Just because a plan does not work as intended does not mean it was unsuccessful. The Union blockade of the Confederacy during the Civil War certainly counts as an example. By one estimate, Confederate steamers successfully penetrated the Union blockade into North and South Carolina ports over 90 percent of the time, a rate that raises serious doubts about the blockade’s effectiveness. Yet despite the seeming porousness of the Union Navy’s efforts, the effects of the blockade were still devastating to the Southern economy. The relevant question, then, is “Why?”

The root challenge is that blockades are really economics problems nested within a warfare problem. For planners, the issue starts with getting the economics right, and then applying military pressure in a way that achieves the desired outcome. This begins by acknowledging that not every economy is even susceptible to blockade. For a blockade to work, the target economy must depend on imports or exports, the blockading power must have the means to effect the blockade, and neutral/nonaligned powers must lack the desire or ability to bypass the blockade.

The Confederate Economy’s Susceptibility

Conceptually, the prewar Southern economy met the basic requirements for a successful blockade. Part of a larger globalized supply chain, the keystone of the economy was cotton, typically produced on large slave-holding plantations of the Deep South—North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana, basically the states which seceded prior to Fort Sumter. Highly profitable and generating relatively greater wealth than other regions of the United States, the economy of the region was built on exporting cotton internationally to the United Kingdom and intra-nationally to the Northeastern states. The export proceeds from cotton then were used to purchase manufactured goods from other regions of the United States as well as from abroad, while foodstuffs (beef, hogs, corn, rice, etc.) typically were obtained either from the outlying Southern states of Texas and Arkansas or the Midwestern states of Ohio and Illinois. Put more simply, within the Confederate economy, states east of the Mississippi produced money while states west of the Mississippi produced food. Economically, that distinction matters.

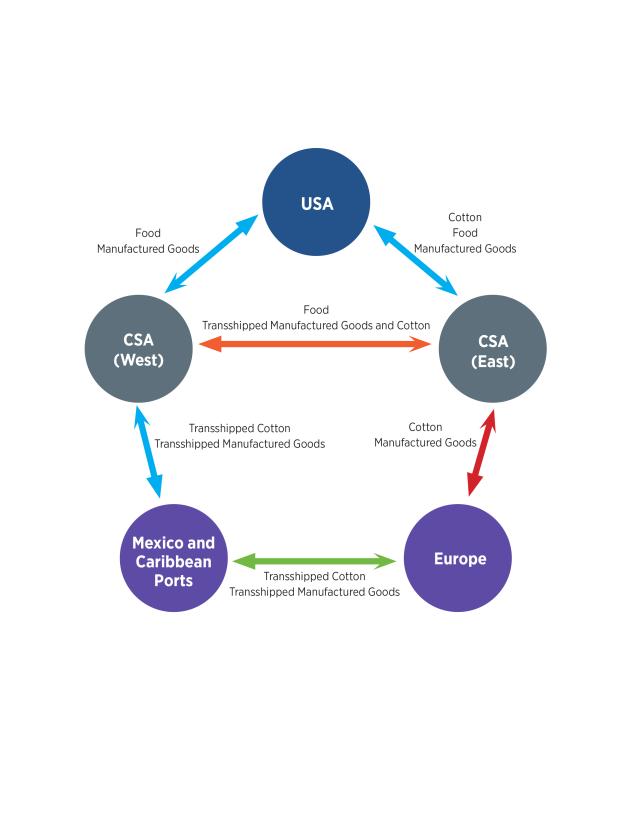

The reliance on cotton exports coupled with the geographic division of food production also meant the prewar Southern economy was highly dependent on maritime trade and therefore vulnerable to a blockade. Conceptually, this can be seen using a “linkages” Input/Output framework as developed by Wassily Leontief to identify targets during World War II. The Confederate economy can be thought of as two nodes: the cotton-producing “CSA East” and the food-producing “CSA West,” which then were linked to the Northern states as well as to European and neutral economies through a series of bilateral trade relationships. A simple graphical representation describing these nodes as well as their primary trade linkages is depicted in Figure 1:

Understanding this economy’s vulnerability is fairly easy: conflict with the North would sever the linkages between the CSA and the USA, while blocking the connections with Europe (whether directly or through neutral ports) would starve the Confederate economy of both the matériel and money necessary to wage the war. This then gave the Union blockade its fundamental objective: to physically cut off the Confederacy from Europe (represented by the red two-way arrow).

