Who Can Hold the Sea: The U.S. Navy in the Cold War, 1945–1960

James D. Hornfischer. New York: Bantam, 2022. 480 pp. Images. Biblio. Index. $36.

Reviewed by William Hannigan

Who Can Hold the Sea will be the last book authored by James Hornfischer, who, sadly, passed away last year. He wrote several naval history classics during a spectacular 20-year run, including The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors and Neptune’s Inferno. This book is much broader in scope—a 15-year period versus a single battle or series of battles. With a few exceptions, it also lacks the vivid descriptions of individual heroism he captivated us with in previous masterpieces.

The story begins with Moscow-based diplomat George Kennan’s “long telegram,” authored six months after the end of World War II, urging vigilant containment of the Soviet Union. President Harry S. Truman and Defense Secretary James Forrestal, unlike many old hands at the State Department, understood the Soviets and their surrogates in China could not be reasoned with. Thus the “domino theory” and the strategy of containment were embraced early in the nuclear age.

By this time, the unseemly U.S. interservice battles were reaching a fever pitch, as civilian and uniformed leaders were dealing with deep postwar budget cuts. The percentage of GDP dedicated to defense spending had plunged from approximately 44 percent to about 8 percent in just two years.

The foremost interservice battle was between the Navy and the newly created Air Force—culminating in the “Revolt of the Admirals” and the B-36 controversy.

Many believed the advent of nuclear weapons as “just another weapon” rendered the Navy and the Marine Corps obsolete. The wishful thinking was that vast sums of money could be saved by building strategic bombers and cheap nukes. Armed conflict going forward would be nuclear, and the United States had a monopoly. Of course, the monopoly was short-lived, and it was not long before the Marine Corps was landing at Inchon and the Navy was saving countless Army and Marine lives with carrier-based close-in air support.

One thread throughout the book is how often the United States considered using nuclear weapons during this period, including in an effort to save the French from losing Dien Bien Phu in 1954. On hearing this recommendation, President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded, “You boys must be crazy.”

Hornfischer chooses several innovations and innovators to illustrate the technological advancements driving the Navy’s strategy: specifically, nuclear power and the development of a “true” submarine force. The pugnacious genius and political savvy of Hyman Rickover looms large in these chapters. Hornfischer also highlights those behind the development of the Sidewinder and Polaris missiles. Submarines carrying Polaris intercontinential ballistic missiles solidified the Navy’s role as the lead element in the nation’s nuclear triad. Multiple types of aircraft capable of carrying nuclear weapons were developed and deployed to the fleet in an almost frenzied manner.

Critical leaders and relationships during this tumultuous era are featured throughout. Especially interesting is the relationship established between Ike and three-term Chief of Naval Operations Arleigh Burke.

Sharon Hornfischer wrote about her husband’s final book: “Please regard this text as a last letter from an old friend, and please understand that your friend was simply not able to wrap up the story with his usual finesse and depth of detail.” Some parts of the book do read like a series of short stories, albeit fine short stories, not completely stitched together; however, Who Can Hold the Sea will still take its place next to Hornfischer’s other often-read gems on my shelves.

Mr. Hannigan is a retired telecom and tech exec who served six years in the submarine service on board the USS Jack (SSN-605) during the Cold War. He is a member of the Naval Institute Board of Directors.

Old Breed General: How Marine Corps General William H. Rupertus Broke the Back of the Japanese in World War II from Guadalcanal to Peleliu

Amy Rupertus Peacock and Don Brown. Guilford, CT: Stackpole Books, 2022. 448 pp. Maps. Biblio. $29.95.

Reviewed by Lieutenant Colonel Timothy Heck, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve

Every Marine is a rifleman, and every Marine’s best friend is his or her rifle. The indelible words of “The Rifleman’s Creed” are imprinted in the psyche of Marines during initial training. The author of those words, then–Major General William H. Rupertus, has largely avoided the spotlight and histories of World War II. Rupertus, who joined the Marine Corps in 1913, commanded the 1st Marine Division in the Pacific longer than any other general. Nevertheless, his story is relatively unknown. His granddaughter, Amy Rupertus Peacock, has attempted to restore him in Marine Corps historiography with Old Breed General. The book provides an interesting perspective on his career and place in Marine Corps history, but it must be read with a critical eye.

The main narrative arc of the book precedes the Guadalcanal landings through to his passing in March 1945. Told in chronological fashion, with vignettes offering Japanese perspectives and those of junior Marines, Rupertus’s story is presented as “literary nonfiction,” which the authors describe as including dialogue “to supplement the great historical points.” Though not explicitly stated, this dialogue is largely imagined. Furthermore, Rupertus as a literary character is prone to self-reflection and analysis, which the authors use to provide his backstory and prewar career. The result is a book that jumps back and forth, and it is not always clear why.

Rupertus’s prewar career was, in many ways, like that of his contemporaries. Duties in Latin America and China were interspersed with assignments in Quantico and Washington, D.C. Most relevant to the book, and mentioned frequently in the text, was his service in Shanghai in the late 1930s. There, Rupertus served in the International Settlement with the 4th Marine Regiment as the Japanese attacked and pillaged the city. His prewar experience with the Japanese is repeatedly presented as giving him a sense of what to expect on Tulagi and Guadalcanal. Later combat at Cape Gloucester and on Peleliu also are recounted in some detail.

