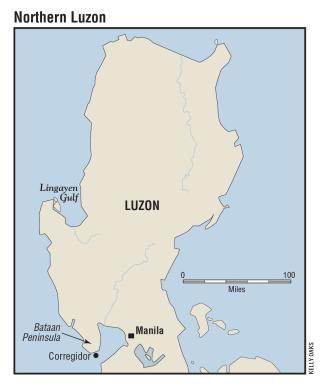

In December 1941, the U.S. Navy’s largest concentration of modern submarines was in the Philippines, with 29 based in Manila and assigned to Admiral Thomas Hart’s Asiatic Fleet.1 Hart, himself a submariner, had high expectations that they would be the primary striking element of his small fleet. Yet in the first two weeks of the war, the submarines proved ineffective against Japanese operations around the Philippines, and they had little effect when the main Japanese invasion convoy entered Lingayen Gulf on the northwest coast of Luzon late on 21 December.

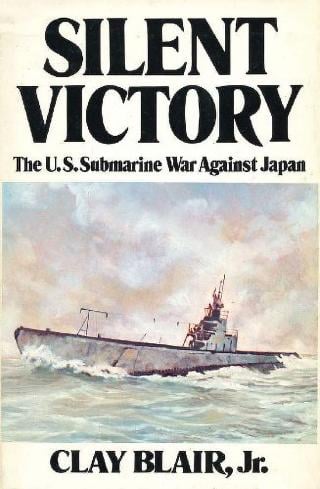

Clay Blair Jr., author of Silent Victory, long considered the definitive account of the U.S. submarine war against Japan, referred to this as the “Battle” of Lingayen Gulf.2 It was a disappointing performance to start the war. Throughout that bleak December, Admiral Hart’s submarines sank only four ships.3

It is worthwhile to assess what lessons American submariners learned from their performance in the defense of the Philippines, particularly from a little-known 1942 internal submarine force evaluation. This document, although containing many recommendations for improvement, missed the mark by not critically evaluating some key errors by the staff that wrote it. Moreover, in his discussion of the causes of U.S. submarine ineffectiveness, Blair addressed some obvious errors but proposed others of minimal significance. And both the 1942 document and the eminent naval historian failed to recognize the major weakness of Hart’s plans for his submarines.

Submarines to War

With Hart’s arrival as Commander, U.S. Asiatic Fleet, in August 1939, modern fleet-type submarines began to reach the Philippines, augmenting a squadron that had dwindled to only six submarines. Twelve fleet boats under Captain Walter “Red” Doyle were transferred from Pearl Harbor as war approached, giving Hart 23 of what were arguably the most capable submarines in the world, in addition to six aging S-class boats designed at the end of the Great War.

Commander John Wilkes had been the senior submariner on Hart’s staff since 1939, responsible for training, maintenance, and operations of the submarines. Hart reluctantly placed the more senior Doyle in charge as Commander, Submarines, U.S. Asiatic Fleet (CSAF), on 1 December, with Wilkes serving as “special advisor.” As events moved toward war, CSAF deployed two boats on 3 December on short notice: S-36 to Lingayen Gulf and S-39 near the San Bernardino Strait.4

On 8 December the Japanese struck the Philippines. General Douglas MacArthur’s air forces were decimated, and as a result, the Japanese were able to operate in the air over the islands and the surrounding seas with little opposition from U.S. pursuit planes, bombers, or reconnaissance aircraft. With Hart’s withdrawal of the majority of his small surface force to the southern Philippines and Borneo prior to the outbreak of hostilities, the Navy’s burden for the defense of the Philippines rested squarely on his submarines.5

On that chaotic first day of the war, the CSAF leadership team provided the skippers with operation orders and verbal instructions for conducting their war patrols. Within hours of these briefings the first boats were under way, headed for their patrol areas. By 11 December, 21 submarines had departed Manila to join S-36 and S-39 for operations against the enemy.

