H-Hour of D-day, 21 May 1982, for British land operations to start the recapture of East Falkland Island from the Argentineans was set for the darkness of 0630 hours Greenwich Mean Time. The South Atlantic campaign, Operation Corporate—the objective of which the amphibious landing was a part—was to defeat the sizable Argentine Army and Air Force contingent occupying the Falkland Islands.

Prelude

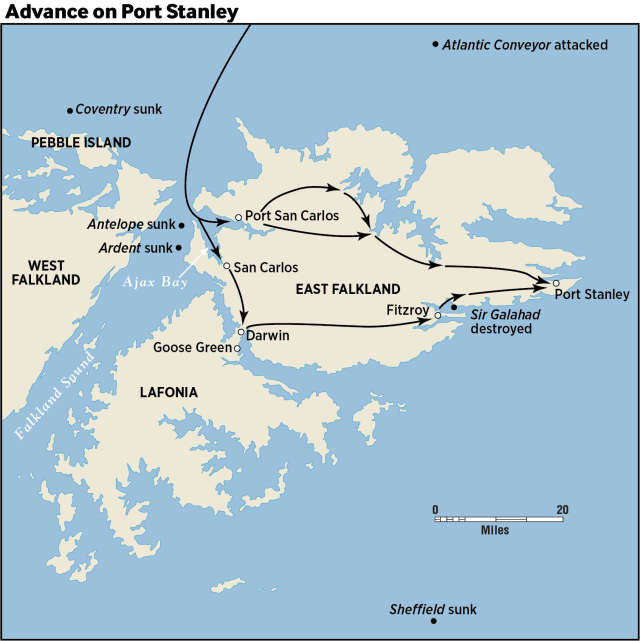

The British Landing Platform Docks (LPDs) HMS Fearless and Intrepid reached their assigned anchorages at 0345 and 0337 respectively and began to disgorge their Landing Craft Utility (LCUs) and unload davit-slung Landing Craft Vehicle and Personnel (LCVPs). Each LPD carried four LCUs and four LCVPs. Once loaded with Royal Marine commandos and Army paratroopers, the landing craft made for their color-coded landing beaches. Upon reaching the shore, the first combatants waded through the salt water to assembly areas and deployed. The landing was unopposed—and the Royal Navy was about to turn its attention to a major armed ground thrust eastward to eject the Argentineans from the island.

The invasion of East Falkland Island was not the first action of British troops on the island, but it was the grand finale to Operation Corporate. With the sinking of the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano, the Royal Navy, which included 3 Royal Marine Commando Brigade, had been engaged in significant sparring with its foe since 2 May. Now it was time for the land elements to carry the war to the enemy—but not without what turned out to be essential support involving carefully defined Royal Navy roles.

The land campaign involved four major Royal Navy contributions: naval gunfire support, waterborne logistic assistance, vertical movement participation, and higher-echelon medical care. These areas were not exclusive, however, since the campaign was very much an integrated armed force effort. Each service complemented its appropriate counterpart in some way with functions being distributed based on need and opportunity.

Naval Gunfire

Shortly before the main body of commandos and paratroopers set foot on East Falkland Island soil, the 4.5-inch-gunned destroyer HMS Glamorgan delivered diversionary fire on the Berkeley Sound beaches located on the east end of the island. The intent of the action was to make the Argentine forces believe the main British landing attempt would be made in the vicinity of those beaches, a logical place close to the town of Stanley, the major British objective.

Close to the various landing times, the similarly armed HMS Antrim stood by to give supporting fire to Special Boat Squadron Marines in routing a small group of Argentineans occupying positions on Fannings Head. Just previously, the Antrim naval gunfire observer had directed the fire of 20 rounds of variable time fused ammunition above the foes’ heads.

