A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, Version 2.0—Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John C. Richardson’s strategic plan for the U.S. Navy—has the desired end state of a “naval force that produces outstanding leaders and teams, armed with the best equipment, that learn and adapt faster than our rivals . . . [and] will maximize their potential and be ready for decisive combat operations.”1 To do this, Design maintains a focus at the strategic level, pursuing lines of effort to develop new platforms, better weapons, and well-trained warfighters.

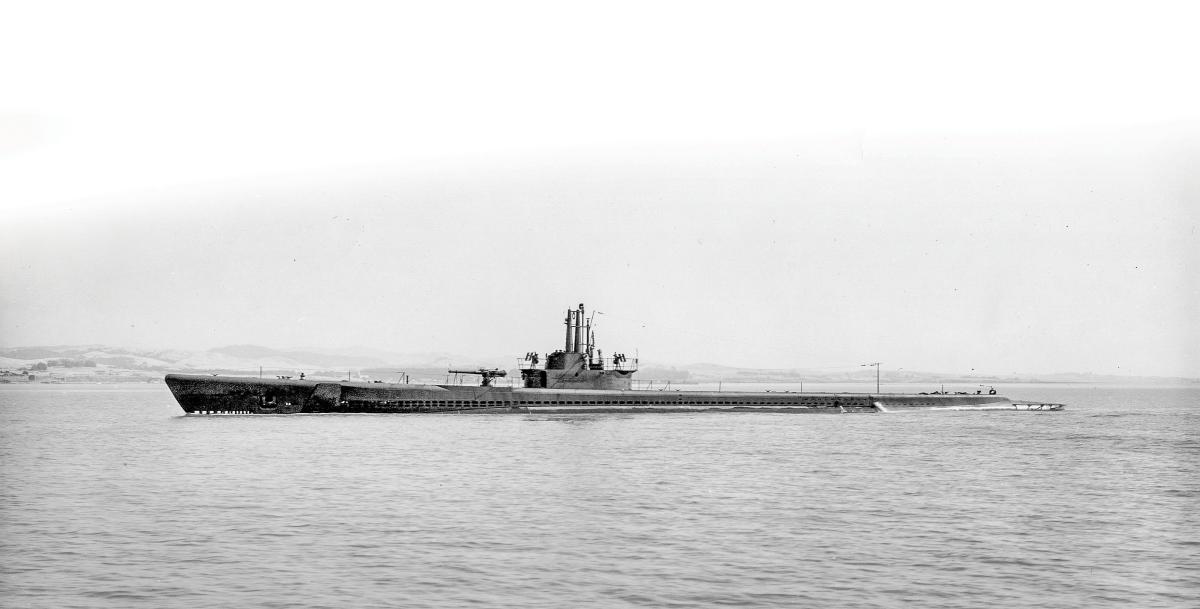

But what do outstanding leaders and teams look like? One case from the U.S. Navy’s submarine force during World War II answers this question: the Balao-class submarine USS Seahorse (SS-304), and her most successful commanding officer (CO), Captain Slade D. Cutter. Under Cutter’s command, the Seahorse sank 19 ships and earned the Presidential Unit Citation.2 The story of Cutter and the Seahorse provides valuable models of leadership, mentorship, and teamwork that should be internalized at all levels in the Navy.

Because of his background in music and sports, Cutter epitomized team-oriented leadership. He benefited from mentors who thoroughly trained him and also protected him from poor leaders—and himself. And under Cutter’s training, the Seahorse’s crew bonded into a strong team whose talents were best matched with the ship’s needs. Cutter and the Seahorse exemplify the outstanding leaders and teams necessary for U.S. maritime superiority.

A Team-Oriented Leader

Slade Cutter showed an early appreciation for teamwork. Despite his imposing size, his father prohibited him from playing contact sports throughout his childhood. Cutter turned to music, winning a national flute championship in 1928. He credited his victory to his talented accompanist, a sign of both his personal humility and his belief in teamwork.3

That commitment to teamwork only grew at the U.S. Naval Academy, where Cutter played fullback, center, tackle, and kicker under the mentorship of Navy football coach Rip Miller. During his senior year, Cutter soared to fame during the 1934 Army-Navy game, when he scored a first quarter field goal. The three points ended up being the only points of the game; because of Cutter, Navy won its first Army-Navy game in 13 years. He characteristically credited “75 percent” of the kick to his holder.4

