Even after eight decades, its immensity in every aspect defies the imagination. Operation Neptune to this day remains the largest amphibious assault in world history.

On 5 June 1944, an Allied fleet of 5,333 ships and landing craft emerged from a score of British ports for the overnight journey to the German-held coast at Normandy. Shepherded by thousands of Allied fighters and bombers, the seaborne armada carried an advance formation of 175,000 soldiers. Their cargo totaled 100,000 tons of equipment, including 50,000 vehicles ranging from jeeps to tanks.

Depending on the port of embarkation and the assigned landing beach, the trip ranged from 60 to 100 miles across the roiling dark water.1

Their D-Day mission the following morning was to land a spearhead assault force of 50,000 troops, penetrate Adolf Hitler’s Atlantikwall, and push the Germans back to allow the follow-on ground force of 41 Allied divisions to come ashore.

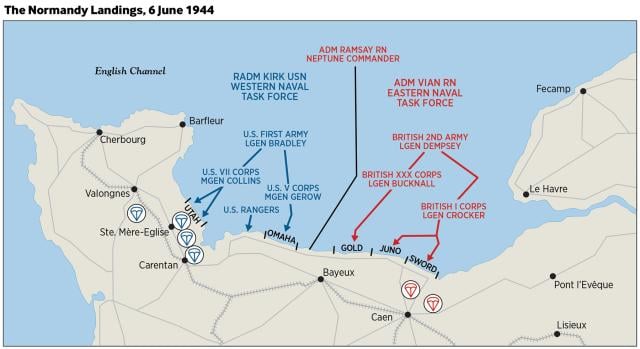

Their destinations were five designated invasion beaches interspersed along a 50-mile swath of the French coast. From west to east, three divisions of U.S. troops under the command of the U.S. First Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley would land at Utah and Omaha Beaches along the Cotentin Peninsula. The British Second Army—two British divisions and a Canadian division along with a 177-man Free French commando force—would come ashore immediately east of Omaha at three adjoining beaches—Gold, Juno, and Sword.2

Utah Beach—a late addition to the invasion plan—was a three-mile stretch of shoreline at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula just north of the Carentan Estuary. The 4th Infantry Division would land there.

Fifteen miles to the east, planners had designated the primary landing zone for two U.S. Army divisions. Omaha Beach comprised a six-mile length of the shoreline where the 1st Infantry Division and 29th Infantry Division would storm ashore.

The Allied objective was to hit all five beaches simultaneously at 0630 hours—just 22 minutes after sunrise—on D-Day, Tuesday, the 6th of June. Elements of the naval force for Neptune based in Northern Ireland and on the western coast of Scotland had been on the move since 3 June.

Planning for ‘Germany First’

Operation Neptune—the naval component and initial assault—and Operation Overlord—the overall invasion and Battle of Normandy—marked the culmination of four years of planning and debate among the Allied political leaders and military commanders. In early 1940, British and American military planners hammered out a basic strategy for defeating the Axis in the event the United States entered the war: Germany first.

The effort faced many challenges and several major setbacks from the beginning that delayed the invasion from 1943 to 1944. They included British losses of ships and men at Dunkirk, Norway, and Greece, the American struggle to create a Navy sizable enough to fight a two-ocean war, the U-boat threat in the Atlantic, and the effort required to create, train, and equip an army to carry out the fight.

Nevertheless, Allied military planners knew their only realistic chance of defeating Hitler remained to land several million troops in France and fight the German Army. In early February 1942, Dwight D. Eisenhower, then a relatively unknown U.S. Army brigadier general on the war plans staff, completed a strategic report that declared, “We should at once develop, in conjunction with the British, a definite plan for operations against Northwest Europe.”

The Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942 diverted most of the U.S. military forces that had deployed to the United Kingdom to date, as well as much-needed amphibious ships and landing craft. It was not until the Allied defeat of the German U-boat force in the North Atlantic in mid-1943 (see “From Crisis to Victory in the North Atlantic,” June 2023) that troops, ships, and equipment earmarked for invading the Continent began flowing across the Atlantic to the British Isles.