Once established on shore, the five-battalion 3Royal Marine Commando Brigade began to assemble sufficient supplies to advance east toward Stanley. Unfortunately, the British high command had little understanding of the need to set up a firm logistics base and wanted action without delay. The result was that Royal Marine Brigadier Julian Thompson, the brigade commander, dispatched 2nd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment (2 Para) to capture the settlement of Goose Green from the Argentine Air Force elements stationed there. The taking of Goose Green and its airstrip, however, was of no strategic importance and a significant diversion of logistic efforts to support the British eastward advance.

Para’s attack on 28–29 May was to be supported by three 105mm light guns from 29 Commando Regiment Royal Artillery and the 4.5-inch gun of the frigate HMS Arrow. This proved to be the first time that a Royal Navy ship and ground artillery fire were integrated in providing fire support to the land force in the campaign. In addition to employing the gunfire, because the attack was to be made at night, the Arrow also would fire star shells to illuminate the battlefield. This was to be conducted against Argentine positions at Boca House, which was located close to the shore line of Falkland Sound, and Burnside House, more inland, from about 0230 hours until dawn. The Arrow, however, had only a small number of illuminating rounds, which meant they had to be used sparingly. Using a combination of those rounds and high-explosive ammunition from its cannon, the Arrow stayed on the gun line until dawn, a time well beyond her allotted tenure in a fire support role.

Later harassing gunfire by the frigates HMS Avenger and Alacrity, along with the Glamorgan —in support of 3 Royal Marine Commando Brigade’s battalion-size 42 Commando on Mount Kent—helped the commandos secure the vital piece of terrain on 30 May. Commando elements, including three light 105mm artillery field pieces, were flown in to the mountain by three Navy Sea King helicopters and the sole available Royal Air Force Chinook heavy-lift helicopter. Another example of interservice cooperation, which was so prevalent in the entire campaign, thus was demonstrated again.

While the position on Mount Kent was consolidated and the 105mm cannon took up firing positions, the ships providing the gunfire moved on to their next task. Along the northeast shore of North Falkland Island, a naval gunfire support box—a seaward area five miles long and a thousand yards wide—was to be swept for mines in Berkeley Sound by 12 June. The Arrow was to be there and “on-call” to employ her 4.5-inch gun to support night ground attacks, which the ship subsequently executed.

Along the southern gun line, other warships had been active since 6 June, when the army’s 5 Infantry Brigade was moved to the vicinity of Bluff Cove. From then until the Argentine land forces surrendered on 14 June, ships including the Avenger, HMS Yarmouth, and Glamorgan pounded enemy positions as the ground forces’ night attacks went forward. In combination with Arrow in the north, for example, those vessels firing from the south during the night of 11–12 June expended 788 rounds of 4.5-inch ammunition. The results were rather meager, however, with only a fuel dump, a 155mm gun, and some troop positions being accounted for. The principal impact, and a highly desired one nevertheless, was to keep the foes’ heads down, their anxiety level high, and their nights sleepless.

In assessing the effectiveness of the 4.5-inch naval guns as well as the commandos’ light artillery pieces during the campaign, Brigadier Thompson determined that they were incapable of destroying hard or static targets. The psychological effect of a constant barrage of flying metal over time, however, played well to the detriment of much of the Argentine force, which consisted of many young conscripts who for the first time in their lives were being exposed to a deadly combat environment.

Waterborne Support

While the the 4.5-inch guns of the Royal Navy’s combat ships were pounding the Argentines, the Navy also was providing essential waterborne support to the land forces engaged on East Falkland Island. Sailing throughout and around a myriad of bays and inlets, past small islands, and stopping at undefended beaches and Falkland settlements, the ships became the life’s blood of ground operations. Where the variable and adverse weather often curtailed supply by helicopter, various-sized vessels from landing craft to Landing Ships Logistic (LSLs) executed the requirement to serve the land force once it had come ashore in San Carlos Water.