Whether or not that happened is debatable. In practice, what occurred was both more nuanced and more devastating. For while the direct international trade in cotton attracted the most money and the most attention, it was the unglamorous interstate trade in food (the orange two-way arrow) that proved the most critical to the Confederate war effort. Essentially—and not altogether intentionally—the Union blockade balkanized the Confederate economy into two different non-supporting spheres, physically separating the Southern food supply west of the Mississippi from the financial resources east of the Mississippi. This schism then overstressed the Confederate surface transportation system, forced capital expenditures on resources to break the blockade, and triggered ruinous inflation that seized-up the entire Confederate economy.

What neither side fully appreciated at the start of the conflict was just how sophisticated (and, quite frankly, more modern) the Confederate economy was. Economies are, above all, dynamic social systems. Under stress, they will attempt to evolve away from damage. The model previously described assumes trade along very specific bilateral lines. Disruptions in any of these lines can trigger a systemic failure. However, these disruptions will also create incentives and opportunities for substitution in supply chains or innovation in production processes to mitigate these effects. The economy will continue to substitute and to innovate until either the stress is dissipated, or until all opportunities for substitution and innovation have been exhausted and the economy fails.

That is what the Southern economy did. The blockade initially targeted European cotton exports because that was the prewar Southern economy. However, the blockade also triggered a series of changes within the Southern economy that the Confederacy ultimately could not sustain. Essentially, the blockade succeeded not because it achieved its initial objectives, but rather because it forced the Confederate economy to adapt more than it could react. It is that forced inability to react that is relevant to modern-day planners contemplating economic warfare.

