This article is adapted from Craig Symonds’ book Operation Neptune: The D-Day Landings and the Allied Invasion of Europe (Oxford University Press, 2014).

The first Allied soldier stepped ashore on Omaha Beach at 0640 on 6 June 1944, and immediately found himself in a virtual hell of machine-gun and artillery fire. “Drenching fire” from a naval bombardment, which was supposed to have softened up the beach and demoralized defenders, had been too brief. Bombs from hundreds of Allied aircraft had fallen inland well beyond the beach, and rockets from the rocket-firing LCTs (landing craft, tank) offshore had mostly landed too short.

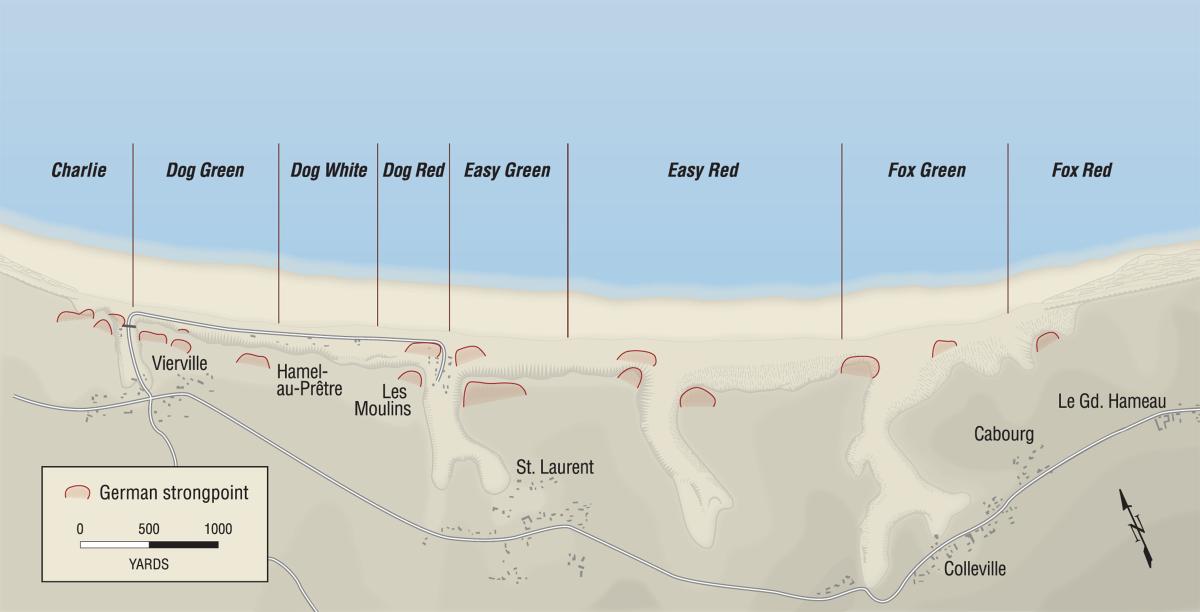

As a result, the German defenders were able to emerge from their concrete bunkers and man the 85 machine-gun positions behind the beach and on both flanks and initiate a merciless fire. That made it impossible for naval combat demolition units (NCDUs) to disable or neutralize all of the many beach obstructions. As a result, despite months of careful planning and preparation, the men in the first several waves were targeted by fierce and relentless machine-gun fire.

