattack on the night of 7 July that helped break the NVA assault. Smith later would rise to the rank of major general, leading the First Marine Division into Baghdad in 2003. Witnesses to this dramatic moment between two legendary members of the “Greatest Generation,” these three men would be prepared a few years later to shoulder the enormous challenges of leading the next generation of Marines into 21st century.

Sources:

Maj Mirza Munir Baig, USMC, Memorandum, 23 December 1968, Headquarters, U.S. Military Assistance Command, Thailand, Joint United States Military Advisory Group, Thailand, to Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps, Historical Records Branch, G-3 Division.

Richard Camp, email to author, 7 March 2023.

Brig Gen Hoang Dan and Captain Hung Dat, Highway 9—Khe Sanh Offensive Campaign: Spring and Summer 1968 (Hanoi: Vietnam Institute of Military History, 1987).

First Marine Regiment Command Chronology, July 1968.

William Conrad Gibbons, The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War: Executive and Legislative Roles and Relationships, Part IV: July 1965–January 1968 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 1995).

Hoang Ngoc Lung, The General Offensives of 1968–69 (McLean, VA: General Research Corporation, 1978).

James P. McHenry, The Last Battalion Out of Khe Sanh (unpublished memoir, 2013).

John Prados and Ray W. Stubbe, Valley of Decision: The Siege of Khe Sanh (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2004).

Jack Shulimson, U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Defining Year, 1968 (History & Museums Division, Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps Washington, DC, 1997).

Michael Sledge, Soldier Dead: How We Recover, Identify, Bury and Honor Our Military Fallen (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005).

Ray W. Stubbe, Battalion of Kings: A Tribute to Our Fallen Brothers Who Died Because of the Battlefield of Khe Sanh, Vietnam, 1st ed. (Wauwatosa, WI: Khe Sanh Veterans, 2005).

Ray W. Stubbe, B5-T8 in 48 QXD: The Secret Official History of the North Vietnamese Army of the Siege at Khe Sanh, Vietnam, Spring, 1968 (Wauwatosa, WI: Khe Sanh Veterans, 2006).

Ray Stubbe, letter to author, 6 August 2012.