Beginning on 5 August 1964, in the immediate wake of the Gulf of Tonkin incident, U.S. attack aircraft carriers in the South China Sea began conducting sustained aerial operations against North Vietnam and communist forces in South Vietnam. For nearly the first three years of the effort, five of the dozen carriers that participated were the most recent so-called supercarriers, including the nuclear-powered USS Enterprise (CVAN-65). All were Pacific Fleet ships. The USS Forrestal (CVA-59), the first completed supercarrier, would be the first of those based in the Atlantic to conduct combat operations from Yankee Station off the coast of Vietnam.

The Initial Event

The Forrestal arrived at Yankee Station on 25 July 1967 and launched her first strikes at 0600 that day. The skipper of the Norfolk-based carrier, Captain John K. Beling, and his crew were determined to show the Pacific Fleet what they could do. The Forrestal rearmed that evening from the ammunition ship Diamond Head (AE-19). Over the next four days, the carrier’s aircraft flew more than 150 sorties over North Vietnam without losing a plane.

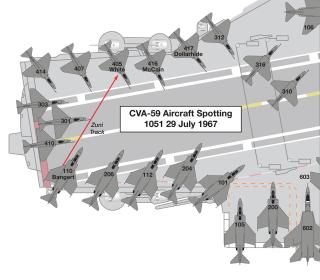

At 1050 on 29 July, the Forrestal was steaming through the placid waters of the South China Sea preparing to send her second strike of the day toward North Vietnam. More than 20 aircraft crowded the ship’s aft flight deck with barely walking room between them. Nearly 20 more were jostling for position on the remainder of the four-acre deck. With the aircraft fully fueled and armed, their engines were being spooled up, and pilots along with plane and deck crews were making last-minute checks for an 1100 launch. One minute later, the 5,400 sailors and airmen of the Forrestal began a fight for their lives and that of their ship.

Pilot Lieutenant Commander David Dollarhide was in one of the attack jets armed with two Korean War–vintage bombs. His A-4E Skyhawk #417 of Attack Squadron (VA) 46 was parked next to and forward of Lieutenant Commander John McCain’s Skyhawk. Dollarhide wrote in his diary:

Seven minutes before launch, I heard a muffled explosion above the noise of the engines and looked back to the right of my aircraft to see a mass of flames from my right wing going aft down through the other A-4s. There were several people in flames, rolling on the flight deck and running to put out the flames on their bodies.

An errant electrical charge had ignited the motor of a 5-inch Zuni rocket mounted on an F-4B Phantom II fighter. The rocket whooshed 100 feet across the deck, severing the arm of a crewman in its path, before striking and rupturing the external fuel tank of an A-4E Skyhawk attack bomber.

According to the Navy’s official report—the Manual of the Judge Advocate General Basic Final Investigative Report Concerning the Fire on Board the USS FORRESTAL (CVA-59): “A review of the voluminous material . . . establishes the central fact that a ZUNI rocket was inadvertently fired from an F-4 aircraft (#110) and struck the external fuel tank of an A-4 aircraft (#405).” Lieutenant Commander Jim Bangert of Fighter Squadron (VF) 11 was the pilot of F-4 #110. Lieutenant Commander Fred White, who died in the fire, was the pilot of A-4 #405, just aft of McCain’s #416, both of VA-46.

Jet Fuel, Fire, and Bombs

As 400 gallons of jet fuel was both blasted and spilled from the fuel tank to the deck, it ignited and spread beneath other aircraft. Dollarhide wrote: “I saw one of our Plane Captains . . . reeling backward just out of the fire, his entire body charred and still burning. His left arm was almost completely severed and he was trying to hold it on.”

Either because of the impact, the explosion, or an electrical short caused by the incident, at least one of the two vintage 1,000-pound bombs under the wing of White’s bomber fell to the deck. Witnesses reported seeing the insides of one of them, which had split open, burning with a white-heat ferocity.

Just feet from the epicenter of the fire, Dollarhide recalled climbing out of his Skyhawk:

I leaped out the left side because of the fire on the right. My feet caught on the canopy rail and I did a three quarter twist, landing on my right hip. (My right hip and elbow were broken.) I couldn’t get up and rolled on the deck for a few seconds till a kid came over and helped me up.

As those amid the spreading flames tried to escape, others manned fire hoses and extinguishers to battle the flames. Fifty-four seconds after the fire broke out, Chief Aviation Boatswain’s Mate Gerald W. Farrier, the head of the firefighting crew, arrived at the scene and immediately began battling the blaze around the cracked bomb with a handheld fire extinguisher. About 20 seconds later, the first of the hose crews arrived, playing saltwater on the forward boundary of the fire.

