In March of 1982, I had been selected for promotion to commander, and as a temporary appointment I was leading a study into the complement of a new class of warships (the Type 23) and frequently visiting the historic Admiralty buildings where the Royal Navy’s personnel departments were housed. There of an evening I often drank a glass or two of sherry with another officer who shared my interest in South America. He had visited the Falkland Islands in a frigate and married an Anglo-Argentine woman; I had visited the Argentine twice in ships, and in 1971 I had led an expedition, by Land Rover, from Valparaíso, Chile, via Puerto Montt across the Andes to Buenos Aires. We both spoke Spanish, and I had many friends in that beautiful country.

Quite improperly, we had put ourselves on the delivery indictor group for signals about the growing crisis in the South Atlantic, and no one thought it strange to deliver highly classified messages—for example, from Captain Nick Barker in the Antarctic patrol ship HMS Endurance—to two middle-rank officers in the dim attics of the Admiralty. There we read and analyzed the signals avidly. It was clear to us that something quite extraordinary was happening on South Georgia—and that an Argentine invasion of the Falklands seemed to be obvious and inevitable.

We were unaware that, across the road in the main building of the Ministry of Defence (MoD), there was no similar appreciation of the intelligence. After the war I would read the report by Lord Franks, who had been commissioned by the government to enquire into what prior foreshadowing there had been of the looming conflict. Franks concluded that the British government had had no warning of the decision by the junta in Buenos Aires to invade the islands and that “the invasion of the Falkland Islands on 2 April could not have been foreseen.” I would be flabbergasted to read this.1

However, on the evening of Thursday, 31 March, I was not surprised to be detailed to join the Naval Emergency Advisory Group on the following Monday morning. I turned over the findings of the study I had been working on to the typing pool, expecting to sign it the next week and hand it in; I never saw that report again.

Cold Travel to a Hot Location

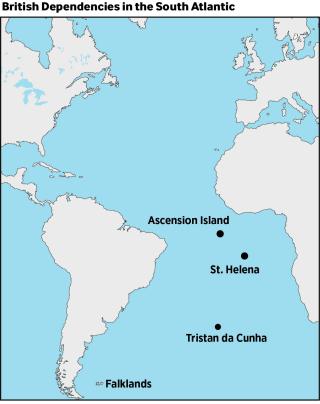

By the time that I arrived home in Devon, new orders reached me over the telephone: I was to be prepared to travel overseas. The speaker couldn’t tell me on an open line where nor what the task was, but I was to be prepared to be very cold while traveling and to arrive somewhere very warm. That sounded to me like a flight at high level in a C-130 Hercules transport to somewhere near the equator. A quick look at the atlas, using my forked fingers as dividers to measure off the distances, gave me a clue, and on Friday afternoon I visited the local library at Kingsbridge to glean what I could about my probable destination. There were three lines in a very large gazetteer about Ascension Island, and I duly went home to pack my tropical white uniform.

I distinctly remember on Saturday morning listening to the BBC and the debate in the House of Commons, which had been specially recalled. The government minister who was speaking knew less than I did from my reading of the signals a few days before, and he appeared unaware of the difference in time zones between London and the Falklands. Later that day, a car collected me and I was driven to Northwood, where I was taken into “the hole,” the underground headquarters, to meet the Commander-in-Chief, Fleet, Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse, in the cramped room that would be his in the event of a nuclear war.

Sir John said, “Ah, Peter, you’re going out to Ascension Island.”

“Yes, sir,” I replied, leaning forward to catch his softly spoken words.

“I want you to go there and make things work,” he said, looking hard at me, while I waited for him to say more, wondering what words of advice there were to follow. Instead, after a moment, he nicked his head at me, and I realized that that was my briefing.

“Aye, aye, sir!” I replied. Much later, when I became the Royal Navy’s Head of Defence Studies, I would look back on that exchange of words as a fine example of Auftragstaktik—that is, mission-command tactics focused on outcome rather than means.

