Such are the vagaries of history that some questions linger, some controversies rage on, evidence comes to light, opinions sharpen. It happens with many events, from the sinking of the Titanic to the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger. And so it is with the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941—the event that brought the United States into World War II. Although many aspects of the Pearl Harbor attack are well established, even now, 80 years on, there are pieces still in contention, decisions made (or avoided) still disputed. Here, we survey a few of those issues:

Kimmel

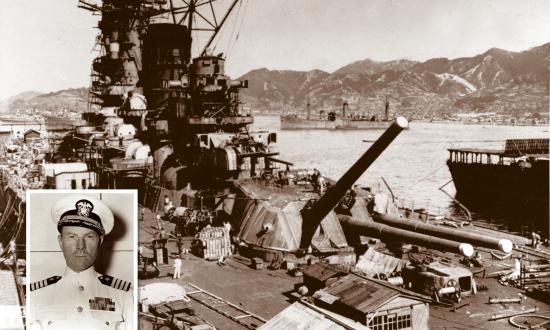

From the first moments after the Japanese attack, U.S. fleet commander Admiral Husband E. Kimmel became a marked man: Kimmel the scapegoat. The failure of readiness left five U.S. battleships sunk or crippled on the bottom of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the advanced base of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Someone had to be blamed.

Probably the thorniest matter for Americans looking back has been Kimmel’s treatment—whether it was justified, whether the admiral’s role should be re-evaluated, whether he should be accorded a more exalted place in the pantheon of U.S. naval officers. A recent retelling of this aspect of the story, Anthony Summers and Robbyn Swan’s A Matter of Honor: Pearl Harbor—Betrayal, Blame, and a Family’s Quest for Justice, centered precisely on the Kimmel controversy. The 2016 publication of this book should be regarded as a reflection of the new consensus on Admiral Kimmel.

A disaster of Pearl Harbor’s dimension had to have a culprit. The fundamental rationale for Kimmel shouldering the blame was that the Japanese strike force had taken the U.S. Pacific Fleet by surprise. Following the principle of command responsibility, Kimmel, the man in charge, was the obvious candidate. Another reason was political vulnerability: President Franklin D. Roosevelt, ultimately in charge, had no desire to take the blame and had ample means to slough it off onto Kimmel’s shoulders.

FDR also wanted to enter the war, and a Japanese attack offered a backdoor entry (about which more in a moment). A third factor in Kimmel’s scapegoating was the rush to judgment. There needed to be a quick explanation for the disaster. Within two days of the attack, on 9 December 1941, Navy Secretary Frank Knox began the first of many Pearl Harbor investigations, concluding there had been little readiness to resist from either the Navy or Army in Hawaii. The follow-up inquiry (18 December 1941–23 January 1942), led by Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts, linked the fault directly to the military commanders, Kimmel and Army General Walter C. Short.

In 1945–46, Congress held joint hearings to investigate the Pearl Harbor disaster. This was only the latest of the high-level inquiries that had begun with Secretary Knox’s visit. The probes took various positions on Kimmel’s responsibility, but in large part they denied him due process. The consensus continued to cast him as the rascal. Kimmel actually sought a court-martial, which he expected would exonerate him. Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, denied the request on the grounds that a controversial military court proceeding could disrupt the war effort.

Military and political aspects alike complicated the Pearl Harbor controversy. On the military side, by dint of tremendous creativity and application, Allied codebreakers had succeeded in breaking the Japanese diplomatic codes and could read what Tokyo sent its diplomats and attachés. Some Japanese naval codes had been solved as well, though changes made by the Imperial Japanese Navy had terminated complete access before the end of 1940, a condition the Allies labored to reverse. Either way, with minor exceptions Washington did not share the fruits of the codebreaking with its fleet commander.

Meanwhile, Pearl Harbor did have weaknesses as a naval base, ones that Admiral Kimmel recognized, but Washington had been slow to supply the additional guns, planes, and radars necessary to perfect the defenses. In the last fortnight before the attack, U.S. diplomats presented Japan with a set of unacceptable preconditions to further negotiations. Tokyo privately sent deadlines that then passed. Intelligence reported Japanese forces actually on the move. Tokyo instructed its embassies to destroy documents and codes, but Pearl Harbor was sent only a vague war warning. Washington issued no corrective when General Short responded he was preparing against local sabotage only.

