The history of naval architecture is replete with designs that, however innovative, never made it out of the concept phase. Some, like the large surface effect ship, seemed promising but could not deliver their designed performance even as smaller prototypes Others, like the sea control ship escort concept, were cancelled because of budget cuts. Still others, however mercifully, never made it off of paper.

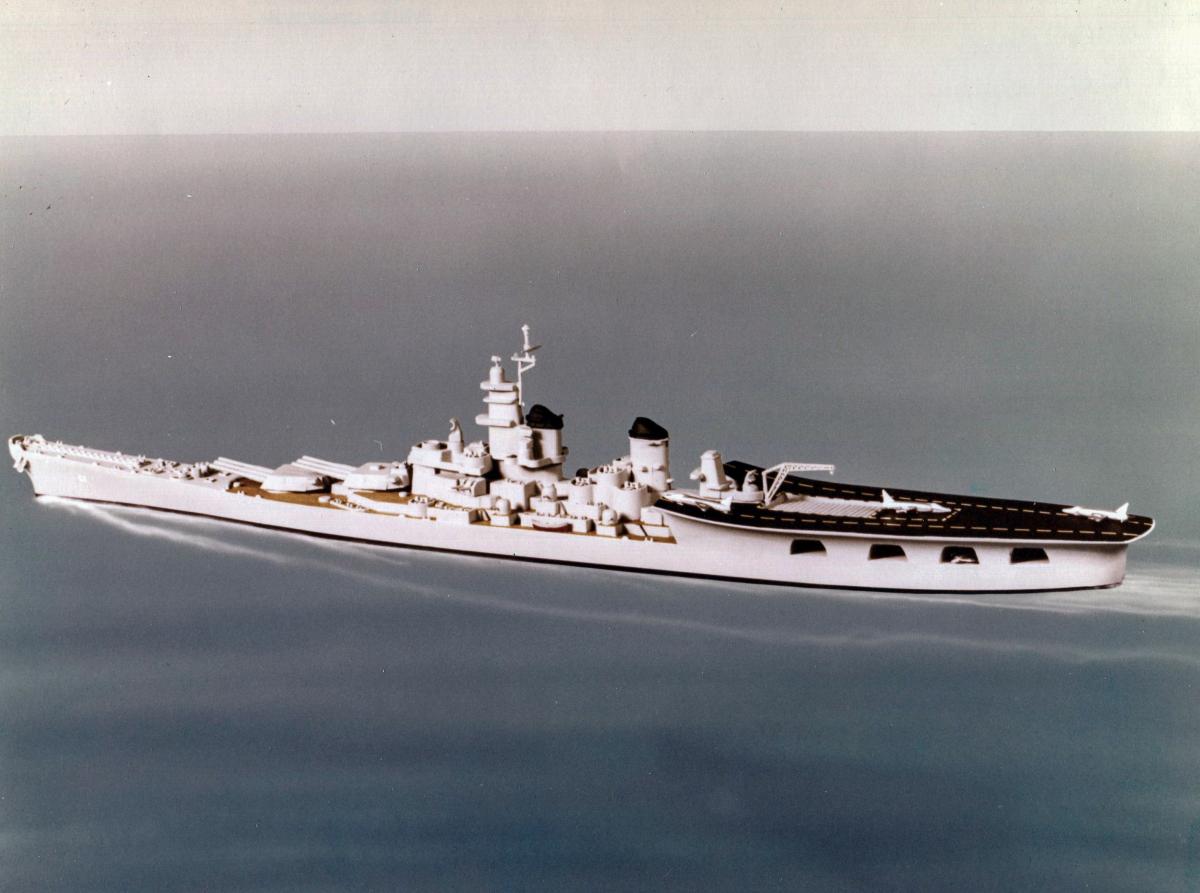

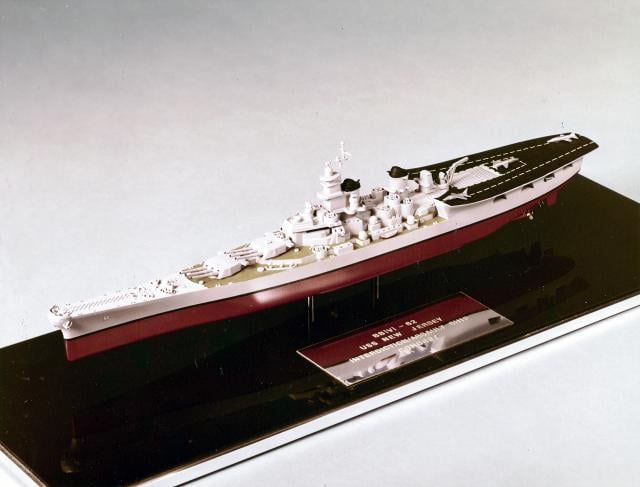

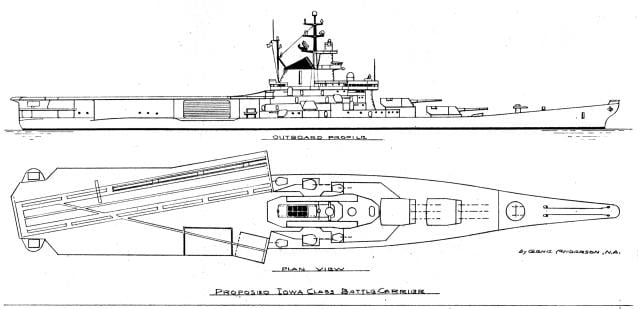

Such was the Iowa-class interdiction/assault ship, a late-1970s proposal that would have transformed the four battleships into "battlecarriers"—one-ship power-projection force with a landing deck for short take-off vertical landing (STOVL) aircraft operations.

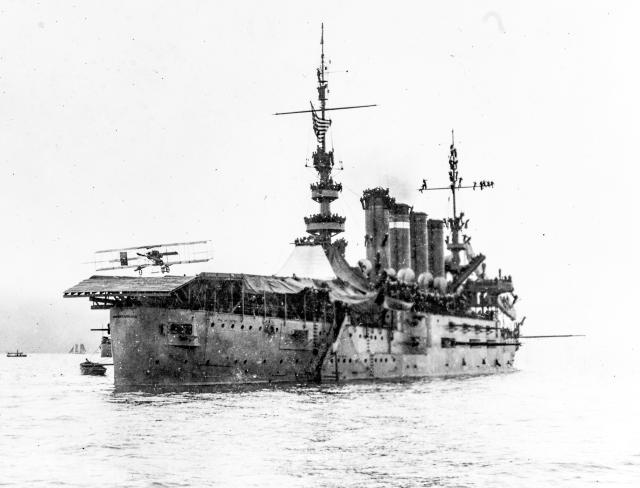

The idea of adding a flight deck to a capital ship was not a new one. In November 1910, Eugene B. Ely was the first to fly an aircraft off of a warship; in February he became the first person to land on one, putting his Curtiss pusher down on a temporary wooden landing platform erected on the armored cruiser Pennsylvania's (ACR-4) stern.

(Naval History and Heritage Command)

As a proof-of-concept, the idea was sound, at least when the aircraft were made of wood and fabric. During the First World War, most carriers built served seaplanes, but the idea of an aircraft launch/recovery platform on a capital ship was further developed and refined. The British modified battlecruiser HMS Furious during construction, sacrificing armor and armament to accommodate a flying deck forward.

Neither Furious nor another cruiser conversion, the Vindictive, proved particularly successful, owing to difficulties caused by the presence of the warships' superstructures. Interestingly, Furious was later converted to a full-length deck carrier, but Vindictive was re-converted back into a heavy cruiser.

During the interwar period, several countries, including the United States, considered and abandoned aviation cruisers. It was necessity that would revive the concept during World War II.

Following the disastrous loss of its carriers at Midway, Japan rebuilt two of its obsolete battleships into hybrid carriers as an emergency stopgap measure. Both Ise and Hyūga had their rear turrets removed and flight decks and hangars constructed in their place. Neither had much success as carriers before they were sunk at Kure in 1945.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

Naval architect Gene Anderson had the opportunity to study the Ise post-war. In 1981, he recalled:

Immediately after the war, I was sent to Japan for duty with Physical Damage Team One of the U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey to study atomic bomb damage at Hiroshima. Since the Ise was sunk up to her main deck in a bay nearby, I was able to study this hybrid warship at close range.