Hart quickly realized that his new senior submariner was not up to the task of wartime operational command. On 10 December, as Japanese bombers unhurriedly destroyed Cavite Navy Yard in Manila Bay, he directed Wilkes to relieve Doyle as CSAF. Doyle was placed in charge of a convoy of ships that scampered south out of Manila that evening.6

The Japanese kept the Americans off balance by skillfully executing a carefully sequenced operational plan of air attacks and landings throughout the Philippines. On 10 December, they made small landings in northern Luzon, where the submarines assigned to these areas arrived too late to engage the landing forces. Later, two boats were unable to impede a small landing convoy on the southeast coast of Luzon on the 12th.7 The Japanese intended these landings to accelerate the destruction of U.S. air power and to begin the encirclement of U.S. and Filipino ground forces.

Futility and Frustration

CSAF’s deployment plan sent ten boats, including five of the six S-boats, to the east and south of Luzon. By 21 December, they had made only three attacks, with at least one erratic torpedo and no confirmed sinkings.8 Seven boats were deployed into the South China Sea to forward areas near Japanese bases. They found more activity, making 15 attacks for four claimed sinkings by 21 December. However, at least three torpedoes malfunctioned, and only one sinking was confirmed in postwar records.9

The remaining six boats were deployed along the west coast of Luzon in defensive patrol areas. S-36 patrolled inside Lingayen Gulf until communications problems caused Wilkes to order her back to Manila on 16 December. He then shifted one fleet boat outside Lingayen Gulf.10 These six boats had no confirmed sinkings, and one skipper broke down in the middle of the action and requested to be relieved.11

After two weeks of war, Hart’s submarines had not slowed the Japanese advances, and—ominously—there were indications of defective torpedoes and missed shots on perfectly set-up short-range attacks.

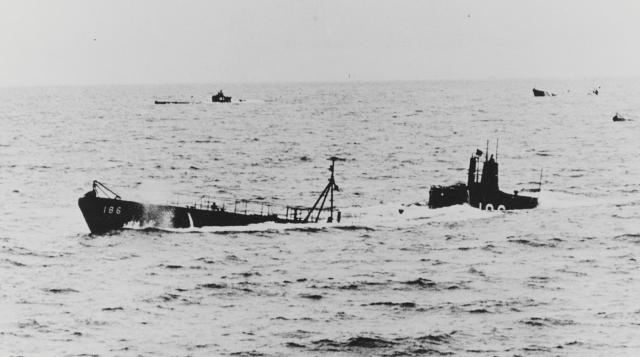

Late on 21 December, the Stingray (SS-186) was patrolling outside Lingayen Gulf and detected the primary invasion force. Getting off a contact report but no attacks, she was maneuvered with a notable lack of aggressiveness. Wilkes directed her and several nearby boats to converge on the gulf, penetrate it, and attack the landing forces. Over the next five days, six boats attempted unsuccessfully to pierce the Japanese antisubmarine cordon at the entrance to the gulf. Making primarily night surface attempts, they were detected and driven off. Only S-38 was able to enter the gulf, sinking one transport.12 Of 29 submarines available at the start of hostilities, only seven were involved in opposing the invasion.

MacArthur’s ground forces were swatted back from the beaches at Lingayen, and as Japanese troops moved south, he declared Manila an open city on 25 December. With Manila untenable as a base for further naval operations, Hart left by submarine for Java on the 26th. Wilkes and the CSAF staff followed him south on board the last boats departing on the 31st. Submarines would continue operating in and around the Philippines for four more months, with many being used on special missions to bring in supplies and ammunition or remove personnel from Corregidor. But the naval focus would primarily shift south as the Japanese closed in on their main prize: the oil and other resources of the Dutch East Indies.

