Expediency, especially in time of war, often fosters stopgap measures that seldom provide perfect solutions. At times, however, they prove to be just what was needed. Such was the case during the Civil War on the Western waters. After the initial river battles in the first six months of 1862, the Union had gained control of the Ohio, Tennessee, Cumberland, and upper Mississippi rivers, but the U.S. naval force of just nine ironclads and three wooden gunboats could not maintain control over such a large area. The heavy ironclads were needed at Vicksburg, leaving just the Lexington, Conestoga, and Tyler farther north.

On 28 June 1862, Acting Flag Officer Charles H. Davis of the Western Gunboat Flotilla requested that Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles purchase a new type of gunboat. The boats, of shallow draft, “will be sufficiently protected about the machinery and pilot houses against musketry” and have the capacity for “a suitable armament of howitzers, fieldpieces, or other light guns.”

The Navy termed the 76 ships soon acquired “tinclads,” or “light drafts,” although tinclad was a misnomer. The name reflected their thin iron armor, which in some instances was not iron at all, but simply wooden bulwarks. The gunboats had a variety of sources; most were former commercial riverboats, some were purchased or confiscated, and still others were captured Confederate vessels.

While they were of no homogeneous design, they were somewhat similar in size—about 150 feet long with a draft of two to six feet and a burden of about 200 tons. All were similarly modified at Cairo or Mound City, Illinois. In general, the gunboats had two decks, the main and hurricane, with an armored box-like pilothouse on top. The main deckhouse was enclosed in a wooden casemate, and sheets of boiler iron, usually 1/2 to 1 inch thick, were mounted on the forward casemate and around the boilers. The tinclads’ weapons were as varied as their designs, most often 12- or 24-pounders on the broadsides and a pair of heavier 32-pounder smoothbore or 8-inch rifles in the bow.

By August 1862, the first of the tinclads was in action on the Ohio and the Tennessee. In addition to patrolling the waterways, the vessels often were used as troop transports; they had much greater access to shallower and narrower tributaries than did the heavyweights that preceded them.

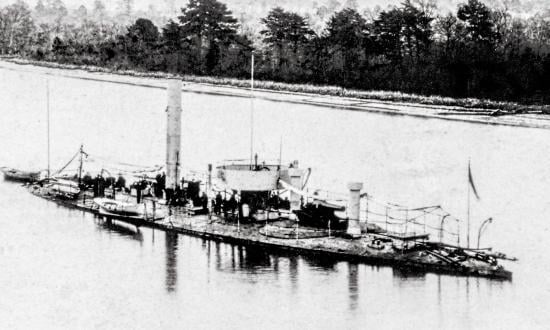

There was no typical tinclad; each was unique in some manner, and such was the case with “Tinclad” Gunboat No. 1, the Rattler. She originally was built as the stern-wheel steamer Florence Miller at Cincinnati in 1862. Nothing specific is known of her physical dimensions, although an existing photograph shows her to approximate those cited above. The Navy apparently bought her as a new ship on 11 November. She was renamed on 5 December and commissioned exactly two weeks later at Cairo. It was not long before she was in combat under command of Lieutenant Commander Watson Smith.

On 10 January 1863, Acting Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter’s Mississippi Squadron, with the Rattler at the point as the tinclad first division leader, ascended the White and Arkansas rivers to attack Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post in a joint Army-Navy expedition. The Rattler saw heavy combat, and Porter wrote in his after-action report the ship “suffered a good deal” with her cabins “knocked to pieces.” “Strange to say, two heavy shell struck [the] iron plating [3/4-inch] on the bow and never injured it.” In a later report, Porter elaborated that he ordered plating on the pilothouses and casemates to be covered in tallow. The Rattler was “struck fair” on her plates by two IX-inch shells, which “flew upward without scratching the iron. . . . She was knocked into a cocked hat, but got by.” Despite the damage, the gunboat lost only two men.

From 11 to 13 March during the Yazoo Pass expedition, the Rattler once again led her division of tinclads. Two of the heavily armored ironclads leading the assault on Fort Pemberton were mauled, and the Northern forces withdrew.

