When Sir John Barrow took up the position as Second Secretary of the Admiralty of the United Kingdom in 1804, he inherited a legacy of European naval exploration that spanned back centuries. During his 41-year tenure in his position, Barrow advocated for the discovery of a Northwest Passage over Canada, providing an efficient means traveling from the Atlantic to Pacific Oceans. Over the ensuing decades various noted explorers, including the famed William Edward Parry, set off for the Canadian Arctic in an attempt to map its myriad mysteries.

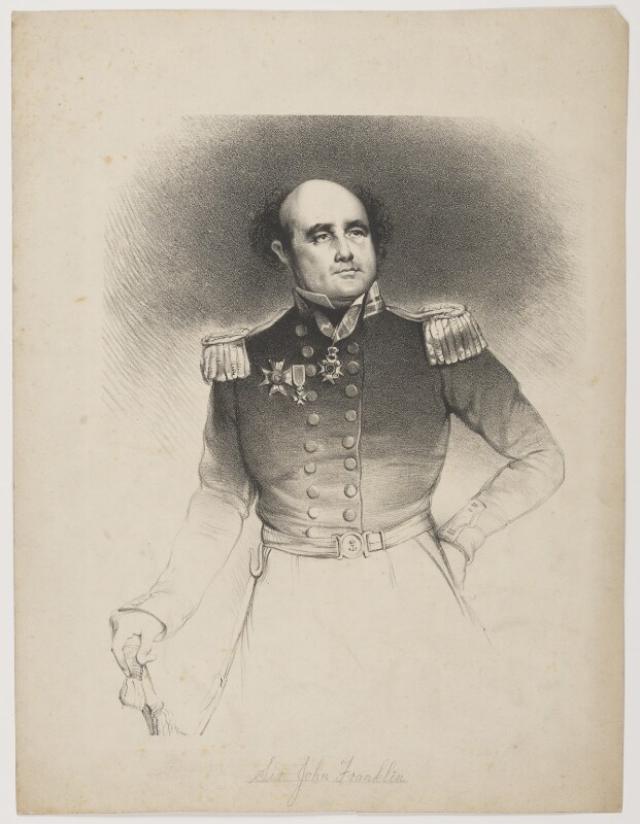

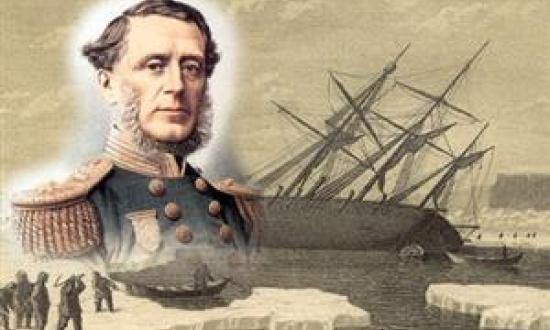

One such explorer, Royal Navy officer Sir John Franklin, found himself on several of these expeditions. In 1818 he served as second-in-command of an expedition in the area on board the ships Dorothea and Trent, and went on to lead two further expeditions in 1819–22 and 1825–27. By the time he was selected to lead yet another expedition in 1845, Franklin was no stranger to the treachery that lay ahead of him and his crew. But little did he know that he was about to set off on what would become one of history’s greatest maritime mysteries.