The role of the Royal Navy in providing waterborne support to the ground forces was dictated by the nature of the terrain and a primitive overland communications system as well as the weather. There were no navigable rivers on the island, but instead large rock-strewn streambeds. High dry ground, where it existed, was hardly trafficable by wheeled vehicles. Mushy peat bogs restricted any kind of overland vehicular movement. Paved surfaces outside Stanley were all but nonexistent. Inclement weather, as the southern hemisphere winter approached, turned already rutted trails, tracks, and paths into sticky mud, making it impossible to move heavy loads over land. All these factors influenced how the land forces were to be supported, thereby making waterborne activity vital to providing adequate logistic and personnel support.

Supporting movement by water was roughly divided into two categories: transport of troops to advanced positions, and delivery of supplies, equipment, and expendables to the two Forward Brigade Maintenance Areas (FBMAs). Of the two categories, the logistic operation became the more prominent and critical, since moving large masses of equipment and stores could be done only by water.

Thus, on 21 May, as the Navy’s LCUs and LCVPs brought men, equipment, and supplies ashore, a Beach Support Area (BSA) was established on the shore of San Carlos Water. While commandos and parachutists regained their land legs and dried out their salt-encrusted footwear, the commando brigade logisticians built up a supply base to be serviced from the sea by the Royal Navy. The process of establishing a viable logistic base was a slow one since there were no sophisticated docking facilities available in San Carlos Water. Unloading from ships had to be done by the landing craft aided by ramp support pontoons or floating causeways called Mexeflotes.

From 21 to 27 May, efforts were concentrated on providing sufficient supplies to make it possible for the ground troops to advance eastward and defeat the Argentine forces concentrated around Stanley. Except for intelligence forays by Royal Marine Special Forces at the time, there was no significant troop movement in that direction. At first, Thompson spent the time planning the advance of his men primarily utilizing the heavy-lift Chinook helicopters that were expected to arrive soon.

On 25 May, however, the Ship Taken Up From the Trade (STUFT) Atlantic Conveyor carrying three of the four Chinooks was sunk, and Thompson had to radically change his plans. All the while, the overall commander of the combat task force and high-ranking government authorities back in the United Kingdom were clamoring, regardless of the status of supplies to support an advance, to get moving east. At the same time, as a result Thompson was compelled to launch the attack on the substantial settlement of Goose Green.

The requirement to use watercraft to support the eastward land movement had not yet arrived, but the ground advance by foot troops had been set in motion. The Parachute Regiment’s 3rd Battalion and 42 Commando began their “yomp” afoot east towards Mount Kent, where they were to find helicopter delivered compatriots and their light artillery pieces already in place.

It was now time for the Navy’s Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) LSLs to come into play in moving ammunition, food, and equipment forward. On the night of 1–2 June, for example, the LSL Sir Percivale sailed into Teale Inlet with 300 tons of stores and 600 troops for the commando brigade. With it went two LCUs to unload the supplies at the newly established FBMA. The area around Teale Inlet on the north coast of East Falkland Island was by then firmly under the control of 45 Commando. From there supplies would be sent forward principally by helicopter. When fully operational the FBMA supported the entire commando brigade until the end of the campaign. The Sir Percivale, Sir Geraint, and Sir Galahad between them made five trips to the location.

Although placing the FBMA in Teale Inlet was considered a risk, it was never attacked by Argentine aircraft—a situation that did not obtain around Fitzroy and Bluff Cove at Port Pleasant on the south coast of East Falkland Island.

On 8 June two waves of Argentine Skyhawk aircraft attacked the Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram in the waters at Port Pleasant. The Sir Galahad was partly unloaded of Welsh Guardsmen and Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) personnel when the LSL was bombed, resulting in high casualties among those on board. The ship was so badly damaged that she later was sunk to become a water gravesite. The Sir Tristram, transporting supplies and equipment, also received a serious hit and was severely damaged but remained afloat although largely unserviceable. She later was returned to Great Britain and repaired.