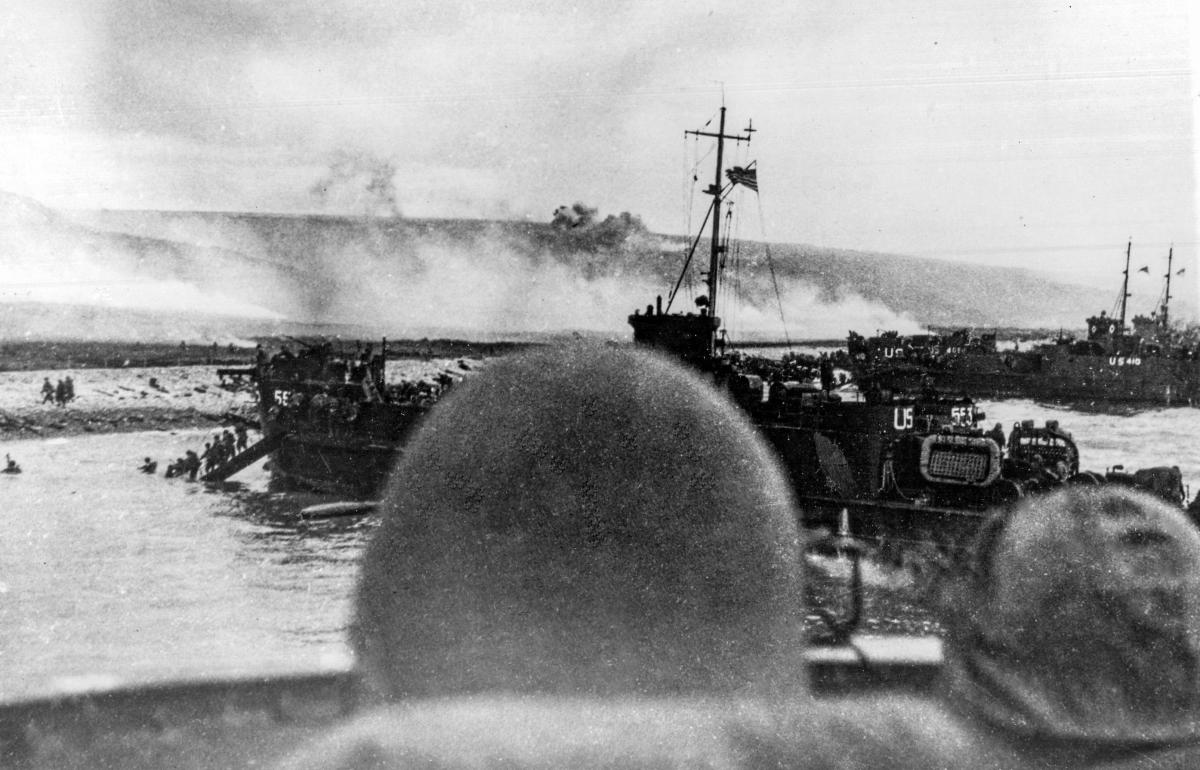

By 0800, it had become a mess. Those soldiers who had landed, and those sailors forced to join them when their craft were wrecked, sheltered precariously and imperfectly behind a low ridge a few hundred yards inland from the surf line, their faces pressed into the smooth stones of the beach’s shingle in a vain effort to avoid the machine-gun bullets passing only inches over their heads. Landing craft maneuvered awkwardly offshore vainly seeking a place to land along a beach crowded with still-extant obstacles and scores of burning or wrecked Allied landing craft. And all the while, the relentless tide continued to mount the beach, faster than some of the wounded could crawl, reducing slowly but inexorably the narrow strip of land where men could still live.

