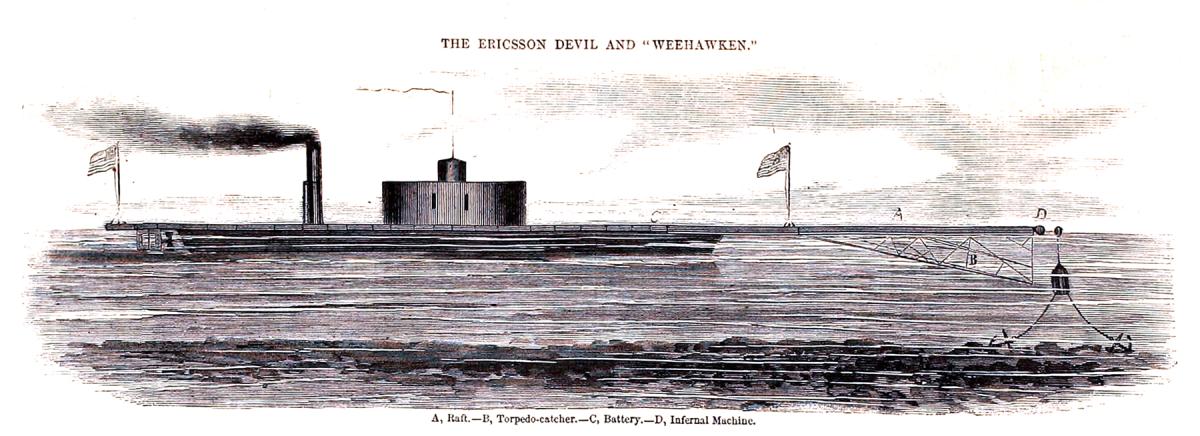

As the Union Navy moved into position to attack the blockaded Confederate port of Charleston, South Carolina, in the spring of 1863, it did so with some trepidation. While the Navy would be using its new ironclad ships in a large massed force, it found the threat of Confederate obstructions, particularly “torpedoes”—known today as mines—especially troubling. The service searched for an effective countermeasure to these “infernal machines.”

On 24 October 1862, Swedish-American inventor and engineer John Ericsson—the genius behind the USS Monitor—wrote to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Vasa Fox concerning the removal of obstructions from a “certain Southern city.” He said he could devise a “butting” raft for his monitors to destroy the impediments. The Navy gave him a contract, and by early 1863 he had completed a “minesweeper” for attachment to a monitor’s bow. While it was officially called the Ericsson Obstruction Remover, it soon became better known in Southern circles and the Northern press as Ericsson’s Devil.

J. M. Caiella

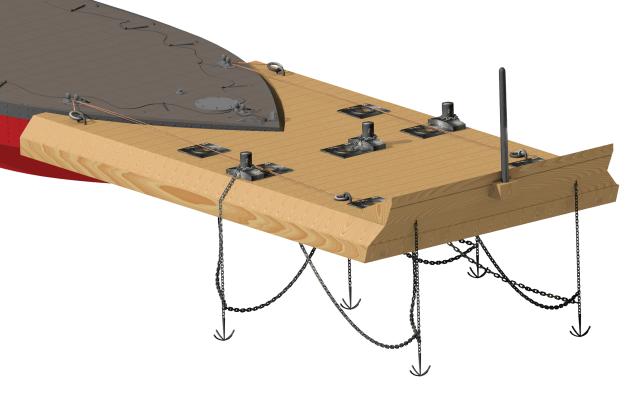

The device was simple in concept and design. It was a rectangular raft, approximately 50 feet long and 27 feet wide with a 20-foot-long V-notch in its stern to accommodate the bow of a monitor. The raft consisted of two layers of 18-inch-square white pine timbers securely fastened to each other by long, thick iron bolts, with a layer of beveled timbers at the front forming a bow. The structure was attached to the monitor by chains and rope lashings.

At the raft’s bow were a pair of booms that raised and lowered a heavy “bottom scraper” beam, which could extend 12 feet below the waterline. With a monitor drawing eight to ten feet of water, the scraper guaranteed nothing untoward would get under the ship. A series of iron bars parallel to the beam connected the booms, forming a network to catch intermediate objects. Attached to the beam was a pair of “submarine shells,” each 11½ feet long, 10 inches in diameter, and containing 350 pounds of powder. When hazards were encountered—whether torpedo or barrier—the shells were to be lowered and exploded to destroy the Rebel structure. A “trigger board”—contact fuse—detonated them. Copper air chambers between the explosives and trigger board would direct the force of the blast.

Alban C. Stimers, chief engineer of the U.S. Navy, conducted an experiment in New York Harbor to verify the safety of the monitor and raft in the wake of the shells’ detonation. He “proved how impossible it was” for the explosions to sink or severely damage the monitor.