The formal decision to launch Operation Overlord/Neptune came at the end of 1943, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill met with Soviet leader Josef Stalin in Tehran, Iran. The Allied leaders agreed that the Americans and British would invade France in late May 1944, while the Red Army simultaneously would launch a major offensive against the Germans on the Eastern Front. By April 1944, the invasion force for Normandy was preparing for the fight.3

The military commanders appointed to lead Neptune/Overlord reflected the close Anglo-American partnership that had evolved. With Eisenhower named overall commander-in-chief, his two principal deputies were British General Bernard Law Montgomery as ground forces commander and Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay in command of the naval armada.

Historian Samuel Eliot Morison later described Ramsay, a 61-year-old veteran of World War I recalled to active duty in 1939, as “a remarkable character” whose prior experience in amphibious operations would prove vital at Normandy. In 1940, he had led the maritime evacuation at Dunkirk and later was deputy naval commander of amphibious forces in both Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa, and Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily.

Ramsay’s command was divided into two task forces responsible for transporting and defending the spearhead force. The Eastern Naval Task Force, under British Rear Admiral Sir Philip Vian, would transport the British and Canadian Divisions to Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches.

The senior U.S. Navy officer in Operation Neptune was Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk, commander of the Western Naval Task Force. He was charged with landing the 4th Infantry Division at Utah Beach and the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions at Omaha Beach. Kirk’s amphibious fleet was divided into “Force U” and “Force O” for the two landings. Rear Admiral Don P. Moon commanded Force U, while Rear Admiral John L. Hall led Force O. Commanding the naval bombardment group at Utah was Rear Admiral Morton L. Deyo. His counterpart at Omaha was Rear Admiral Carleton F. Bryant.

Like Admiral Ramsay, Kirk also was a seasoned veteran of earlier Allied amphibious landings. As a captain, he had served as naval attaché in London during 1939–41, before becoming director of the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) later in 1941. After a disagreement with newly appointed Navy Commander-in-Chief Admiral Ernest J. King and his deputies over managing ONI, Kirk joined the Atlantic Fleet, where he became commander of its amphibious forces. He led the eastern assault at Sicily.

Morison observed that Kirk’s prior wartime experience had prepared him well for serving as the senior American officer in Neptune/Overlord. “As naval attaché to the London embassy at the outbreak of the war in Europe . . . he had become thoroughly conversant with English ways, problems and personalities,” Morison wrote. “As Commander, Amphibious Forces Atlantic Fleet, he had made himself master of that branch of naval warfare.”4

By mid-May, the Neptune fleet was ready to carry the invasion force to France. After eight months of intense unit training and exercises, the Overlord force held full-scale landing rehearsals 27 April–8 May. Tragedy struck when German E-boats slipped into the landing area the night of 27–28 April, sinking two LSTs (landing ships, tank), damaging six others, and killing 749 crewmen and embarked soldiers. Nevertheless, the amphibious fleet was set.5

One thorny challenge for General Eisenhower was pinpointing the date and time of the invasion. Planners wanted to put the force ashore at dawn after a moonless night when the low tide was just starting to turn. Balancing moonlight conditions, the tides, and weather, they chose 5 June for D-Day, with 19–20 June as a backup.6

Allied commanders and intelligence officials were confident they could fool the Germans into thinking the invasion would occur at Pas-de-Calais, where the English Channel is at its narrowest, rather than at Normandy. A massive deception operation using dummy airfields and bases and a flood of fictional radio messages convinced the German High Command that a massive “First U.S. Army Group” under Lieutenant General George Patton was the designated spearhead to invade France. Not only did the deception work, but even after 6 June the German 15th Army—the mobile reserve force—remained pinned down at the Pas-de-Calais out of fear that Patton’s force was still planning to invade.7

The U.S. Navy’s Tenfold Growth

Operation Neptune was possible only because the U.S. Navy had grown tenfold in size in the 30 months since Pearl Harbor. It was a fleet expansion never seen before or since. On 7 December 1941, the Navy had only 337,349 active-duty personnel and 790 warships. That roster had grown to more than 2.8 million personnel and 6,084 ships worldwide by D-Day.