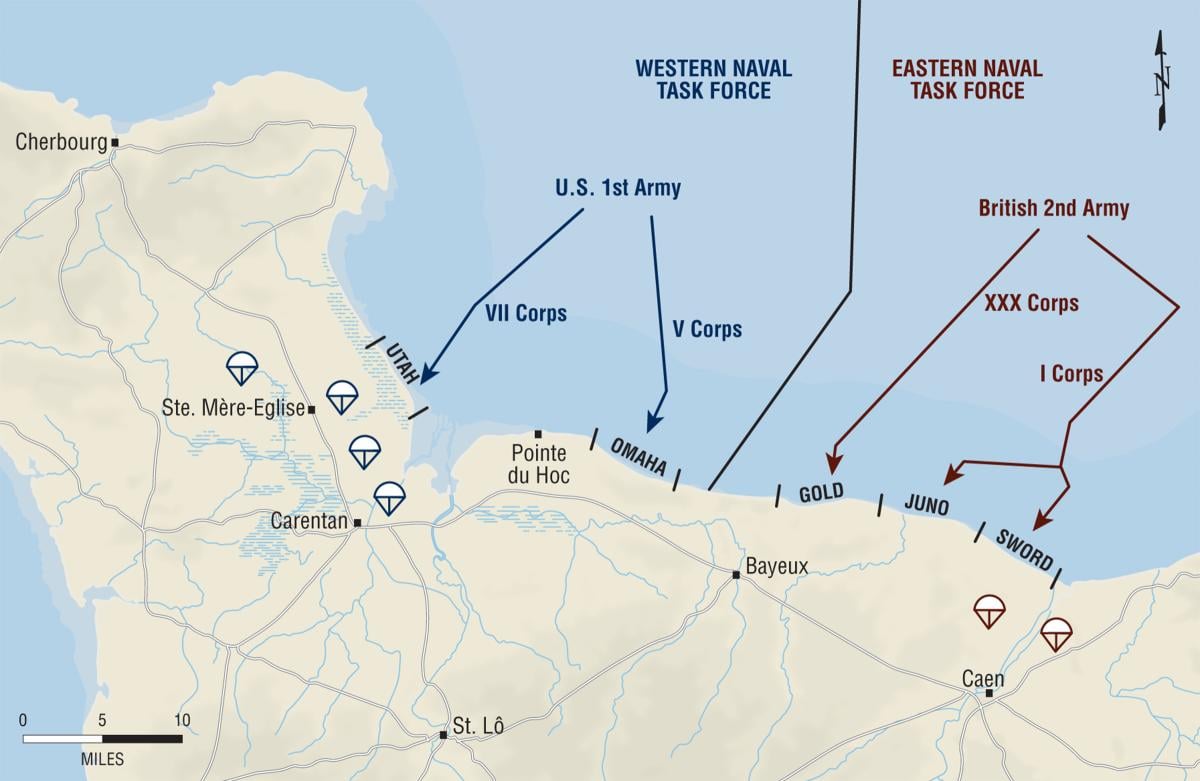

At 0830 the beachmaster on Omaha notified Rear Admiral John “Jimmy” Hall, who commanded the ships of “Force O” offshore, that “they were stopping the advance of follow up waves.” Only two hours after it had started, the invasion of Omaha Beach had stalled. Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, commander of the U.S. First Army, confessed later that he was contemplating “evacuating the beachhead and directing the follow up troops to Utah Beach or the British beaches.” Horrified by the prospect of failure, he asked Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk, who commanded the Western (American) Naval Task Force, if there wasn’t something more the Navy could do to break the bloody stalemate on Omaha Beach. As it happened, there was.

Destroyers to the Rescue

Most of the American destroyers that had participated in the early-morning bombardment of the beaches had retired offshore prior to H-hour, partly to make room for the landing craft and partly to take up screening positions to seaward. Nevertheless, the destroyer skippers could see for themselves that the situation on Omaha was deteriorating, and even without orders, some of them had returned to the beachfront to open fire on the high ground behind the beach. Now, just past 0830, Hall recalled the rest, ordering them to “maintain as heavy a volume of fire on beach target[s] as possible.” In support of that, Rear Admiral Carleton Bryant, commanding the big ships of the bombardment group off Omaha Beach, radioed a general message from the USS Texas (BB-35): “Get on them, men! Get on them! They are raising hell with the men on the beach, and we can’t have any more of that! We must stop it!”