Through the summer, the Rattler participated in raids up the Red, Black, Tensas, and Ouachita rivers. On 13 July, she and the tinclad Manitou captured the Rebel steamer Louisville on the Little Red River. Patrols based around Rodney, Mississippi, below Natchez, continued until 13 September, when the ship’s history first turned strange. Porter reported to Welles “the capture by guerrillas of Acting Master W. E. H. Fentress, 1 officer, and 15 men, consisting of the best men in the vessel. He was captured while at church.”

The Rattler’s Acting Yeoman James R. Hewlett wrote years later: “Capt. Fentress, feeling secure under [the Rattler’s] protecting guns” decided to attend church services. As his orderly, Hewlett was helping the captain off the ship’s gig when he slipped in the mud. Fentress ordered him back to the ship to clean up. “While doing so the 1st Ark. Cav. made a raid on the church.” Hearing the commotion, “we shelled church, town, and vicinity.” Fentress was sent to Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, and the others to Andersonville, Georgia.

Fentress had been warned by his superior officer about his trips ashore, especially to Rodney. Subsequent correspondence from Porter is rife with invectives for the Rattler’s commander. “I will omit nothing to have him dismissed [from] the service.” Fentress begged Porter for forgiveness and a return to his command in a 15 November 1863 letter from Libby Prison. “My treatment since my capture has been brutal; but inhuman as it is, sir, I would be happy if I knew that your displeasure was removed and that I might again retrieve my character in the Mississippi Squadron, under your command.” There is no copy of Porter’s response.

After this incident, the gunboat patrolled the river near Rodney for more than a year.

Hewlett described a second bizarre incident, on 4 September 1864, after the Rattler was hailed from ashore and the crew informed that “some” Rebel officers were visiting a plantation near Carthage Bayou, Louisiana. A volunteer party was raised to capture them. “I with them, went ashore to find [Colonel Isaac F.] Harrison’s Brigade of Cavalry, 2,700 strong encamped on the James plantation, but instead of capturing, we ourselves were captured.” Twenty of the Rattler’s crew were taken; the officer in charge and two men escaped.

The gunboat’s commander, Acting Master Daniel W. Glenney, had authorized the venture. The next morning, he and a party went ashore some 20 miles inland under a flag of truce to negotiate parole of his crew. This was done, and once the sailors had been returned on 6 September, Glenney left his ship and reported to Lieutenant Commander Thomas O. Selfridge, Fifth District commander on board the Vindicator. The next day, Glenney passed upriver on board the steamer Empress, bound for Vicksburg. He hailed the Rattler and ordered the executive officer to allow no one ashore, keep vigilant for Rebels in the vicinity, and “fire a shell every fifteen minutes or thereabouts during the night.” Glenney returned to his ship on 10 September.

In a letter to Porter, Selfridge wrote: “The strangest part of the story is that the enemy went off in the Rattler’s cutter to capture her. They were only discovered within musket range, and but for an accident would have been on board of her.” There also was no explanation of Glenney’s unauthorized trip. On 11 September, Glenney was placed under close arrest on board the Rattler. Subsequent investigation revealed that as early as May 1863, through intermediaries, his proposal to sell a U.S. Navy gunboat to the Confederacy had made it through channels to the desk of President Jefferson Davis. Glenney had an agreement with Harrison to have a portion of his crew captured to weaken her defenses and then to have his ship overpowered by Harrison’s men. He was to receive $2,000 and 100 bales of cotton. On 4 November, he escaped with the aid of his executive officer, Acting Ensign E. P. Nellis; both were labeled deserters.

In a correspondence after the escape, Union Rear Admiral Samuel P. Lee wrote that Glenney went to New Orleans, where he was assisted by Confederates to enter Mexico “and has not since been heard from.” There are no records of a court-martial.

On 30 December 1864, during a heavy gale near Grand Gulf, Mississippi, the Rattler began dragging an anchor despite the ship being under full power. She struck the supply steamer Magnet, which swung the gunboat broadside to the wind. The Magnet parted her chains and was driven ashore. Before the tinclad could turn into the wind, her chains parted and she also was driven ashore, where she struck a snag, which stove in her port side amidships. The Rattler sank within five minutes. Her men and all but her two 30-pounder Parrotts were removed to the Magnet, which had freed herself from the grounding. Rebel forces almost immediately set fire to everything above water.