When William Faulkner famously wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” he could have been describing my wartime service on board the USS Nevada (BB-36).

Even though it has been 80 years since I reported aboard the battleship at San Francisco in 1943, my memories of the major battles the Nevada fought in World War II remain as vivid as if they happened yesterday.

I had the privilege of serving on a U.S. warship that served in every major theater of the war. She was the only battleship that was able to get underway during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Although severely damaged by a torpedo and five bomb hits that sparked a major fire belowdecks and killed 60 crewmen, the Nevada nevertheless was repaired, modernized, and returned to service in just ten months. She had just returned from her first wartime mission bombarding Japanese positions on Attu in the Aleutians when I reported aboard at San Francisco in late May 1943. I was one of 200 freshly minted sailors who had crossed the country by train from boot camp at Great Lakes, Illinois.

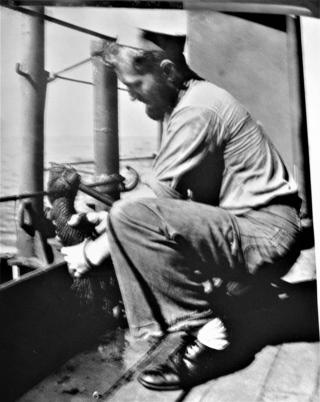

Looking back, I realize that my family history likely preordained that I would join the Navy. My great-grandfather, Frank Ramsey, was a boilermaker and pipefitter at the Continental Iron Works shipyard in Brooklyn. He was one of the shipwrights who built the ironclad Monitor for the Union Navy in the fall and winter of 1861. One of my uncles, Joseph Ramsey, had made a career in the Navy at the turn of the 20th century, rising to the rank of chief petty officer, but, while serving in World War I, he tragically died of the influenza pandemic that swept across the United States and Europe in 1918. And my father, Frank Ramsey, served in the U.S. Army in France.

Well before Pearl Harbor, I was employed at the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a pipefitter’s helper. There, I had my introduction to battleships. Prior to my enlistment in the Navy in March 1943, I worked on the construction of the USS Iowa (BB-61) and Missouri (BB-63) and did repair work on the South Dakota (BB-57).

When I enlisted in the Navy, I was a wiry five-foot-six recruit weighing 142 pounds. During ten weeks of intense physical training at Great Lakes, I gained 20 pounds while mastering the basics of sailor life: close-order drill, calisthenics, classroom instruction memorizing The Bluejacket’s Manual, swimming, firefighting drills, and loading dummy 5-inch shells into mockup naval guns. From the moment I had decided to enlist, my goal was to serve in submarines. However, the Navy had other plans; I left boot camp a seaman with orders to the Nevada.

Arriving by bus at the Bethlehem Steel Company Shipyard on San Francisco Bay, I had my first glimpse of the Nevada. She looked to be the largest ship any of us had ever seen. Still clinging to the fading hope that my orders would send me to a submarine squadron, I turned to the grizzled chief petty officer in charge of our group and muttered, “That’s not a sub.”

“Oh, a smart one,” the chief said.

I quickly discovered that I and the other newcomers were part of a major “lesson learned” from Pearl Harbor. When the Japanese aircraft struck, the Nevada had 12 5-in./51 cal. and eight 5-in./25 cal. antiaircraft guns – installed in open gun bays abovedecks unprotected by turrets. Despite shooting down at least four attackers on December 7, naval engineers immediately realized that the Nevada and other surface warships needed a more robust air defense. While undergoing repairs and modernization at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, shipwrights added 16 powerful Mk-12 5-in./38-cal. guns to the ship, mounted in eight twin-barrel turrets installed four to each side amidships.

I was assigned to the 9th Division under the command of Lieutenant R. C. Brandt, with two other officers, Lieutenant Ed Swaney and Ensign Runza, supervising 140 men. We were responsible for manning the four guns in mounts 1 and 3, the forward-facing turrets on the Nevada’s starboard side.

During General Quarters, one of our officers manned the “Sky One” fire control turret that directed the two mounts. We enlisted men manned the turrets and ammunition hoists.

The ship soon received orders to the Atlantic Fleet. Standing procedure required that all guns be manned around the clock. That meant there were four crews of between 13 and 14 men assigned to each of the four guns that 9th Division operated. In total, the installation of the 16 5-in./38-cal. secondary battery added nearly 400 more sailors to the ship’s crew, raising it to a total of 2,220 officers and enlisted men.