The destroyer captains responded with enthusiasm—indeed, almost too much enthusiasm. Most of the responding ships were American Gleaves-class destroyers that drew more than 13 feet of water, and the gradual slope of Omaha Beach made close-in fire support extremely hazardous. It was self-evident that if a destroyer grounded in the shallows, the German gunners could blast her to pieces at their leisure. Nevertheless, the destroyers now came speeding shoreward at 20 knots or more into water that was both unmarked and outside the mine-swept channels.

One sailor on board an LCT that was approaching the shore was shocked to see “a destroyer ahead of us with heavy smoke pouring from its stack.” The ship appeared to be out of control and headed directly for the beach. “My God,” he thought, “they’re going to run aground and be disabled right in front of the German artillery.” At the last minute, the destroyer made a sudden hard left, turned her starboard side parallel to the beach, and began “blazing away with every gun it had, point blank at the defensive positions.” The sailor was thrilled to see “Puffs of smoke and mounds of dirt” flying “everywhere on the hillside as the destroyer passed swiftly by.”

More than a dozen Allied destroyers responded to the call that morning, nine of them from Destroyer Squadron (DESRON) 18, under the command of U.S. Navy Captain Harry “Savvy” Sanders. Two of Sanders’ destroyers, the Satterlee (DD-626) and Thompson (DD-627) along with HMS Talybont, supported the U.S. Army Rangers assigned to assault the nearly vertical cliff at Pointe du Hoc west of Omaha Beach. Two more, the Carmick (DD-493)and McCook (DD-496), joined later by the Harding (DD-625), took up positions near the center of Omaha Beach off St. Laurent-sur-Mer, and five others, led by the squadron flagship Frankford (DD-497) with Sanders on board, steamed for the eastern end of the beach opposite Colleville-sur-Mer.

Most of the destroyers took up positions only 800 to 1,000 yards off the beach, so close that, as a newspaper correspondent reported, ”Germans were hitting them with rifle bullets.” Though the gradients varied across the beachfront, at that distance the water depth was only about 12 to 18 feet. Sanders later speculated that there were moments when the Frankford had only a few inches of water under her keel, and Kirk later asserted that “they had their bows against the bottom.” Even if that were not literally true, it suggested the willingness of the destroyer captains to put their ships at risk in an obvious emergency. These dozen or so destroyers constituted only a tiny fraction of the more than 5,000 ships that participated in the invasion of Normandy, but over the ensuing 90 minutes, they turned the tide of battle on Omaha Beach.

Aiding Army Rangers

Several destroyers also played a key role in what was perhaps the most daunting assignment of the entire invasion: the assault by 225 U.S. Army Rangers under Lieutenant Colonel James A. Rudder on Pointe du Hoc. Atop this nearly vertical cliff, the Germans were believed to have placed several heavy guns that could reach both of the American beaches—Omaha and Utah. To eliminate this threat, the Rangers would have to land on a narrow rocky beach at the base of the cliff, and then scale the cliff with ropes and ladders. Only 108 of the men who began the climb made it to the top. With so few of them, and arriving piecemeal as they did, their mission was touch and go.

A crucial factor in their eventual success was gunfire support from the destroyers. Hard pressed by German light artillery, the Rangers used a blinker light to send target coordinates to the destroyers offshore. The Satterlee responded first, joined by the Thompson at 0830 and by the Ellyson (DD-454) an hour later. Unable to see the target, the destroyers had to rely on indirect fire, stopping after each salvo to receive a report from the Rangers about the fall of shot. At 0952, the Rangers called for the destroyers to cease fire, and at 1130, lookouts in the destroyers saw an American flag flying over the position.

Having scaled the cliffs, driven off the defenders, and seized the high ground, however, the Rangers soon discovered that the reported big guns on Pointe du Hoc had been removed, replaced by wooden dummies. They moved inland and set up a defensive perimeter, which they held for the rest of the day and into the night.