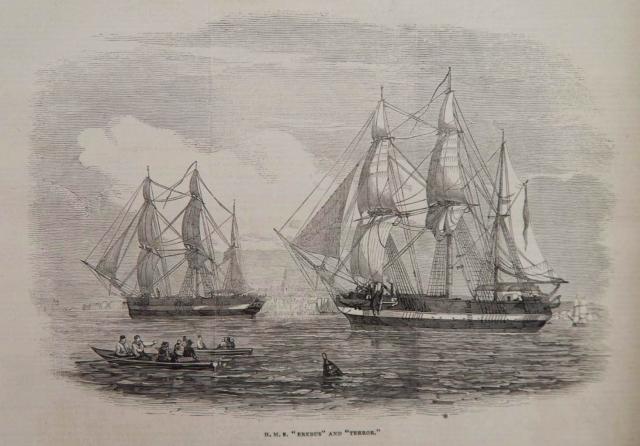

Franklin was not Barrow’s first choice to lead the expedition, not by a longshot. Barrow, who at the time was 82 years old and nearing the end of his career, approached five individuals for the job before eventually settling on Franklin.1 The expedition was to be composed of two ships: the Hecla-class bomb vessel HMS Erebus (1826) and the Vesuvius-class bomb vessel HMS Terror (1813). Franklin was given command of the Erebus and two of Barrow’s prior candidates for the role of expedition leader were appointed to other high-ranking positions in the expedition. The Irish-born explorer and naval officer Francis Crozier was given command of the Terror, and the young naval officer James Fitzjames was appointed second-in-command of the Erebus.

Like the man who was to lead the fateful expedition, the ships themselves were also well acquainted with the exploration of frigid waters, having both been used in James Clark Ross’ 1841–44 Antarctic expedition. Each of the ships were fitted with “reinforced bows for cutting through ice and iron rudders that could be pulled into heavy iron wells if the situation necessitated it”.2 The Erebus and Terror also were fitted with an internal steam heating system to keep their crews reasonably comfortable amid the harsh conditions of the Canadian Arctic. Structurally, both ships were considered hearty cold-weather vessels.

Franklin reportedly was quite proud of the preparations he made for the journey.3 The ships featured a library of more than 1,000 books for the officers and crew to enjoy throughout their voyage. Instead of settling for the typical rations of salted pork and other dry goods, Franklin opted to contract Stephen Goldner, a provisioner with access to then state-of-the-art tinning technology, to prepare 8,000 tins of food meant to last for around three years. However, the contract with Goldner was drawn up and finalized on 1 April 1845, only seven weeks before Franklin’s expedition was set to depart.4 As a result of this restrictive time frame, Goldner worked hastily to fill the order and was reported to have sacrificed a great deal of quality control in the process. Upon the eventual discovery of the remains of the expedition, the tins were found to have been sloppily sealed with lead soldering, which dripped into the contents of the tins.5

Franklin’s expedition set sail from Greenhithe, Kent, on the morning of 9 May 1845. The ships first traveled to Stromness, Orkney Islands, in northern Scotland, and then to Greenland with the help of HMS Rattler and the transport ship Baretto Junior. Upon reaching Greenland’s Disko Bay, more provisions were gathered and the crewmen on board the Terror and Erebus sent what would be their final letters to their loved ones back home. During this stop, five men were discharged, reducing the final number of personnel in the expedition to 129. The final sighting of the expedition by Europeans took place in late July 1845, when the whalers Prince of Wales and Enterprise spotted the Terror and Erebus in Baffin Bay, waiting for conditions to improve enough for safe passage across Lancaster Sound.6 After the encounter in Baffin Bay, the Terror and Erebus, along with the 129 souls on board, were never heard from again.