Dollarhide wrote that he “rolled over and looked back to see everything from the plane next to mine on down [the deck] engulfed in fire. I wondered if the pilot [John McCain] had gotten out or if he was leaning forward in the cockpit.”

Slightly more than 90 seconds into the fire, the bomb exploded. Aviation Boatswain’s Mate Third Class Gary L. Shaver remembered:

There was a 1,000-pound bomb laying on the deck surrounded by burning fuel. I emptied the extinguisher to no avail. Several feet away from me was . . . Chief Farrier who also had an extinguisher and was applying it right on the bomb. Suddenly there was an explosion. Chief Farrier disappeared. I felt like I was going to come apart as the bomb’s concussion and shrapnel hit me. I was blown into the air, out of my shoes and helmet, and struck by shrapnel in the left shoulder, stomach, arms, and head.

The two fire crews first on the scene were decimated.

Nine seconds later, a second bomb exploded with even more ferocity. Bodies and debris were hurled nearly a thousand feet forward to the bow of the ship.

More Extensive Destruction

Within the first five minutes of the disaster, the aft end of the 1,039-foot ship was rocked by seven more major explosions of 1,000-pound bombs. Minor explosions were too numerous to count. The fires were fed by 40,000 gallons of highly volatile jet fuel spilling from tanks and fuel cells ripped by blasts and shrapnel.

The explosions smashed holes in the nearly two-inch-thick armor flight deck. Flaming and unburned fuel, water, and fire-retardant foam cascaded into the compartments below—primarily crew berthing areas.

Fighting the fires belowdecks, given the confined spaces, lack of light, thick black smoke, and concentrated toxic fumes, was even more dangerous than battling the flight-deck blaze. While the fire on the flight deck was contained within an hour, those below raged until 0400 the next day.

As a result of the fires and explosions, 134 sailors and airmen died, and 161 others were seriously wounded. Many more men were injured but did not report their wounds because they were less severe. Of those who died, only 28 had been on the flight deck; 50 died while asleep in their racks.

Twenty-one of the 73 aircraft on board were destroyed, with another 40 damaged. Repairing the carrier cost $72 million; destroyed aircraft accounted for another $44.5 million, with another $10 million to repair damaged aircraft. Ordnance lost was valued at $1.95 million, and supplies and equipment destroyed were put at $3.15 million.

Investigation and Conclusions

On 1 August, the Forrestal docked at Naval Air Station Cubi Point’s Leyte Pier in the Philippines’ Subic Bay. Amid the continuing process of searching for and recovering remains of missing shipmates, emergency repairs were begun to ensure a safe ocean passage. This included patching her flight deck so she could launch and recover aircraft if the need arose.

The damage was substantial. Roughly the aft 200 feet of the ship from port to starboard at the hangar- and flight-deck levels, including at least a dozen berthing compartments aft, received the heaviest damage. All four gun mounts were destroyed. But damage extended as far as frame 176, nearly 100 feet farther forward. Further damage stretched from the mainmast 80 feet above the highest level of the island to below the waterline in the port rudder.

On 2 August, the accident’s investigation board convened on board ship. It interviewed the crew; examined aircraft, electrical, and safety systems; studied firefighting apparatus and training; and conducted a static firing of a Zuni rocket from an F-4B. Other tests, specifically on the thin-skinned bombs, were scheduled to take place stateside. The panel continued to meet during the ship’s one-month transit back to home port.

The board focused on the Zuni rocket and its LAU-10 launching pod. Witnesses generally agreed that the rocket’s impact with White’s aircraft started the fire and that the blaze was containable and they had a chance to knock it down until that first bomb went off.

The Navy’s final report found shortcomings in the Zuni launching pod. Attachment cords between the pod and its mounting rail on the aircraft, called “pigtails,” carried the electrical firing charge from a switch on the pilot’s control stick to the rocket’s igniter. Pins on the pigtail could be bent, causing a short circuit.

Further, there were two separate safety procedures to prevent an inadvertent firing of a Zuni. One was that the pigtails were not to be plugged in until immediately before the aircraft’s launching. With the high tempo of flight-deck operations, the delayed connection of pigtails slowed launches to the degree that it caused conflicts with the launching of aircraft for one mission and the recovery of those from the previous one. Veterans of the experienced Pacific-based carriers passed this information to the newly arrived Forrestal squadrons. Their ships’ safety committees chose to bypass this safety procedure because there was a more significant safety device that was highly effective.

That device—the TER-pin (the rocket launcher was attached to the triple ejector rack [TER])—was essentially a safety pin that mechanically and electrically prevented the launch of a rocket. Standard procedure was for the pin in the TER to be pulled only immediately before launch. However, in some instances, crews pulled the pins before the aircraft got to the catapult, again in the interest of getting aircraft off the deck as soon as possible.