As an officer, Cutter grew concerned that his peers saw him only as a jock. During two years on board the USS Idaho (BB-42), he coached the battleship’s athletic teams, winning fleet championships. He then served as assistant coach at the Naval Academy before attending submarine school in New London, Connecticut. Even after submarine school, he returned to coaching at the Academy while simultaneously serving in the USS S-30 (SS-135), which was assigned to Annapolis to indoctrinate midshipmen in submarine warfare. Just when it seemed he would never escape the playing field, he reported to the USS Pompano (SS-181) in December 1938.5

Mentorship: Parks, Lockwood, and Brown

On board the Pompano, Cutter immersed himself in an intensive qualification regimen about submarine tactics, engineering, and weapons. Cutter’s CO in the Pompano, Lieutenant Commander Lewis S. “Lew” Parks, expertly oversaw this demanding apprenticeship. Parks taught Cutter mental tricks to conduct submerged approaches without the use of aids, as well as other highly advanced skills.

Although submarine officers were supposed to qualify in one year, Parks delayed his officers’ qualification boards for more than two years before asking the submarine division commander to ride in the Pompano and observe his junior officers in action. One-by-one, Cutter and two other officers conned the submarine through a submerged attack, shooting exercise torpedoes at a zigzagging target ship. Each officer scored a direct hit, demonstrating skills normally possessed by far more experienced submariners. Impressed, the division commander qualified Cutter and the other officers both in submarines and for command on the same day.

Shortly thereafter, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and in the subsequent crucible of war, Cutter learned invaluable lessons about combat operations. By the time he detached from the Pompano in the fall of 1942 to report to the Seahorse—under construction at Mare Island Naval Shipyard—he was a hardened submarine veteran.6

Cutter’s new CO, Commander Donald McGregor, impressed Cutter with his high standards during the Seahorse’s fitting out. But once the submarine reached her patrol area, Cutter realized McGregor was afraid to press home attacks. Convinced that sonar-equipped escorts would find and sink the sub, McGregor refused to attack targets escorted by potentially sonar-capable vessels. Cutter increasingly urged his reluctant CO to attack, relating his experiences in the Pompano to justify his recommendations. McGregor rejected every aggressive suggestion and began calling Cutter crazy in front of the Seahorse’s crew. Things reached the point that McGregor ordered Cutter to remain in his stateroom.7

When the Seahorse’s message detailing the disappointing results of her first war patrol arrived in Pearl Harbor, Pacific Fleet Submarine Force Commander Rear Admiral Charles A. Lockwood and submarine force training officer Captain John H. “Babe” Brown recognized that the submarine needed a change in leadership. Lockwood had taught Cutter seamanship at the Naval Academy, and Brown had been an officer manager for Cutter’s Naval Academy football team. Not only had they known Cutter for a decade, but they also knew the personalities and experiences of the leadership team in the Seahorse. Without waiting for extra details, Lockwood and Brown made the decision to detach McGregor and fleet-up Cutter to command.8

Team Seahorse

The Seahorse’s crew did not welcome the change. They realized they were not successful, but as far as they knew, Cutter was part of the problem. McGregor’s frequent criticisms of him had taken a toll, and the chief of the boat (COB), Chief Quartermaster Joseph McGrievy, informed the new CO: “There’s some of our people don’t want to go to sea with you. They think you are a madman.” Cutter told McGrievy to take only volunteers on board the Seahorse. The next day, McGrievy told the crew, “If you don’t want to go to sea with Slade, take one step forward. And when you take that step, know that you will be going elsewhere.” Only one sailor stepped forward.9

But even with an all-volunteer crew, Cutter wanted a charismatic leader to support him and help rebuild trust with the crew. His chance came when Admiral Lockwood came out to Midway Atoll, where the Seahorse was preparing for her next war patrol, and asked Cutter what he needed. He replied, “I would like to have Ralph Pleatman for one war patrol.”10

It was a brilliant choice. Pleatman had graduated from the Colorado School of Mines in May 1941, among one of the first V7 Reserve Officer Training Corps classes. He also was proudly Jewish, at a time when there were few Jewish naval officers.11 After graduation, he reported to the Pompano, where he befriended Cutter. It was an awkward beginning: The CO, Lew Parks, declared that he intended to run Pleatman off the Pompano in a month because he was both a reservist and a Jew. But Pleatman was a wizard at operating the submarine’s torpedo data computer (TDC), and he was an inspiring junior leader. His superb capabilities eventually won over his prejudiced CO and impressed Cutter.12

On board the Seahorse, Pleatman quickly justified Cutter’s confidence. Cutter recalled: “Pleatman did a magnificent job. He just turned the crew around . . . because he was just as aggressive as hell and he supported everything I wanted him to do.”13

