Commander Paul Talbot likely felt a heavy weight of responsibility resting on his shoulders as he sat in the command chair on the bridge of the destroyer USS John D. Ford (DD-228) during the late hours of 23 January 1942. He was about to lead the U.S. Navy into its first sea battle since the Spanish-American War of 1898. Talbot was in command of Destroyer Division 59, composed of his flagship and three other destroyers—the Pope (DD-225), Parrott (DD-218), and Paul Jones (DD-230). The force was moving through the night to attack a group of Japanese ships off Balikpapan, Borneo, in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia).

The war was less than two months old, and American sailors had become accustomed to hearing only bad news from around the Pacific front. Numerous islands and territories had fallen under enemy control since the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. A bleak future seemed in the offing. The British were retreating from enemy forces down the Malay Peninsula, and General Douglas MacArthur’s U.S. and Filipino soldiers in the Philippines were making a last stand on the Bataan Peninsula.

U.S. Admiral Thomas Hart was the overall naval commander of ABDA, a multinational force made up of American, British, Dutch, and Australian elements. The command was set up to provide for the joint defense of the Malay Barrier—Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies. Allied leaders saw the territories as a critical line to stop the Japanese from advancing into the Indian Ocean and toward Australia. The command was thrown together hastily, with little planning and thin resources—especially in aircraft.

Hart organized his fighting ships into a task force under the command of his subordinate, Admiral William Glassford, who was determined to do whatever possible to slow the advancing enemy. The best opportunity came in late January 1942, when the Japanese were making initial advances toward the oil-rich Dutch section of Borneo. Much of the oil was located near two critical ports, Tarakan and Balikpapan. The Japanese forces seized Tarakan on 11 January 1942 and were ready to strike Balikpapan less than two weeks later.1

The operation required the Japanese to enter Makassar Strait, a narrow body of water separating Borneo from the nearby island of Celebes to the east. An invasion force of 16 transports plus an assortment of small escorts slipped out of Tarakan during the night of 20–21 January.2 U.S. submarines and PBY Catalina patrol planes provided some sighting reports before further reconnaissance was hindered by deteriorating weather conditions over the strait. The Japanese transports were accompanied by a powerful escort force composed of the light cruiser Naka and ten destroyers under the command of Admiral Shoji Nishimura. Sporadic air attacks by Dutch and American planes caused a limited amount of damage, and U.S. submarine operations were largely unsuccessful. Neither delayed or significantly hampered the invasion plans.

The air off Balikpapan was filled with a hazy smoke when the Japanese ships dropped anchor off the coast near the end of 23 January. The Dutch had set fire to oil facilities and the port area to prevent the enemy from reaping immediate benefits from their pending invasion. Troops began going ashore early the next morning to take control of key positions. The Dutch opposition on the ground, less than formidable from the start, quickly diminished. The Japanese soon were in control of the entire Balikpapan area.3 However, they were about to experience some unwelcome guests at sea.

‘Attack Enemy Off Balikpapan . . .’

The anchored transports off Balikpapan were an inviting target for a U.S. naval attack, but assembling a suitable strike force proved to be a challenge. Various ABDA warships were out of position on convoy escort duty or under repair and unavailable for the operation. The remaining ships—the light cruisers USS Marblehead (CL-12) and Boise (CL-47) plus six U.S. destroyers—were anchored in Koepang Bay off the island of Timor on the morning of 20 January when initial reports arrived of enemy movements. The location was almost 800 miles southeast of Balikpapan.

The two light cruisers were equipped with six-inch guns, but were otherwise nearly opposites. The Marblehead was timeworn, obsolete, and built based on inferior World War I technology. A member of the Pacific Fleet based at Pearl Harbor, the Boise was among the newest ships in the U.S. Navy and the only warship in the region with radar. Convoy escort duty had brought her to the Philippines in early December. She subsequently was trapped there at the start of hostilities and pressed into service on the front lines.

Admiral Hart directed the ships to move to the Postillon Islands south of Celebes, about half the distance to Balikpapan. Fate dealt the Americans a terrible blow as the ships proceeded north. Admiral Glassford’s flagship Boise hit an uncharted coral reef while passing through Sape Strait on the morning 21 January, scraping her bottom in an unfortunate accident largely due to outdated American maps. The modern warship was out of the fight and eventually departed for repairs in the United States. The old cruiser Marblehead became hobbled by mechanical problems. She could only follow behind the group at a slower pace.