‘The Most Hostile Environment’

The original signaled requirement was unambitious, stating only that the probability existed of passing small quantities of urgently needed air-portable freight through a temporary airhead on Ascension. Retired U.S. Army Major General Kenneth L Privratsky, in the only full-length study of the logistics of the 1982 Falklands War, has described how five officers and 20 men arrived on the island during the first weekend of the conflict.2

I led the Royal Navy’s forward logistic unit. My first task was a survey of the island and its facilities. Ascension Island is well described in the official history: 38 square miles of the most hostile environment one can imagine.3 The nightmare landscape consists of volcanic ash and dust, clinker, broken rock, and lava flows. The island is geologically young, and the rock has had little time to weather, and I was struck by the sharpness of the rock apparently newly blasted from a quarry. Situated 8 degrees south and 14 degrees west in the trade winds, the island has a temperature of about 65 to 70 degrees Fahrenheit year-round, and a prevailing southeasterly breeze blows at about 18 knots on 364 days of the year. At sea level there is some six inches of annual rainfall. On my way there, I had had time to snatch a read of the Admiralty Sailing Directions, which told me that this rain falls as light showers or drizzle—but in early 1982, much of it fell in heavy tropical downpours that caused flash floods and large pools of water that quickly evaporated.

By contrast, Green Mountain, rising to nearly 3,000 feet at the island’s center, has some 20 inches of rain. Formerly, water was stored in catchments, but by 1982 these were disused. On the upper slopes of the mountain there was a derelict farm, an attempt by Cable & Wireless Ltd. to provide fresh meat and vegetables. The verdant appearance of Green Mountain contrasts starkly with the barrenness of the lower slopes. Some bays have beaches of soft white sand, but prohibitively steep-to and enclosed by sharp rocks. All around the island the unexpected swell, strong undertow, and offshore set, to say nothing of the voracious sea life (blackfish, moray eels, sharks), are a discouragement to swimming.

Ascension went unclaimed by any nation from its discovery in 1501 until 1815, when Royal Marines garrisoned the island to forestall any French rescue attempts of Napoleon in exile on Saint Helena 700 miles away. The island was one of the Admiralty’s “stone frigates,” HMS Ascension, until 1922, when control passed to the Eastern Telegraph Company.

During World War II, when the United States obtained a lease on parts of the island, the 38th Combat Engineer Battalion of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built an airstrip. On 15 June 1942, the first landing on Ascension by an aircraft was made by a Swordfish biplane on antisubmarine reconnaissance, flown from the escort carrier HMS Archer, one of the so-called Woolworth carriers.4

A Remote Rock’s Sparse Populace

By 1982, the temporary residents of Ascension were all employees or contractors of British companies and U.S. agencies working on the island, e.g., Government Communication Hedquarters (GCHQ), Cable & Wireless, BBC, Pan Am, South Africa Cable, NASA, the NSA, etc. In all, it was about 1,000 people, including 58 European families and 600 contract workers from Saint Helena, among whom there were some 200 schoolchildren, and about 200 unaccompanied American civilians. Unless employed by one of the companies or members of Her Majesty’s Forces on active service, no one else was allowed on the island.

The nature of the American base on Ascension was much misunderstood. The very words conjured up visions of acres of runway, several choices of clubs, a large PX, and unlimited resources. Little could be further from actuality. Part of the U.S. Eastern Test Range, “Wideawake” had a uniformed complement of one, the base commander, a lieutenant colonel. The U.S. mission was to track the many satellites that flew overhead; there was one 10,000-foot runway, and normal activity was two or three aircraft per fortnight. The island is sovereign British territory; the airfield and associated facilities were leased by the United States, which was obliged under treaty to provide logistical support to the British.

All services were run under contract by Pan Am, but there was certainly no base in any operational sense. In the words of Admiral Fieldhouse’s official despatch, Ascension was largely devoid of all resources and possessed “totally inadequate technical and domestic back-up.” As Royal Navy Rear Admiral John “Sandy” Woodward wrote, it would be a “tremendous piece of improvisation in very short order [as] Ascension was transformed from a U.S. communications and tracking station into a forward fleet and air base in a matter of days.”5

From Diverse Teams, a Big Buildup

The buildup of the forward operating base on Ascension from 25 officers and men during the first weekend to 800 personnel after three weeks, and then to a peak of 1,400 including transitees, happened in three overlapping phases. The initial phase was marked by crises that developed internally on Ascension, the second was a phase of intense operations, and the final phase was one of widening horizons before the organization was handed over in mid-July to the Royal Air Force (RAF) after victory in the Falklands.

