Rarely in the annals of military history has the loss of one ship, especially a merchant vessel, had such an impact on the course of battle as did the sinking of the SS Atlantic Conveyor during the Falkland Islands War. In April 1982, Argentina invaded the Falklands, which had been a British colony for nearly 150 years. After decades of positioning itself to fight a war in Europe alongside its Western allies, Britain was ill-prepared to go it alone 8,000 miles from its shores.

Loading a Container Ship for War

The Royal Navy had been stripped of significant carrier-based aircraft and airborne early warning (AEW) components during the 1960s and 1970s.1 Indeed, of the service’s two aircraft carriers, one (HMS Invincible) had already been sold to Australia though not yet transferred and the other (HMS Hermes) was slated to be scrapped.2 Cargo capacity also was limited, and several dozen merchant ships were drawn into service to join the fleet sent to retake the Falklands. One of them, the Atlantic Conveyor, a 12-year-old, 15,000-ton civilian container ship, was to play an important role in the effort. The Board of Inquiry into her loss would shed light on hard lessons that are still significant for present-day naval forces.

After war broke out, the Atlantic Conveyor initially was retrofitted to function as an additional flight deck for helicopters and Harrier vertical take-off and landing jets. However, it soon was determined that her holds would be needed for the massive logistical supply operation required to fight a war in the South Atlantic. In the end, she was loaded with 14 Harriers (8 Fleet Air Arm Sea Harriers and 6 Royal Air Force Harrier GR.3s), 5 Chinook HC.1 heavy-lift helicopters, 6 Wessex HU.5 helicopters, several hundred aircraft cluster bombs, and 80 tons of kerosene. Also packed on board were tents for several thousand troops along with their associated kitchens and sanitary facilities, desalination supplies, portable fuel bladders, small boats, matériel-handling equipment, generators, metal matting for the creation of a land base for the Harriers, missiles, ammunition, and numerous other vital supplies.3

The two Royal Navy aircraft carriers together embarked only 20 Harriers; the additional 14 transported in the Atlantic Conveyor increased their numbers by 70 percent. These were the only British fixed-wing aircraft available for carrier operations during the war. It could be argued that the transport was one of the most important ships in the fleet when it came to providing fighting capacity; however, she was not fitted with any self-defense capabilities. This would have fatal repercussions that reverberated throughout the upcoming land campaign.

The Exocet’s Deadly Role

Nearing the end of May 1982, British and Argentine forces had been engaged in combat operations for nearly a month. Two Royal Navy Type 21 frigates, HMS Ardent and Antelope, had been sunk along with the guided-missile destroyer HMS Sheffield. The Argentine cruiser General Belgrano also had been sunk, and nearly two dozen Argentine aircraft had been shot down. The loss of the Sheffield was particularly concerning because she had been hit by an Exocet missile, against which the Royal Navy had limited defensive capability, and Argentina was believed to have five of the weapons. That version of the French-built AM39 Exocet traveled at nearly the speed of sound at sea-skimming height, weighed nearly 1,500 pounds, and carried a 364-pound warhead.

Only two British warships in the battle group carried the Sea Wolf missile system, which had been designed to shoot down low-flying high-speed targets. Ironically, it was credited with downing only five of the 117 Argentine aircraft lost during the war, whereas naval cannon and small-arms fire accounted for seven shoot-downs.4 Throughout the fleet, visually aimed, manually operated machine guns were lashed to ship railings as a last-ditch point-defense against the missile and aircraft threats.

The British military expected an especially intensive effort by the enemy on 25 May, a patriotic holiday in Argentina. By early afternoon the guided-missile destroyer HMS Coventry had been sunk after being hit by multiple unguided aerial bombs. Later in the day, Agave radar emissions from French-built Super Étendard strike fighters—the only known Argentine aircraft capable of carrying the Exocet missile—were detected. Ships fired decoy chaff rockets and guns while taking evasive maneuvers. Two missiles passed through or under the chaff cloud launched by the Type 21 frigate HMS Ambuscade. The missiles then locked onto the next target in their path—the Atlantic Conveyor—and slammed into her.

Approximately three minutes had passed between radar detection and impact. Though the transport stayed afloat for three days, the fire inside her was uncontrollable, and the detonation of explosive materials belowdecks eventually blew off her bow. Twelve lives were lost, and the ship sank with three Chinook and six Wessex helicopters, along with her critical stores, still on board. Fortuitously, the 14 Harrier jets had been flown over to the aircraft carriers a few days before. The Ambuscade valiantly had done what she could to defeat the incoming Exocets, but the frigate carried the Seacat surface-to-air missile system, not the Sea Wolf system. The former had been developed in the 1950s, and its missiles weighed 138 pounds and had a range of only approximately three miles.5

Rear Admiral John Forster “Sandy” Woodward, the carrier/battle group task force commander, would later state that a special debt is owed to the Atlantic Conveyor because behind her the next ship in the path of the missiles was the carrier Hermes.6 Damage to or loss of one of the two aircraft carriers potentially would have altered the course of the war.