Lessons But Little Critical Self-Assessment

After the failed campaigns for the Philippines and the Malay Barrier, the Asiatic Fleet’s submarines continued their long retreat, arriving in Australia in March. Wilkes and his staff immediately began working on an assessment of submarine performance to determine why their boats had been so ineffective. The 72-page action report contained a summary of the campaign and also incorporated the skippers’ perspectives, based on their individual war patrol reports.13 Some of CSAF’s main observations and recommendations were:

1. Japanese antisubmarine performance. Wilkes credited Japanese measures for disrupting his force’s operations. The Navy did not believe the Japanese had sonar on their destroyers, and CSAF was surprised by reports from its boats of escorts echo-ranging.14 CSAF also suspected the enemy’s destroyers were equipped with radar because of their proficiency in detecting boats on the surface, but radar installation on their ships did not begin until later in 1942.15 In fact, one of Wilkes’ main points in the report was that Japanese naval forces were better than expected. The Americans had underestimated their enemy.

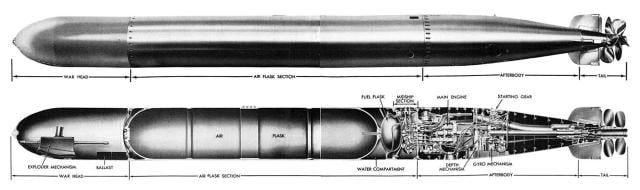

2. Torpedo performance. CSAF had enough data from its skippers by January 1942 to suspect that the Mk 14 torpedo ran much deeper than set and that its magnetic exploder could be causing premature detonations (see “Pieces of the Past,” October). Wilkes said that this was one of the primary reasons for lack of success in damaging the enemy, and he reported his concerns in January to the Navy Department.16

The Bureau of Ordnance dismissed the percentage of premature detonations as within acceptable limits and said the torpedoes ran only slightly deeper than set for the first 1,000 yards of their run.17 And with that wave of the hand from the technical authority, submarine torpedo problems were to continue to fester until the voices of exasperated skippers and the hard data they presented rose to a level that submarine force leaders could not ignore.

3. Commanding officer performance. Wilkes relieved two skippers during December.18 Later, as the campaign expanded south, he would relieve six more. He remarked that future submarine skippers would be chosen based on the ability to “produce results” and that those found unsuitable would be removed “as soon as they prove that they are incapable of inflicting damage on the enemy.”19

4. Ineffectiveness of fleet boats in shallow-water defense situations. To make best use of the fleet boats’ speed and endurance, Wilkes said they should be positioned in open water because of their ineffectiveness once the Japanese reached their shallow-water destinations and set up strong antisubmarine patrols. He attributed the poor results in part to stationing the boats in defensive areas.20 Because the enemy seemed adept at guarding against submarines at departure and destination points, he recommended positioning them to intercept along transit routes.

Wilkes also discussed the impact of the loss of control of the air, the detectability of fleet boats on the surface at night because of their large silhouettes, the opportunities lost by diverting boats on special missions to Corregidor, and the urgency of upgrading the boats with important alterations, including surface-search radar.21

CSAF’s report was a solid document with some good recommendations that would benefit the submarine force during the hard fighting to come. But it failed to take a critical look at some important operational decisions by Hart and Wilkes that might have given the submarines better opportunities for success against the Japanese onslaught.

Blair’s ‘Eight Major Errors’ Assessed

More than 30 years later, Clay Blair in Silent Victory called the submarine defense of the Philippines “abysmally planned and executed.”22 Conventional wisdom had long held that faulty torpedoes and cautious commanding officers were the primary reasons behind the poor performance of U.S. submarines in the opening campaign in the Pacific. Blair went further, describing “eight major errors” that contributed to the lack of success:

1. Faulty peacetime training. Blair faulted Wilkes and Rear Admiral Thomas Withers, the commander of the Pacific Submarine Force at Pearl Harbor, for overseeing “unrealistic” training.23 They stressed the mortal threat to submarines from aircraft, urging skippers to attack from deep using sound information only. However, only 9 percent of attacks by Asiatic Fleet submarines in December 1941 used sound-only tactics.24 Blair also decried the lack of wolf-pack tactics, but it is doubtful the Americans could have developed the required level of operational sophistication during peacetime. Blair also criticized Wilkes for failing to implement prewar long-range practice patrols, as Withers did for his force, which might have familiarized skippers and crews with the psychological effects of extended underway periods.