Admiral Hart was still determined to attack the Japanese with whatever forces he could. The actual attack now would be carried out by only four warships of Destroyer Division 59 under the under the operational control of Commander Paul Talbot. The Marblehead, now with Glassford on board, and the destroyer Bulmer (DD-222) stayed behind to cover their retirement.

The seagoing commanders received the official order from Hart to proceed with the mission just after noon on 23 January, while the ships were still south of the Postillon Islands. The admiral previously had passed along some initial sighting information. He told Talbot, “Good luck going in . . . No further information . . . Attack enemy off Balikpapan . . . If no contacts by 0400 zone time retire at best speed . . . Godspeed coming out.”4

Critical to the success of the mission was the ability of the destroyers to arrive off Balikpapan undetected. The ships moved north in a single column passing Makassar Town on the southwestern coast of Celebes off the starboard side at 1632. Commander Talbot then pointed his force slightly east. “. . . it was decided to proceed toward Mandar Bay during the three remaining hours of daylight in order to deceive enemy observation aircraft expected to be encountered in the vicinity,” he explained. “Later information proved this plane to be our own.” He turned back west shortly after sunset for the final run at 27 knots across Makassar Strait to Balikpapan.5

The four Clemson-class destroyers were obsolete by current standards, having been commissioned in 1920–21.6 Each ship was equipped with four open-mount 4-inch guns and 12 torpedo tubes organized in four triple sets. While the torpedo battery looked formidable on paper, the weapons were partially mitigated by the poor arrangement of having two sets of tubes mounted on each side—positioning allowing for only six tubes to be fired off one side. Newer destroyers featured centrally located torpedo batteries able to train off either port or starboard. The Japanese destroyers guarding the invasion force were larger, more powerful, and of newer design. The enemy also had the 5.5-inch guns of Admiral Nishimura’s flagship Naka.

Commander Talbot’s orders for the pending battle were sent to the other destroyer commanders by blinker light messages. “Primary weapon torpedoes. Primary objective transports. Cruisers as necessary to accomplish mission. Endeavor launch torpedoes at close range before being discovered.”7 Talbot exhorted his sailors to “use initiative and determination.” He also passed along an assortment of additional instructions, including information about torpedo settings and retirement plans.

The weather conditions created poor visibility as the destroyers moved through the darkness in Makassar Strait. Continuous waves pounded the flagship John D. Ford, occasionally making it a struggle for crewmen to stay on their feet. Even Talbot could not see much through the thick haze as he rested in his command chair on the bridge. At the critical juncture leading up to the battle, Talbot was suffering from a severe case of hemorrhoids. He was thought to have lost a considerable amount of blood, but the officer refused to relinquish his command and the responsibility of leading the men into battle.8

A Burning Beacon

An unusual fog appeared with an oily feel and chemical smell as midnight passed, ushering in the first minutes of 24 January. A short time later, lookouts spotted a series of strange lights in the distance ahead, including what seemed to be a fire near the surface, glowing reflections in the sky, and lights appearing at irregular intervals. The burning cargo ship Nana Maru, damaged earlier by Dutch planes and now an abandoned wreck, was the source of some of the illumination.

The U.S. sailors found eerie conditions as they made their final approach into the Balikpapan area. The port was a mass of flames surrounded behind by the burning oil facilities. A thick black smoke was pouring out into Makassar Strait for some 20 miles, leaving a lingering stench of burning oil.9 The smoke and thunderstorms in the strait hindered Japanese lookouts while providing a perfect cover to hide the approaching Americans.

At 0035 lookouts on board the John D. Ford spotted enemy ships, reporting to the bridge, “Several enemy destroyers ahead, in column, passing from starboard to port, distance 3,000 yards.”10 Talbot quickly altered course to starboard while tense sailors trained torpedo tubes toward the enemy waiting for the order to fire. The last ship in the passing column flashed a blue light recognition signal toward the Americans. There was no response. The enemy destroyers continued to move off into the distance. Admiral Nishimura’s ships were searching for a lurking enemy—not the approaching destroyers, but a submarine.