Trying to Find Targets

The other destroyers of Sanders’ squadron, operating off Omaha Beach itself, had great initial difficulty identifying appropriate targets. The poor visibility along the beachfront and the excellent German camouflage made it all but impossible to figure out where the German guns were. Some of those guns retracted into underground bombproofs; others were so well hidden that, as one sailor put it, “you couldn’t see it if you was ten feet from them.” In theory, the ships were supposed to coordinate with shore-based fire-control parties that would identify the targets and report the fall of the shot, as the Rangers did at Pointe du Hoc. But there was such chaos on the beach that morning and such a dearth of working radios that not until the afternoon did the destroyers establish regular radio communication with spotters ashore. In the meantime, the destroyer skippers were compelled to seek “targets of opportunity.” There was one immediate benefit of their arrival, however. Many of the German gunners, fearful of disclosing their location, briefly held their fire. Others shifted their fire to target the destroyers, and in either case, that created a blessed, if temporary, respite for the soldiers on the beach.

Near the center of Omaha Beach, just off the beachfront village of Les Moulins, Commander Robert Beer, the tall, lanky captain of the Carmick, scanned the bluffs looking for telltale “puffs of smoke or flashes from enemy gun emplacements.” Because the Germans were using smokeless powder, he saw none, and Beer became impatient, finding the process “slow and unreliable.” As he studied the beach through his binoculars, however, he noted a few Allied tanks trying vainly to fight their way up the draw, or gully, in the cliffs near Vierville-sur-Mer. It was evident to him that they were being held up by heavy gunfire from above, though he could not identify the source of that fire.

Several of the Allied tanks were shooting at a particular spot on the bluffs, and carefully noting the location, Beer directed his ship’s guns to target those same positions. The Carmick fired a series of rapid-fire salvoes from her 5-inch guns into the suspicious area. After a few minutes, Beer saw that the tank gunners had shifted their fire to another site, and Beer directed his gunnery officer to follow suit. “It became evident,” Beer reported afterward, “that the Army was using tank fire in [the] hope that fire support vessels would see the target and take it under fire.” In a kind of deadly pas de deux, the tank men used their shells to point out enemy gun positions, and the destroyermen aimed accordingly.

Near the Carmick, Lieutenant Commander Ralph Ramey, in the McCook, opened fire on two strongly fortified German guns set into the cliff face. Many of Ramey’s friends thought he was the spitting image of the comedian Will Rogers, and Ramey often sprinkled his conversation with country aphorisms, but he was all business now. Ramey and the McCook maintained an unremitting fire at the German battery for more than 15 minutes, and eventually that concentrated bombardment undermined the rock strata on which the enemy guns rested. The cliff crumbled away; one of the guns flew up into the air, and the other plunged down the cliff face.

A mile or two farther east, Commander James G. Marshall, captain of the Doyle (DD-494), maneuvered his ship among the landing craft that were swarming off the Fox Green sector of Omaha Beach. From only 800 yards off the surf line, Marshall could see the men ashore “dug in behind a hummock of sand along the beach, and the boats of the second wave [actually the third] milling around offshore.” Absent contact with fire-control parties ashore, he posted lookouts to scan the high ground behind the beach for evidence of enemy gun positions, though visibility was “very difficult because of smoke and dust in the target area.” One lookout reported a machine-gun emplacement on a steep hill at the west end of Fox Red Beach between Colleville-sur-Mer and Le Grand Hameau, and the Doyle fired two salvoes onto the site. The Doyle then shifted fire to a casemate at the top of the hill, fired two more salvoes, and in both cases, Marshall was able to report: “target destroyed.”

More often, however, the results were less conclusive. Lacking other clear sightings, Marshall simply picked out what seemed to him to be logical places for gun positions to be and opened fire on them even if he could not see anything there. Having completed her assignment off Pointe du Hoc, the Thompson joined the Doyle off Fox Green Beach, and there her commander, Lieutenant Commander Albert Gebelin, whose darkly handsome features reminded some of a cigar-store Indian, directed his ship’s fire into a clump of trees that he thought might be cover for a field battery. Whether it was or not, the trees got a thorough pounding.

