Operation Neptune witnessed the largest naval armada ever assembled in the history of warfare. (See “The Invasion Fleet that Liberated Europe,” pp. 28–35.) Among the hundreds of warships, junior officers and enlisted crews in the smallest vessels played the critical role of guiding the invasion landing craft ashore. Recently, the photographs and documents of one sailor became known—a man who played witness to history at Utah Beach.

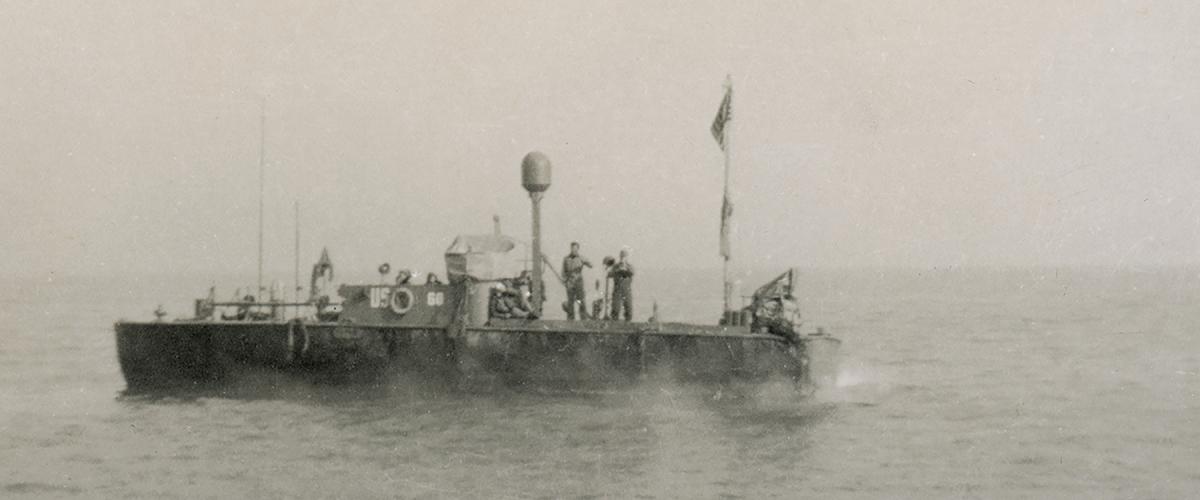

To guide U.S. ground forces to their respective sectors of Utah and Omaha Beaches, the Navy employed specialized vessels termed landing craft, control (LCC). After guiding landing craft to their respective beach sectors, the LCCs would provide traffic control for ensuing landing waves.

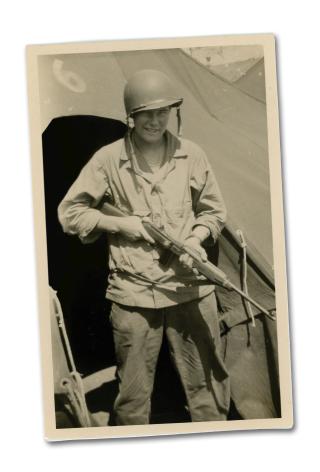

One of these craft slated for the invasion was LCC-60. Naval Reserve Lieutenant (junior grade) Howard Vander Beek, a 26-year-old from Iowa, commanded the vessel. Earlier, he had participated in Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, in July 1943. Among Vander Beek’s crew for Operation Neptune was radioman Howard Taylor “Bud” Lovrien, also of Iowa (shown in the photo below).

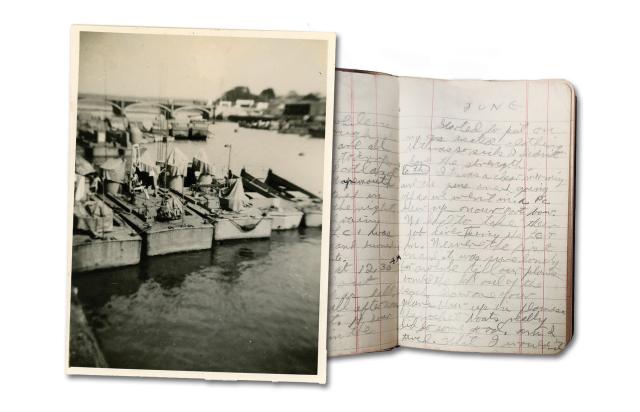

On the eve of the fateful events about to unfold at Normandy, Lovrien recorded in his diary: “Rough as hell. I threw up all afternoon. It’s cold & wet. H-hour is at 0630 in the morning. Started to put on my gas-treated clothing but was so sick I didn’t have the strength.”

On D-Day, 6 June 1944, Vander Beek had orders to move LCC-60 into position to provide backup to the primary control ship and guide landing craft to the Tare Green sector at Utah Beach for the appointed time, 0630, to begin the naval invasion.

