In years before World War I (1914–18) and in the decade following, there were numerous air races in the United States and Europe. The most famous of these aerial speed contests was the international competition known as the Schneider Cup Races. Jacques Schneider, a wealthy French aero-enthusiast, originated the races as a stimulus for seaplane design and the development of overwater flying. The competitions were administered by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale and offered a trophy valued at some $5,000.1

The races were for seaplanes and had to be flown entirely over water for a minimum distance of 150 nautical miles. Competitors raced against the clock, not each other, with the fastest average time winning. And the races had to be international in character. The first Schneider race was held in 1913, with the United States represented by a privately sponsored entry. The races were suspended during World War I, then resumed in 1919.

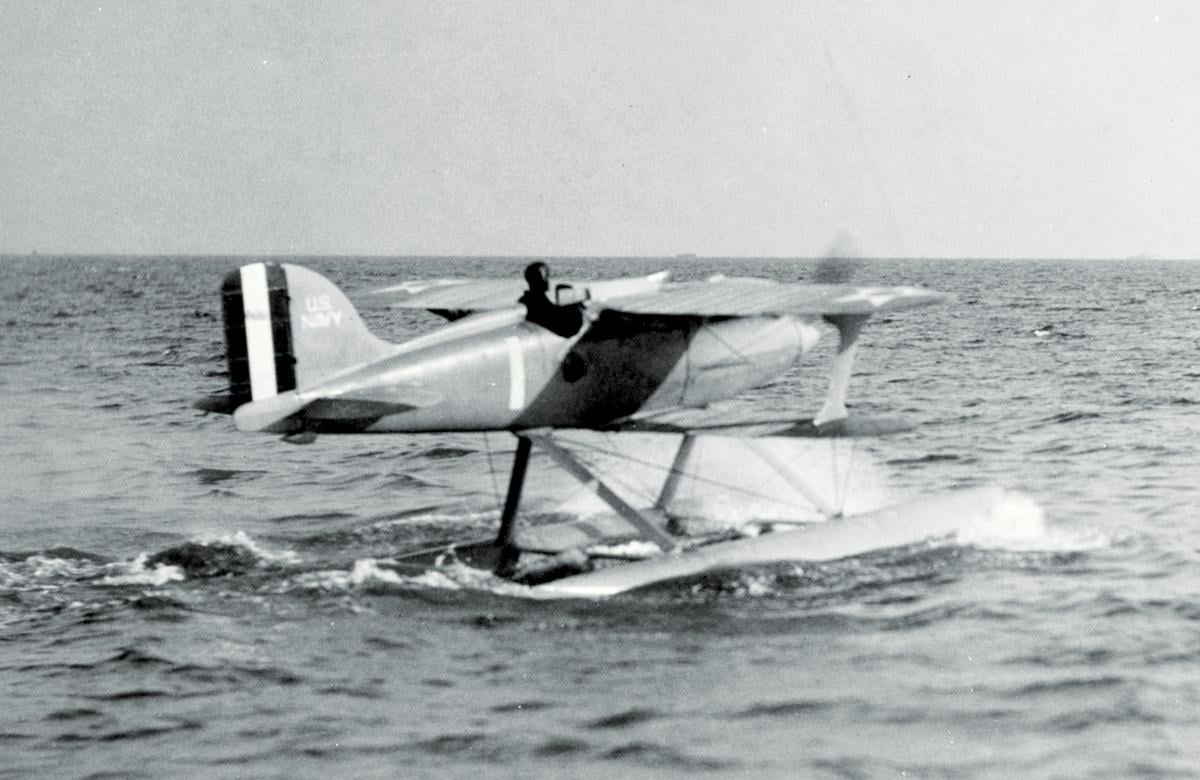

Subsequently, the U.S. military entered the Schneider races three times. The U.S. Navy–Curtiss racers twice won first and second places.

In 1921, the Navy decided to compete in the Pulitzer Trophy Race, which the Army had won the previous year. Curtiss was the only major U.S. aircraft firm with prior experience in racer design, and on 16 June 1921, the Navy awarded the firm a contract for two aircraft. The Navy had no effective designation scheme, so the aircraft were designated Curtiss Racer (CR) No. 1 and CR No. 2 (which was retained in naval service).2

Designed by Mike Thurston and Henry Routh and built at Garden City, Long Island (New York), these were streamlined biplanes with a single, open cockpit. Their original 425-horsepower engines operated on a mixture of 50 percent Benzol and 50 percent gasoline. A variety of drag-reducing features were incorporated. Both CRs had wheeled undercarriages, but there were slight differences in the two aircraft.