In addition to Pleatman, Cutter turned to other skilled personnel. The COB, Chief McGrievy, had remarkable night vision. Although most COs conned their submarines in combat, Cutter trusted McGrievy so much he chose him to conn the Seahorse:

I would put [McGrievy] on the periscope. I couldn’t see anything, but he could see those black hulks through the periscope. . . . And he was also officer of the deck [OOD] . . . as a chief petty officer, at night during our battle stations. When we made night surface attacks, I was in the conning tower where I had the TDC. He was feeding the data such as bearing and disposition of ships down from the bridge. He was invaluable and absolutely fearless; nothing bothered McGrievy.14

In addition to relying on skilled sailors such as Pleatman and McGrievy, Cutter showed a willingness to listen to the input of the Seahorse’s crew. After an attack, he typically would sit in crew’s mess with his sailors and get their feedback.15

The Seahorse crew proved to be a winning team. In the East China Sea, the submarine sank five ships, repeatedly evading detection and counterattack. Running low on torpedoes, Cutter and his crew started brainstorming how to exit through the heavily-patrolled islands surrounding the sea. Admiral Lockwood wrote: “As Seahorse prepared to leave the Sea some remark was made in the conning tower as to how tough it would be to get through the pass, whereupon the helmsman, a signalman second class named White, evidently thinking out loud, said he believed they could get out on the surface in broad daylight because the Japs would not be expecting it.”16 While Lockwood’s account may not be entirely accurate (there was no one on board the sub named “White” at that time), the Seahorse’s war patrol report confirms that she did partially transit out of the East China Sea in daylight, and the story certainly is in keeping with the teamwork emblematic of the boat.17

After the Seahorse returned from this successful war patrol, her crew demonstrated their newfound team spirit. When the patrol began, Pleatman repeatedly had motivated the crew with his catchphrase: “Fuck ’em, let’s go!” Because it was a more refined era, Cutter told Pleatman to use cleaner language. Pleatman changed his wording to “Fuke ’em, let’s go!” The phrase became the crew’s motto—when the Seahorse pulled into port, she was proudly flying a “Fuke ’em” pennant.18

Babe Brown Protects Cutter from Himself

In three subsequent war patrols, the Seahorse and Cutter continued to be tremendously successful. During his second war patrol in command, the Seahorse encountered a Japanese convoy and over the next 82 hours, she wiped it out. Cutter never even had a chance to change out of the pajamas he started the battle in.19

As success followed success, Cutter’s confidence grew and grew, until he became truly nonchalant about Japanese antisubmarine warfare (ASW). Ultimately, Babe Brown sent Cutter home for a month of leave, telling him a more senior officer was going to take over the Seahorse for one war patrol. When Cutter arrived home, he had orders detaching him from the Seahorse and assigning him to a new construction submarine. While initially he took the news of his relief poorly, eventually he realized Brown had saved his life: “I learned after the war that Admiral Brown felt I was becoming too contemptuous of the enemy ASW and reckless. When he gave me a month’s leave, he had no intention of giving Seahorse back to me. . . . Had I gone on a fifth patrol as skipper, I might not have come back. Babe Brown was an insightful man.”20

Shortly after Brown relieved Cutter from command, Commander Samuel D. Dealey and the USS Harder (SS-257) were lost on a war patrol. Dealey was on his sixth patrol as captain, and his former executive officer (XO), Frank Lynch, believed he had been in command too long: “Sam was showing unmistakable signs of strain. He was becoming quite casual about Japanese antisubmarine measures. Once, on the previous patrol, I found Sam in a sort of state of mild shock, unable to make a decision.”21 Many submariners blamed the Southwest Pacific submarine force commander, Rear Admiral Ralph Christie, for sending Dealey out on one patrol too many.22

The Legacy of Slade Cutter and the Seahorse

About nine months after Cutter was relieved, the Seahorse was surprised and heavily depth charged by Japanese patrol craft. The depth charging was one of the most severe any U.S. submarine survived, and for a brief period, it appeared the Seahorse might be stuck on the ocean bottom. Working as a disciplined team, however, the crew brought the badly damaged submarine back home.23

The continued success of the Seahorse was a tribute to Cutter’s training and the crew’s strong teamwork. The story of this superb crew and its greatest CO offers lessons for today’s Navy.

