Many artists are recognized for their contemporary work on Civil War topics. Those illustrating naval actions or scenes, however, are few in comparison with those who covered military actions and events ashore. Civil War marine artists include Alfred R. Waud, Xanthus Russell Smith, and Conrad Wise Chapman. A member of that group, though generally unrecognized as such, is Robert Fulton Weir. While Weir did not leave behind a body of work that would make him prominent, he did illustrate scenes that depicted his personal observations of the sectional conflict.

A search for adventure spurred Weir early in his life. Born at West Point, New York, in 1836, he seemed to have all he would need for contentment. His father, Robert Walter Weir, was an accomplished Hudson River School landscape painter and served as a professor of drawing at the U.S. Military Academy for 42 years.

As an adolescent, Robert Fulton received artistic instruction from his father. Similar training allowed his younger brother, John Ferguson Weir, and half-brother, Julian Alden Weir, to become prominent artists. Sitting at an easel for many hours a week, however, was not what young Robert envisioned for his life. As a restless 15-year-old wanting adventure, he decided to run away to sea.

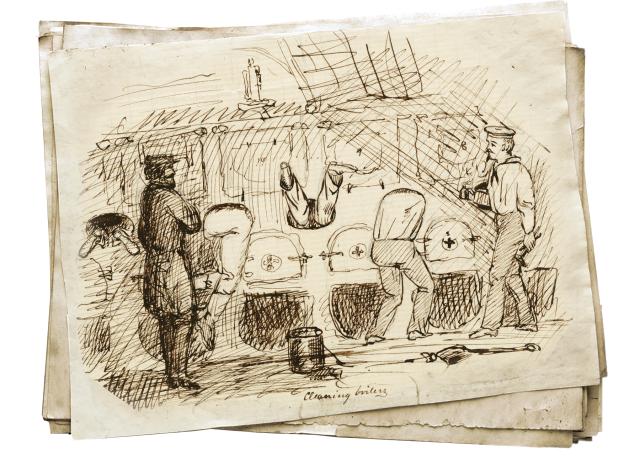

The teen traveled to Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, and signed on as a crewman on board the whaling bark Clara Bell. Wishing to leave his past behind, he assumed the name Robert Wallace and for the next 14 years sailed the world’s seas in search of whales. Between watches, he kept a journal that he generously illustrated with shipboard scenes and landscapes of the places his ships visited. He made his last cruise on board the whaling schooner Palmyra in 1862. With the Civil War already more than a year old, Weir decided to continue his life at sea by enlisting in the U.S. Navy.