The threat posed by the Exocets was a constant concern. When it was learned in late May that France was in the process of selling a shipment of them to Peru, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher implored French President François Mitterrand to halt the sale because it was believed Peru would relay the missiles to Argentina.7 France would resume arm sales to Argentina only a couple of months after the war and go on to provide dozens of Exocets and Super Étendards over ensuing years.8

Inquiries into the Loss

The official Board of Inquiry report into the loss of the Atlantic Conveyor would be released to the public, and some of the findings caused a furor. In the initial planning stages of Britain’s response to the Falklands invasion, it was noted that the transport would be in the combat zone, but this did not lead the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to provide her with any self-defense capabilities, such as chaff rockets or guns. Though this was chalked up as an oversight due to limited time and the need for expediency, there was also controversy within the ministry as to whether or not it was legal to do so.

Another declassified report by the MoD to the Prime Minister noted that the ship lacked self-defensive capabilities and it was nearly impossible to intercept an Exocet except straight down the targeted vessel’s line of sight.9 In addition, once the Harrier jets had been disembarked, the Atlantic Conveyor apparently was not deemed a high-value asset, although she still carried an enormous amount of supplies, helicopters, fuel, munitions, and equipment.10 Further vagaries with regard to how military explosives and combustibles were stored on board and the civilian crew’s lack of knowledge and/or training about their characteristics were also noted in the Board of Inquiry report.

Repercussions of the Sinking

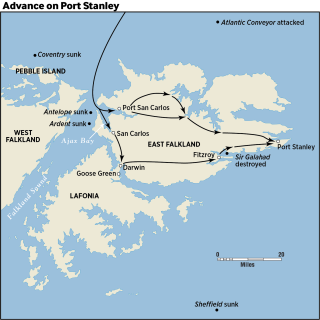

During the weeks after the Atlantic Conveyor was sunk, British ground forces acutely felt the loss of the ship. Movement of troops across 50-mile-wide East Falkland Island to the capital of Port Stanley was intended to be done using the transport’s helicopters, especially the heavy-lift Chinooks.11 Without most of them, paratroopers and Royal Marines found themselves having to execute what became known as “the Great Yomp” (yomp is slang for a long march with full kit), which likely extended the war.

The limited supply of helicopters meant there was a constant tug-of-war between the need to move troops versus supplies and ammunition. As a logistical example, it was calculated that using lesser-capacity Sea King helicopters would require 85 individual sorties just to move one six-gun 105-mm artillery battery with 500 rounds of ammunition per gun.12 Third Commando Brigade’s commander noted that at times his artillery guns were able to fire only 16 rounds each per day because of limited resupply.13

The weather in the Falklands is notoriously poor, and being in the southern hemisphere, the islands were entering fall/winter when combat started. Daily temperatures in June range between 40 degrees Fahrenheit during the day and near freezing at night, with winds averaging around 19 mph.14 Major roads generally were not paved, the terrain is rocky, and the ground rarely is completely dry at that time of the year. Needless to say, conditions were brutal, and many troops sustained cold-weather injuries that were still notable months after the war.15 It was nearly impossible to keep dry, with wet feet especially being a problem, which led to misery during the long march across the island.16

The loss of tenting and associated equipment on board the Atlantic Conveyor added to the austere circumstances for British troops and, later, Argentine prisoners of war. Overall, the loss of the helicopters on board the ship greatly impaired mobility for the ground forces. This ultimately would lead to the decision to move some troops by sea to the east side of East Falkland Island. In Bluff Cove, Argentine air attacks on the landing ships while unloading the soldiers led to the deaths of 51 servicemen, the wounding of several dozen, the loss of one vessel (RFA Sir Galahad), and damage to others.17 The Bluff Cove air attacks accounted for the largest loss of British lives during the entire war.

The task of recapturing the Falkland Islands required the Royal Navy to fight a war with major deficits in military intelligence, airborne early warning (AEW), and ship design/technology—all of which played a role in the sinking of the Atlantic Conveyor. Admiral Woodward and other officers later would comment that much of their initial intelligence about enemy capabilities came from commercially available reference books and libraries.18 There also was considerable confusion about the best way to evade the Exocet, and the information provided to the Royal Navy was deemed contradictory by some officers.19 For many years, the British MoD had talked itself into believing that any future war would be against the Soviet Union while apparently turning a blind eye to many decades of Argentine–British posturing and saber-rattling.

