The American capture of the Mariana Islands in 1944 is often recognized as the decisive operation of the Pacific war. The operation delivered, in the words of historian Ian Toll, “the final and irreversible blows to the hopes of the Japanese imperial project.”1 Allied victory brought about the resignation of Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and his entire cabinet, placed American B-29 Superfortresses within range of Tokyo, and secured a forward U.S. naval base that promised an even greater threat to Japanese sea lanes.

The campaign also commenced the final sequence of battles that, collectively, drove the violence and ferocity of the Pacific war to new heights: Peleliu, Iwo Jima, Okinawa.2 Harrowing examples of mass civilian suicide at “Banzai Cliff” on Saipan’s northern edge suggested that Japanese civilians were likely to exhibit the same zealous loyalty, even to the point of death, as that displayed by their army counterparts.

These historical conclusions are sound, but the 15 June–9 July 1944 Battle of Saipan meant even more. At the tactical level, it marked a critical point of development in American fire control and coordination. In addressing the proximity of gunfire officers and coordination teams in battle, improving the communications infrastructure, and strengthening trust within the force, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps’ ability to adapt while at war positioned the Americans for the final, climactic battles of the conflict and helped lay a tactical foundation that endures in both national and international military doctrine today.

D-Day at Saipan

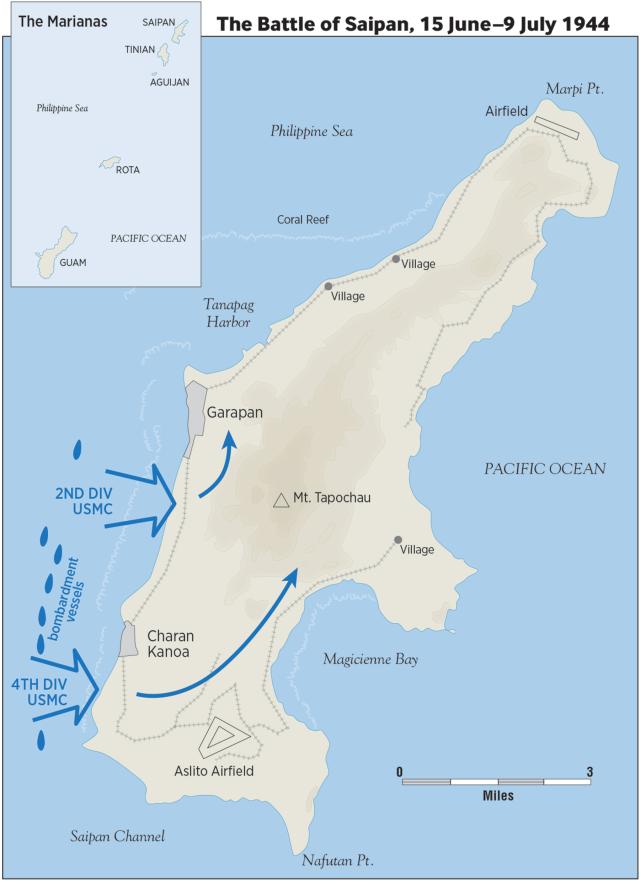

From the earliest of planning stages, Saipan demanded increased capacity from V Amphibious Corps. Unlike their previous attacks in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, the Marines would land two divisions abreast on a continuous beachhead. Saipan itself, at 14 square miles, dwarfed the meager 1.1 square miles of Betio and Roi-Namur Islands, the primary targets of the Corps’ earlier attacks in the Gilbert and Marshall Island chains. Operation Forager would require not only a multidivision landing, but also immediate cooperation with another service ashore. For the first time since Guadalcanal, V Corps would fight directly alongside an Army unit, the 27th Infantry Division.

V Amphibious Corps intended to match the scale of the Marianas challenge with overwhelming mass and a corresponding degree of firepower. On D-Day alone, 15 June, the Americans landed 20,000 troops, seven artillery battalions, and two tank companies. The divisions themselves carried far more destructive capacity than they had just one year earlier. At Saipan, the 2d and 4th Marine Divisions rated 243 portable flamethrowers per battalion, a tenfold increase over their 1943 quota.3

American mass came from the air as well. Just moments before the troops touched down, 60 F6F Hellcats, 51 SBD Dauntlesses, and 54 TBF Avengers attacked the beach from above. And there were plenty more planes at sea. All this while 13 battleships, nine cruisers, and 48 destroyers trolled the nearby waters, providing consistent gunfire support to the Marines on Saipan.4 Included in the fleet were the latest “fast” battleships of the Iowa class, with their 5- and 16-inch guns.5

