He was born a merchant’s son in 570 AD. Growing up in a world awash in decadence, deceit, and antiquated polytheism, he took to wandering the hills outside his hometown of Mecca, wandering and pondering, and received visitations from the angel Gabriel, who delivered to him the messages that became the wellspring of his theology.

With fire and sword and determination, he survived persecutions and gained a growing flock of followers. And by the time he died in 632, the religion that Mohammed had founded, Islam, had become a propulsive force, uniting the hitherto warring tribes of his homeland behind a common purpose and shared ideology.

Astride the world’s finest horses, the Muslim armies spilled forth from the Arabian Peninsula, and within a century’s time they would transport the Prophet’s message from Central Asia to North Africa to Spain. To the east, they conquered the Persian Empire. And to the west, they crashed up against the borders of that vestigial remnant of the glories of ancient Rome: the Byzantine Empire.

Islam’s war against this Eastern Roman bulwark would be a long one. At the epic Battle of the Yarmuk in 636, the surging Muslim forces annihilated the Byzantine Christian defenders and wrested Syria from the Roman orbit. The decisive victory handed the Muslims a whole new vista of possibilities. Having taken the Levant, they now were at the edge of the sea, beckoning with its promises of even more far-ranging conquests. They were desert warriors, not seafarers, but they would learn to be for the cause.

Here, along this coast of deeply rooted maritime traditions, land of Phoenician sea-rovers of old, the Arabs continued to expand the parameters of their conquests. Egypt fell in 641. And soon, a newly minted Arab fleet set out to raid, pillage, and conquer its way through the Byzantine-held islands of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Cyprus fell in 649, then Rhodes in 654, and the grim news reverberated to the Byzantine capital of Constantinople. Young Emperor Constans II was roused to react to this latest Islamic threat—a threat now seaborne. To quash this Muslim naval presence in its infancy, the emperor sent forth the mightiest fleet in the Mediterranean, 500 swift war galleys with crack crews of sailors and marines. In the face of this dominant force, the fledgling fleet of the Prophet was about to find out what it was made of.

The showdown came off southwest Turkey in 655. Not only was the Byzantine fleet superior in terms of naval skill, but it also outnumbered the vessels of the lubberly interlopers by more than two to one. While all comparisons augured in the Byzantines’ favor, their emperor had a weird, confusing dream on the eve of the battle, which was interpreted as an omen of pending defeat.