The Navy selected three of its oldest battleships for Neptune because they would be shooting their older 12- and 14-inch main batteries at the German defenses from virtually point-blank range. It was the same for the scores of 5-inch/38-caliber and 4-inch guns comprising the battleships’ secondary batteries and the main guns on board the destroyers.8

The bombardment task force for Operation Neptune would include 19 warships at Utah Beach under Rear Admiral Deyo: the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36) and the U.S. cruisers Tuscaloosa (CA-37) and Quincy (CA-71); the British cruisers HMS Hawkins, Black Prince, and Enterprise; the British monitor Erebus; and eight destroyers, two destroyer escorts, and two British frigates.

At Omaha Beach, Rear Admiral Bryant’s bombardment force included the battleships USS Texas (BB-35) and Arkansas (BB-33) along with the British cruisers HMS Glasgow and Bellona, the Free French cruisers Georges Leygues and Montcalm, ten U.S. Navy destroyers, and two Royal Navy destroyer escorts.

The Anglo-American landing force itself totaled nearly 3,000 ships and landing craft, the product of a crash construction program launched in 1942 in both countries. The American Western Naval Task Force comprised 931 ships and landing craft, while the Eastern Naval Task Force bearing British and Canadian troops totaled 1,796 ships and landing craft. The vessels ranged in size from the 328-foot oceangoing LST to the 35-foot landing craft, vehicle personnel (LCVP).

Minesweepers Lead the Way

A third, relatively smaller naval force would play an outsized role in the invasion. Throughout the 44 months of the war, the Germans had laid thousands of antiship mines in the English Channel. Both sides also had laid defensive minefields around their ports and harbors. Before Allied ground forces could land, clear transit lanes had to be created from British ports all the way to the Normandy beaches.

In the aftermath of the failed Allied raid at Dieppe in 1942, Hitler had ordered the construction of reinforced coastal defenses from northern Norway to the Franco-Spanish border. By late 1943, the effort had shifted to focus on the French coast. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the former commander of the Afrika Korps, led the effort. During the first four months of 1944, Rommel reinforced existing armored defensive positions and gun emplacements. He installed a half-million beach obstacles along the shoreline and expanded underwater defenses with steel beams, 12-foot-tall “Belgian Gate” barriers and “horned scully” barriers of steel beams in the form of a 12-foot-tall jack. Thousands of the beach obstacles were armed with Teller antitank mines or artillery shells.

Rommel also added to the existing minefield running along the central axis of the English Channel and laid new minefields just off Normandy and the Pas-de-Calais. In addition to older, moored mines and magnetic and acoustic mines on the seabed, the Germans deployed a new type of seabed pressure mine that would detonate from the change in water pressure as a ship passed over it. The Luftwaffe air-dropped 4,000 of these mines in the Bay of the Seine.9

With antiship mines the primary German defensive weapon, the “terrifying honor”—in one historian’s words—of leading Operation Neptune to France would go to an Anglo-American fleet of 245 wooden-hull minesweepers. To create a cleared channel, groups of a dozen minesweepers would steam in an echelon formation trailing their sweep cables astern and set to a preset depth by paravanes to sever the mooring chains anchoring the mines beneath the surface. Any that were cut free would be detonated by small-arms fire as they bobbed to the surface.