While the LSLs served primarily to move supplies and equipment about, the eight LCUs were employed to move both personnel as well as supplies from place to place and ship to shore. LCVPs, on the other hand, with limited carrying capacity were used principally to transport personnel. Manned by Royal Marines, who were part of the LPD’s ship complement and “drove” the boats, the overworked craft often were sailed under unfavorable weather conditions and frequently placed at risk from hostile aerial attack.

The LPDs were considered capital ships—and, if sunk by the Argentineans, would have resulted in not only adverse military consequences, but also in possible defeatist political action back in the United Kingdom. The ships therefore were not permitted to be put at risk wherever possible and, after the initial landing in San Carlos Water, were kept from enemy action close to the battle front. Nevertheless, in moving troops of 5 Infantry Brigade forward, the Intrepid carried Welsh Guardsmen forward along the south coast of East Falkland Island to rendezvous with her LCUs around Lively Island prior to the troops’ deployment for the advance on Stanley.

The waterborne effort to support the ground troops, although briefly stunted by the grievous aerial attack of 8 June, was an overwhelming success. But it was only a part of the transportation activity required to support, logistically and personnel-wise, the overland attack on Argentine forces on East Falkland Island. The needed complement was the helicopter.

Vertical Movement Operations

With an adequate road network nonexistent on East Falkland Island and no significant internal waterway over which to move men and matériel about, primary resort had to be made to the helicopter lift of personnel, weapons, equipment, ammunition, and supplies once ships and other watercraft had brought them ashore. To do so there were four military operators providing the necessary airlift. The Royal Air Force (RAF) deployed one Chinook heavy-lift helicopter. The Royal Marines and the Army flew light helicopters which evacuated casualties and transported limited supplies along with small groups of combatants. The major role was played by Royal Navy with its Sea King and Wessex helicopters, which carried the bulk of the aerial movement load.

It had not been planned that way, however. The RAF was to contribute four Chinook heavy-lift aircraft as its contribution to the effort. When the Atlantic Conveyor was sunk on 25 May, three of the four onboard RAF helicopters, along with six Wessex helicopters, were destroyed. The loss dramatically changed and compromised previous plans to support the overland effort’s heavy-lift requirement.

The Sea King in several configurations did the yeoman work when it came to providing significant needed carrying capacity. The aircraft carriers HMS Hermes and Invincible each carried an antisubmarine helicopter squadron, the Naval Air Squadrons (NAS) 826 and 820: the carriers each transporting nine Sea Kings. Also on board the Hermes was NAS 846 with nine Sea King helicopters fitted out specially to carry combat-loaded personnel. Three more Sea Kings were transported on the Fearless. Flights A and C of NAS 824 arrived south on board the Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) ships Olmeda and Fort Grange respectively. An additional Sea King squadron, NAS 825, was formed with ten helicopters for the specific purpose of providing additional troop transport capacity. It was embarked on the STUFT Atlantic Causeway, and the helicopters started landing at San Carlos settlement on 27 May.

NAS 820 and 826 spent most of their time on antisubmarine missions but, in anticipation of the ground advance, were engaged in airlift activities from 3 to 6 June.

NAS 824’s two flights were heavily employed in Helicopter Delivery Service (HDS) of utility missions in San Carlos Water during the same period. The bulk of the direct support of the ground-force action by Sea Kings thereby came to rest on those helicopters of NAS 825 and 846.

NAS 825 Sea Kings performed a variety of HDS missions, the most spectacular being by four Sea Kings assisting in rescue and recovery operations on 8 and 9 June from the Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram. It was instrumental on 2 June in moving Argentine prisoners of war from Goose Green, and when the 5 Infantry Brigade landed it performed numerous HDS operations in support of it. The squadron also helped move an artillery battery to Teale Inlet and continued to fly resupply and troop transfer missions until 14 June. In two weeks of intense activity, it expended 1,700 flying hours, each helicopter normally carrying 16 fully loaded combatants and flying nine hours.