Commander Talbot was unaware the Dutch submarine K-XVIII already had attacked the Japanese ships off Balikpapan. Her capable skipper slipped through the initial escorts, operating on the surface due to the poor conditions, about three hours before the U.S. ships arrived. She carried out two torpedo attacks on the Naka. Nishimura’s flagship escaped damage. However, the cargo ship Tsuruga Maru was hit by one torpedo around 0045 and turned into a burning wreck.11 The Dutch submarine played no further role in the battle.

The attack prompted Admiral Nishimura to send his destroyers east into Makassar Strait to search for the submarine. The move created an almost perfect opening for Commander Talbot’s force to sneak into the anchorage undetected.

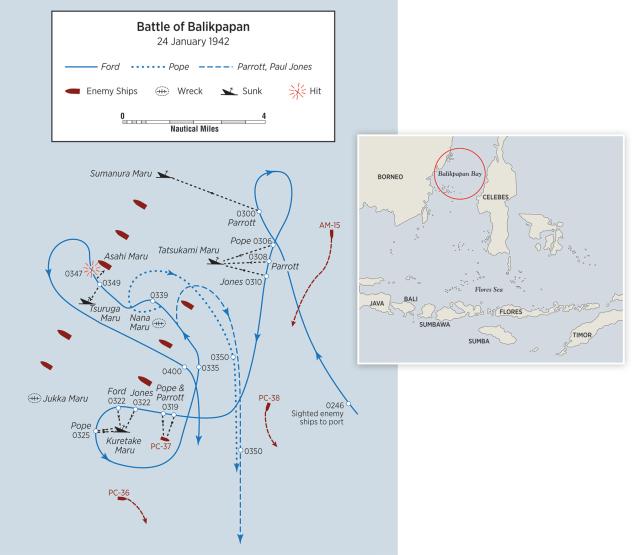

American lookouts sighted the main targets at 0246—two rows of transports, anchored about five miles off the entrance to the harbor in a southwest-to-northeast direction. The ships were perfectly silhouetted by the fires burning in the background.12 An assortment of small patrol ships—three old World War I–era patrol torpedo boats, four minesweepers, and four subchasers—surrounded the transports.13

The John D. Ford led the column into the midst of the enemy ships followed in order by the Pope, Parrott, and Paul Jones. “The shore line had not been sighted and visibility was low due to a burning ship at sea and oil fires ashore,” Talbot later wrote. “It was extremely difficult to distinguish the type of target until close aboard, or to estimate the target angle.”14

The Parrott was the first to fire, unleashing three torpedoes from her port side toward a close target identified as a transport. The destroyer’s sailors anxiously waited for the sound of an explosion. Nothing happened. Minutes later, the Parrott fired a spread of five torpedoes at a ship about 1,000 yards off her starboard side with the same non-result. Initially thought to be a light cruiser or destroyer, the target was a minesweeper. In rapid succession, the John D. Ford fired a single torpedo at a transport, and the Paul Jones fired one at the same minesweeper targeted by the Parrott. Both attacks were unsuccessful. The poor outcome of the first pass through the enemy formation easily could have demoralized even the stoutest destroyer sailor—ten torpedoes fired at short range and no hits.

Commander Talbot was undeterred as he maneuvered his ships for a second pass at 0300. “Enemy ships were in sight at all times and many were passed close aboard,” he wrote. The Parrott fired three torpedoes at a ship off her port bow. About two minutes passed before the 3,500-ton transport Sumanoura Maru exploded into a mass of flames.

Torpedoes in the Darkness

The element of surprise was now over. The attack threw the enemy into confusion; some Japanese ship captains correctly discerned they were under attack by surface ships, but they could not tell who was friend or foe in the confusing night conditions. Others—including Nishimura—believed the attack was from a submarine. The admiral kept his destroyers searching for an underwater intruder.

The Pope, Parrott, and Paul Jones all fired torpedoes off their starboard sides in the span of the few minutes leading up to 0310. One struck and sank the transport Tatsukami Maru. By 0314 it was clear the destroyers were moving along the bottom edge of the transport columns. Talbot ordered his column to make a right turn to bring the formation back toward the southern edge of the transports. Two Japanese ships fell victim to U.S. torpedoes in the coming minutes: The 750-ton torpedo boat PC-37, apparently mistaken for a destroyer, was the target of a total of five torpedoes unleashed from the port sides of the Pope and Parrott. Three struck the small vessel, immediately sending her to the bottom. Only the John D. Ford and Paul Jones now had torpedoes left. Each fired one at a transport off the port side. The 5,000-ton Kuretake Maru, already under way, avoided both with a quick turn. But the next shot from the Paul Jones hit the merchant ship’s starboard bow, causing her to explode and sink.