There were three stages to the minesweeping mission. First, the wooden vessels would create swept channels from each of the southern U.K. ports to the main rendezvous at “Point Z,” a marshaling area five miles in diameter located 13 miles southeast of the Isle of Wight. From there, they would next clear five channels—one for each of the five invasion beaches—running south from Point Z toward Normandy. At the halfway mark, each lane would widen into two distinct pathways—one for fast convoys and the other for slow convoys—ending at each of the five transport assembly areas about ten miles offshore. These channels were 400 yards wide and marked with lighted buoys at one-mile intervals. The minesweepers’ final task was to clear the transport anchorages and sweep two fire-support channels and anchorages for the bombardment warships just eight miles off each of the invasion beaches. After that, they would form a defensive perimeter offshore.

The fleet following in the minesweepers’ wakes was beyond measure. Force U, assigned for Utah Beach, consisted of 12 separate convoys of troopships, supply ships, and landing craft. Force O, bound for Omaha, proceeded in nine convoys. The British Second Army, organized in three separate transportation groups, would require 38 convoys to ferry the troops to their three invasion beaches.10

Launching Operation Neptune

On Sunday, 26 May, Admiral Ramsay issued the message: “Carry out Operation NEPTUNE.” Armed guards sealed the crews in their ships and landing craft. From their guarded encampments throughout southwest England, American units began moving toward their assigned ports. By 3 June, the armada was ready and began streaming out into the Channel—only to be abruptly ordered to return because of deteriorating weather conditions.

Finally, at 0415 hours on Monday, 5 June, upon receiving a weather prediction that conditions at Normandy would ameliorate by the next day, Eisenhower made the decision: “O.K. We’ll go.” Overlord/Neptune was on.11

One of the minesweepers would have the dubious honor of sustaining the first combat deaths of Neptune/Overlord. The USS Osprey (AM-56) and her crew were hardened veterans by D-Day. Commissioned in late 1940, the 220-foot ship displaced just 1,040 tons and was armed with one 3-inch cannon and a pair of 40-mm antiaircraft guns. But her 105-man crew had served on coastal patrol in the western Atlantic and escorted U.S. forces ashore in North Africa.

Two hours and 15 minutes after Eisenhower’s order went out, the Osprey and nine other vessels from Mine Squadron 7 departed port at 0630 and began sweeping operations. Eight steamed in echelon, with their cables overlapping the ship astern, while the other two deployed lighted buoys marking the channel boundaries. A Royal Navy motor launch followed behind to sink any surfaced mines. After sweeping its assigned Channel convoy lanes, the squadron’s second task was to clear a channel and the six-by-six-mile Fire Support Area One at Utah Beach, where the the Nevada, Quincy, and Tuscaloosa would anchor for the bombardment.

The minesweepers had reached a point ten miles below Point Z by 1755 and were passing a slow troopship convoy when the Osprey struck a mine. The blast shattered her hull, blowing a large hole in the forward engine room, and killed six crewmen. The survivors abandoned ship and were picked up by another minesweeper. The rest of the squadron continued the slow march to Normandy, and by 2300 were beginning to clear the fire-support anchorage. Overhead, the sailors could hear the loud drone from more than 850 C-47s dropping 13,000 paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions onto the Cotentin Peninsula.12

The Channel crossing largely proceeded as planned, with waves of landing craft, large amphibious vessels, troopships, and the bombardment warships forming up in order at Point Z, then entering their assigned channels to proceed south. While soldiers on the large troopships enjoyed a warm and dry trip, those on the smaller landing craft were soaked by the previous two days of rain and seasick from the rough, 20-foot Channel waves that violently battered their craft.

Opening Fire at Utah

The bombardment ships for Force O and Force U reached station just after midnight on 6 June. The battleships and cruisers were anchored in the fire support areas about six and a half miles offshore, while the destroyers took station three miles closer in. Their initial targets were several dozen German artillery emplacements, including ones at Pointe du Hoc believed to house six 155-mm guns that could range on both Omaha and Utah. The bombardment at Utah began 20 minutes early when, at 0536, a coastal battery opened up on two destroyers, the USS Corry (DD-463) and Fitch (DD-462), along with several of the minesweepers working offshore.