The remarkable thing is that the organization developed and functioned without written orders for several weeks, yet succeeded so well in melding together diverse units, many of whose personnel had no experience of triservice operations. Though differences among the services in attitude and manning were revealed, force of personality, clear objectives, and daily and regular briefing united the teams.

Much, of course, depended on goodwill, of which there was an abundance among all, not least the Pan Am manager, Don Coffey, whose resource and ingenuity made him the key player on the U.S. side.6

An early discovery was that, although the reinforcement plan for Ascension Island had been recently revised in London, it had not been reviewed by the island authorities, and the contents were inaccurate and largely irrelevant. As I disembarked from my Hercules, a representative of GCHQ pressed a wadge of urgent signals into my hands. The organization that quickly developed was threefold: first, naval operations, including all rotary-wing aircraft; second, RAF operations, which in particular encompassed the tremendous achievements of RAF transport command; and third, logistics.

By noon on 6 April, when Captain Bob McQueen arrived as Commander, British Forces Support Unit, the base had been operating continuously for many hours. Three Lynx helicopters were flying, and two Wessex helicopters were preparing for ground running. In Clarence Bay, the fleet auxiliary Fort Austin was being loaded by lighter. Hercules transport aircraft were arriving regularly, about six or eight per day, but there was little control over the flow of men and cargo, and units and individuals brought with them whatever equipment they or their commanders deemed necessary. On 21 April, I noted that there were 300 helicopter movements involving 300 passengers and 400,000 pounds of freight.

After the Fort Austin sailed, it became an urgent necessity to reduce any risks on the airfield by creating a dedicated ammunition depot. An ideal site was found in a remote valley, but the only access was along a track liable to flash flooding. This led to an unusual demand for stores: I requested a pipe, 20 feet long and 4 feet in diameter and capable of withstanding a 10-ton axle weight, capable of being used as a conduit under a makeshift road. This arrived within two days of the demand, and ammunition was soon being trailered away from its unpleasant proximity to fuel, aircraft, and vehicles and into some temporary shade.7

A transport pool was formed by commandeering unit vehicles as they were unloaded from Hercules. In the early days, the officer commanding Royal Marines, 845 Naval Air Squadron, ran the pool, and the most conspicuous volunteer drivers were a group of young medical officers waiting to join ships. When the transport pool vehicles were depleted, night raiding parties removed the fuses from parked vehicles, thus forcing the would-be possessors to ask the transport officer for help, when he would promptly requisition the keys.

The Pan Am accommodation was capable of taking about 200 men. A campsite at English Bay, which had been used by RAF signalers after World War II and by West Indian contract labor later, provided a roof for some 50 men more. Units pooled tents and rations, and field kitchens were established. Fortunately, the Royal Navy regularly exercises setting up such kitchens as part of its emergency relief training. Eventually, three such field kitchens were set up, supervised by a Royal Navy catering officer, which fed more than 1,000 men a day. For a while, rations were one-man 24-hour type, donated by 42 Squadron RAF, requiring considerable wrist work to provide bulk meals. Very soon, however, the Royal Navy had moved in refrigerated containers and landed sufficient dry food to enable a varied and interesting diet.

However, I found a signal from the Ministry of Defence advising me to make maximum use of local purchase, i.e., to go shopping—this was somewhat irritating, and I must have been quite tired when told the MoD it was being unrealistic.

‘Busiest Airfield in the World’

At another stage, the senior RAF officer requested a halt to all helicopter movements for a window of an hour when large fixed-wing aircraft were due to arrive from the United Kingdom. There followed a quick conference between naval officers on the island when we agreed that Wideawake would be treated like an aircraft carrier, and the maximum window that could be allowed was a few minutes. It is claimed that the airfield at Wideawake became the busiest airfield in the world; this was confirmed by Don Coffey calling a chum at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. At least until early June, helicopter movements outnumbered fixed-wing movements by a ratio of more than 5 to 1.