How It Worked, What It Did

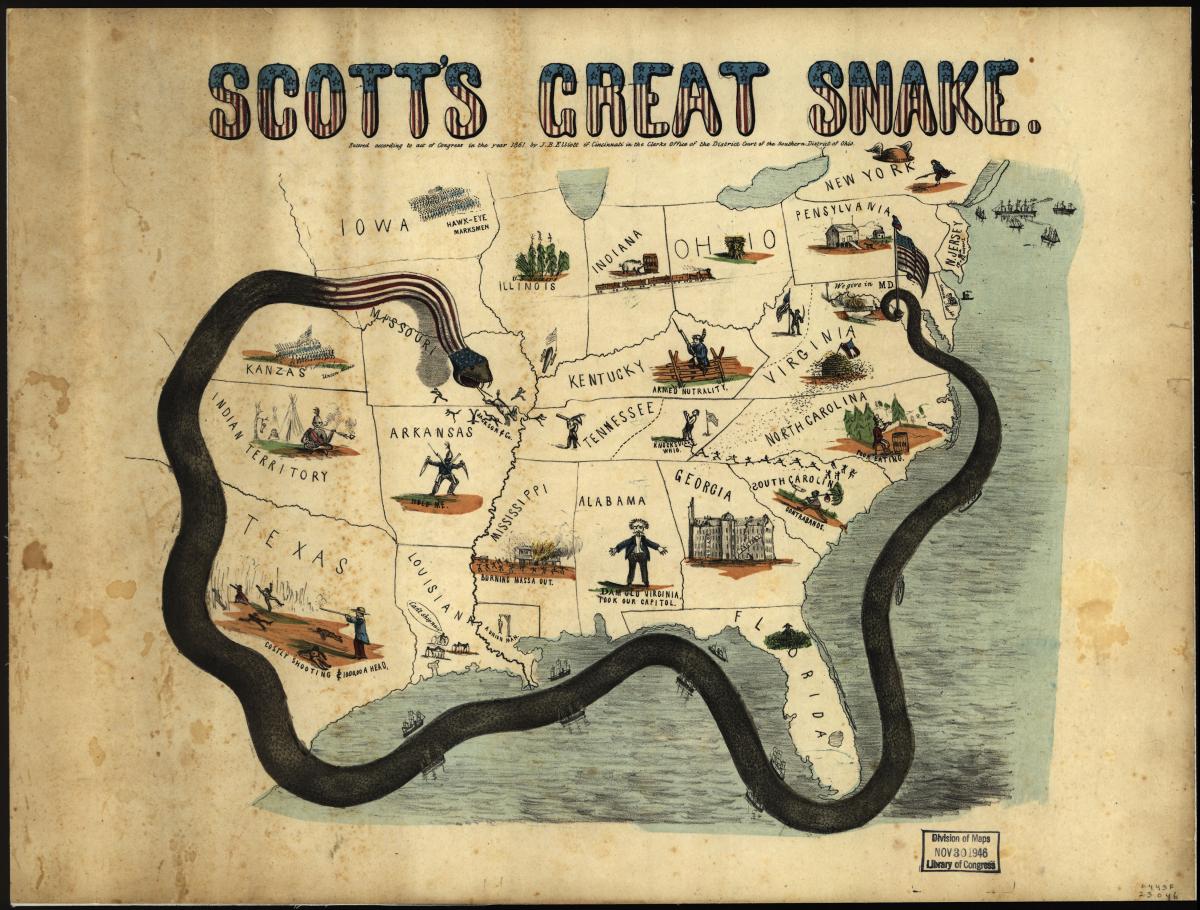

Following the declaration of the blockade by President Abraham Lincoln, U.S. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles quickly established two blockade zones. The first basically extended from Virginia to the Florida Atlantic Coast, while the second covered the Gulf Coast of Florida to Texas. Overly large and involving significant transit times for the relatively small number of ships (fewer than 100) initially available to the blockading fleet, it was clear early on that the Navy needed to establish a more deliberate strategy for the blockade. At the direction of Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox, the Navy created a Blockade Board under Flag Officer Samuel Du Pont in the summer of 1861 to formulate a more coherent and effective blockade policy.

From this came the Navy’s basic maritime strategy. Relying on a blockade in depth, the blockade employed armed pickets close to shore (more often than not, lightly armed former merchant vessels), faster and more heavily armed steam frigates patrolling offshore in support, and globally roving cruisers to interdict Confederate blockade runners on the high seas or to intercept Confederate commerce raiders. To landward, the Navy cooperated with the Army in amphibious and coastal/riverine operations to gain control of riverways and ports. The blockade is then best seen as part of a larger combined-arms strategy aimed at splitting the Confederate economy.

The operational effectiveness of this approach is an open question among economists and historians. Some analysis suggests that while highly profitable, blockade running was sufficiently risky that fewer than 10 percent of blockade runners challenged the blockade more than once. However, effective operational security measures (renaming ships, shifting ports of entry, changing ships’ registries, etc.) may bias that number downward. Additionally, it appears that, at least for the Carolina ports, blockade runners successfully penetrated the Union cordon in 90 percent or more of attempts. Consequently, the entire Northern blockade effort has been described as a “sieve.”

Ironically, the permeability of the blockade may not have mattered, and here is where the lessons lie for contemporary planners. The ultimate measure of the blockade’s effectiveness was how it affected Confederate combat power. The original objective of the blockade was to cut off the physical inflow and outflow of resources into the Confederacy, particularly in the east. It may not have achieved that. What it did accomplish, however, was to fracture Confederate distribution and sustainment. Seizure of Southern ports not only provided coaling and sustainment facilities that improved station-keeping time for the blockaders; it also simultaneously channelized Confederate blockade running into fewer and fewer ports. This, in turn, created the principal effect of the blockade. Largely due to the seizure of ports and the deterrent effects of near-shore patrols, Confederate supply lines shifted away from coastal shipping and onto an inadequate and overstressed Southern railway network. Consequently, while significant volumes of matériel entered Confederate ports, they could not leave; the “orange arrow” failed.

Seizure of the Mississippi compounded the Confederates’ logistics problem. Split in two and unable to access cattle in Texas, rice in Arkansas, or salt in Louisiana, the Confederate operating forces in the East began cutting rations following the fall of Vicksburg, and food became incredibly scarce across the Confederacy. Supply chains faltered not for a lack of abundance, but for a lack of transportation. Operationally, the blockade achieved the most effective end state: The Confederacy could not sustain its forces in the field. Returning to the model described in Figure 1, the U.S. Navy sought to break the “red arrow,” but instead broke the “orange arrow”—which still achieved the desired results.

Lessons for Contemporary Planners

Economically, the key point is that while the blockade targeted physical inputs/outputs, it was the destruction of two interrelated capabilities (distribution and sustainment) that proved decisive. In hindsight, it becomes apparent that the Confederate transportation sector could not adapt to the stresses of the blockade. The South needed to find a substitute for coastal shipping but lacked the railroad capacity to absorb the increase in demand on surface transportation caused by the blockade. More critically, the South also lacked the internal capability to expand railroad capacity. The blockade exerted pressure on transportation, the least flexible and least adaptable sector of the Confederate economy; the inability to move goods then manifested itself in shortages of the least substitutable commodity, food.