The earliest reports on D-Day revealed just how difficult a target the Americans had met. Although the first three waves of Marines landed with few casualties, upon crossing the open beaches, the 2d and 4th Marine Divisions were forced to dig in and hold their positions in the face of registered Japanese artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire.6 The dogged resistance caused Marine Corps Lieutenant General Holland Smith to reassess his estimate of enemy strength on Saipan and activate all available reinforcements. First Lieutenant Frederic A. Stott, assigned to the 4th Marine Division’s reserve element, reported his surprise when, “moments” into the battle, his unit was ordered to their landing craft. Stott’s fellow Marines, similarly surprised by their early deployment, “crammed sandwiches into [their] pockets” as they descended to their landing craft.7

Hell on the Beach—and Hell from Above

The ensuing 24 hours were horrific for the Marines on the beach and their Japanese counterparts. Japanese commander General Yoshitsugu Saito launched a number of overnight and early morning counterattacks, hoping to dislodge the Americans’ hold on the beach. Smith’s Marines held firm, and the Japanese assaults weakened with each passing hour. By 17 June, relative attrition left the Americans with the momentum, and a joint force of the 4th Marine Division and 27th Infantry Division secured the island’s southern airfield the following day.8

By the second week of battle, the U.S. advance had decelerated, with General Saito’s detachment making determined use of the island’s rugged interior. Japanese snipers leveraged Saipan’s dense sugarcane and prepared defensive positions made for deadly interlocking machine-gun and mortar fire. Each ridge promised more danger and more casualties. To this dogged, enduring resistance, the Americans applied more firepower. As the infantrymen surged their use of flamethrowers and bazookas, and naval gunfire ships continued to provide ready weapons, four Army Air Forces P-47 squadrons landed on the recently captured airfield and established enduring air support for the soldiers and Marines. As had become habit in the Pacific, the complementary strength of air, land, and sea power enabled success ashore.9

Though Holland Smith would declare the island “secure” on 9 July, General Saito’s final order ensured that his detachment would fight—almost entirely—to its last breath. “Whether we attack or whether we stay where we are, there is only death,” he wrote. “I will advance with those who remain to deliver still another blow to the American devils. I will leave my bones on Saipan as a bulwark of the Pacific.”10

The United States’ victory at Saipan was the product of many ingredients. Relative surprise and tempo as well as the Americans’ extraordinary ability to place an abundance of men and matériel more than 5,800 miles from their own Pacific coast must be counted as impressive feats. Competing at the top of the list, however, is the literal mass of fires, and the network used to deliver those fires, throughout the campaign.

The Americans’ fire support efforts on Saipan were nothing short of staggering. The battleships USS Tennessee (BB-43) and Colorado (BB-45) each expended more than 1.2 million pounds of munitions.11 By battle’s end, naval gunfire expenditures reached 138,391 rounds totaling 17,082,292 pounds of ordnance—the rough equivalent of 97 Boeing 737s, fueled and loaded for takeoff. At the peak of on-call fire support, 40 naval gunfire liaison officers, 27 distinct shore fire-control parties, and 66 separate warships cooperated to deliver shells onto Japanese positions.12

Throughout the battle, U.S. ships and aircraft first requested and then begged for more shells, bombs, and ammunition. The acute shortages revealed just how indispensable sea- and air-based fire support had become to the American brand of triphibious (concurrent land, sea, and air) warfare. As early as the second day ashore at Saipan, naval commanders began to worry about severe ordnance shortages.

Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, Commander, Joint Expeditionary Force, himself requested that the ammunition ship USS Mazama (AE-9), laden with explosives, depart the Americans’ rear base at Eniwetok to help fill the void. In addition, Turner ordered all U.S. ships departing the Marianas theater to transfer any surplus 5-inch shells to the vessels remaining behind. He permitted off-going ships to retain just 60 rounds per gun for protection during their voyage. He similarly directed “all types of craft” stopping in Saipan waters to offload their excess ammunition. In all, U.S. warships offloaded 10,948 tons of naval shells and 2,233 tons of bombs and rockets in 195 impromptu ordnance transfers in the waters surrounding Saipan.13

Comms + Coordination = Unstoppable Force

In three particular areas, V Amphibious Corps made consequential tactical adjustments that allowed the Americans to effectively deliver such tremendous firepower at Saipan. Each adaptation facilitated the success of the assault and evidenced the Americans’ ability to address shortfalls and introduce iterative improvements across the campaigns of the Pacific war.