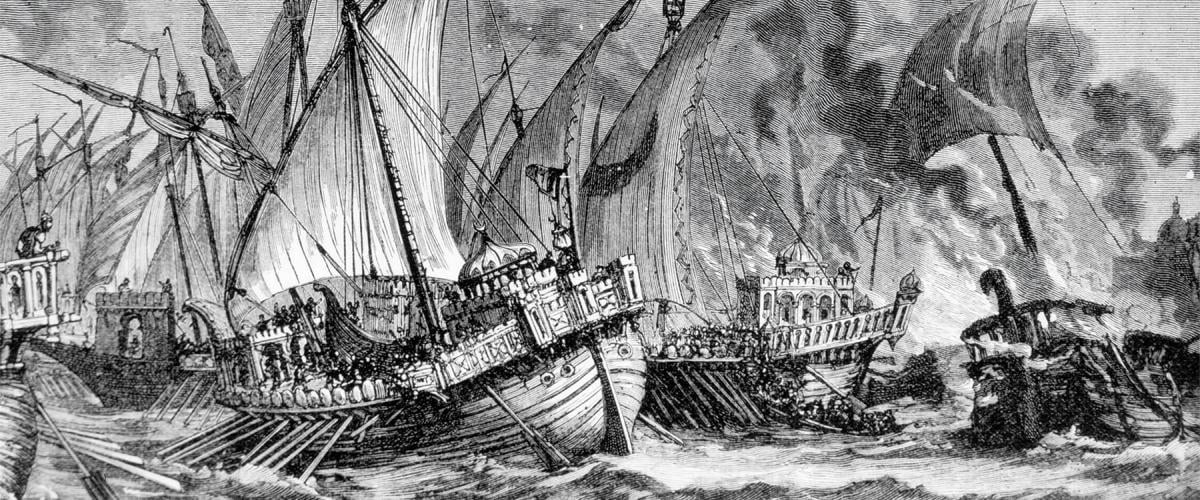

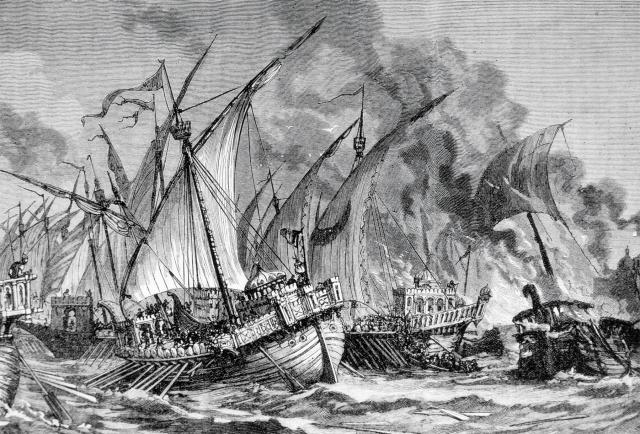

Nonetheless, Constans II engaged with seeming confidence, cavalierly sending his ships into the fray without ordering them into formation. As the vessels came within range, both fleets’ archers unleashed their deadly volleys, and the fight was on. The independently acting Byzantine galleys found themselves charging headlong toward an Arab fleet that had lashed its ships together, essentially creating a floating battle platform. So tightly amassed were the ships that they looked like a manmade forest—thus giving the battle its name: Dhāt al-Ṣawārī—the Battle of the Masts.

Along the decks, the Muslims formed in ranks, reciting the Koran in loud unison. The Byzantines closed and came storming over the side, charging into them, slashing. Across the forest of masts, it became a battle royale as both sides tangled ferociously. The Muslim historian al-Tabari recounted: “So they fought bitterly. At length God aided the Believers, and they made a great slaughter among the Byzantines, among whom only those who fled made it to safety.”

In the mayhem of close-quarters combat, such factors as superiority at naval maneuver had been rendered moot, and Byzantine confidence gave way to Byzantine carnage. The tables started to turn as Muslims began storming over the sides of Byzantine ships. “Although he had not made any preparations for the naval engagement, the Emperor ordered the Roman fleet into combat,” the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes ruefully observed. “When the two forces joined battle, the Romans were defeated, and the sea was mixed with Roman blood.”

Emperor Constans II exchanged clothes with some poor underling, escaped from his imperial ship, and, as Theophanes records, “He abandoned all his men and sailed away to Constantinople.”

After the Battle of the Masts, the Islamic naval threat would loom over the Mediterranean for centuries. A new sea power had made itself felt here. But in the immediate aftermath, the victors would fail to capitalize on their unexpected success—for in the very next year, the religion of Mohammed found itself ripped in two across a fault line between rival caliphate factions: the Shia and the Sunni. And that great schism that tore apart the faith in 656—right on the heels of its early victory at sea—continues to divide the Islamic world to this day.

Sources:

Salvatore Cosentino, “Constans II and the Byzantine Navy,” Byzantinische Zeitschrift 100, no. 2 (2007): 586–93.

Cecelia Holland, “Jihad by Sea,” MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 23, no. 1 (Autumn 2010), historynet.com/jihad-by-sea/.

R. Stephen Humphreys (transl.), The History of al-Tabari (Ta¯rīkh al-Rusul wa al-Mulu¯k, “History of the Prophets and Kings”), vol. 15, The Crisis of the Early Caliphate (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), 76–77.

Harry Turtledove (transl.), The Chronicle of Theophanes (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982), 45.