Team experiences should be emphasized, and individual training must be deep. Cutter directly correlated team sports to his experience in command, stating:

I trained my Seahorse crew the same way I did my battleship Idaho football team years before. On each training period we would start with the individual and the fundamentals, then on to department training, then molding all departments into a team for surface gunfire and another team for battle stations, torpedo. The important thing was to develop in each man self-confidence and confidence in his team.24

However, it was not just Cutter’s sports background that prepared him for leadership success, but also his rigorous apprenticeship under Lew Parks.

Cutter’s background speaks to the experiences and potential the Navy should seek in future officers: team players who can master complex systems. And warfighting training must be comprehensive and thorough to develop mastery. There is a reason that three of the most successful training programs in the Navy—nuclear power training, flight school, and Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL school—are time-intensive and in-depth. Despite fads such as computer-based learning, warfighting mastery continues to require immersive training and a period of apprenticeship.

The Navy should look for talent failed by the meritocratic system. Before the Seahorse returned to Midway after her failed first war patrol, Donald McGregor tried to end Cutter’s career by writing an adverse fitness report and recommending Cutter be detached from submarine duty and assigned to athletic duties at the Naval Academy. Fortunately, Lockwood and Brown intervened before McGregor’s sabotage could sideline Cutter from the war.25

Of note, it was not the only time Babe Brown’s astute talent scouting benefited the submarine force. About a year earlier, he similarly saved the career of Dudley W. “Mush” Morton, who had been relieved for poor performance while in command of the USS Dolphin (SS-169). Brown gave Morton a second chance, resulting in Morton’s famous command of the USS Wahoo (SS-238). Both Cutter and Morton were among the top three U.S. submarine aces of World War II—and Morton trained the third, his Wahoo XO, Richard H. “Dick” O’Kane.26

Cutter and Morton are reminders that the Navy’s meritocratic system can fail and that good—and bad—actors make mistakes that deprive the Navy of much-needed talent. Before World War II, opportunities for second chances such as those afforded Cutter and Morton were commonplace. After all, Ensign Chester W. Nimitz was found guilty at court-martial for running the USS Decatur (DD-5) aground in 1908, and Lieutenant Thomas C. Hart was relieved from command of the USS Lawrence (DD-8) in 1906 for insubordination. Today, both situations likely would be career-ending, but a century ago, the Navy was more forgiving and both officers ended up as admirals in command of fleets in World War II.27 The Navy once again needs to systematize second chances; the United States can ill-afford to squander a present-day Morton, Cutter, Hart, or Nimitz.

Great teams are made up of volunteers whose talents are unleashed. The Seahorse was not the only warship in which leadership demanded an all-volunteer team. Mush Morton started his command of the Wahoo by making a similar offer to transfer anyone who didn’t wish to sail into harm’s way. Eighty years earlier, Lieutenant John Worden similarly shipped only volunteers on board the USS Monitor before she battled the CSS Virginia.28 Arguably, the realization that everyone was sailing into danger by choice helped bond these crews into teams.

Team players such as Ralph Pleatman and Joe McGrievy made significant and unorthodox contributions to making the Seahorse a winning team. While Pleatman and McGrievy clearly were exceptional, they were not unique. During World War II, other great submarines similarly relied on the talents of junior personnel. For example, leaders of both the USS Jack (SS-259) and Harder assigned their most talented junior officers to serve as TDC operators, bypassing more experienced officers with less skill. Morton broke with convention by directing his XO, Dick O’Kane, to man the periscope during submerged approaches.29 Admittedly, Cutter’s reliance on an enlisted sailor to serve as OOD, even one who was the senior-most enlisted sailor on board, was practically unheard of. But the decision best paired McGrievy’s gifts and skills with the Seahorse’s needs. Like Cutter and his Seahorse team, present-day COs and units should seek talents within the ranks and use them.

Mentors need to protect COs from their own overconfidence. The 2001 USS Greeneville (SSN-772), 2012 Montpelier (SSN-765), and 2017 John S. McCain (DDG-56) collisions were driven in part by overconfident COs who circumvented their teams.30 By his own admission, Slade Cutter nearly joined their ranks. The dispassionate intervention of a senior mentor, Babe Brown, proved to be what made the difference.

The examples of Cutter, Sam Dealey, and the recent mishaps should remind present-day senior leaders to look for signs that successful COs are growing overconfident and undermining their teams. The Navy should develop processes that permit senior leaders to detach COs and allow them to recharge and return them to command, possibly at a different unit, without harming their careers.