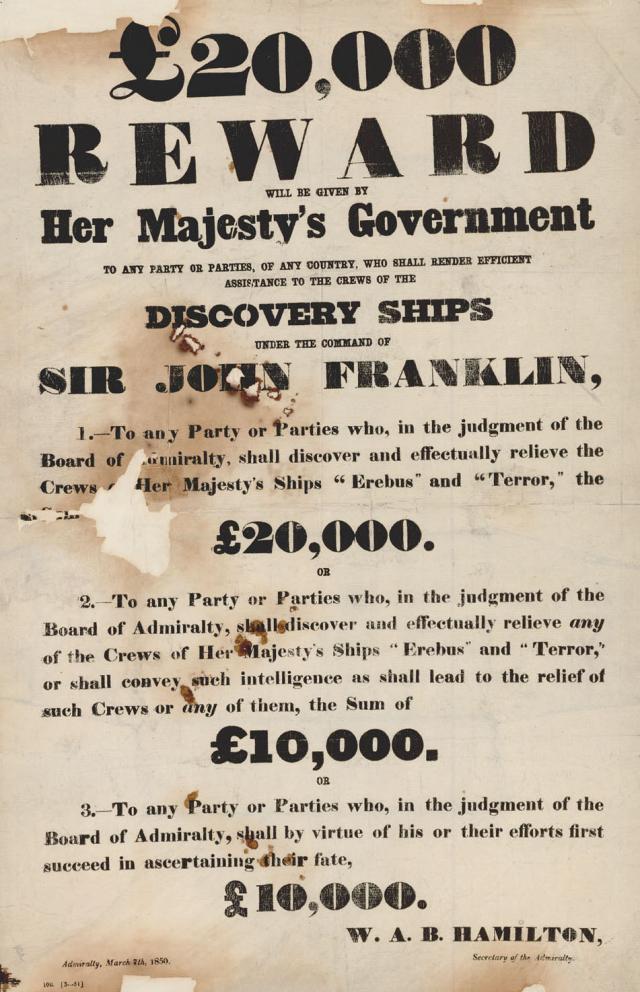

Of course, this expedition was meant to take quite some time under the best of circumstances. As such, alarm bells were not officially sounded for two entire years following the expedition’s departure. Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin, along with some members of Parliament and other influential entities began to pressure the Admiralty to send out search parties for the missing men. In spring of 1848, the first overland search party was dispatched, marking the start of what would become a 150-year effort to discover the fate of the lost Franklin expedition.

Group after group set out to unlock the mysteries of this ill-fated voyage, with some 32 separate expeditions taking place between 1849 and 1859.7 An 1850 search expedition to Beechey Island turned up the first traces of the lost expedition. An abandoned camp from the winter season of 1845–46 was discovered, along with something far more gruesome.

The graves of three men, Petty Officer John Torrington, Royal Marine Private William Braine, and Able Seaman John Hartnell, all members of Franklin’s expedition, were unearthed near the site. No other information regarding the further movements of Franklin’s expedition were discovered at that time.

In the years following the 1850 search, European and American search parties often turned to the local Inuit population for help in locating the lost men. Some individuals had come into possession of items determined to have belonged to members of the Franklin expedition, while others told stories of foreigners starving to death along the coast.8 On 31 March 1854, Britain officially declared the crews of the Terror and Erebus deceased and decided to dispatch no further search parties.