Other ships got into the act. A sailor on board an LCT happened to be looking at the vegetation along the line of bluffs when he noticed a tiny movement among the bushes, and a second later a shell exploded on the beach. He kept his eye focused on those bushes, and soon another small movement of the brush was followed by another explosion on the beach. He called the skipper over and pointed it out. The officer watched as the pattern was repeated, and he noted the coordinates on his chart. He then got on the short-range TBS radio and called the nearest of the destroyers. Almost at once a destroyer “came barreling in there, popped over sideways, port side to the beach, and turned loose about eight rounds of 5-inch projectiles” into the German gun position.

Pounding the Enemy

Compared to the aerial bombs dropped from high altitude and the big shells fired by the battleships and cruisers from 10 or 15 miles offshore earlier that day, the smaller-caliber destroyer fire was more accurate and therefore far more effective. The morning’s 8-, 12-, and 14-inch shells had made the ground shake, but they had left the German gun positions largely intact. Now those positions were pounded with hundreds of 5-inch shells and knocked out, one by one. One witness recalled seeing three 5-inch shells hit within 20 inches of a narrow gun slit in a pillbox, and in at least one case, a German artillery piece was hit directly on the muzzle and split wide open.

A beachmaster on Omaha, watching the “tin cans” fire into the cliff, later claimed, “You could see the trenches, guns, and men blowing up where they were hit.” There was no doubt in his mind that “the few Navy destroyers that we had there probably saved the invasion.” With more enthusiasm than precision, he insisted that the handful of American ships “destroyed practically the entire German defense line at Omaha Beach.” If they didn’t quite do that, they did change the trajectory of the battle. Inside an artillery bunker behind Omaha Beach, a German regimental commander phoned headquarters to report: “Naval guns are smashing up our strongpoints. We are running short of ammunition. We urgently need supplies.” There was no answer because the line had gone dead.

For more than an hour, from shortly before 0900 until well past 1000, the destroyer gunfire was virtually nonstop. And it needed to be. As a landing craft filled with 200 soldiers headed for the beach, her commanding officer noted that “If a destroyer ceased shelling a shore battery for even a very brief time, the battery resumed fire on the craft along the beach.”

Of course the constant firing soon depleted the ammunition stores on board the destroyers. To ensure that they retained sufficient capability for emergencies, the Operation Neptune invasion order had specified that the destroyers were to expend no more than 50 to 60 percent of their ammunition before going back to England to replenish. In this crisis, however, the destroyer skippers disregarded that injunction. Gleaves-class destroyers carried between 1,500 and 2,000 rounds of general-purpose 5-inch ammunition. Most of the ships in Sanders’ squadron had fired off between a quarter and a third of that during the morning bombardment, and now they expended most of what was left.

Between 0850 and 1015 that morning, the Emmons (DD-457) fired 767 rounds, the McCook fired 975, and the Carmick 1,127. Kirk became sufficiently nervous about this that he issued an order that “destroyers must husband [their] ammunition,” reminding them, “our resources are limited.” When the gunners in the Herndon (DD-638) ran out of high-explosive ammunition, they began firing star shells, primarily used for illumination. On board the Butler (DD-636), Petty Officer Felix Podolak remembered that the firing was so hot “We had to hook up one-and-a-half-inch fire hoses to hydrants to spray water on our gun mount,” and even then, “the barrels were running red hot.”

The German gunners fired back, mostly with their mobile 88-mm guns, but the swift destroyers were difficult targets, even in the shallow and crowded waters off Omaha Beach. The destroyer skippers used their engines “in spurts,” ordering them alternately “ahead and astern, to throw off the enemy gunners.” There were some close calls. A German battery behind Fox Red Beach straddled the Emmons, and the Baldwin (DD-624) was hit twice in rapid succession, the first shell striking her whaleboat on the starboard side, and the second blowing an 8-by-12-inch hole in her main deck. But the Emmons escaped injury, and the Baldwin responded with accurate counterbattery fire, silencing her tormentor after several salvoes. No other destroyer was hit during this crucial and decisive 90 minute period along Omaha Beach.