NAS 846 likewise was extensively multi-tasked. On the landing’s first day, each Sea King flew nine and half hours, disembarking 910,000 pounds of stores/supplies and equipment plus some 520 troops. In the next few days it transferred supplies for 2 Para preparing to attack Goose Green settlement. On 27 May, as it had squadron pilots equipped with passive night goggles (PNG), a Sea King moved a half battery of 105mm guns and ammunition to support the Goose Green attack and also transport stores and equipment to Mount Kent and Mount Challenger. In spite of bad weather, Sea Kings flew equipment to Teale Inlet and guns to Estancia House. A two-artillery battery and Rapier anti-aircraft element were flown to Teale Inlet on 5 June. PNGs enabled much flying to be done at night, but by 8 June the number of those tasks decreased to allow for more daylight flying. That included having a Sea King performing rescue work at Port Pleasant with the Sir Galahad.

By 10 June, the squadron was operating out of the Forward Operating Base (FOB) at Teale Inlet and beginning to fly missions in support of both the commando and army infantry brigades. The next day it transported 2 Para from Fitzroy to Bluff Peak in preparation for the final land push on Stanley. Now working in support of the ground artillery and its great demand for ammunition, the Sea Kings spent time delivering 105mm rounds on pallets to gun positions. On 13 June, for what appears to be the first time, a NAS helicopter was fired on by an Argentine aircraft. All in all, in the entire Operation Corporate campaign, the squadron compiled a remarkable record, with the helicopters flying 3107 hours; its pilots being in the cockpit 4,563 hours; and the number of sorties flown at 1,818, of which 736 were at night.

The Wessex helicopter in several configurations was employed to carry lighter loads than its larger Sea King brothers. Three squadrons of Wessex helicopters, NAS 845, 847, and 848, were specially formed for employment in the campaign. NAS 845 initially consisted of 18 helicopters, but when it arrived at Port San Carlos settlement the number of aircraft in its five flights was reduced to 12 in number. NAS 847, in two flights, deployed 12 helicopters each on the RFA ship Engadine and STUFT Atlantic Causeway, its first helicopters flying ashore to the FOB at Port San Carlos settlement on 1 June. NAS 848 was formed with 12 Wessex, six of which were lost on the Atlantic Conveyor when the ship was attacked. Divided into four flights, “A”, “B”, “C”, and “D,” only its “B” flight participated in airlift operations during the East Falkland Island combat phase of fighting.

The various lettered flights of the three Wessex NAS, on arrival, were quickly put to work. They flew all over the island performing a number of different functions. Like the Sea Kings, with which they worked seamlessly, the NAS transported troops and Argentine prisoners of war, carried expendables including ammunition and food, performed casualty evacuations, moved cargo and personnel between ships, deployed Special Forces and survey parties, and flew members of the press.

Flying in all kinds of weather, much of it deplorable, the helicopter crews and their aircraft maintenance personnel hardly paused in their work. The availability rate of the helicopters was also incredible, with a high percentage always being serviceable—a tribute to unsung heroes in support roles. The Navy’s helicopter contribution in support of land operations became a major and obvious highlight in bringing the campaign to a successful conclusion.

Higher-Echelon Medical Care

Helicopters also played a critical role in the medical treatment both of British and Argentine wounded personnel. All helicopters were potential transporters of casualties, down to the very smallest ones. The Navy’s light Wasp helicopter, for example, flying off the small ambulance ships, was essential in moving casualties and medical stores about offshore and to and from the Uganda, the ocean liner converted into a hospital ship.

Of the four support functions performed by the Royal Navy in the campaign, perhaps the most closely integrated one was the medical treatment given to wounded men after they had been evacuated from the front line to brigade aid stations and then to the surgical dressing station at Ajax Bay or the hospital ship Uganda and her supporting ambulance vessels.

Especially at the forward areas and at Ajax Bay, the cooperation was close. Navy surgeons from medical surgical support teams worked side by side with Royal Army Medical Corps doctors and medical corpsmen from the Parachute Clearing Troop, 16 Field Ambulance and 2, 5, 6, Royal Army Field Surgical Teams in performing essential surgeries and preparing the wounded for transportation to the Uganda or the three smaller converted medical ambulance/hospital vessels, the Herald, Hecla, and Hydra.