The U.S. destroyers now opened fire with their 4-inch guns and few remaining torpedoes as the column looped back toward the transports at 0335. Some Japanese ships responded with wild gunfire in all directions. Talbot’s formation became separated after a series of sharp turns by the John D. Ford. The flagship continued north, moving alone among the transports. The last two ships in the column, the Parrott and Paul Jones, turned in the opposite direction. The pair were soon joined by the Pope. All three of the destroyers were out of the battle.

The John D. Ford was moving in the direction of the burning shore with her gunfire causing minor damage to various Japanese ships. The destroyer fired her last two torpedoes at three transports off her port side at 0346. At least one hit the Tsuruga Maru, sinking the cargo ship previously damaged by the Dutch submarine.15 At the same time, gunners were exchanging fire with the armed transport Asahi Maru. Sailors in the destroyer watched as shells fell close aboard. A cry suddenly came over the intercom headsets: “We’re being bracketed, port side aft.”16

At 0347 a single shell hit the after deck house, causing a small but intense fire and wounding four men. Return fire hit the transport, causing damage and wounding as many as 50 men. Approaching dangerous shoal waters near the shore, the John D. Ford swung to port, reversing course while again passing through the transport columns.

Victory—and Validation

It was now 0350. The battle was over. With the Japanese fully aware the attackers were surface ships, and with no more torpedoes to fire, the destroyers sped toward their planned rendezvous with the Marblehead and Bulmer, positioned about 50 miles south. The John D. Ford caught up with the other destroyers after initially lagging. The morning light brought the possibility of enemy airplanes, but luck was still riding with Talbot. His force escaped the Japanese all together.

Commander Talbot had “nothing but commendation” for his destroyer captains. “Their ships were skillfully handled and well fought at high speed under low visibility conditions for more than one hour in close contact with the enemy.” Admiral Hart was smiling when he joined Glassford in making a dockside visit to the returning destroyers in Surabaya, Java.17

The Battle of Balikpapan was a clear American tactical victory. A set of circumstances allowed Commander Talbot’s ships to surprise the unsuspecting Japanese, and subsequent poor decisions by Admiral Nishimura allowed the attack to flourish. The action was insignificant from a strategic standpoint, causing virtually no delays to the Japanese conquest of the Dutch East Indies. But the battle gave the beleaguered U.S. sailors in the region a much-needed, albeit small, victory—and the understanding that the Japanese were not unstoppable.

1. Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. III: The Rising Sun in the Pacific (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1948), 281–83.

2. Tom Womack, The Allied Defense of the Malay Barrier, 1941–1942 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2015), 116.

3. Paul S. Dull, A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1978), 62–63.

4. J. Danial Mullin, Another Six-Hundred (Mount Pleasant, NC: J. Danial Mullin, 1984), 119.

5. CO Destroyer Division Fifty-Nine to Commander in Chief, US Asiatic Fleet, “Night Destroyer Attack on Enemy Forces off Balikpapan, Borneo, NEI, Commencing at 1915 GCT January 23, 1942—Report on,” 26 January 1942 (hereafter cited as “Night Destroyer Attack”); Morison, Rising Sun, 285.

6. Norman Friedman, U.S. Destroyers: An Illustrated Design History (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1982), 1, 494–95.

7. “Night Destroyer Attack,” Enclosure A, 1.

8. Mullin, Another Six-Hundred, 121.

9. Womack, Defense of the Malay Barrier, 120.

10. Mullin, Another Six-Hundred, 123.

11. “IJA Transport TSURUGA MARU: Tabular Record of Movement,” combinedfleet.com/Tsuruga_t.htm.

12. Morison, Rising Sun, 287–88.

13. Jeffrey R. Cox, Rising Sun, Falling Skies: The Disastrous Java Sea Campaign of World War II (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2014), 158.

14. “Night Destroyer Attack,” 2.

15. Cox, Rising Sun, Falling Skies, 160.

16. Mullin, Another Six-Hundred, 137.

17. John Michel, Mr. Michel’s War, from Manila to Mukden: An American Navy Officer’s War with the Japanese, 1941–1945 (Novato, CA: Presidio, 1998), 49.