Blair did not mention that fear of aircraft drove skippers to remain deep during daylight, severely restricting detection ranges and reducing attack opportunities. The increased submerged operations also slowed their overall speed of advance and increased response time. Nor did he address that insufficient night surface training resulted in Japanese antisubmarine forces continually gaining the initiative, which thwarted night surface approaches and forced the submarines to submerge and evade.

2. Poor upkeep and maintenance.25 Considering that Manila is at the end of a long logistics trail from the United States that complicated maintenance, this is a bit unfair. Wilkes’ chief of staff, Commander James Fife, stated that submarines that had been in Manila for some time were “not in the best condition to start a war with. They’d been pretty well worn, and the maintenance and repair in the Philippines had never been completely adequate.”26 Although a contributing factor, it is doubtful that much could have been done to improve the situation.

3. Basing submarines in Manila. Blair opined that there were other places in the southern Philippines that could have better served as a submarine base, proposing as an option Tawi Tawi, an island province 500 nautical miles south of Manila.27 However, any advantages would have been offset by the longer distance to the scene of the expected main fight at Lingayen Gulf and a lack of air protection. In addition, the Japanese could have launched carrier raids to attack the new location, as they did against the southern port of Davao on the first day of the war. The real issue was to be able to protect Manila by retaining sufficient U.S. air power, which MacArthur had given Hart reason to expect could be done.

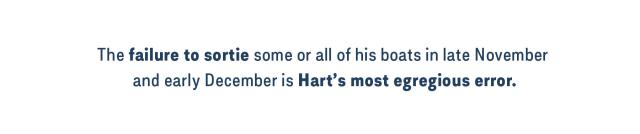

4. Failure to deploy prior to commencement of hostilities. It is difficult to understand why on the day Japan attacked only two elderly submarines were deployed outside Manila Bay ready for action. Hart fully expected war with Japan; why not order his submarines deployed, or have Wilkes send boats on practice war patrols? Blair wrote that had some or all of the boats been deployed before war started, Japanese forces concentrating for the upcoming operations likely would have been reported, leaving more time to react.28 It also would have had the added benefit of getting skippers and crews into wartime routine and learning lessons earlier. The failure to sortie some or all of his boats in late November and early December is Hart’s most egregious error.

5. Weak instructions for war.29 CSAF briefed skippers to “use caution and feel their way” on their first patrol.30 One division commander instructed them: “Don’t try to go out there and win the Congressional Medal of Honor. The submarines are all we have left. Your crews are more valuable than anything else. Bring them back.”31 Wilkes later sent radio messages to the boats urging aggressiveness to penetrate Lingayen Gulf, but skippers did not press their attempts after encountering Japanese destroyers that detected them and stole the initiative.32 It is not hard to imagine that they heard a little voice inside their heads saying: “Your crews are more valuable than anything else.”.”

6. Failure to defend Lingayen Gulf.33 Even by 21 December, the gulf was virtually unprotected. Blair wrongly accused Wilkes of not vectoring boats toward the gulf until after the Stingray’s contact report was received. In fact, two S-boats were on the way before the invasion force was reported, and Wilkes immediately directed other boats into the gulf.34 But it was a waste of assets to position so many of the boats to the east and south of Luzon, where there was little action. In addition, nine other boats were in the vicinity of Lingayen Gulf, most transiting to their areas or returning from initial patrol stations. They could have been ordered into the fray. Why some or all of these boats, with plenty of torpedoes, were not diverted into the Asiatic Fleet’s most important action of the first three weeks of the war is difficult to understand.

7. Unnecessary loss of matériel and men. Blair described as avoidable the loss of 233 torpedoes ashore when Cavite Navy Yard was bombed on 10 December, but most of those torpedoes likely would have been lost when Manila fell three weeks later. He also thought the failure to send the submarine tender Canopus (AS-9) south when Wilkes had the chance led unnecessarily to her eventual scuttling and the imprisonment of her fine crew.35 But Hart decided not to risk losing the ship in an attempt to escape south to Australia, instead retaining her in Manila to keep his submarines fighting as long as possible. While regrettable, it was not a major factor in the poor performance of the submarines in December 1941.