The bombardment ships quickly returned fire. As planned, the battleships and cruisers fired their big guns at preselected targets on the beach or inland, while their rapid-fire secondary guns joined the destroyers in drenching the two landing beaches with high explosives.

At that moment, a random battlefield event doomed the Corry: At 0610, support aircraft began laying smokescreens in front of the five destroyers, but the plane assigned to the Corry was shot down before it could act. The other four destroyers vanished in the smoke, leaving the Corry as the only visible target. Desperately maneuvering to avoid being hit, the destroyer veered out of her swept channel and set off a mine that tore the 1,630-ton warship in half. Lieutenant Commander George Dewey Hoffman ordered his crew to abandon ship. The survivors clung to floating wreckage for several hours under a hail of German shells before being rescued. Thirteen of the 276-man crew were killed.

For the rest of the bombardment force, the battle continued unabated. The Nevada gunnery sailor Dick Ramsey later recalled, “We would remain at our battle stations, shelling targets as close as the beach seawall and as far as 17 miles inland, for the next 80 hours.” On the first day alone, the Nevada’s 14-inch/45-caliber main battery fired 377 rounds at German targets; the battleship’s 5-inch/38-caliber gun crews lobbed 2,693 rounds at the enemy.13

The Best-Laid Plans . . .

The actual landings at Utah and Omaha Beaches had starkly different results. In both cases, the detailed operational plans disintegrated from the outset in the fog and friction of combat.

Plans for both American invasion beaches were detailed and marked down to the minute beginning at H-Hour. At Omaha, the first force ashore would be eight LCT landing craft bearing a total of 32 M-4 Sherman tanks, along with another 32 amphibious DD Shermans beaching under their own propulsion after driving into the water from their landing craft 5,000 yards offshore. This light armored force would spearhead the ground attack.

At H+1—exactly one minute later—four infantry companies from the 1st and 29th Divisions were scheduled to land on their four designated beach zones, each carried by six LCVPs bringing them in from the troopships ten miles offshore.

At H+3, two minutes after the infantry, a dozen LCM “Mike” boats were to land bearing “Gap Assault Teams” (GAT) of Army combat engineers and Navy Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) frogmen. Their mission was to blast clear lanes through Rommel’s forest of concrete and steel obstacles.

Within the first 60 minutes after H-Hour, five more waves of landing craft were to arrive, bringing in the remainder of the two divisions and a host of support troops. An identical planned flow of men and gear would occur at the other beach.

Neither plan survived first contact with the enemy.

At Utah Beach, an unexpectedly strong current running north to south swept the initial wave of landing craft nearly a mile away from their assigned zones. More confusion came with the sinking of several control craft whose mission was to keep the landing waves in order and headed to the correct beach. Still, the leading 4th Division units had a relatively unscathed landing, and two dozen succeeding assault waves came ashore with few casualties.

Not at Omaha Beach: The initial waves of troops entered a slaughterhouse. Hung up on the obstacle belt, the troops were decimated by the German fire. Struck by a German 88-mm shell, one landing craft carrying troops from Company A of the 116th Regiment was hit and vaporized, killing all 36 men on board. At day’s end, only 24 of the company’s 200 soldiers were still alive, and most of them were wounded.

While the Germans suffered a massive intelligence failure by not identifying Normandy as the Allied target, the Allied intelligence failure at Omaha was almost as severe. Planners had estimated that only a single battalion of 700 second-rate German troops were guarding the beach. Instead, the combat-hardened 352nd Infantry Division had three battalions dug in and waiting. Second, the plan called for a massive aerial bombing of the German emplacements, but a low cloud cover obscuring the targets caused the bombers to miss.