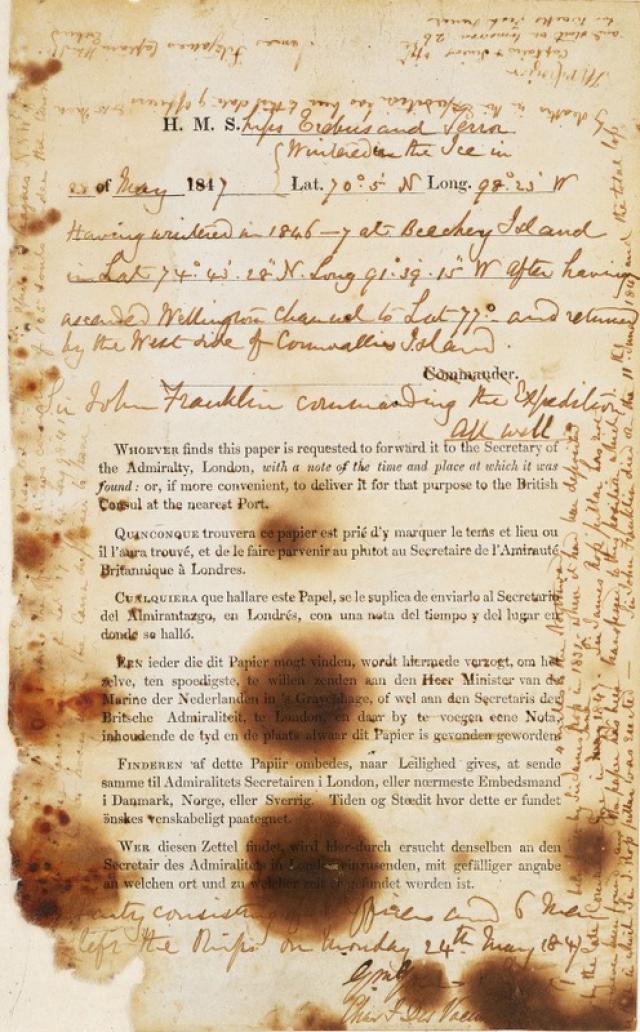

Despite Britain’s official decision, Lady Franklin collected enough money to dispatch another, private search, this time on board the schooner Fox. This search expedition departed England in 1857, and in 1859 it discovered one of the most ominous clues yet. During an overland search of King William Island, a cairn was discovered. In it was a document containing two messages left by Crozier and Fitzjames. The first message, dated 28 May 1847, bore good news. The ship had “wintered in 1846–7 at Beechey Island,” and “Sir John Franklin commanding the Expedition. All well.”9

The second message, dated 25 April 1848, painted a much grimmer picture. Twenty-four of the expedition’s members, including Franklin, had died by 11 June 1847, a mere two weeks after the first message had been written. The note explained that surviving 105 men were going to head south toward the Back River under the command of Crozier.10 One more set of skeletal remains determined to have been a member of the Franklin expedition was discovered by the Fox party.

As the years and decades dragged on, more and more traces of the Franklin expedition were uncovered. Additional gravesites, relics, and oral testimonies of the local Inuit population painted a bleak picture of starvation, sickness, and desperation. Archaeological excavations and exhumations at Beechey Island and King William Island in the 1980s and 1990s only solidified the tragic fate of the Franklin expedition. Vitamin C deficiencies ultimately leading to scurvy were detected in the remains of many of the men, and skeletal patterns commonly found in cases of cannibalism were noted on several bones unearthed at the gravesites.11 High concentrations of lead also were discovered in many of the remains, though it is unclear whether it came from the aforementioned tinned food or from the ships’ water distillation systems. Evidence of pneumonia, tuberculosis, and Pott’s Disease also were noticed in some of the remains.

Though many discoveries had been made until this point, two huge pieces of the puzzle were yet to be found: the Erebus and Terror. The discovery of the wrecked ships would not come until 2014 and 2016, respectively. On 1 September 2014, two pieces of a Royal Navy vessel were found on Hat Island in the Queen Maud Gulf near Nunavut's King William Island.12 A few days later, on 7 September, the team working in the area announced the official discovery of the Erebus submerged in around 36 feet of water in the eastern portion of Queen Maud Gulf. Almost exactly two years later, on 16 September 2016, the Arctic Research Foundation announced the discovery of the Terror, submerged in around 79 feet of water in Terror Bay, just south of King William Island.

While the exact narrative of the Franklin expedition is lost to history, over a century of dedication to the historical record has allowed us a glimpse at the hardships these 129 souls faced in their quest for discovery. The officers and crew battled against freezing temperatures, malnutrition, disease, lead poisoning, and even cannibalism before eventually succumbing to the insurmountable odds. Thanks to the perseverance of countless explorers, local Inuit groups, and archaeologists, the mystery of the lost Franklin expedition can finally be put to rest.

1. Martin Sandler, Resolute: The Epic Search for the Northwest Passage and John Franklin, and the Discovery of the Queen's Ghost Ship (New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 2006), 65–74.

2. “Captain John Franklin’s Lost Expedition: The History of the British Explorer’s Arctic Voyage in Search of the Northwest Passage” by Charles River Editors, Chapter 1.

3. Charles River Editors, Chapter 1.

4. Owen Beattie and John Geiger, Frozen in Time: Unlocking the Secrets of the Franklin Expedition (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1987), 25, 158.

5. Beattie & Geiger 1987, 113.

6. Richard Cyriax, Sir John Franklin's Last Arctic Expedition; a Chapter in the History of the Royal Navy (London: Methuen & Co., 1939).

7. James P. Delgado, “Toward No Earthly Pole,” Naval History, vol. 18, no. 2 (March-April 2004).

8. Cyriax, Richard (1939).

9. “The Note in The Cairn (transcript),” NOVA.

10. NOVA: “Arctic Passage—The Note in the Cairn (transcript)”.

11. Beattie & Geiger 1987, 58–62.

12. CBC News, “Franklin Expedition Ship Pieces Believed Discovered in Arctic.”