8. Failure to take immediate action to make a live test on the Mk 14 torpedo.36 There was not enough data yet from the boats after a few weeks of action to realize there may have been problems with the torpedoes. Wilkes and his staff were scrambling to control their boats while dodging bombs at Manila.37 It is difficult to imagine how they were supposed to make even a crude test in Manila Bay, as Blair suggested. While defective torpedoes were a major factor in the poor submarine performance, CSAF should not be blamed for not doing testing.

Analyzing the Conclusions

Blair is on target in four of his eight major errors of the submarine defense of the Philippines. The lack of initial deployment before the start of war, the failure to plan and execute a vigorous scheme to attack the invasion convoy at Lingayen Gulf, faulty peacetime training, and pre-patrol briefings that instilled skippers with caution were all important factors in the outcome of the campaign. His other arguments carry less weight. However, clearly Blair thought that unreliable torpedoes were a major factor. Had he stated his eighth error as “failure of Navy weapons development teams before the war to adequately test the Mk 14 torpedo and the Mk 6 magnetic exploder,” he would have had five valid major errors.

There are no answers to be found in Wilkes’ report to some uncomfortable questions that arose from Blair’s evaluation. Why was there no mass submarine deployment in advance of the commencement of hostilities? This might have yielded important strategic and operational effects. Why did CSAF not position several or all of the S-boats inside Lingayen Gulf? Why were more of the available submarines not vectored to attack the invasion convoy? These actions might have resulted in better performance in attacking the main invasion convoy, although with the defective torpedoes, it is unlikely they would have significantly altered the outcome. A hard-hitting, insightful self-assessment would have addressed these failures.

Both Wilkes and Blair failed to address one key issue: Were Hart’s submarines capable of leading an effective naval opposition to the invasion of the Philippines? Blair wrote that properly employed and operated U.S. submarines with reliable torpedoes may have been able to prevent the loss of the Philippines and Dutch East Indies.38

I believe that for a naval force composed mainly of submarines, supported by modest air power, staving off defeat was a long shot. There was even less chance the submarines would be successful as the campaign progressed and U.S. air power was destroyed, surface ships moved south, and a flawed operational plan for the defense of Lingayen Gulf unfolded. Even if the criticisms suggested by Blair and Wilkes had been remedied, it is doubtful that a plan relying primarily on submarines could have overcome the scheme of operations so deftly executed by highly trained Japanese forces spring-loaded for war.

The results of their performance in the defense of the Philippines were a crushing disappointment to the submariners, and changes clearly were necessary. Although the torpedo fiasco would not be fully resolved until mid-1943, the trajectory of submarine force performance began to trend upward from its nadir of the first four months of the war.

The submariners learned from their failures and put the lessons to use. In 1943 and 1944, they finally fulfilled the promise of a well-designed fighting platform, using proven tactics, employed in an effective operational scheme, supported by actionable intelligence, with reliable weapons and well-trained fighting crews. New boats outfitted with improved technology and experienced crews strangled the Japanese homeland through a devastating war of attrition against their merchant marine and the Imperial Japanese Navy. But they owed a debt to those Asiatic Fleet submariners who helped show them the way.

1. Ronald H. Spector, Eagle against the Sun: The American War with Japan (New York: Random House, 1985), 483. Quotes war correspondent Hanson Baldwin.

2. Clay Blair Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War against Japan (New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1975), 145.

3. John D. Alden and Craig R. McDonald, U.S. and Allied Submarine Successes in the Pacific and Far East During World War II, 4th ed. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2009), 27–29.

4. CAPT John E. Wilkes, USN, “War Activities Submarines, U.S. Asiatic Fleet December 1, 1941–April 1, 1942,” RG 38, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD (hereafter, NARA), 2.

5. James Leutze, A Different Kind of Victory: A Biography of Admiral Thomas C. Hart (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1981), 216–20.