The mission to blast gaps in the mined obstacle belts went to the GAT teams, each of which had six frogmen and 27 Army combat engineers. Each team’s task was to clear a 50-yard opening in the obstacle belt. Sixteen GAT teams came ashore at Omaha Beach. But trapped in the same withering fire that massacred the troops preceding them on shore, the GATs could clear only five of the 16 gaps assigned to them, while suffering 31 killed and 60 wounded—a 70 percent casualty rate. One team was wiped out to a man when the rubber boat carrying 300 pounds of high explosives took a direct hit. A second vanished when the explosives they were setting were hit by gunfire.

George Morgan, a UDT sailor at Omaha, described the mission failure years later: “Because the water coming crossing the Channel was so bad, so rough, they lost practically all of their explosives . . . they had nothing to work with, plus the fact that the one big mistake they made was these [teams] should have gone in before the invasion rather than with the invasion because a lot of GIs were hiding behind the stuff we were supposed to blow up.”14

A Hard-Won D-Day Victory

In the end, the Allies prevailed by pure grit, bravery under fire, and the sheer mass of the landing force. When the sun went down at 1745 hours on 6 June 1944, the Neptune fleet had put nearly 175,000 Allied troops ashore. They had broken through the German defenses and clung to a toehold along the 55-mile invasion front. The British and Canadians had advanced six miles inland, while the Americans were holding on to a narrower stretch that at Omaha was only one mile deep.

That initial victory did not come cheap. A total of 4,414 Allied troops perished on D-Day, including 2,501 Americans. Another 5,000 were wounded in the fighting.

The minesweepers cleared more than 800 mines from the waters off Omaha and Utah, but still there were losses. Besides the Corry, the U.S. Navy lost a second destroyer, a destroyer escort, two minesweepers, and 43 large and medium landing craft, all but a few due to unswept mines. However, total U.S. Navy casualties were light with about 200 killed.15

Senior commanders credited the naval gunfire support at Utah and Omaha with playing a pivotal role in the eventual success of D-Day. Equally vital to that success was the performance of hundreds of sailors who manned the landing craft carrying their Army comrades ashore and retrieving the wounded for medical care. Rear Admiral Kirk, commander of the Western Naval Task Force, stated, “Our greatest asset was the resourcefulness of the American sailor.”

Stepping ashore at Omaha Beach late on D-Day, Major General Clarence R. Huebner, commander of the 1st Infantry Division, sent a message back to First Army commander General Omar Bradley on board the USS Augusta (CA-31): “Thank God for the United States Navy!”16

1. Stephen E. Ambrose, D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 140; Samuel Eliot Morison, The Two-Ocean War (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962), 391–93.

2. Ambrose, D-Day, 140; Norman Polmar and Thomas B. Allen, World War II: America at War (New York: Random House, 1991), 586–88.

3. Morison, Two-Ocean War, 14, 22–24; Ambrose, D-Day, 65.

4. Morison, Two-Ocean War, 29–30; Polmar and Allen, World War II, 474–75.

5. Ambrose, D-Day, 136.

6. Ambrose, 86–88.

7. Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 11, The Invasion of France and Germany, 1944–1945 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1957), 74.

8. FADM Ernest J. King, USN, U.S. Navy at War, 1941–1945: Official Reports to the Secretary of the Navy (Washington, DC: U.S. Navy Department, 1946), 15–18.

9. Morison, History of United States Naval Operations, 44–46.

10. Joshua Schick, “The First Ships of Operation Neptune,” posted at “D-Day and the Normandy Campaign,” nationalww2museum.org; Morison, History of United States Naval Operations, 77.

11. Morison, History of United States Naval Operations, 82–83.

12. Schick, “First Ships.”

13. Morison, History of United States Naval Operations, 95–97; Guy Nasuti, “Operation Neptune: The U.S. Navy on D-Day;” and Dick Ramsey, “Reflections of a Battleship Sailor.”

14. Ambrose, D-Day, 322, 326; Polmar and Allen, World War II, 588.

15. “Allied Ships Sunk,” uboat.net.

16. Ambrose, D-Day, 152.