While with the survey, I had the opportunity to discuss this warship with members of the Naval Analysis Group. From this discussion, I learned that the Ise was reported to have never launched an aircraft in combat and that the conversion of a battleship into half of an aircraft carrier was at the time considered a failure. As one member of the group put it, “It was a silly waste of a battleship.”

There were many reasons given why this conversion failed. At the time, it was felt that the flight deck lacked length and area for the high-performance Zeros to be launched and recovered in spite of two catapults and a proven arresting gear system. The high massive “Pagoda” mast, the broad stack, and the main mast support superstructure just ahead of the flight deck all had combined to generate such severe wind turbulence across the flight deck that it made flying operations extremely difficult and unsafe while the ship was steaming at proper launch and recovery speeds. It was also pointed out that both the lack of highly experienced pilots and fuel late in the war also contributed to this failure.

During the war naval planners on the other side of the Pacific had considered converting two Iowa-class battleship hulls then under construction—Illinois (BB-65) and Kentucky (BB-66)—to full-deck carriers, but the expense proved too great and the two ships were ultimately cancelled. Following the Korean War, the four ships of the class that had been completed were laid up in reserve. A proposal to convert the ships to amphibious assault carriers in the vein of the the Thetis Bay (CVHA-1/LPH-6) was reviewed in 1961, but any ideas for conversion were ultimately dropped—that is, until the 1970s, when the Navy began the Sea Control Ship (SCS) program.

With the Vietnam War winding down, the Navy sought to modernize the fleet and produce a lighter ship that could carry aircraft to effect control of the sea. As Admiral Zumwalt wrote to one petty officer in 1973, conversion of the Iowa-class battleships had been considered and studied, but all had reached the same conclusion: the ships were too old, too manpower intensive, too expensive to operate, and too costly, especially in comparison to the new sea control ship design.

By 1978, the SCS program was dead and the Soviet navy was resurgent with their successful deployment of Kiev-class flight-deck cruisers; within a year the Iranian revolution would change the dynamics of the Middle East. With these changes, American planners began to revisit the idea of modernizing the Iowas. There now was a need not just for power projection, but also for an "all-weather fire support from a warship that could engage successfully protected targets located in the littoral ribbons of the world." The idea for the interdiction/assault ship was born.

One of the more radical proposals for this one-stop-shop for force-projection called for rebuilding the Iowa-class battleships to provide that support. Charle E. Myers described the rationale for doing so in a 1979 Proceedings article:

The concept of operations for the interdiction ship involves working inside the ten-fathom line (less than 60-foot depth) where she would be relatively immune to interference from submarines. The draft of the ship at 55,000 tons is 35 feet. The aircraft carrier providing air cover will operate from a station 50 to 200 miles at sea to minimize exposure to enemy air and shore defenses. Air cover and spotting sorties can easily be provided from such proximity.

Commenting early in 1980, a program manager at Martin Marietta, who were developing the concept, offered his own assessment. These converted interdiction/assault ships, in his opinion,

could carry an effective antiair warfare suite, a contingent of airmobile marines, vertical missile launchers and long-range missiles, and six 16-inch guns forward. Thus configured, the IAS would become an excellent crisis control ship—an integral military part of a new foreign policy able to deal out flexible responses matched to the strategic and tactical situation. Ordered into a trouble area, the IAS would create an awesome, meaningful presence. Asked to initiate a naval blockade, the IAS could engage any challengers with an incredible array of options—ranging from her simple presence, to the ominous slewing of her massive guns toward the object of her interest, to clearing off the intruder’s bow with the sweep of a ten-ton salvo, to boarding the trespasser with airborne marines, to destroying an enemy with gunfire or missiles.

Reactivation of the battleships would be done in stages: in Phase I, the battleships would be reactivated with only minimal modifications to get them into to service as quickly as possible. After long and fierce debate in Congress in 1980 and 1981, Phase I was approved, and the four battlewagons were recommissioned with much fanfare.