6. ADM James Fife, USN (Ret.), The Reminiscences of James Fife, oral history interviews conducted by John T. Mason, Oral History Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York, 1962, 214–15, 225. See also Blair, Silent Victory, 130–32.

7. LT James W. Coe, USN, “Brief Summary of USS S-39 War Patrol Report,” 21 December 1941, RG 38, NARA, 1; and LT Charles L. Freeman, USN, “Report of USS Skipjack War Patrol, Period December 9, 1941 to January 14, 1942,” 25 January 1942, RG 38, NARA, 1–3, 14. Also Blair, Silent Victory, 143.

8. Wilkes, “War Activities Submarines,” 3–4, 61–62. For information on the Seawolf’s dud, see Blair, Silent Victory, 136.

9. Wilkes, 3–4, 61-62. Also see Blair, 138–41, for info on malfunctioning torpedoes.

10. Wilkes, 3–4, 61–62. Information on S-36’s communications problems is on page 8.

11. Carl LaVO, “Commanding Officer Breaking Down,” Naval History 6, no. 4 (Fall 1992) 29–34, describes the saga of the interaction between the Sailfish (SS-192) and Japanese destroyers off Vigan on 13 December and the skipper’s breakdown.

12. Blair, Silent Victory, 145–51. Also useful are war patrol reports from the participants Stingray, Permit (SS-178), Porpoise (SS-172), Saury (SS-189), Salmon (SS-182), S-38, S-40, and S-41, RG 38, NARA.

13. Fife, Reminiscences, 287–90. The action report was written almost completely by Wilkes’ chief of staff, James Fife. See also Blair, Silent Victory, 197–98.

14. Wilkes, “War Activities Submarines,” 48.

15. David C. Evans and Mark R. Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy 1887–1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 503, 505, 507, and 595 nr. 69. See also “Japanese Radar Equipment in WWII,” www.combinedfleet.com/radar.htm, for information regarding installation of surface-search radar on Japanese destroyers.

16. Wilkes, “War Activities Submarines,” 44–45.

17. Wilkes, 45.

18. Wilkes, 53. LCDRs Morton C. Mumma Jr. in the Sailfish and Raymond S. Lamb in the Stingray. The report noted that the skippers Wilkes relieved suffered from “nervous exhaustion or other physical defects or who may have shown temperamental inaptitude for the rigorous demands of submarine duty in wartime operations.”

19. Wilkes, 54–55.

20. Wilkes, 9, 35–37.

21. Wilkes, 58.

22. Blair, Silent Victory, 156.

23. Blair, 156.

24. Wilkes, “War Activities Submarines,” 61–62.

25. Blair, Silent Victory, 157.

26. Fife, Reminiscences, 212–13.

27. Blair, Silent Victory, 157–58.

28. Blair, 158.

29. Blair, 158.

30. Wilkes, “War Activities Submarines,” 4.

31. Blair, Silent Victory, 131.

32. Wilkes, “War Activities Submarines,” 9. See also participating boats’ war patrol reports, RG 38, NARA.

33. Blair, Silent Victory, 158–59.

34. LT Nicholas Lucker Jr., USN, “Report of War Patrol, USS S-40, Covering the Period December 19, 1941 to February 3, 1942, February 5, 1941 [sic],” Historic Naval Ships Association, 2, issuu.com/hnsa/docs/ss-145_s-40. Also see LCDR Eugene B. McKinney, USN, “USS Salmon, Report of Number One War Patrol, Period December 20, 1941 to February 13, 1942,” undated, RG 38, NARA, 1; LT Wreford G. Chapple, USN, “War Patrol, USS S-38, 30 January 1942,” RG 38, NARA, 5–6; and Blair, Silent Victory, 147.

35. Blair, Silent Victory, 159–60.

36. Blair, 160.

37. ADM Stuart S. Murray, USN (Ret.), Reminiscences of Admiral Stuart S. Murray, oral history interviews conducted by CDR Etta-Belle Kitchen, USN (Ret.), in 1972 (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute), 130.

38. Blair, Silent Victory, 20.