Slade Cutter and the Seahorse left behind a legacy of success and lessons worth revisiting. Today’s senior naval leaders would do well to display the mentorship shown by Lew Parks, Charles Lockwood, and Babe Brown—whether in grooming and promoting future leaders or protecting those leaders from themselves. Commanding officers should learn from Slade Cutter’s team-oriented leadership style. And sailors should find inspiration from the example of team players such as Pleatman and McGrievy. A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority lays out the lines of effort that will provide materiél and personnel for the future U.S. Navy, but the outstanding leaders and teams necessary for U.S. maritime superiority will man the rails only if the service heeds the lessons of Captain Slade Cutter and the USS Seahorse.

1. ADM John M. Richardson, USN, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority, Version 2.0, December 2018, 16.

2. Dave Bouslog, Maru Killer: War Patrols of the USS Seahorse (Placentia, CA: R. A. Cline Publishing, 1996), 322.

3. “The Reminiscences of Captain Slade D. Cutter, U.S. Navy (Retired),” oral history conducted by Paul Stillwell, 2 vols. (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1985), 2, 27.

4. Cutter, oral history, 4–6, 61–64, 78–81.

5. Cutter, oral history, 48, 50, 81–82, 112–13, 118–21.

6. Cutter, oral history, 123–28, 160–63, 171–88, 192–209, 229–33, 239–49, 256–58, 298–303.

7. Cutter, oral history, 69–70, 149–55, 258–64, 266–67.

8. Cutter, oral history, 55, 60–61, 69–70, 152, 264–65. See also: Bouslog, Maru Killer, 70.

9. CDR Joseph McGrievy, USN (Ret.), in Sub: An Oral History of U.S. Navy Submarines, ed. by Mark Roberts (New York: Berkley Caliber, 2007), 22–23.

10. Cutter, oral history 68–71.

11. “Ralph F. Pleatman,” The Cincinnati Enquirer, 3 February 1988, F-4; “From the Pages,” The American Israelite, 14 November 2018.

12. Cutter, oral history, 68.

13. Cutter, oral history, 74.

14. Cutter, oral history, 236–37.

15. Carl LaVO, Slade Cutter: Submarine Warrior (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2003), 130.

16. VADM Charles A. Lockwood, USN (Ret.), Sink ’Em All: Submarine Warfare in the Pacific (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co. 1951), 143.

17. “USS Seahorse (SS-304) Second War Patrol Report,” 14.

18. Cutter, oral history, 74.

19. Cutter, oral history, 53–54.

20. Bouslog, Maru Killer, 219–20.

21. Clay Blair Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War against Japan (Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Company, 1975), 717.

22. Blair, Silent Victory, 720.

23. “USS Seahorse (SS-304) Seventh War Patrol Report,” 11–13, 23–24, 26, 30; see also the endorsements by Commander, Submarine Division 104; Commander, Submarine Squadron 4; and Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet. See also: Bouslog, Maru Killer, 283–303.

24. Blair, Silent Victory, 518.

25. Cutter, oral history, 68–69, 153–54, 264.

26. Blair, Silent Victory, 251, 381–86, 878, 984.

27. E. B. Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976), 61–62; James Leutze, A Different Kind of Victory: A Biography of Admiral Thomas C. Hart (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1981), 31–32.

28. Forest J. Sterling, Wake of the Wahoo: The Heroic Story of America’s Most Daring WWII Submarine, USS Wahoo (Riverside, CA: R. A. Cline Publishing, 1999), 72. John V. Quarstein, “The Monitor Boys,” Naval History 26, no. 2 (April 2012): 22.

29. VADM James F. Calvert, USN (Ret.), Silent Running: My Years on a World War II Attack Submarine (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1995), 14–15. RADM Richard H. O’Kane, USN (Ret.). Wahoo! The Patrols of America’s Most Famous World War II Submarine (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1987), 114.

30. VADM John B. Nathman, USN; RADM Paul F. Sullivan, USN, RADM David M. Stone, USN; and RADM Isamu Ozawa, JMSDF to Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet; 13 April 2001, “Court of Inquiry into the Circumstances Surrounding the Collision Between USS Greeneville (SSN-772) and Japanese M/V Ehime Maru that Occurred off the Coast of Oahu, Hawaii on 9 February 2001,” Opinions paras. 9, 10, 14, 22–26, 31–32, 39–42, 52. Commander, Submarine Force Atlantic to Commander, U.S. Fleet Forces Command, 21 December 2012, Ser N00/S034, “Command Investigation into the Collision Involving USS San Jacinto (CG-56) and USS Montpelier (SSN-765),” para. 1.e. Admiral P. S. Davidson to Vice Chief of Naval Operations, 26 October 2017, Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents, 11–13.