The Confederacy attempted to innovate around this problem. Purpose-built blockade runners replaced conventional merchant vessels. New weapons technologies—ironclad warships, mines, submarines, etc.—were developed in efforts to break the Union blockade and regain access to maritime trade. Essentially, the CSA sought to defend the “red arrow.” However, not only did these innovations ultimately fail, in several regards they compounded the Confederacy’s economic problems. By increasing demand for imported iron, steel, and engines, attempts to innovate around the Union blockade accelerated the decline of the already frail Confederate transportation system.

There’s more. Every physical trade linkage carries with it a corresponding financial connection; Money must move just as easily as goods for the economy to function. When goods and services ceased to flow through the rebel states, the Confederacy’s monetary system also failed. Hoarding and shortages in population centers drove up prices in ruinous inflation that crippled the remaining physical linkages within the economy.

Inadvertently, the Union Navy discovered two truisms of economic warfare. The first is that supply chain disruption is most damaging when an economy loses its ability to substitute for a commodity, or a capability hits its limits for substitution. For contemporary planners, the lesson is that the physical effects of a blockade, measured through changes in imports and exports, may be significantly less important than how the blockade affects the ability to distribute matériel. The critical effect is the stress on the economy as a system and breaking its ability to adapt.

The second is that monetary impacts can be just as damaging as physical impacts. Losing the capacity to buy materiel leads to the exact same outcome as losing the materiel itself: empty supply chains. As a result, when executing economic warfare, the effects of a blockade on a target nation’s monetary system must be evaluated in the same manner as the physical effects of the blockade. Simply put, money is also a target.

Not as Briefed, but Not Unsuccessful

When evaluating the effectiveness of economic warfare, examining the economy as a whole system is crucial. The existence of multiple and simultaneous linkages within and across economies means that economies can and will substitute around stresses until either the stress dissipates, or the economy runs out of options and breaks. Close examination of the U.S. Navy’s blockade of the Confederate economy shows just that outcome. The Navy targeted cotton—but broke the South’s transportation network, food supply, and monetary system instead. And any blockade that breaks an opponent’s economy is an effective blockade, regardless of how it is accomplished.

1. Bern Anderson, By Sea and by River: The Naval History of the Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962).

2. Lance E. Davis and Stanley L. Engerman, Naval Blockades in Peace and War: An Economic History since 1750 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

3. Robert William Fogel and Stanley L. Engerman, Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Slavery (Boston: Little, Brown, 1974).

4. Mark Guglielmo, “The Contribution of Economists to Military Intelligence During World War II,” The Journal of Economic History 68, no. 1 (March 2008): 109–150.

5. Bruce W. Hetherington and Peter J. Kower, “Technological Diffusion and the Union Blockade,” Explorations in Economic History 48, no. 2 (2011) 310–24.

6. Bruce W. Hetherington and Peter J. Kower, “A Reexamination of Lebergott’s Paradox About Blockade Running During the American Civil War,” The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 2 (June 2009): 528–532.

7. R. Douglas Hurt, American Agriculture: A Brief History, rev. ed. (West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2002).

8. Stanley Lebergott, “Through the Blockade: The Profitability and Extent of Cotton Smuggling, 1861–1865,” The Journal of Economic History 41, no. 4 (December 1981): 867–888.

9. James M. McPherson, War on the Waters: the Union and Confederate Navies, 1861–1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012).

10. W. N. Medlicott, The Economic Blockade, vol. 1 (London: His Majesty's Stationary Office, 1952).

11. Mancur Olson, “The Economics of Target Selection for the Combined Bomber Offensive,” Royal United Services Institution Journal 107, no. 628 (1962): 308–14.

12. Andrew F. Smith, Starving the South: How the North Won the Civil War (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2011).

13. William N. Still Jr., “A Naval Sieve: The Union Blockade in the Civil War,” Naval War College Review 36, no. 3 (May–June 1983) 38–45.

14. David G. Surdam, Northern Naval Superiority and the Economics of the American Civil War (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2001).

15. Craig L. Symonds, The Civil War at Sea (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2009).

16. Mark Thornton and Robert B. Ekelund Jr., Tariffs, Blockades, and Inflation: The Economics of the Civil War (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 2004).

17. Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running during the Civil War (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1988).