As they waited, Vander Beek and his crew heard enemy shell fire directed at them. Suddenly, at around 0540, the primary control vessel for the adjacent “Uncle Red” sector sank—victim of an enemy sea mine. Moments later in LCC-60’s section, a landing craft carrying a load of tanks struck a sea mine and sank. Meanwhile, a deafening roar swept over the invasion area as U.S. bomber aircraft hammered the invasion beaches. Naval gunfire erupted 20 minutes later, with dust and smoke soon enveloping the entire coastline ahead of LCC-60.

Around this time, Lovrien received and decoded a message for Vander Beek reporting that his craft’s counterpart in the Uncle Red sector, LCC-80, was unable to maneuver after a buoy line fouled the propeller. The primary control ship for Tare Green directed LCC-60 to shepherd all the invading craft to shore in the Uncle Red sector while continuing to provide support for the Tare Green sector.

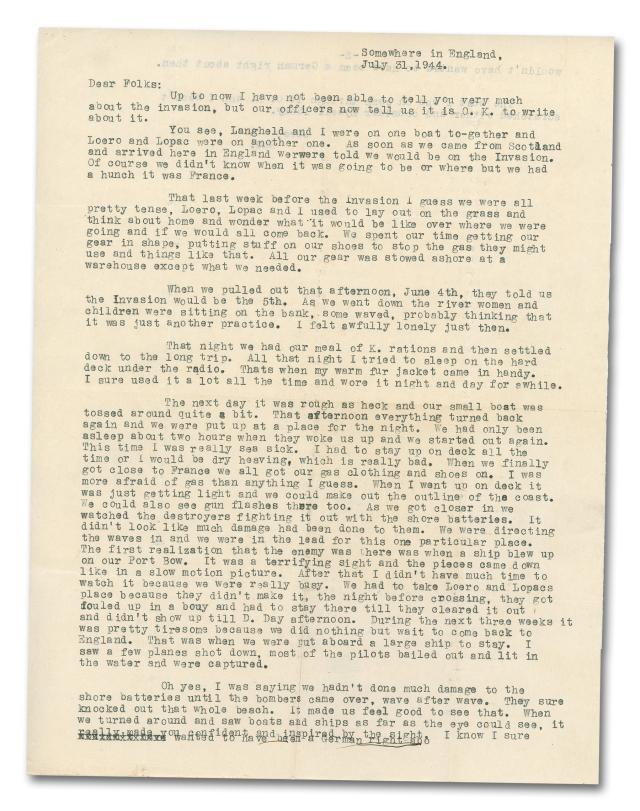

As the sun began to rise, Vander Beek turned to see what he called “the greatest armada the world had ever known, the greatest it would ever know” behind him. In his diary, Lovrien wrote, “We were the first in and it was sure lonely for a while till our planes bombed the hell out of the beach.” In a letter home to his family dated 31 July, Lovrien offered additional details, writing:

When I went up on deck it was just getting light and we could make out the outline of the coast. We could also see gun flashes there too. As we got closer in we watched the destroyers fighting it out with the shore batteries. It didn’t look like much damage had been done to them. We were directing the waves in, and we were in the lead for this one particular place. The first realization that the enemy was there was when a ship blew up on our port bow. It was a terrifying sight and the pieces came down like in a slow-motion picture. After that I didn’t have much time to watch it because we were really busy.

LCC-60 helped move the LCTs (landing craft, tank) closer at Uncle Red and Tare Green. She then turned to control duties in Uncle Red sector, directing waves of tanks and men ashore.

Unbeknownst to the men of LCC-60, the combination of limited visibility and a strong ocean current and winds caused the first wave of landing craft they directed to come ashore approximately 1,000 to 1,500 yards south of the intended landing zone. Fortunately, this section of the beach had few obstacles and even fewer defenders. Among the men landing on that section of beach was Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr., assistant division commander of the Fourth Infantry Division. He scouted the landing area and, after finding the location feasible, declared, “Get the word to the Navy to bring them in. We’ll start the war from right here!”

LCC-60 was relieved of her duties around 1400 hours. Vander Beek was summoned to brief the senior leaders and war correspondents on the landings at Utah. After answering their questions, he returned to LCC-60 and spent the remainder of the day shuttling personnel from ship to ship. His crew spent the evening on board an LST (landing ship, tank), grabbing a hot meal and sleep while rotating in three-man shifts on two-hour watches on board the cramped LCC-60.

After D-Day, Vander Beek again captained LCC-60 in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France. When he left LCC-60 in late 1944, he took her flag that had flown at Normandy and southern France home with him. (The photo below of LCC-60 shows her flying this selfsame flag.) The worn flag remained in his custody until sold at auction in 2015. In 2019, Bert Kreuk and Theo Schols, the owners, donated the flag to the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. Then, in 2023, the Lovrien family graciously donated Bud’s diary and photographs to the museum as well—where they join LCC-60’s flag in memory of those men who helped first breach Adolf Hitler’s Atlantic Wall.

—Frank Blazich Jr., Curator of Military History, National Museum of American History