On 30 January 1863, the steamer Ericsson left New York with four rafts in tow and a load of submarine shells, bound for Fortress Monroe at Hampton Roads, Virginia. One raft was lost in a storm the first day out. On 10 February, the steamer departed Virginia, now bound for Port Royal, South Carolina, about 75 miles southwest of Charleston. Two days later, in a gale in the dead of night, two of the three remaining rafts broke away and were lost, some 40 miles south-southwest of Cape Hatteras. The Ericsson arrived in Port Royal on the 18th with just one raft in tow. Stimers, who arrived later and was put in charge of the Ericsson, raft, and shells, requested another raft in mid-March, and at least three were later delivered.

Trials with the raft were conducted on the North Edisto River, where, according to Stimers, the Passaic-class monitor Weehawken steered better with the raft attached than without. Her commander, Captain John Rodgers, disagreed but was willing to take the raft into battle when his fellow captains were not. Rodgers was skeptical of the submarine shells, however, and fearing damage to his ship or others, had them removed and replaced by grappling hooks suspended by chains below the raft.

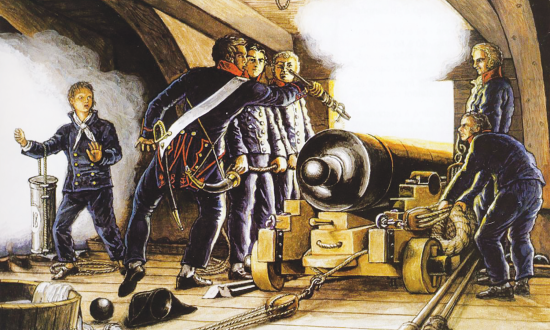

As the ironclad fleet prepared to battle Charleston’s defenses on 7 April 1863, one of the grappling hooks snagged the Weehawken’s anchor chain, causing an almost two-hour delay in the attack. As the fleet prepared to attack, the chains and lashings retaining the raft broke twice in quick succession as the Weehawken crossed over Charleston Bar into the anchorage. Once inside, the sea “converted the raft into a huge battering ram, which shook the vessel at every undulation.” The 90-ton appendage pitched completely out of phase with the ship. In his after-action report, Rodgers wrote, “The raft rose while the vessel fell, and the reverse. It was a source of apprehension lest it should get upon the deck or under the overhang.”

Once the interaction of raft and monitor had begun to damage the ship’s five inches of iron bow plating, Rodgers cut the raft adrift. The abandoned Devil floated for a day before washing ashore on the Morris Island beach, falling to the Confederates.

Rodgers’ fears about the shells proved prescient. During the battle, the Weehawken nearly collided with the ironclad New Ironsides—and two other monitors did collide with her. Had the raft been carrying the shells, the result could have been disastrous.

The battle went poorly for the Union forces, and the ironclad Keokuk was sunk. But she remained recoverable in fairly shallow water, so Rear Admiral Samuel Francis DuPont, commander of the squadron off Charleston, ordered her destruction. Rodgers volunteered to use the one remaining raft towed by the Ericsson. Heavy seas forced the abandonment of the transfer, but once the sea calmed, monitor and raft were joined and the shells were put in place. However, the engineer sent down from New York to set the charges and trigger could not do so because the water was still too rough and the spray prevented his work.

Eventually, Stimers reported that all was ready, but when Rodgers made a final inspection, he found that 24-inch-long, 5-inch ringbolts had pulled out of the raft and left it in such a state that it could swing around and strike the monitor. A restraining chain was rigged, but Rodgers “had no faith” that the chain would survive. “All sailors know from experience that chain is less reliable against surges than lashings.” The attempt was abandoned, as was the Keokuk and—more important—her two XI-inch Dahlgren guns. The Confederates recovered the valuable weapons.

Three rafts remained at Port Royal, and on 6 November 1863, trials were conducted with one attached to the Patapsco, another Passaic-class monitor. The raft was fitted with a single shell, 23 feet long and 10 inches in diameter, filled with 600 pounds of powder. The shock of the explosion lifted the raft about two feet off the surface and threw a large amount of water 40 to 50 feet in the air, but it was barely felt in the monitor. Although the Patapsco’s captain was certain the Devil would work, the difficulty of navigation, the movement between the raft and monitor, and the complicated nature of deploying the shells restricted its utility. The rafts were never deployed.

Three years after the war, in 1868, an Ericsson raft was found floating offshore at St. David’s Island, Bermuda, where it was towed into Dolly Bay. Although its salvors wanted to reclaim its wood, the heavy, thick bolts holding it together forced them to abandon it. In 1872, Captain Edward Faucon, who had commanded the Ericsson when she towed the rafts to South Carolina, saw the remains and recognized it as one of those lost on the voyage. Remnants of it have been preserved in a local museum and in the Naval History and Heritage Command’s artifact collection.

Another possible—and more surprising—raft was discovered in the wake of Hurricane Allen in 1980 at Mustang Beach, Texas, where three sections of a massive bolted timber structure were found. Remains of the Weehawken’s raft, which was recovered by the Confederates, can be found today in the marsh on the south bank of Bass Creek on the backside of Morris Island, near Charleston.