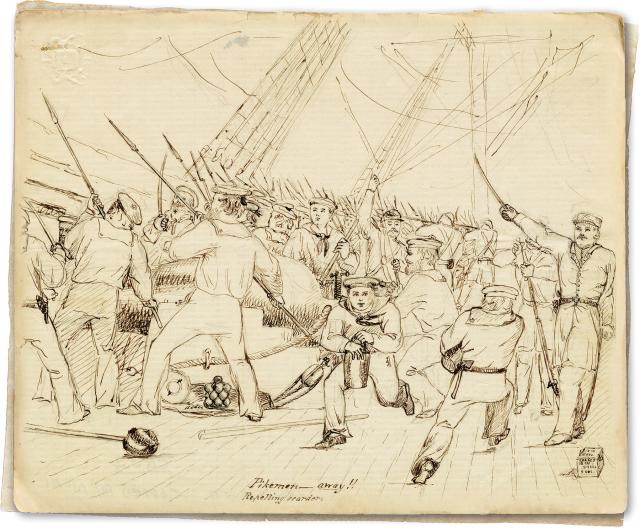

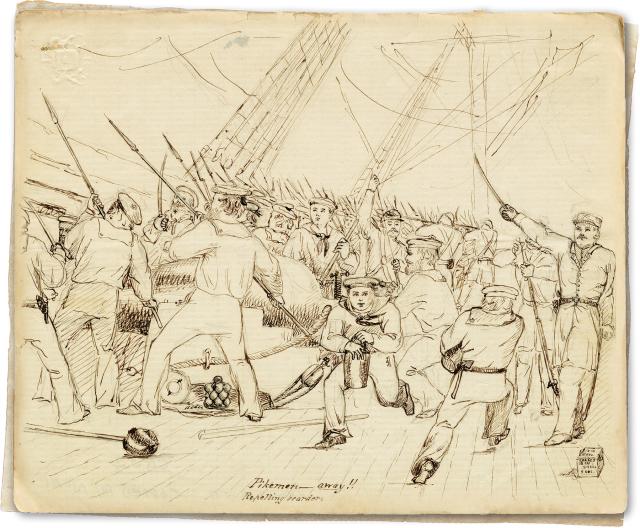

He signed on with the service on 25 August 1862 as an acting third assistant engineer. Weir was assigned to the 2,700-ton screw sloop Richmond, part of Rear Admiral David Farragut’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron. Having served only in merchant ships, he was struck by the impressive appearance of exercises on board the warship, such as gun and fire drills and practicing repelling boarders. He illustrated shipboard scenes and events and included some drawings in letters sent back to his wife, Daisy, and other family members. During the war, Weir also sent sketches to Harper’s Weekly, where they were published as wood-engraved illustrations for Navy-related articles.

The Richmond proved to be one of the most actively engaged warships of the squadron. As the junior assistant engineer, Weir’s battle station was at the bell pull on the bridge just forward of the mainmast. The pull sent signals to the engine room to regulate the ship’s speed.