Successes and Errors

Shortly before noon, the accuracy of the destroyer gunfire improved when the ships finally established contact with some of the fire-control parties ashore. At 1124 Army spotters directed the fire of the Frankford into a concentration of German troops behind the beach and beyond the sightline of the destroyers. After two salvoes, the spotters called a cease-fire because the soldiers had scattered.

Given the dearth of working radios ashore, and the complications of interservice communication, it is not surprising that there were errors. Late that afternoon, several of the American destroyers received reports that the Germans were using the church steeples in both Colleville-sur-Mer and Vierville-sur-Mer as observation posts. The Emmons took on the task of taking down the steeple in Colleville, and after a few salvoes, she did, smashing it, as one sailor recalled, “just like you’d hit it with a big ax.” A few miles to the west, off Vierville, the Harding took the church there under fire. From offshore the results looked spectacular. The Harding’s first salvo clipped off the cross at the peak, the second hit the steeple about ten feet from the top, and the third hit ten feet below that. From seaward it looked like the Harding was slicing off the steeple ten feet at a time, and Admiral Bryant, watching from the bridge of the Texas, thought it was “a beautiful sight.” The reality on the ground was much different. Not only did the shelling cause a lot of collateral damage, but far worse, U.S. troops had already captured the town, and the Harding’s shells killed and wounded a number of Americans. Army Captain Joseph Dawson of the 16th Infantry thought it was “totally disgraceful.”

Despite such errors, the cumulative effect of the close-in naval gunfire support was decisive. For the first time since they had landed, the men lying face-down behind the low rise of sand and shingle at the high-tide mark were able to lift their heads and look around them for a way off the beach. As early as 1036, lookouts on board the Frankford noted that some Allied troops were beginning to advance, moving forward from that low hillock of sand toward the base of the cliffs. And an hour later, at 1137, some of the German defenders began coming out of their positions with their hands up. While much of this was the result of incredible bravery and determination by the soldiers themselves, the destroyers played a critical role. In his postwar memoir, Bradley acknowledged that “the Navy saved our hides.”

Sources:

Action Reports of USS Carmick, Doyle, Ellyson, Emmons, Frankford, Laffey, McCook, and Thompson, all in Special Collections, Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD.

Action Report of LCI(L)-408, LCI Association Papers, National Museum of the Pacific War, Fredericksburg, TX.

Thomas B. Allen, “The Gallant Destroyers on D-Day,” Naval History, vol. 18, no. 3 (June 2004), 18–23.

Omar Bradley with Clay Blair, A Soldier’s Life: The Autobiography of General of the Army Omar N. Bradley (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1983).

William B. Kirkland, Destroyers at Normandy: Naval Gunfire Support at Omaha Beach (Washington, DC: Naval History Division, 1994).

Samuel Eliot Morison, The Invasion of France and Germany, 1944–1945, vol. 11 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II (Boston: Little Brown, 1957).

Edward F. Prados, ed., Neptunus Rex: Naval Stories of the Normandy Invasion, June 6, 1944 (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1998).

Theodore Roscoe, United States Destroyer Operations in World War II (Annapolis, MD: U.S. Naval Institute, 1953).

Paul Stillwell, ed., Assault on Normandy, First-Person Accounts from the Sea Services (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1994).

Oral histories of George Bauernschmidt, Joel G. Smith, Robert Miller, William Steel, Joe Esclavon, Felix Podolak, Curtis Hansen, Karl Everett, Robert Evans, and Clifford Sinnett, all in the Eisenhower Center, National World War II Museum, New Orleans, LA.