First, V Corps learned that proximity of personnel mattered in the effective coordination of firepower. Faced with the daunting fortress that was Saipan’s interior, as well as the enormous number of firing agencies involved in the three-division operation, V Corps Headquarters developed an informal working arrangement to physically co-locate its senior artillery, air, and naval gunfire representatives at the unit’s command post ashore. The move produced, in the words of Assistant Chief of Staff Colonel E. A. Craig, “the best functioning ever realized before.”14 Co-location provided critical advantages to the commanding general and his subordinate officers. The practice improved common awareness of completed, current, and pending fire missions; reinforced coordination between distinct arms; and ensured that unit commanders could engage the most effective weapon at the right moment in battle. By flattening communication channels, the ad hoc fire support center improved both the efficiency and effectiveness of U.S. firepower at Saipan. This embryo concept, applied and improved at Saipan, would go on to become the Marines’ formal Fire Support Coordination Center, first unveiled during the later assault on Iwo Jima, and surviving to this day as the central nerve center for fire support coordination.

The evolving infrastructure that facilitated such close coordination in the Marianas also was due to more efficient communications. In an effort to improve the reliability and responsiveness of communications, V Corps’ specialized Joint Assault Signal Companies (JASCOs) experimented with a number of additional frequencies on Saipan. Most notably, air, artillery, and naval gunfire liaison officers learned to switch their radios to a common frequency during simultaneous attacks, rather than remain on their primary (and necessarily saturated) general channels. It was the equivalent of placing a certified traffic guard at a busy downtown intersection, rather than relying on the intelligence, patience, and goodwill of individual drivers.

Simple as the radio solution may have seemed, it allowed for “highly effective” teamwork and near-immediate flexibility on the battlefield.15 On more than one occasion, the radio coordination allowed offshore fire support to come “as close as fifty yards” to the Marines. This high degree of precision delivered impressive barrages just in front of friendly American lines, and it played a critical role in repelling several Japanese counterattacks on Saipan. More importantly, it set a theoretical precedent for U.S. operations to come.16

‘The Enemy Holds Control’

Finally, relational trust within the task force played a decisive role in the Navy and Marine Corps’ ability to deliver such coordinated destruction. The JASCOs established a newfound reputation through their actions on Saipan and played an essential role in unifying action between the land, sea, and air forces. In particular, the specialized companies’ unique training background—built around an appreciation for triphibious operations—bred confidence in the frontline Marines and the sailors firing at sea.

As one task group commander, Rear Admiral Walden Ainsworth, wrote, the close cooperation of the task force allowed “our aviators to step up their dive bombing and strafing attacks to a furious intensity from low [altitude] levels.” In a “beautifully coordinated” action, he noted, “naval gunfire of all calibers pounded enemy objectives unceasingly and swept the landing beaches continuously, interrupted only by our perfectly timed air strikes.”17 This improved coordination allowed for the efficient processing of fire requests as well as effective and timely prioritization of targets. “The value and necessity of the [JASCOs],” wrote a U.S. signal officer, “cannot be over emphasized.”18

If the words of American participants themselves might appear too biased, the objectivity and authenticity of Japanese accounts can hardly be questioned. Following the battle, dozens of testimonies from enemy prisoners of war as well as several captured Japanese reports revealed a common verdict: Air and naval firepower was the decisive ingredient in the U.S. victory. Just days into the struggle for Saipan, one Japanese document acknowledged the Americans’ advantage and the defenders’ own consequent dilemma: “The fight on Saipan as things stand now is progressing one-sidedly, since, along with tremendous power of his barrages, the enemy holds control of sea and air. . . . Moreover, we are menaced by brazenly low-flying planes, and the enemy blasts at us from all sides with fierce naval and artillery crossfire.” A separate mid-battle summary emphasized the same reality: “the enemy is gradually advancing under cover of fierce naval gunfire and bombing and strafing.”19

A Triumph Overshadowed

Unfortunately, history has clouded and underemphasized the significance of the battle for Saipan. Historians themselves have proven complicit. James Bradford’s masterful textbook America, Sea Power, and the World—the curricular backbone of the U.S. Naval Academy’s naval history course—covers the battle in just three sentences.20 The attack is all too often overshadowed by the Allies’ dramatic and much more anticipated landing at Normandy that very same month, in early June 1944. (See “The Invasion Fleet that Liberated Europe,” pp. 28–35.) For its part, the unfortunate controversy over Marine General Holland Smith’s relief of Army Major General Ralph Smith prompted far too many pages of relatively petty debate, further concealing the importance and achievement of the U.S. victory.

