They were the pride of the Imperial German Navy’s elite East Asia Squadron—the sister ships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, armored cruisers with sharp, highly drilled crews, crack shots at gunnery and regular champs at the annual Kaiser’s Cup. But when the Great War erupted, the squadron’s home port of Tsingtao, China, was suddenly too hot a spot at which to remain, with Japan looming threateningly nearby. So Vice Admiral Graf Maximilan von Spee took his squadron and went mischief-making across the Pacific, all the way to the coast of South America.

There, off Coronel, Chile, Spee’s ships delivered a crushing, lopsided defeat to a Royal Navy squadron on 1 November 1914. The Germans suffered three wounded and lost not a single ship; the British had two armored cruisers shot out from under them and lost 1,660 men—including the squadron commander, Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock.

The Battle of Coronel was a bitter, humiliating blow to a Royal Navy that had grown used to victory; the British hadn’t lost a fleet engagement since the War of 1812, when the Americans on Lake Champlain had beaten them at the 1814 Battle of Plattsburgh. Britain thirsted for revenge—and realized the existential importance of shutting down the East Asia Squadron before more damage was done.

The Admiralty ordered out the big guns—HMS Invincible and Inflexible, a pair of heavy-hitting battle cruisers that would be backed by three armored cruisers, two light cruisers, and an armed merchant cruiser. Under the command of Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee in the Invincible, the ships were at the Falkland Islands and coaling up by the morning of 8 December—when word came that the German squadron had been sighted and was approaching.

As an officer rushed into Sturdee’s quarters with the alarming news, the admiral was just finishing shaving. Unruffled, he said, “Send the men to breakfast.” Sturdee’s coolness was in keeping with the character of an individual about whom it was said, “No man ever saw him rattled.” If there was to be a clash this day, his men would fight with full bellies. And besides, only two of his ships had completed coaling, and the 12-inch guns of the grounded pre-dreadnought HMS Canopus guarding the approaches would keep the Germans at bay until the squadron was ready to move.

The Germans, meanwhile, were realizing they’d stepped on a hornet’s nest. Rounding Cape Horn, Admiral Spee had decided to raid the Falklands before heading back to Germany—against the counsel of his officers. He would live just long enough to regret the decision. As the guns of the Canopus roared, the German squadron sheared off, any chance of a preemptive strike against the moored enemy now gone. When Sturdee’s squadron was finally ready to move and he ordered “General Chase,” a lusty cheer went up from the British crews.

The chase turned into a showdown once Spee realized his squadron simply didn’t have the requisite speed to get away. He ordered his light cruisers to continue fleeing; the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau would face down the enemy and buy the others time.

The British had every advantage of firepower and speed; they could both outgun and outrun the German ships. But the battle soon devolved into a confused affair, thanks to the bilious, enveloping clouds of black funnel smoke from the mighty British battle cruisers, a literal fog of war that destroyed visibility, rendering it damnably hard to spot the foe. Making matters worse was the fact that the British gunnery was astoundingly subpar; in hindsight, it would come clear that Sturdee’s gun crews had taken much longer to wipe out an inferior enemy than they should have.

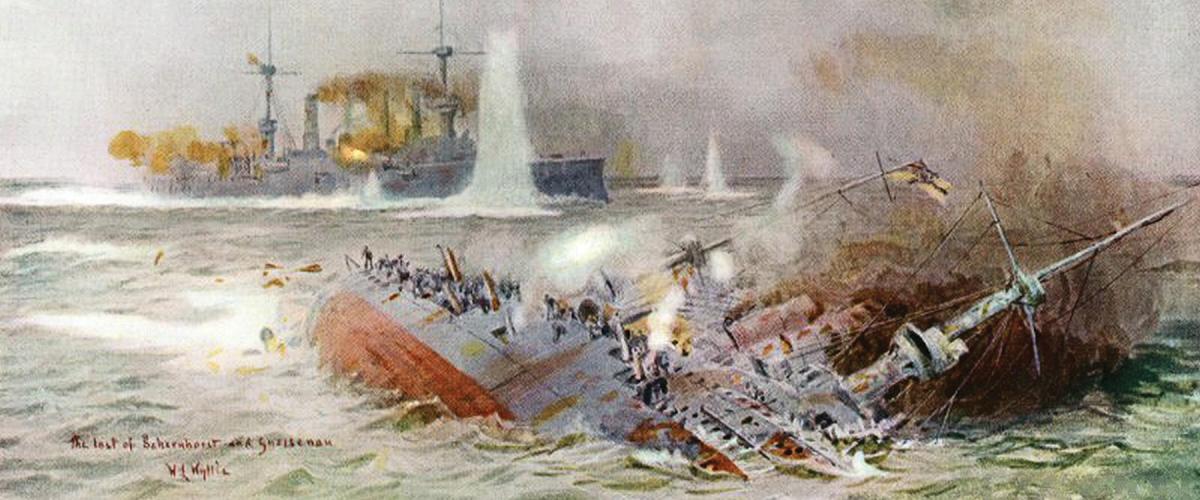

Spee’s gunners, on the other hand, demonstrated their famous accuracy throughout the fight, scoring plenty of hits, but ultimately to minimal effect on the thick-skinned armor of the behemoth British vessels. And as the back-and-forth maneuvering and pummeling continued, the Scharnhorst finally reached her sad end.

“The effect of [our] fire on the Scharnhorst became more and more apparent in consequence of smoke from fires and also escaping steam,” recounted Sturdee. “At times a shell would cause a large hole to appear in her side through which could be seen a dull red glow of flame. Notwithstanding the punishment she was receiving, her fire was wonderfully steady, and accurate, and the persistency of her salvoes was remarkable.”

The Scharnhorst went down fighting, all hands perishing with her—including Admiral Spee. And 29 years later—in another December, in another sea, in another world war—another German warship named Scharnhorst would meet her uncannily similar fate (see “When the Scharnhorst Took the Bait,” p. 36).

The Gneisenau was soon to follow. She was “listing heavily and sinking,” the Inflexible’s gunnery officer recalled. “She went over slowly and gave time for uninjured men to get on deck before the ship turned over on her beam ends. . . . There was no explosion, but steam and smoke continued to rise from the surface and hung in a thin cloud over the spot where she sank.”

After the main German combatants had been bested, the Battle of the Falkland Islands continued as the remaining ships of the dying East Asia squadron were hunted down and crushed; one final cruiser, though, would remain at large and not be cornered until March 1915.

Coronel had been avenged; the resounding victory in the South Atlantic boosted Allied morale at a time when there was little good news coming out of the war. But Germany’s East Asia Squadron had not gone softly into that good night. As Dr. T. B. Dixon, Royal Navy surgeon on board HMS Kent, observed, “The enemy fought splendidly, but were quite outclassed.”

Sources:

Geoffrey Bennett, Coronel and the Falklands (New York: Macmillan, 1962), 135–62.

Sir Julian S. Corbett, History of the Great War, Based on Official Documents: Naval Operations (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1920), vol. 1, 431–54.

T. B. Dixon, The Enemy Fought Splendidly: Being the 1914–1915 Diary of the Battle of the Falklands & Its Aftermath (Dorset, UK: Blandford Press, 1983), 26–31, 79–80.

Robert K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (New York: Random House, 2003), 257–86.