She was a pretty crowded ship, and there was even less elbow room in the cramped 5-inch gun turrets when we manned them for practice or combat.

As I would learn during countless hours of training and gunnery practice, the 5-in./38-cal. was an excellent dual-purpose gun. We could shoot a 55-pound shell out to 18,000 yards against surface targets and engage aircraft flying up to 37,000 feet.

It took a full team to operate each Mk-12 gun. Leading the gun mount was the mount captain, a senior petty officer. He sat on an elevated seat at the rear of the turret, where he could monitor both gun crews in action. Wearing a sound-powered telephone, he would receive orders from the battery commander in Fire Control, and transmit situation reports on each gun’s status. The twin guns inside each turret sat side by side about four feet apart.

In front of him, nine sailors operated each of the two Mk-12 guns. On one side of the rammer that extended to the rear of the gun breech, the gun captain, a petty officer, oversaw the crew as they trained the gun, loaded powder cases and projectiles, and actually fired it when under “local” control (most of the time, the gun was placed on “auto fire” status, where the officer manning Sky One actually aimed and fired, either one or more turrets simultaneously).

The other eight men manning each of the Mk-12s in the turret serviced the gun itself. Sitting in the left front corner of the mount, the pointer controlled the gun’s elevation and, when in local control, actually fired the gun by rocking a foot pedal connected to the firing pin in the breech. The trainer, sitting in the right front corner, directed the gun’s azimuth bearing. The sight setter, standing just behind the trainer, operated the optical sight system to aim the gun while in local control, and to match the transmitted information from Fire Control when in automatic mode.

The fuze setter operated the equipment that set the arming time on projectiles with mechanical time fuzes. The powder-man and projectile-man loaded the gun. First, the powder-man placed the powder case on the rammer tray. Next, the projectile-man lifted a 55-pound shell out of the ammunition hoist, placed it in front of the powder case, and then pulled the rammer lever to insert both the powder case and projectile into the gun. Once fired, the hot case man would catch the empty powder case when it was ejected from the gun and throw it outside the mount.

That wasn’t all. When not on duty in the turret, each of the four crews assigned to each gun would rotate working in the upper handling room one level below, feeding projectiles and powder cases up to the gunners. A second group worked far below on the third deck in the 5-inch ammunition storage magazine for mounts 1 and 3, loading shells and power cases onto the conveyor belts. During my first taste of combat at Normandy, my crew and I were assigned to work in the powder magazine four decks down, working alongside the mess attendants from SM Division. We fed 5-inch shells and powder cases to the conveyor belts that carried them to the handling room, where they were loaded into the hoists to keep the mounts loaded with powder and projectiles.

We would all become cross-trained in the individual gun crew positions, and during extended firing, would swap out every four hours.

Once on board the Nevada, it was on-the-job training from day one. I was initially assigned as a powder-man in mount 3. The around-the-clock gunnery drills were exhausting, but the intense training paid off. We became proficient enough that in engaging surface targets, we could fire 26 rounds per minute—just over two seconds for loading and firing. Firing in antiaircraft mode was more difficult, because when the guns were elevated, it depressed the breech and loading mechanisms and forced us to load the shells and powder from an awkward angle.

One surprise I discovered was that while abovedecks the sound of main and secondary gun batteries firing simultaneously was deafening, this did not penetrate the turret. When we fired a round, the noise went out of the turret through the barrel. Still, those of us working inside became robots after a while.

Leaving San Francisco Bay in June, we continued our gunnery training as the Nevada proceeded south to the Panama Canal and crossed the Caribbean en route to Norfolk. After a brief overhaul at Norfolk Naval Shipyard, we began a ten-month stint on Atlantic convoy duty, criss-crossing the Atlantic with large groups of Allied merchant ships. As we later learned, the U-boat menace had been largely thwarted earlier that spring in several massive battles where Allied escort ships and aircraft drove them from the North Atlantic. However, the admirals feared that Germany might still unleash surface raiders to attack the merchantmen, and the Nevada was there as protection. They never did come out.

Despite the long days at sea, we still had many opportunities for liberty during port visits, In San Francisco, I literally ran into my older brother, Frank Ramsey, on the street. He also had joined the Navy and was a Naval Armed Guard gunner assigned to an Occidental Corporation fleet tanker. Later on, we visited ports in England, Scotland, Ireland, Algeria, and Italy.