The higher-echelon medical effort on land was directed primarily by Surgeon Commander Rick Jolly, Royal Navy, who also commanded the Commando Logistic Regiment’s Medical Squadron. The squadron consisted of 1 and 3 Dressing Stations, an administration troop, and two attached Royal Navy Surgical Support Teams. When 5 Infantry Brigade landed, it brought additional Navy medical personnel with it, along with the three RAMC Field Surgical Teams.

Those who were wounded but in stable condition, both British and Argentine, were evacuated from regimental (battalion and commando) aid posts (RAPs) and quickly transported to the Medical Squadron Main Dressing Station at Ajax Bay, then on to the Uganda or the smaller hospital ships. Those who were critically wounded often were operated on at the BMA at Fitzroy or Teale Inlet before being moved to the facility at Ajax Bay or even to the Uganda.

Results from medical treatment facilities were impressive. More than 1,000 casualties (British and Argentine) were treated at the three facilities: 700-plus at Ajax Bay and 300 between the RAPs in the BMAs at Fitzroy and Teale. Two hundred and two major surgical operations were performed at Ajax Bay alone, with 108 additional such procedures conducted between RAPs at Teale and Fitzroy and on board the Uganda. Most impressive was that only three died of wounds after reaching a battlefield medical facility, and those expired on board the Uganda.

Conclusion/Summary

The Royal Navy’s directed support of land operations has received little attention within the context of the diplomatic and military campaign to reclaim the Falkland Islands. But without that support, the successful defeat of a large Argentine military contingent on East Falkland Island would not have been possible. While there were other operations, such as those on South Georgia Island and Pebble Island off West Falkland Island, none approached the magnitude of effort and commitment that those on East Falkland Island required.

The Royal Navy’s overall participation in Operation Corporate to recover the Falkland Islands was closely integrated with efforts from all the British armed services. The defeat of the Argentine ground forces on East Falkland Island was a prime example of such integration. But in four areas of the land campaign, the Navy’s efforts were salient even if not exclusive. The Navy played the important role of providing fire support with its combat ships’ 4.5-inch guns in cooperation with ground-based artillery. In delivering second-echelon and above medical support, its participation was critical. It alone managed waterborne transportation requirements in transporting supplies and personnel forward. And, except for one Royal Air Force helicopter, the major vertical movement support furnishing troops and matériel was in the Royal Navy’s domain.

When the Navy placed the commandos and paratroopers on the beaches of San Carlos Water in the early hours of 21 May 1982, the assumption was that ejecting the Argentine armed forces from East Falkland Island would be accomplished in a matter of a few days. What was not realized was that all the pieces required to make that assumption a reality would not fall neatly into place to make Operation Corporate a success. While the United Kingdom ultimately was successful, it took the Royal Navy’s dedicated support of the land forces to provide the critical pieces needed to achieve the desired result.

1. Raymond E. Bell Jr., A Close Run Thing (Washington DC: Unclassified Government Project Publication, 1985).

2. Roy Braybrook, Battle for the Falklands (3): Air Forces (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 1982).

3. Rodney A. Burden et al., Falklands: The Air War (London: Arms and Armour, 1986).

4. Michael Clapp and Ewen Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands (London: Leo Cooper, 1996).

5. Paul Eddy and Magnus Linklater, War in the Falklands (New York: Harper & Row, 1982).

6. Adrian English, Battle for the Falklands (2): Naval Forces (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 1982).

7. Jeffrey Ethell and Alfred Price, Air War South Atlantic (New York: Macmillan, 1983).

8. William Fowler, Battle for the Falklands (1): Land Forces (Oxford, UK: Osprey, 1982).

9. John Frost, 2 Para Falklands (London: Sphere Books, 1983).

10. John Laffin, Fight for the Falklands (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1982).