An Unheeded Warning

In 1979, First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff Admiral Terence Lewin had given a lecture in which he pointed out that airborne early warning aircraft would be vital in any future war. However, this was with the expectation these would be land-based aircraft, because the only Royal Navy ship capable of carrying AEW aircraft (HMS Ark Royal) had already been decommissioned.20 He went on to state that Sea Harriers would be supplemental to land-based fighter aircraft and that the Sea Wolf missile system would need to intercept incoming enemy missiles.21

Three years later, the Royal Navy was sent to war without any AEW aircraft or enough Sea Wolfs. The lack of AEW allowed Argentine pilots to launch their Exocet missiles at a range of only 20 miles during their attack on HMS Sheffield and 22 miles against the Atlantic Conveyor—extremely short distances in modern warfare.22 As was noted in an air defense report, a Type 21 frigate such as HMS Ambuscade was expected to defeat modern high-speed jet aircraft with only the Seacat missile system and two manual single-barrel 20-mm guns, whereas a World War II vessel of the same size was armed with two dozen or more guns to take down propeller-driven aircraft.23 The effectiveness of missiles against a swarming low-flying enemy was limited. Estimates are that the Seacat system had a success rate of only 10 percent.24 Adding to this was a tendency by the MoD, along with Her Majesty’s Treasury, to design and build ships with an eye on cost and exportability.25 This limited potential armament and radar upgrades, especially in the frigate class that included the Ambuscade, Ardent, and Antelope.26

Britain had presumed a future war would be against Soviet forces and equipment close to her shores. It expected that the Royal Navy would fight alongside the ships and aircraft of her allies. In the spring of 1982, the speed and efficiency with which civilian vessels were brought into military service was admirable, but not providing them with their own self-defense capability was costly in lives and matériel. The Atlantic Conveyor was a vital part of the war effort, but she succumbed to a lack of foresight. The total lack of AEW aircraft within the fleet meant that picket ships were needed to provide notice of an air attack, leaving them in exposed positions. Lastly, placing so much important equipment and 70 percent of available fixed-wing carrier aircraft on board one vessel that was also packed with hundreds of tons of explosives and fuel was highly questionable.

1. Keith Speed, Sea Change (Bath, UK: Ashgrove Press, 1982), 22.

2. Max Hastings and Simon Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1983), 11.

3. British Royal Navy, Board of Inquiry Report: Loss of SS Atlantic Conveyor (21 July 1982); David Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987), 230.

4. Ministry of Defence white paper, “The Falklands Campaign: The Lessons,” 12 December 1982, 45.

5. Norman Friedman, The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapons Systems (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1989).

6. John Woodward and Patrick Robinson, One Hundred Days (London, UK: Fontana Press, 1992), 298.

7. Margaret Thatcher, declassified communiqué, Telegram #311 (30 May 1982) to French President François Mitterrand, Margaret Thatcher Foundation, margaretthatcher.org.

8. “Paris, Breaking Ranks, Ends Argentina Arms Ban,” The New York Times, 11 August 1982; SIPRI Arms Transfers Database (data report generated for 1982 to 1992), sipri.org.

9. British Ministry of Defence, “Exocet Attack, 25th May,” to the British Prime Minister, 2 June 1982, the Margaret Thatcher Foundation, margaretthatcher.org.

10. British Royal Navy, Board of Inquiry Report: Loss of SS Atlantic Conveyor.

11. Kenneth Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books Limited, 2014), 126.

12. Privratsky, Logistics in the Falklands War, 128.

13. Ian Speller, “Limited War and Crisis Management: Naval Aviation in Action from the Korean War to the Falklands Conflict,” Tim Benbow, ed., British Naval Aviation: The First 100 Years (Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2011), 171.

14. Climate and Average Weather Year Round in Falkland Islands, weatherspark.com.

15. Francis Golden, Thomas Francis, Deborah Gallimore, and Roger Pethybridge, “Lessons from History: Morbidity of Cold Injury in the Royal Marines during the Falklands Conflict of 1982,” Journal of Extreme Physiology and Medicine 2, no. 1 (December 2013): 23.

16. Nick Vaux, March to the South Atlantic (Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword Books, 2007), 130–31.

17. Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 302.

18. Woodward and Robinson, One Hundred Days, 78; Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 90.

19. Hastings and Jenkins, The Battle for the Falklands, 132.

20. Speed, Sea Change, 22.

21. Terence Lewin, “The Royal Navy: Present Position and Future Course,” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 127, no. 5277 (August 1979): 561–75.

22. Brown, The Royal Navy and the Falklands War, 141, 228.

23. LCDR James Haggart, USN, “The Falkland Islands Conflict, 1982: Air Defense of the Fleet,” paper presented to the Marine Corps Command and Staff College, 2 April 1984 (Alexandria, VA: Defense Technical Information Center, 1984).

24. Alastair Finlan, “War Culture: The Royal Navy and the Falklands Conflict,” Stephen Badsey, Mark Grove, and Robert Havers, eds., The Falklands Conflict Twenty Years On: Lessons for the Future (New York: Taylor & Francis, 2005).

25. Speed, Sea Change, 19–20; Robert Gardiner, ed., Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1947–1982: The Western Powers (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1983), 166.

26. Gardiner, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1947–1982: The Western Powers, 166.