Our ten-month Atlantic intermission ended in April 1944, when the Nevada left Norfolk for the United Kingdom to prepare for the Allied invasion of Normandy. We began practicing shore bombardment along the Firth of Clyde on the west coast of Scotland. Lieutenant Brant briefed us that the terrain there resembled the coast of France along the Cotentin Peninsula where the invasion was set to take place.

In early June, we went into combat. Departing Bantry Bay in Northern Ireland, Fire Support Unit One included the Nevada, six cruisers and 12 destroyers and frigates assigned to bombard German defenses at Utah Beach. Confronting us would be a sizable shore-based German artillery force including more than two dozen 77-mm. and 6.1-inch naval guns mounted in seven-foot-thick reinforced emplacements. Another priority target was an immense concrete seawall blocking passage off Utah Beach.

It was dark and quiet, but the tension gripped us all as the Nevada dropped anchor 90 minutes after midnight on Tuesday, 6 June 1944—D-Day. We were in position about 11,000 yards offshore between the heavy cruiser USS Quincy (CA-39) and the destroyer Butler (DD-636). Because the Nevada was keeping her starboard side facing the shore, the portside ammunition magazine was closed. An hour later, we went to General Quarters. At 0536 we heard the order to open fire from the Nevada’s executive officer, Commander Howard Yeager. The Nevada had the honor of firing the first salvo. Down below in the magazine, it was like someone beating on the bulkhead with a hammer.

We would remain at our battle stations, shelling targets as close as the beach seawall and as far as 17 miles inland, for the next 80 hours. On the first day alone, our 14-in./45-cal. main battery fired 377 rounds at German targets; the 5-in./38-cal. gun crews lobbed 2,693 rounds at the enemy.

Aided by airborne spotter planes and ground-based fire controllers, our accuracy was unmatched. At one point early on, a spotter plane radioed the ship that a formation of German tanks was threatening a U.S. airborne position miles inland. Our guns immediately devastated the enemy armor. Two days later, the ship crushed another German force, destroying 90 tanks and 20 trucks on the road to Cherbourg.

The Germans at Utah Beach fought back, although hopelessly outmatched by the naval bombardment force and more than 2,200 Allied bombers assigned to our sector. During our Normandy mission, we were straddled by German shells 27 times; fortunately, none ever hit. I would not come face-to-face with the horror and gore of combat until seven months later.

After Normandy, the freshly refitted Nevada passed through the Strait of Gibraltar for a second front against Nazi-occupied France. For 18 days beginning on 15 August, we fought alongside battleships USS Arkansas (BB-33) and Texas (BB-35) in Operation Dragoon, the invasion of Southern France. Our guns destroyed a number of heavy gun emplacements defending the port of Toulon. The Nevada was ordered to destroy the French battleship Strasbourg, which was down at the stern moored in port. Then on 2 September came orders to return to the U.S. East Coast for upkeep, modernization, and repairs. We received several 14-inch main battery gun barrels from the USS Arizona (BB-39) and Oklahoma (BB-37).

Back on the West Coast, we spent a week firing at shore targets at San Clemente Island. Then, after a two-day pre-Christmas break with liberty in Long Beach, we got underway, heading west. Our destination was a small island in the western Pacific called Iwo Jima.

Over the years, I’ve told people who asked about how I coped during my wartime service: My shipmates and I took it one day at a time. We were a bunch of kids I’d say . . . we knew nothing and we feared nothing. That ended for me on 17 February 1945.

It was D-2 for the Marine assault on Iwo Jima, the ash-covered rock several hundred miles south of the Japanese Home Islands. The Nevada was the bombardment task force flagship for a fleet of seven battleships, eight cruisers, and a half-dozen destroyers. As at Normandy, we were proud to fire the first shot in the pre-invasion barrage.

We had begun a sustained shelling of the entire island the day before, but initially the concealed Japanese gunners had resisted the urge to fire back. However, when a group of 16 LCI landing craft approached the shoreline to drop off some frogmen to survey the beach terrain that morning, a hidden gun emplacement raked them with gunfire. Three LCIs were sunk, and the others riddled with shellfire. Seeing the carnage, Captain Homer L. Grosskopf ordered the Nevada to close with the beach, with every possible gun blasting away at the suddenly revealed enemy gun emplacement. At one point, our 5-inch mounts were firing more than 200 shells per minute.

I was handling ammunition on deck when the call rang out for stretcher bearers. I saw several damaged landing craft heading toward the Nevada, and as they drew close a number of severely wounded men were visible. Carefully, a group of us, including Lieutenant Swaney, lowered basket litters with a winch and hauled each casualty up to the main deck, and then hustled them below to the casualty station. We removed five dead and 20 wounded sailors from the small craft, two of whom died on deck.