The first CR was test flown on 1 August 1921. That same year the CR-2 was “borrowed” from the Navy by Curtiss, and its test pilot easily captured first place in the Pulitzer race with a speed of 176.7 mph. The aircraft later attained 197.8 mph. The CR-2 was modified for the 1922 Pulitzer races. Flown by a Navy pilot, it came in third place behind two Curtiss R-6s. The Navy plane flew at 193.2 mph.

Both the CR-1 and CR-2 were reconfigured as seaplanes with twin floats for the 1923 Schneider Trophy Race to be held in England. Redesignated CR-3s, they were further modified, fitted with 475-horsepower engines, and had their wood propellers replaced with ones of forged aluminum.

The Navy won first and second place in the 1923 Schneider race; the CR-2/CR-3 won at 177.4 mph and the CR-1/CR-3 finished at 173.5 mph. The former aircraft subsequently set a world closed-course seaplane record of 188.07 mph. (All European entries withdrew from the 1924 Schneider race, to be held in the United States; rather than win by default, the United States canceled the meet.)

The Army won the 1922 Pulitzer race with the new Curtiss R-6 racer, which led the Navy to order two similar aircraft in 1923. Designated R2C-1, these “logical” developments of the CRs and R-6s included improved engines that were boosted to 507 horsepower. On 6 October that year, Navy pilots captured first and second place in the Pulitzer race with speeds of 243.68 mph and 241.77 mph, respectively. Both speeds were later exceeded by those aircraft. In 1923, after the race, one of the R2C-1s was “sold” to the Army for $1 (becoming the Army’s R-8).

The surviving R2C-1 was converted from wheels to floats for the (canceled) 1924 Schneider race.

For the 1925 race season, the Army and Navy teamed up to procure three improved aircraft from Curtiss, all designated R3C-1. These were land planes, similar to the R2C-1 except for the larger, 565-horsepower engine. Two of the aircraft raced in the Pulitzer that year, with an Army pilot gaining first place with 248.99 mph and second place going to a Navy flier attaining 241.7 mph. Those speeds were disappointing.

J. M. Caiella

After the Pulitzer race, all three aircraft were fitted with twin floats for the 1925 Schneider race. In the seaplane configuration they were designated R3C-2. The Army’s R3C-2—piloted by First Lieutenant James (Jimmy) Doolittle—finished first at 232.17 mph. The next day, over a straight course, he set a world speed record of 245.7 mph. The Navy had entered two R3C-2s in the race that did not finish. (The next year Doolittle received the Mackay Trophy for his feat.)

For the 1926 Schneider race the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia reworked an R3C-2, fitting it with a 700-horsepower Packard engine. That aircraft, now an R3C-3, reached a speed of 255 mph but crashed in a test flight. In the 1926 Schneider race, a Marine pilot came in second place at 231.36 mph. He flew the same R3C-2 aircraft that Doolittle had piloted the previous year.3

Another 1926 entry was a Navy–Curtiss F6C-1 Hawk, a standard Navy fighter. It achieved fourth place with a speed of 136.95 mph.

One R3C-2 was returned to Curtiss for further modifications for the 1926 race and was fitted with new floats and a new engine. As the R3C-4, this aircraft was in second place in the 1926 race when it was forced out on the last lap, averaging 242.16 mph.

According to Marine Lieutenant Colonel Robert Rankin:

Although this country participated officially in the Schneider event for only three years . . . it did gain considerable technical data from the contests. In addition to the goodwill engendered by the Navy pilots, the races were of positive value in drawing the attention of the general public to our naval air program in that period following World War I when it was all too fashionable to criticize the services. More important, of course, were the research aspects of the contests, the results of which led to many important aircraft improvements and developments.4

1. Introduction derived from LCOL Robert H. Rankin, USMC, “The Navy’s Schneider Cup Racers,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 81, no. 7 (July 1955): 802–7. The Schneider Trophy is now held at the Science Museum, South Kensington, London.

2. Aircraft descriptions are based on Peter M. Bowers, Curtiss Aircraft 1907–1947 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1979), 228–38. The Navy did not have a formal aircraft designation system until 1922.

3. That aircraft is preserved in the National Air and Space Museum.

4. Rankin, “The Navy’s Schneider Cup Racers,” 806.