On the political side, the Japanese attack pulled the United States into World War II—a boon to FDR, who had been looking for more ways to help the British but had been obstructed by isolationist sentiment in the United States. Events suggested a Rooseveltian conspiracy. This “back door to war” historical analysis was popularized by such historians as Charles Beard, George Morgenstern, Charles C. Tansill, and Harry Elmer Barnes. Holding Admiral Kimmel to account helped insulate FDR from such damning charges. As it happened, the Democratic Party of the time held the majority on the joint committee investigation, which meant the political shading favored protecting Roosevelt.

Husband Kimmel never could clear his name. His sons also failed. Walter Short did not even bother to publish a memoir. The battle lines were set with the congressional investigation. Later, such as in 1955, when Kimmel’s own memoir appeared, and in 1961, 1965, and 1981, at the 20th, 25th, and 40th anniversaries of Pearl Harbor, much public commentary followed the old scapegoating.

Ironically, the joint committee investigation also had uncovered the flaw in the original narrative—the fact that American codebreakers had been reading Tokyo’s messages. That Washington neglected to inform Pearl Harbor of the intelligence in a timely fashion put a damper on arguments of command responsibility. Much about the codes was revealed then. In the 1970s and after, detailed revelations about Japanese naval codes followed. The old consensus weakened. Something similar has happened with historical explanations of Japan’s decision for war with America.

Emperor and President

Among the more contentious aspects of Pearl Harbor’s received history are the roles of Japanese Emperor Hirohito, President Roosevelt, and British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill. In the conventional view, Hirohito lacked real power or authority; he opposed war with the United States, but his generals and admirals forged ahead regardless, according only lip service to the Emperor’s rejection. Japan lost the war, subsequently to be occupied by Allied forces under General Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur early decreed that Hirohito’s cultural and ceremonial role be preserved, continuing his imperial status, so the Emperor was never questioned, deposed, investigated, or held to account in any war crimes prosecution.

Leaving another rift in the history, contrasting visions persist of Hirohito as either passive figurehead or active decision-maker. A reflective message Hirohito recorded in 1946 (almost as an insurance policy against accusations of warmongering) asserted his opposition to war.

Many doubts spring from the fateful “imperial conferences,” Japan’s top decision-making forum. At one of these, on 6 September 1941, Hirohito famously pressed naval and military commanders to give diplomacy primacy over war plans. The Emperor read a favorite poem from his grandfather Meiji, extolling the latter’s love for peace, as a device to rein in current military leaders. Historians Herbert Feis and Robert J. C. Butow are the classic American interpreters of this event. Feis argued that the program accepted at this conference “could only mean war unless there was a reversal in the American attitude.” Both accepted that Hirohito resisted the march to war, though Butow was more conscious of conflicting possibilities.

In his 1961 study of General Hideki Tojo, prime minister in 1941, Butow wrote that the Emperor’s remarks of 6 September could have sprung “from a sudden and disturbing realization on his part of how dangerously close to war Japan really was, or . . . were motivated by a desire on the part of those close to the throne to place the Emperor on record in favor of peace so that he would be in the clear in case war came.” Feis and Butow’s depiction of Tokyo’s purposefulness bumps up against proponents of the “back door to war” thesis.

Journalist-cum-historian David Bergamini, born in Japan, was at work in 1967 on a massive inquiry into Tokyo’s role when the diary of Army Chief of Staff General Hajime Sugiyama was published in Japan. The source, ignored in the United States, reported Hirohito had a much more active role in Tokyo’s decision, including assigning naval officers to evaluate the feasibility of a Pearl Harbor attack.

The Bergamini history encountered a mixed reception. Since then, historians have taken both sides on the question of Hirohito’s responsibility. The Emperor’s 1946 oral history, published in 1990, records that the summer of 1941 oil embargo Roosevelt imposed (when Japan took over southern Indochina) cornered Tokyo. If Hirohito had tried to stop the militarists, then there would have been a coup d’etat.

Historian Noriko Kawamura, surveying this debate in a 2007 paper, concluded that Hirohito personally opposed war but was trapped within a nebulous power triangle, his court perspective tangling with that of the military, with the government suspended between the two. Kawamura credits Hirohito with delaying the onset of war by a month and a half. (In her later full-length study, she takes some of this back.) Here and also in the work of Eri Hotta appear the most recent twists from the Japanese side—the contention that middle-level officers at ministries and on general staffs exerted uncommon influence on top-level decisions.