It was a sobering moment for me. We didn’t see much blood and guts inside a battleship.

As at Normandy and Southern France, the Nevada’s gun crews were at General Quarters practically 24 hours a day. During the three-day pre-invasion bombardment, direct gunfire support on D-Day and for two days afterward, our secondary battery of 16 Mk-12 guns fired 4,689 rounds at targets ashore. We would remain off “Sulphur Island” until 8 March, when the fighting was all but over.

The worst was still to come. We had a forewarning three days later when the ship was at anchor at Ulithi Atoll. We had had a few hours of recreation on Mog Mog Island, and back on board were enjoying a movie on deck when the projector failed, pitching us into darkness. It was a fortunate glitch—for at that moment, a Japanese kamikaze dive bomber flew overhead and dove into the aircraft carrier USS Randolph (CV-15), anchored a ship’s length ahead of us. A huge fireball rose into the sky. Later, we heard that 27 men had died and 105 were wounded, including four who later died on board a hospital ship.

On 21 March, Task Force 54, including the Nevada, departed the Caroline Islands for the invasion of Okinawa. Our bombardment force included ten battleships, ten cruisers, and two dozen destroyers. We arrived in Okinawan waters on Sunday, 25 March, six days before the 1 April amphibious landings were to occur. Two days later, a kamikaze Val dive-bomber, struck by our antiaircraft batteries and afire, still succeeded in crashing into turret 3 aft. The blow knocked out the two 14-inch guns and destroyed three 20-mm. mounts, killing one officer and ten shipmates and wounding 49 others. For the first time since Pearl Harbor, the Nevada became a scene of death and destruction.

Nine days later, the Japanese struck again, and this time for me, death passed very close by. My gun crew and I had just been relieved from duty, and I was just getting comfortable in my bunk when the General Quarters alarm went off. I jumped up and ran for my GQ station. Several minutes later, a previously undetected 6-inch Japanese artillery piece ashore fired five rounds that struck the ship on the starboard side. One shell penetrated five bulkheads and passed directly through my bunk on the second deck. I was lucky; that barrage killed two shipmates and wounded another 17 men.

Both the invasion of Okinawa and the nightmare of massed kamikaze attacks went on for what seemed to us an eternity in hell. The slaughter on land and at sea continued for 82 days as a half-million U.S. Marines and soldiers fought more than 100,000 entrenched Japanese defenders. The kamikaze attacks not only drew blood on the Nevada. They sank or fatally damaged 33 warships and struck another 116 ships—from aircraft carriers to landing craft—killing about 5,000 sailors.

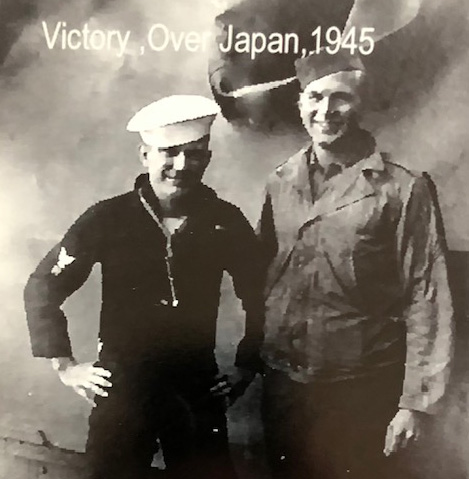

After the fighting on Okinawa finally ground to a halt, we expected even worse days ahead. Everyone feared that an amphibious invasion of the Home Islands of Japan was going to be a bloodbath many more times the intensity of either Iwo Jima or Okinawa. But then came word of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, followed by the stunning news that Japan had surrendered.

I remember clearly: The ship’s band played, we danced on deck, we laughed and cheered until our voices gave out. Some of us prayed in gratitude. Our war was over.

The Nevada was a proud ship. She was loved by the men who sailed her into battle.

Eighty years after the Nevada rose up from the mud at Pearl Harbor to confront the challenges of World War II, there are so few of us left. This is inevitable; our generation has passed. The world has turned and turned again, so many times, and the great sea battles that I and my shipmates endured have largely become lost to memory. But if there is one thing I pray that will never be forgotten, it is this: In a time of crisis and war, we young Americans stepped up, swore our oaths “to protect and defend,” and did our duty.