The Curtiss JN biplane—invariably known as the Jenny—was the most widely flown U.S. Army training aircraft in World War I. It also was flown in large numbers by U.S. Navy and Marine Corps pilots and by Canadian airmen during and after the war.

American aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss previously had produced only pusher aircraft, with the engine and propeller mounted behind the pilot. Realizing the need for more-conventional, tractor-engine planes, he hired Benjamin Douglas Thomas, who had worked for the Avro and Sopwith aircraft firms in England, to help develop a trainer for the U.S. armed forces.1 Their collaboration led to the model J biplane, built by Curtiss. That aircraft was evaluated as both a landplane and single-float seaplane.

An improved N model followed, then came the definitive JN series. Interestingly, the first Navy JN was a twin-engine aircraft, referred to as the “Twin JN.” It, too, was evaluated as both a landplane and a twin-float seaplane but was rejected by the Navy, which had accepted two of the twin-engine aircraft. Of the ten “Twins” that were built, the Army obtained the other eight, two of which saw action on the Mexican border in 1916–17.

The Navy then procured the standard Jenny, which flew as a landplane and sea-plane. The seaplane had two small wingtip floats and a single center float, with a few having twin main floats. The biplane had two open cockpits. During its production run numerous improvements were made to the aircraft.

Beyond the basic trainer, 90 gunnery trainers were acquired by the Navy (JN-4HGs).2 They had a single machine gun synchronized to fire through the propeller arc and one or two machine guns on a Scarff ring at the after cockpit; camera guns could be used in place of the machine guns. Another Jenny variant was a flying ambulance that could accommodate a stretcher in a raised fuselage housing.3

The JN-series procurement for the Navy and Marine Corps continued after the war. The Sea Services’ buy totaled 255 aircraft of the reported 6,813 Jennys built by Curtiss and other firms in the United States and Canada.4 The U.S. Navy and Army flew them until 1927.

On 15 May 1918, the Post Office Department began using Jennys when the first scheduled airmail service was instituted between Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, and New York. Army pilots flew the planes for the first two months of the service until the department was able to hire its own pilots. That same year a postage stamp was issued depicting a Jenny. In error, the biplane was printed upside down—the most famous error in U.S. postage stamp history. About 100 stamps were printed before the mistake was noticed. Those stamps subsequently have sold at auction for as much as $1.5 million each.

The Jenny performed admirably as a trainer for U.S. and Canadian military pilots during the war and became well known throughout the United States in that role. But after the conflict it achieved iconic status: Being easy to fly and with surplus Jennys readily available to civilians as well as former military pilots, it was seen everywhere as a barnstorming stunt and “air circus” aircraft and as a mail carrier.

1. Thomas also helped to design the Thomas Moore S-4 Scout aircraft, a single-seat advanced trainer flown by the U.S. Army and Navy; the latter aircraft, configured both as landplanes and floatplanes, were designated S-5.

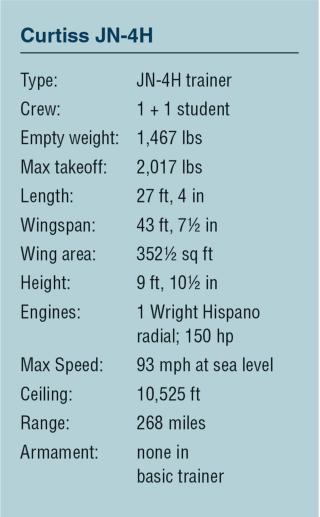

2. The suffix letter “H” indicated the 150-horsepower Wright Hispano engine.

3. Details of the various JN configurations are in Peter M. Bowers, Curtiss Aircraft 1907–1947 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979), 143–68.

4. Frequent exchanges of aircraft orders between the Army and Navy still make some production numbers questionable.