On President Roosevelt’s side, debate has persisted virtually since the end of World War II. FDR passed away in April 1945 and could never explain his role. The argument centers on posture—was FDR sincerely attempting to preserve peace, or was he acting to goad Japan into striking the first blow (the back door to war)?

Attitudes on FDR, in turn, bear significantly on beliefs about the treatment of Kimmel and Short. The joint committee investigation and the other inquiries all featured participants angling one way or another to indict or protect Roosevelt. By the 1990s, around the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, historians and naval officers agreed widely that the source materials were politicized.

While enmity against the scapegoats seemed to dissipate, consensus failed to develop around their rehabilitation. In 1995, Under Secretary of Defense Edwin Dorn reviewed the disaster and reached an awkward conclusion: Responsibility for Pearl Harbor should be shared widely, but posthumous advancement to compensate for Kimmel’s harsh treatment would be inappropriate.

In 1999, the Senate passed an amendment to the Defense Appropriations Act recommending Kimmel and Short be exonerated and put this in an advisory to President William J. Clinton the following year. But Clinton left office without acting, and historians continue to dispute responsibility. At the 70th anniversary in 2011, Alan D. Zimm, in a well-regarded Pearl Harbor study, revived the charges against the hapless commanders.

JN-25

Had this pen been put to paper two decades ago, the best new data on codebreaking would have been from the work of Frederick D. Parker, a National Security Agency historian, who crafted several papers that shed new light on JN-25—the Japanese naval codes. Parker highlighted messages U.S. communications intelligence had intercepted in 1941 but had not had the time or energy to decrypt and translate until 1946, after the war was over. He argued the messages together provided incontrovertible evidence of a Japanese intention to attack Pearl Harbor. With the “gee whiz” glitz that attends many discoveries from intelligence research, the public made more of the new evidence than it deserved.

The Japanese messages concerned four subjects: Imperial Navy training for carrier air attacks, including against ships near or in base; a brace of items on shallow-running aerial torpedoes (Pearl Harbor is a shallow-water port); Japanese practicing at-sea refueling; and weather or maritime traffic reports on the northern Pacific.

These were suggestive indications, but they were not definitive, certainly not for a strike over the unprecedented distance of more than 3,300 nautical miles from Tokyo to Pearl Harbor. Both Singapore and Manila, though deeper than Pearl Harbor, were not that much deeper. North Pacific data would be important also for a campaign in the Aleutians, something Japan eventually undertook. Refueling at sea would be critical to any long-range operation, and it was something the U.S. Navy also was working to master.

The question of who would put all the indicators together was critical. By 1946, analysts were practiced at this. In 1941, no one was, and there were practically no analysts. Dicey no matter how you cut it.

The 1946 decrypts were less important for their direct evidence on Pearl Harbor than for the opening they provided to reexamine classic disputes. British author James Rusbridger, teamed with former Australian codebreaker Eric Nave, used these decrypts to argue that British and U.S. signals intelligence units were reading the Japanese naval codes throughout the period. They developed a betrayal theme and applied the “back door to war” thesis to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Numerous gaps in evidence and logic led most observers to dismiss Rusbridger and Nave’s thesis. Churchill, who actually spent the day of 7 December 1941 at his country estate Chequers, closeted with Americans W. Averell Harriman and John G. Winant, learned of Pearl Harbor from his butler. Churchill would have been astonished by the Rusbridger-Nave claim that he had deliberately suppressed intelligence intercepts revealing Japanese intentions.

A 1999 study from American author Robert Stinnett also advanced the backdoor argument, asserting not just that FDR had sought to draw Japan into war, but also that he had relied on a subordinate naval officer, Commander Arthur H. McCollum, heading the Japan desk of the Office of Naval Intelligence, and followed a strategy McCollum had articulated in a 1940 paper.

The fact that no evidence shows FDR actually saw this paper is consonant with other flaws in Stinnett’s presentation, among them the claim the Americans were reading the Japanese naval code before Pearl Harbor. The appearance of the 1946 decrypts has had a deleterious effect on our understanding of the history.