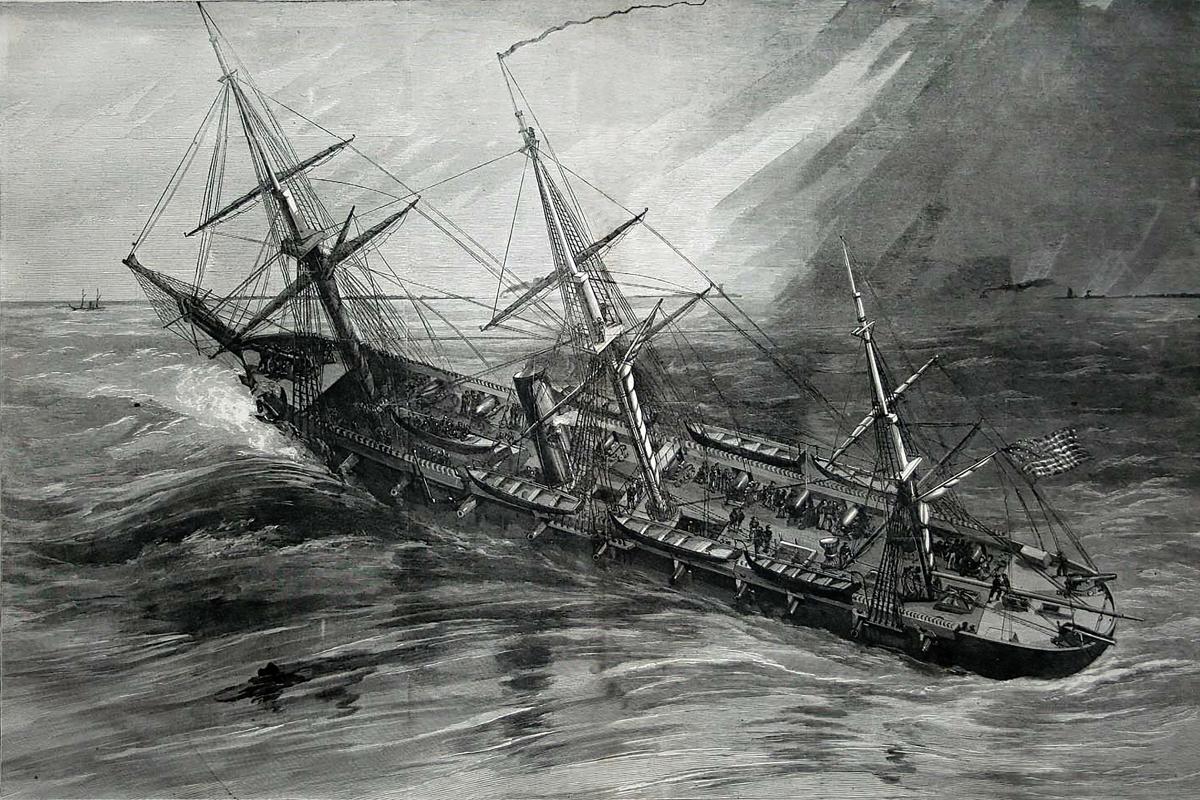

On 14 March 1863, Farragut sent his warships up the Mississippi River in an attempt to pass the Confederate batteries at Port Hudson, Louisiana. As they steamed upstream under heavy fire, Weir stood at the Richmond’s bell pull and assisted the ship’s captain, Commander James Alden, by pointing out the locations of the enemy’s batteries. During the battle, splinters and a piece of shrapnel struck the buckle of Weir’s sword belt, knocking him down and resulting in a painful but not serious wound. Alden helped him up, and he continued at his post.

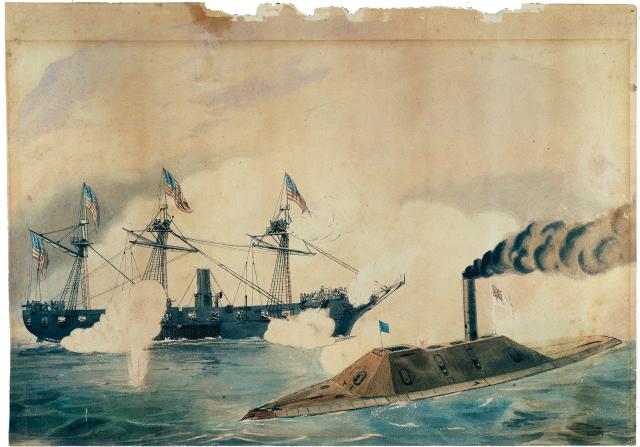

After duty on the Mississippi River, Weir was subjected to the monotony of the blockade, riding the swells off Mobile Bay, Alabama. After he was advanced to acting second assistant engineer on 20 February 1864, the tedium was broken when he participated in the 5 August Battle of Mobile Bay. He later used his artistic talents to create a rendering of the capture of the ironclad CSS Tennessee for the Navy Department. After the Richmond was ordered home, he resigned his commission on 19 June 1865 and was discharged that same day.

At nearly 30 years old, Weir decided to leave the sea behind. He continued to produce illustrations for books but made his living as an engineer. He was employed on two of the most important public infrastructure projects connected with New York City. He worked with the Union Subway Construction Company, which furnished below-ground utilities for the city, and also with the Croton Water Works, which supplied water to the metropolitan area. He died on 17 January 1905 at his home in Montclair, New Jersey, at age 69.

Sources:

Richard Rush et al., eds., Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894–1914).

Marian Wardle, ed., The Weir Family, 1820–1920: Expanding the Traditions of American Art (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2011).

“Robert Weir Dead,” The New York Times, 18 January 1905.

“Robert Walter Weir, Jr.,” Swann Auction Galleries, catalogue.swanngalleries.com/asp/fullcatalogue.asp?salelot=2241+++++288+&refno=642772&image=1.

Robert Weir Papers, Pearce Civil War Collection, The Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Corsicana, Texas.

Robert Weir Papers, G. W. Blunt White Library, Mystic Seaport Museum, Mystic, CT.

Robert Weir, Approved Pension Applications of Widows and Other Dependents of Civil War and Later, 1861–1910, Certificate 17195, M1279, National Archives, Washington, DC.