The Navy investigation determined that the rocket fired when the pilot of the F-4B carrying the Zuni switched power sources. The jets on board the Forrestal required an external starter to get their turbines to turn over. Once one of the engines in the twin-engine Phantom II was at a certain level, the pilot would switch from the external source to the internal source powered by the running engine. When the pilot switched power sources, there was a brief spike of electrical energy.

Alone, the spike would not have launched a Zuni. However, with the pigtail connected, the electricity had a route to the rocket. With the safety pin pulled, the Zuni was electrically and mechanically free to be fired. While that was determined to be the cause of the rocket’s firing, and its subsequent impact with another aircraft’s fuel tank was the cause of the fire, the events need not have been the cause of many deaths.

Old Bombs and Firefighting

For the 1100 mission on 29 July, 80 bombs totaling 24½ tons of high explosives were on board 15 attack aircraft. Sixteen old AN/M65A1 1,000-pound bombs accounted for eight of the tons. The seven of them that exploded did so in a catastrophic “high order” fashion. The nine others were listed as missing or jettisoned.

According to the investigation report, the old bombs, which caused so much death and destruction, were manufactured in 1953, filled with Composition B explosive, and had been stored “for years” on Okinawa or Guam. Unlike modern explosives, “Comp B” became unstable with age, especially in hot, humid storage conditions. At the least, these weapons were 14 years old and had been stored in the open in the hot, humid climate of the islands.

The M65s were “thin skinned,” the outer casings just thick enough to hold the explosives and their shape. The more modern Mk 80–series bombs on board the Forrestal had thicker skins, which provided significantly more insulation for the explosive from heat and shock. Of the 64 “modern” bombs prepared for launch, only two exploded during the fire at a “high order” and two at “low order.” The rest burned, melted, or were jettisoned.

Experts estimated that the firefighters needed only three minutes to contain the fire. The first of the M65s blew up 94 seconds after the blaze started. None of the four modern bombs detonated until more than five minutes had elapsed. The issue of the old bombs was not significantly covered in the investigation’s conclusions.

The report also addressed firefighting issues. While praising the crew for its courage and tenacity in battling the blazes, the investigation concluded that firefighting should be left to professionals. The most effective means of fighting a fuel fire on board ship is with foam, which blankets the flames and fuel source, effectively smothering the fire. Water serves only as a cooling agent. It tends to spread the fire around, as the fuel floats on top of the water.

The first explosion decimated the Forrestal’s two main firefighting crews, taking with them the initial foam hoses on the scene. The water used by later crews spread the fire rather than put it out.

Fallout and Return Home

Although the report cited the errors of safety checks on the rocket, it found no one on board the ship directly responsible for the fire and subsequent explosions.

Changes were made after the fire. Zuni safety procedures were reevaluated and strengthened. Old bombs were removed from the munitions pipeline, and newly manufactured bombs were given a plastic-like coating as a further insulation against fire. Attendance at firefighting school, at a facility named after Chief Farrier, became mandatory for sailors.

On 11 August, the Forrestal set out from Subic Bay westward bound on the long journey around the Cape of Good Hope to her home port. On her way, she steamed back to the war zone, where the crew dropped a wreath in memory of their lost shipmates. On 12 September, she arrived at Naval Station Mayport, Florida, where she disembarked aircraft and crews of Florida-based squadrons. The carrier departed in the next day’s early afternoon and arrived at Norfolk on 14 September, docking at Pier 12 to the cheering of more than 3,000 family members and friends.

Lieutenant Commander McCain Is Blameless

John S. McCain III, the late Arizona senator, falsely has been accused of accidently starting the Forrestal fire by showing off with a “wet start” of his A-4E Skyhawk, which launched an F-4B’s destructive Zuni missile. A wet start happens when the igniters in the engine do not energize or fire before the atomized fuel enters the hot section of the engine. It can be caused by the start procedure getting out of sequence, a malfunction in one of the components, or, in some cases, if the person starting the engine does not follow the correct sequence by turning on the engine fuel master switch before hitting the igniter switch. Once started, the pooled fuel shoots out the tail in an impressive flame.

Allegations of then-Lieutenant Commander McCain having any culpability for the fire are unequivocally false. His A-4E was spotted on the port quarter with its tail hanging over the deck pointed at the ocean. The F-4B that launched the Zuni was spotted on the starboard quarter, also with its tail pointed toward the ocean on that side. Essentially their noses were pointed at each other. There is physically no way a flame from McCain’s A-4’s engine could have reached around 180 degrees and crossed 100 feet of flight deck to ignite the F-4’s Zuni.

Sources:

This articles relies primarily on the author’s interviews with the quoted individuals and the Manual of the Judge Advocate General Basic Final Investigative Report Concerning the Fire on Board the USS FORRESTAL (CVA-59).