(U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive)

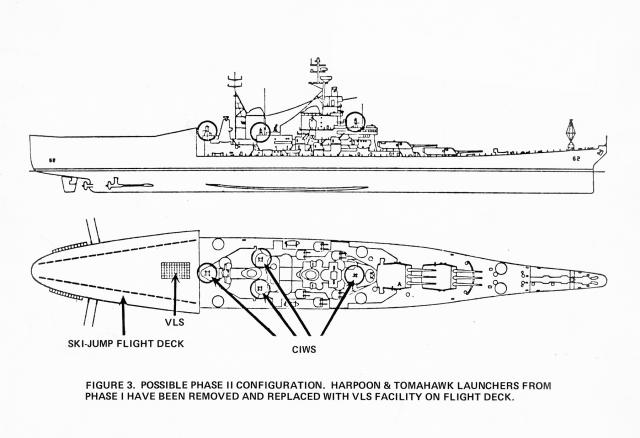

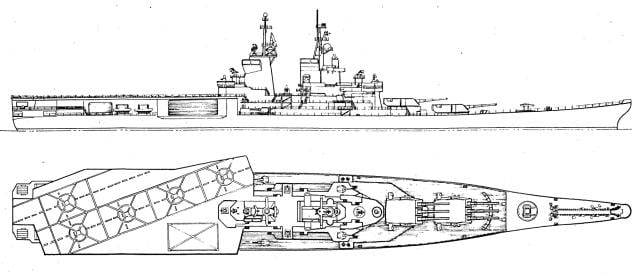

Phase II would have been dramatic and transformative. As Myers described later, among other modifications, the converted interdiction/assault ships would have offered:

- Six 16-inch guns that could fire a variety of modern munitions

- A 320-tube vertical launch system (VLS) capable of firing Tomahawks, Standard Missiles, ballistic missiles, and the Army Tactical Missile System family

- Flight and hangar decks in place of the after turret, for various mixes of AV-8B Harriers, heavy-lift and attack helicopters, and MV-22 Ospreys

- Accommodations for SEALs and 800 Marines for short periods

- Logistics spaces and machine shops

- Medical facilities and operating rooms

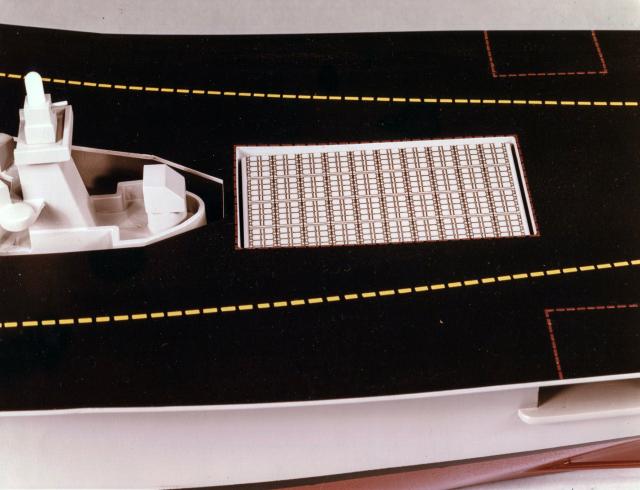

On the pages of Proceedings, designers worked to refine the concept. Martin Marietta's version featured twin ski-jumps for the launch of STOVL aircraft. Harold Pulver suggested refining the design to include more weaponry like the 5-in./54 cal. Mk-45 automatic weapon system and several Phalanx close-in weapon system and a variety of missiles.

Gene Anderson, the naval architect, improved on Pulver's design, extending the flight deck, reconfiguring the stack and superstructure to reduce turbulence during flight operations, and adding back in a ski-jump that ended up looking much more like the Soviet Kievs.

Ultimately, and unsurprisingly, the design went nowhere. By 1984, the plan was all but dead. Following Desert Storm, the Navy recapitalized its assets and decommissioned the Iowas, though Charles Myers continued to push for the conversions as late as 1995.

Today, the four battlewagons are museum ships, having never gotten the transformative overhauls that would have turned their iconic profiles into the capital ship of the 1980s.