Rupertus’s role on Guadalcanal, especially during the Battle for Henderson Field from 23 to 25 October 1942, is well told and comprises the bulk of the book. Coverage of his command in Australia, at Cape Gloucester, and on Peleliu is relatively short compared to the treatment Guadalcanal receives. As he was the commanding general in these later battles, and given the relative dearth of works on Cape Gloucester or Peleliu in comparison to Guadalcanal, the imbalance is disappointing.

The authors’ access to Rupertus’s diary, letters, and personal artifacts is impressive, as is the amount of supplemental archival research conducted, particularly the use of oral histories and personal papers. Readers will note the lack of in-text citations, making verification of statements and details difficult. Furthermore, the literary nonfiction approach obfuscates the historiographical value of the book. Readers also will find editing errors, with units mislabeled, inconsistent terminology, and unnecessary use of “Japs” in non-dialogue text. Furthermore, many of the maps and images are fuzzy or appear to be scans from other books.

Overall, Old Breed General opens the door for further study of Rupertus. His story is relatively unknown, despite his crucial role in World War II. This book should serve as the start of a deeper analysis of him as a product of his era and as a commander. Those looking to read about a significant general officer all but lost to history would do well to pick up this book.

LtCol Heck is the deputy editorial director of the Modern War Institute at West Point. He is an artillery officer in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserve, currently assigned as a joint historian with Marine Corps History Division. He is coeditor of On Contested Shores: The Evolving Role of Amphibious Operations in the History of Warfare (Marine Corps University Press, 2020).

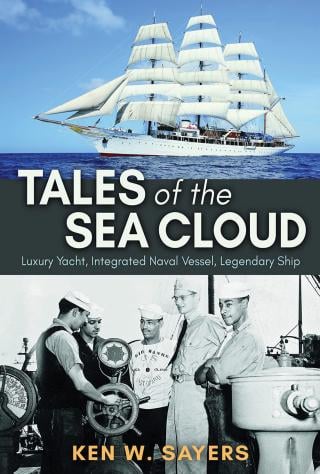

Tales of the Sea Cloud: Luxury Yacht, Integrated Naval Vessel, Legendary Ship

Ken W. Sayers. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2021. 251 pp. Photos. Biblio. Index. $35.

Reviewed by Commander Ian Starr, U.S. Coast Guard

I confess, I approached this book with skepticism. As titled, the main protagonist is a thing, a German yacht that changed owners, military services, and nations and is now enjoying employment as a cruise ship. Could this thing command attention across 250 pages? By the end, author Ken Sayers had me convinced.

Tales of the Sea Cloud is not just about a thing: it is a story about the intersection of a vessel, a man, and a revolutionary idea. It is a story of a four-masted barque, a Coast Guard lieutenant, and the first big step toward racial integration in the U.S. military since the Civil War.

The vessel started life in 1931 as the Hussar V, built alongside battleships and submarines in the Germaniawerft shipyard of Kiel, Germany. The barque was purchased as a new plaything for Edward Hutton, cofounder of one of Wall Street’s largest firms, and his wife, Marjorie Post, a wealthy businesswoman. When the couple eventually divorced, Marjorie kept the barque. In 1935, she married Joseph Davies, the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, and renamed the vessel Sea Cloud, and for a number of years the ship played host to dignitaries while the clouds of war gathered on the European horizon. When World War II enveloped the United States, the Navy leased the Sea Cloud from Marjorie for a nominal fee of $1 per year and gave the vessel to the Coast Guard for use as a weather station in the North Atlantic. In 1944, after two years of service in the Eastern Sea Frontier, the Sea Cloud embarked Coast Guard Lieutenant Carlton Skinner as executive officer.

Skinner’s narrative arc is described, in Sayers’ telling, as a “butterfly effect,” in which unknowable tremors of an earlier incident define his life and provoke radical change. When he served as executive officer of the USCGC Northland (WPG-49), he witnessed a top-performing African American steward named Oliver Henry be denied a rate change to motor machinist, despite exceptional performance and technical capability. Skinner refused to take no for an answer and fought back against the headquarters-level decision, eventually securing the rate change for Henry, who went on to serve a full and successful Coast Guard career. This taste of victory set Skinner on a new path and cemented in his mind a vision for what a racially integrated service could accomplish.

Skinner’s “revolutionary” idea—that a racially integrated crew could perform just as well as nonintegrated crew (if not better)—was fully realized when he fleeted up to command of the Sea Cloud in late 1944. With approval from both the Navy and Coast Guard, Lieutenant Skinner maintained a crew that was 50 to 65 percent black and, most important, assigned duties, responsibilities, and watches with no regard to skin color. This experiment, the first of its kind since the Civil War, was a complete success. Sayers does not pull any punches on that account, diligently chronicling the ways in which the military employed minorities but, more frequently, failed (and fought) integration over the decades.

The book skillfully charts the lives of the Sea Cloud and Lieutenant Skinner, including their lives after the brief interlude of World War II. Skinner went on to command the USCGC Hoquiam (PF-5), also with an integrated crew, and eventually served as the governor of Guam. The Sea Cloud regained her masts and returned to civil service after the war, trading hands and names multiple times over the decades. But that brief intersection of man and machine during World War II was a pivotal moment that helped turn the tide toward racial integration of both the Coast Guard and the Navy.

CDR Starr is a cutterman with more than nine years of sea service, including as deck officer and executive officer on board medium-endurance cutters, navigator on board a Navy guided-missile destroyer, and commanding officer of two Island-class patrol boats. He currently is serving as a detailee to the Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs.