During the fall of 1861, the Confederacy became acutely aware of the necessity for an active foreign policy that would be, in some way or another, effective in promoting Confederate interests abroad. It was especially desired to gain recognition from both France and England. To this end, Jefferson Davis decided to send James Mason of Virginia and John Slidell, a Northerner by birth but now of Louisiana, to England and France respectively. They were to be accompanied by their personal secretaries, George Eutis and James McFarland.

Mason and Slidell succeeded in running the blockade at Charleston, South Carolina, on the night of 12 October 1861 on the Confederate steamer Theodora, and arrived at New Providence, Nassau, on the 14th, thence proceeding by the same vessel to Cardenas, Cuba and from that point journeyed overland to Havana arriving 22October.1 Their plan was to travel to St. Thomas by the British mail packet Trent. From there, they planned to catch a ship bound for Southampton.

During their stay in Havana, they were elegantly wined and dined. While Mason and Slidell were being entertained in such an extravagant manner, Captain Wilkes, the commanding officer of the USS San Jacinto, learned of their intentions to travel to St. Thomas by the Trent.

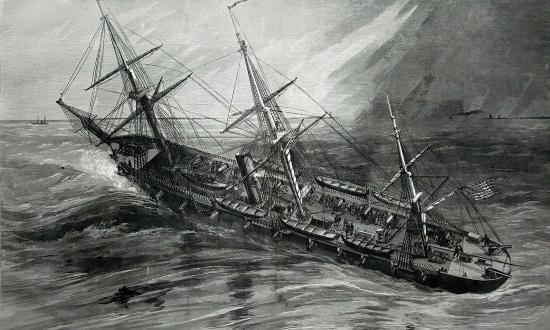

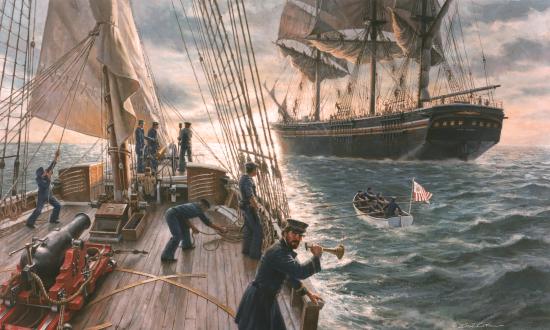

One day out of port, on 8 November about noon, the San Jacinto fired a warning shot across the bow of the British ship. The Trent, apparently, showed no decrease in speed and thus prompted another shot which exploded less than a cablelength forward of the Trent’s bow. The following is an account of what happened as given by Commander Williams R.N., an Admiralty agent on board at the time:

"The Trent the stopped, and an officer with a large armed guard of marines boarded her. [The officer was Lieutenant Fairfax, the executive officer of the San Jacinto.] The officer demanded a list of passengers; and compliance with this order being refused, the officer said he had orders to arrest Messrs. Mason, Slidell, McFarland, and Eustis and that he had certain information of their being on the Trent."2

The Confederate party, therefore, presented themselves, but refused to leave the ship unless physical force be applied to make them do so. Lieutenant Fairfax accommodated them by having his men seize them by their shoulders and collars. Accepting this as an application of physical force, they allowed themselves to be transferred to the San Jacinto. The envoys, especially Slidell, were exultant in the conviction that the action of Wilkes would inevitably result in the early realization of the object of their journey—recognition of the South, at least by Great Britain.3

Their arrival at Fort Monroe created a national stir. The popular feeling was to let these prominent Rebels be treated to the same barbarous solitary confinement to which certain Yankee Congressmen captured at Bull Run had been subjected to in Richmond, Virginia.4 The popular hunger was sated when the group was interned at Fort Warren outside of Boston.

The Trent affair caused very serious repercussions in London. So serious was the nature of these repercussions that the United States and Great Britain were almost forced into a war which neither side wanted. The British were concerned with the international law aspect as well as the “affront to the flag.” They were concerned, principally, with the following.

- That the seizure of the Rebel emissaries without taking the ship into port was wrong inasmuch as a Navy officer is not entitled to substitute himself for a judicial tribunal.

- That had the ship had been carried into port it would not have been liable on account of the Rebel emissaries, inasmuch as neutral ships are free to carry all persons not apparently in the military or naval service of their enemy.

- Are dispatches contraband of war so as to render the ship liable to seizure?

- Are neutral ships carrying dispatches liable to be stopped between two neutral ports?5

The British were gravely concerned with the implications of the seizure of Mason and Slidell. Prior to the interference with the Trent, Lord Palmerston anticipating the possibility of such an event, delved into the question as the British legal experts interpreted the international law that would be applicable in such a case.

His results were made known to Delane in a letter dated 11 November 1861. The context of that letter was:

"According to the principles of international law laid down in-our courts by Lord Stowell [Sir William Scott] and practiced and enforced by us, a belligerent has a right to stop and search any neutral not being a. ship of war, and being found on the high seas and being suspected of carrying an enemy’s dispatches, and that consequently this American cruiser might, by our own principles stop the West Indian packet and search her."6

Although it was not explicitly included in his letter, Palmerston later added that the Law Officers did not decide that Mason and Slidell might be taken out of the packet, but only that we (the British) could not prevent the packet's being interfered with.7 The American cruiser to which Palmerston referred was the USS James Adger which, according to C.F. Adams, the U.S. ambassador to the court of Queen Victoria, had been sent to intercept the CSS Nashville if found in these waters. However, at the time of this message from Adams, Palmerston believed that it was on the C.S.S. Nashville that the Confederate envoys were headed to England.

On receipt of the report of Commander Williams R.N., Earl Russel sent a letter to letter to Lord Lyons dated 30 November 1861: “It thus appears that certain individuals have been forcibly taken from on board a British vessel, the ship of a neutral power, while such vessel was pursuing a lawful and innocent voyage—an act of violence which was an affront to the British flag and a violation of international law.”8

The affair created much unrest in England. There was a strong desire to avoid war, but such expectation of it that orders were issued to hold the fleets in readiness, several thousand troops were sent to Canada, and war supplies were cut off by a proclamation that prohibited further export of arms and ammunition.9 The British were justified in feeling that war was imminent. The British Foreign Office took the stance that if the ships of one country interferes with the ships of another on the high seas, the interference must be justified, or compensation be afforded.10 To the British, there was no justification, which left compensation as the only avenue of peace.

The receipt of the news of the “Trent Affair” had aroused the righteous indignation of the proud British people. Seward, however, cast grave doubts upon our willingness to make compensation. In a letter dated 26 December 1861, Department of State, to Lord Lyons, he said, “This government cannot censure him [Wilkes] for his oversight.”11 The British had not demanded that Wilkes be in any way reprimanded, but by our denial of responsibility, that is, by claiming that Wilkes acted without orders from higher up, and refusing to censure him in some manner indicated that we more or less condoned his actions.

With respect to international law, Seward maintained that persons as well as goods might be contraband, and that even neutral destination does not change their contraband nature nor modify the right to capture them.12 As proof, he offered an out-of-context quote of Lord Stowell, the English authority on international law: “The belligerent may stop the ambassadors of his enemy on their passage.”13 Seward’s argument did not deceive the shrewd men in the Foreign Office in London. They responded with the argument that you may stop the ambassador of your enemy on his passage, but when he arrives and has been taken on the functions of his office, and has been admitted in his representative character, he becomes a sort of middleman, entitled to the peculiar privileges as set apart for the protection of the relations of amity and peace. It was obvious to the British that Sir William Scott, Lord Stowell, was supposing him to be a conveyed toward his destination in the ordinary manner, which is in the vessel of the state to which he belonged.14 The British also pointed out that by a proposition of Benjamin Franklin that enemies, unless soldier in the active service of their country, shall not be taken out of a neutral ship; and second, that such persons are not contraband of war so as to effect of the voyage of a neutral with illegality.15The British apparently had an airtight case against the United States.

The French seemed to think so too. In a letter dated 3 December 1861, to Mosieur Mericer, the French ambassador in Washington, Mosieur Thouvenal says: "Messrs. Mason and Slidell were, therefore, by virtue of this principle, which we have never found any difficulty in causing to be inserted in out treaties of friendship and commerce, perfectly at liberty under the flag of England."16

Lord Lyons communicated the demands of his government to Seward. The English demanded that the Confederate emissaries be released and placed under the protection of the flag of England. Seward then informed Lord Lyons that the four men in question were held in military custody at Fort Warren, in the state of Massachusetts. In his correspondence with Lord Lyons, Seward said that the rebels would be cheerfully liberated if “your lordship will please indicate a time and place for receiving them.”17 This message eased the international tension, but the American populace was in an uproar. However, it was not Seward or Wilkes, but the Navy Department that bore the brunt of the popular disappointment over the release of Mason and Slidel1.18

It would seem that the English had definitely forced the United States to back down in their stand on the Trent affair. However, although the moral victory belonged to the English; the tactical victory belonged to the Americans. As Charles Sumner said, “The seizure of the rebel emissaries on board a neutral ship cannot be justified according to our best American precedents and practices.”19 Even though such famous lawyers as Caleb Cushing and Edward Everett justified Wilkes as having the law with him, Seward realized that here was our opportunity to secure an admission of the rights of neutrals, which we has ostensibly set out and failed to do in the War of 1812.20 These rights were expressly summed by Charles Clark in a speech before the London Juridical Society:

"It is conceived that the carrying of dispatches can only invest a neutral ship with a hostile character in the case of its being employed [specially employed] for that purpose by the belligerent, and that it cannot affect with criminality either a regular postal packet, or a merchant ship which takes a dispatch in its ordinary course of conveying letters, and with the contents of which the master must necessarily be ignorant . . . that where a neutral vessel is pursuing its ordinary employment between a neutral and a belligerent country, the fact that the vessel has received on board in the ordinary way, as casual individual passengers or papers, the officers or the dispatches of one belligerent will not authorize the other belligerent to stop and search it, nor take the persons or papers from on board it."21, 22

Charles Sumner said that “the act became questionable only when brought to the touchstone of the liberal principles which from the earliest times, the American government has openly avowed and sought to advance, and which other European nations have accepted with regard to the sea.”23 Such was the case. We were more interested in being consistent with our previous national policy and obtaining a recognition of this policy from England, than we were in the prevention of any minor success Mason and Slidell might have had in promoting the cause of the Confederacy. Charles Sumner, as well as Seward, recognized this. In a speech before the Senate on 9 January 1862, Summer said, “Do not forget, sir, that the question involved in this controversy is strictly a question of law—on this identical point of law, Great Britain persistently held an opposite ground from that which she now takes.”24 Indeed, it was a point of law now. Any possible aid that Mason and Slidell could have obtained from the English would without a doubt be nonexistent now. It was very doubtful that England would aid to any degree the men which had almost involved her in another unwanted war.

Mason and Slidell were released and reunited with their friends in London just 80 days after their removal from the Trent. This, obviously, is not the important point of the whole affair. The notable feature of the incident was England's complete reversal in her position with regard to maritime neutral rights. We were fortunate that our leaders at the time were able to exploit what, on the surface, seemed to be a diplomatic setback. By reversing the role of neutral and belligerent with England, we had backed them into a corner in which there was but one exit. The exit involved the implicit denial of their customary claim to the right of impressment, and the general support of the basic concepts of the American Treaty Plan of 1776, which secured America’s precedent making concept for the regulation of neutral maritime rights. To Seward belongs the credit for the unpopular, but just and wise decision to release the rebels. The adroit appeal of the politician by which he won support for it cannot rob the statesman of his laurels.25

1. E. D. Adams, Great Britain and the American Civil War (New York, 1925), 204.

2. Pamphlet 2 of the Theta Collection of the library of the United States Naval Academy, “Letters Relative to the Removal of Messrs. Mason, Slidell, Eustis, and McFarland.”

3. Adams, Great Britain and the American Civil War, 205.

4. Richard S. West Jr., Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Navy Department (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1943), 130–131.

5. Charles Sumner, Speech on Maritime Neutral Rights (Washington, D.C.: 1862), 5.

6. Adams, Great Britain and the American Civil War, 208.

7. Adams, 211.

8. Pamphlet 2 of the Theta Collection of the library of the United States Naval Academy.

9. Samuel Flagg Bemis, American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy, 68.

10. Charles Clark, The Trent and the San Jacinto (London, 1862), 12.

11. Pamphlet 2 of the Theta Collection of the library of the United States Naval Academy.

12. Bemis, American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy, 68.

13. Clark, The Trent and the San Jacinto, 29.

14. Clark, 28.

15. Clark, 29.

16. Pamphlet 2 of the Theta Collection of the library of the United States Naval Academy.

17. Pamphlet 2 of the Theta Collection of the library of the United States Naval Academy.

18. West, Gideon Welles, 137.

19. Clark, The Trent and the San Jacinto, 29.

20. Carl Sandburg, Abraham Lincoln: The War Years, vol. 1 (New York: Harcourt, Brace & Company, 1939), 362.

21. Clark, The Trent and the San Jacinto, 33.

22. Clark, 45–46.

23. Sumner, Speech on Maritime Neutral Rights, 6.

24. Sumner, 9.

25. Bemis, American Secretaries of State and Their Diplomacy, 68.