The helicopters came from visiting warships, of course, and from the newly resident Wessex Vs of D Flight 845 Naval Air Squadron. Particular credit is due to the youthful naval pilots who flew more hours in the early days of April than they might have been expected to in a year of peacetime activity. There was no choice on Ascension but to run the single airstrip and limited hardstanding like an aircraft carrier, with rotary, and fixed-wing flying taking place simultaneously with the movement “on deck” of men, stores, and vehicles. The absence of ground and air safety incidents was attributable not to luck, but to the training and professionalism of all who participated.

Fuel, in particular aviation spirit, was a persistent problem. Fortunately, the island’s stocks for normal consumption were relatively large, but the frequent launch of large flights of aircraft necessary to support elderly, fuel-hungry Vulcan bombers and Victor tankers on operations over the South Atlantic soon depleted reserves. Fuel had to be pumped ashore from tankers anchored in Clarence Bay, but the fuel pumped from these ships required time to settle; a new tank farm of fabric pillows was established at Wideawake, and a fleet of bowsers increased reserves, but fuel always required careful management.

Perhaps the most important and war-winning supply that moved through the airhead at Wideawake were 100 Sidewinder 9L missiles on 15 May. The Sea Harrier/9L combo played the major part in the air victory over the Falklands, allowing low-level aircraft to turn away dozens of Argentine attack missions, significantly reducing the level of damage sustained by the amphibious force and its protective screen of warships. The early phases of this air war had been fought with a small stock of Sidewinder 9Ls, but in mid-May the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered the U.S. Air Force and Navy to rearm the British. I had only just returned from interrogating prisoners of war on board the fleet auxiliary Tidespring when these extra missiles arrived at 0200—and were quickly shipped south.8

The Devil in the (Expanding) Details

Much was a learning process, and practices had to be worked out from first principles. However, by mid-June the joint-logistics function had grown to cover supply, catering, medical, administration, transport, police, and accommodation, including re-equipping survivors and the repatriation of prisoners. The same principles and processes developed for evacuation of survivors (to arrive in time for the main UK news broadcasts) could be applied to repatriation of prisoners of war (who were flown at dead of night so that they could not observe operations at Wideawake). Admiral Fieldhouse’s order “to make things work” remained in the forefront of my mind as I set up contracts to draw stores from the BBC and Cable & Wireless workshops, and while I commandeered in-flight rations from the RAF to feed to island’s burgeoning population.

It was pleasing that many flattering words have written about the “logistics miracle” that was wrought on Ascension Island in 1982. The commander-in-chief wrote that Captain Bob McQueen “had a difficult task to perform, requiring great tact and working under enormous pressure. That he succeeded was crucial to the success of the operation,” and Commodore Mike Clapp, Commander of the Amphibious Task Group, thought that “without Ascension Island, there would have been no Operation Corporate.”9

But perhaps the best words were about the “indomitable supply officer whose influence on the smooth flow of the operation was unruffled and benign.”10

1. Oliver Franks, The Franks Report: Falkland Islands Review (London: Pimlico, 1992), 73–74.

2. Kenneth L Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War: A Case Study in Expeditionary Warfare (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword, 2014), 63.

3. Peter Hore, “Logistics Operations on Ascension Island 1982,” The Naval Review, 80 (1992): 343–44; Lawrence Freedman, The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 2, War and Diplomacy (London: Routledge, 2005) 62; and David H. Brown, The Royal Navy and The Falklands War (London: Leo Cooper, 1988), 69–70.

4. “Ascension Island: World War II.”

5. Sandy Woodward and Patrick Robinson, One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander (London: HarperCollins, 1992), 86.

6. Julian Thompson, 3 Commando Brigade in the South Atlantic (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword, 1992), 23.

7. Robert McQueen, ed., Island Base: Ascension Island in the Falklands War (Caithness, UK: Whittles Publishing, 2008), 78–79.

9. London Gazette, Despatch by Commander in Chief of the Task Force Operations in The South Atlantic: April to June 1982 (London: HMSO, 1982), 16111; M. C. Clapp and Ewen Southby-Tailyour, Amphibious Assault Falklands: The Battle of San Carlos Water (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword, 1994).

10. McQueen, Island Base, 32.