Triumph at Saipan was fueled by American industry and logistics, enabled by U.S. air and naval supremacy, and delivered by the effective wartime adaptation of triphibious forces, namely, their ability to control and coordinate devastating air, naval, and ground-based fires. In the words of historian Joseph Alexander, the Americans’ attack at Saipan was a “storm landing,” what Alexander defined as “the audacious concentration of overwhelming force at the point of attack.”21 What previous historians have not fully accounted for is the flexible and evolutionary system of fire control and coordination necessary to concentrate that overwhelming force—and to deliver Allied victory in the Central Pacific.

1. Ian W. Toll, The Conquering Tide: War in the Pacific Islands, 1942–1944 (New York: W. W. Norton, 2016), 513.

2. Harold J. Goldberg, D-Day in the Pacific: The Battle of Saipan (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2007), 1–3.

3. Sharon Tosi Lacey, Pacific Blitzkrieg: World War II in the Central Pacific (Denton, TX: University of North Texas Press, 2013), 132; Toll, Conquering Tide, 466.

4. Support Aircraft Commander, CTF-51, ch. 2, “Air Support,” in “Amphibious Operations—Invasion of the Marianas, 30 December 1944,” World War II Battle Reports and Analyses, Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD (hereafter SC&A, USNA), 2-1.

5. It is worth noting that a single projectile from that 16-inch naval gun weighed the same as a standard passenger car.

6. “Capture of Saipan” in “Amphibious Operations—Invasion of the Marianas, 30 December 1944,” World War II Battle Reports and Analyses, SC&A, USNA, 1-3–1-5.

7. Frederic A. Stott, Saipan Under Fire (Andover, MA: privately printed, 1945), 3.

8. Toll, Conquering Tide, 468–69.

9. “Capture of Saipan,” 1-5; “Chronology of Events Affecting Supporting Fires,” in Secret Information Bulletin No. 20: “Battle Experience Supporting Operations for the Capture of the Marianas Islands (Saipan Guam Tinian) June–August 1944, 21 December 1944,” World War II Battle Reports and Analyses, SC&A, USNA, 74-12.

10. “Memorandum 15-44: Lieutenant General Saito’s Last Message to Japanese Officers and Men Defending Saipan,” 12 July 1944, Mariana Island Collection (COLL/3666), U.S. Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA (hereafter COLL/3666, MCHD), 1.

11. “Naval Gunfire Support in the Marianas Operation,” 17 December 1944, COLL/3666, MCHD, 1–3.

12. “Call Fires,” in Secret Information Bulletin No. 20, 74-50.

13. “Ammunition,” in Secret Information Bulletin No. 20, 74-44–74-45.

14. E. A. Craig, “Coordination of Air, Artillery, and Naval Gunfire,” 1 October 1944, Historical Amphibious Files, COLL/3634, MCHD, 1.

15. Charles S. Corben, “Naval Gunfire Report,” enc. in Headquarters Northern Troops and Landing Force: Marianas Phase I (Saipan), 10 August 1944, COLL/3666, MCHD, 7.

16. Corben, “Naval Gunfire Report,” 7; Samuel Taxis, interview by Benis M. Frank, 27 August 1981, Marine Corps Oral History Collection, Archives Branch, MCHD.

17. RADM Walden Ainsworth, “Commander Task Group 53.5 Comments,” enc. in Secret Information Bulletin No. 20, 74-48–74-49.

18. Signal Officer, “Signal Communications,” enc. in “Signal Officer’s Report: Phase 1 (SAIPAN),” 1944, COLL/3666, MCHD, 32.

19. Captured enemy reports quoted in “Naval Gunfire Report,” enc. in “Northern Troops and Landing Force: Report of Marianas Operation Phase I (Saipan), 10 August 1944, COLL/3666, MCHD, 20-21.

20. James C. Bradford, America, Sea Power, and the World (Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell, 2016), 232.

21. Joseph H. Alexander, Storm Landings: Epic Amphibious Battles in the Central Pacific (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 63.