Admiral Kimmel’s best argument was, and remains, that Washington kept him in the dark about what it knew of Japanese intentions. This is true, and it has everything to do with preserving the secrecy of codebreaking. The Americans and British were reading the Japanese diplomatic codes and, for a time, the naval code, which they were working to reacquire.

Kimmel repeatedly asked to be told what Washington knew of Japanese plans. Only once—in July 1941—did the Navy supply its fleet commander with information drawn from its decrypts. In late November, Washington sent a war warning, but it was one based primarily on the sorry state of U.S.-Japanese negotiations, which Hawaiian commanders interpreted as a signal to look out for sabotage or subversion, not an air raid from a carrier fleet. The executive revealed the fact of the codebreaking in late 1945, during the congressional investigation of Pearl Harbor, and released hundreds (of the thousands) of messages involved.

The ostracization of the Hawaiian commanders to protect FDR and the codebreakers ought to have ended there. Instead, even though a succession of revelations over the years brought the codebreaking into sharper focus, this brought no end to the Pearl Harbor debate.

Remembered . . . and Honored

Each year, a contingent of veterans gathers to commemorate Pearl Harbor Day. But that contingent grows ever smaller, and presently, the commemorations will lose this human link to the real events.

rest with his shipmates, a salute to the battleship memorial’s wall of names is in order. As the World War II generation fades away, the echoes of Pearl Harbor continue to resonate. Credit: DVIDS

But the Date Which Will Live in Infamy should still be honored—not just for the brave sailors who perished there, or the lessons Pearl Harbor has to teach, but also for its example for new generations of presidents and naval commanders, whose responsibility to our sailors remains undiminished.

Sources:

Harry E. Barnes, Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace (Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1953).

Charles A. Beard, President Roosevelt and the Coming of War, 1941 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1948).

David Bergamini, Japan’s Imperial Conspiracy (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1971).

Robert J. C. Butow, Tojo and the Coming of the War (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1961).

VADM George C. Dyer, USN (Ret.), On the Treadmill to Pearl Harbor: The Memoirs of Admiral James O. Richardson (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, Naval Historical Division, 1973).

Ladislas Farago, The Broken Seal (New York: Random House, 1967).

Herbert Feis, The Road to Pearl Harbor: The Coming of the War Between the United States and Japan (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1950).

Michael Gannon, Pearl Harbor Betrayed: The True Story of a Man and a Nation under Attack (New York: Henry Holt, 2001).

Eri Hotta, Japan 1941: Countdown to Infamy (New York: Knopf, 2013).

Noriko Kawamura, “Emperor Hirohito and Japan’s Decision to Go to War with the United States: Reexamined,” Diplomatic History 31, no. 1 (January 2007): 51–79.

Noriko Kawamura, Emperor Hirohito and the Pacific War (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015).

Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, Admiral Kimmel’s Story (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1955).

George Morgenstern, Pearl Harbor: The Story of the Secret War (New York: Devin-Adair, 1947).

Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 3, The Rising Sun in the Pacific (Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1948).

Kevin O’Connell, Pearl Harbor: The Missing Motive (North Charleston, SC: Create Space, 2015).

John Prados, Combined Fleet Decoded: The Secret History of American Intelligence and the Japanese Navy in World War II (New York: Random House, 1995).

Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981).

Gordon W. Prange, Donald M. Goldstein, and Katherine V. Dillon, Pearl Harbor: The Verdict of History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1986).

James Rusbridger and Eric Nave, Betrayal at Pearl Harbor: How Churchill Lured Roosevelt into World War II (New York: Summit Books, 1991).

David E. Sanger, “In a Memoir, Hirohito Talks of Pearl Harbor,” The New York Times, 15 November 1990.

Robert Stinnet, Day of Deceit: The Truth about FDR and Pearl Harbor (New York: Free Press, 1999).

Anthony Summers and Robbyn Swan, A Matter of Honor: Pearl Harbor—Betrayal, Blame, and a Family’s Quest for Justice (New York: Harper-Collins, 2016).

Charles C. Tansill, Back Door to War (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1952).

John Toland, Infamy: Pearl Harbor and Its Aftermath (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1982).

U.S. Congress, 79th Congress, 1st Session, Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack, Hearings, Exhibits, Reports (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1946).

Alan D. Zimm, Attack on Pearl Harbor: Strategy, Combat, Myths, Deceptions (Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers, 2011).