In the Pacific Theater of World War II, the United States—wielding a trident of air, sea, and amphibious forces of unprecedented strength and sophistication—brought the expansionist Japanese Empire to utter defeat and unconditional surrender. One legacy of that conflict is the large number of island bases and airfields that still exist, in one form or another, across that vast oceanic battlefield.

Before 1941 such bases, whether built by Japan or the United States, were few and far between; however, the requirements for land-based air power and fleet replenishment for both defensive and offensive operations saw a large number of bases built where none previously existed. They provided the “stepping stones” that enabled U.S. forces to advance west through the Central Pacific to the Japanese Home Islands in less than two years.

These stepping stones, like the roads of ancient Rome, also provide a means for both defending and invading forces to move in either direction.

In early 1944, this strategic dilemma was identified by Admiral Chester W. Nimitz as a potential threat for the postwar security of the United States and its allies. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean Area, foresaw the possibility of a new aggressor from the West Pacific at some future time using these same bases to assert sea dominance in the Pacific. Navy planners would do well to consider his prescient analysis as they plan for future conflict in the Indo-Pacific.

Advanced Bases in Theory and Practice

In the early 20th century, the U.S. Navy’s plan for a war with Japan, known as War Plan Orange, envisioned the necessity of seizing islands in the Central Pacific as bases for its naval forces advancing west to engage the Imperial Japanese Navy.1 The issue became more complicated in the aftermath of World War I, when Japan was granted a League of Nations mandate over the former German colonies in the Caroline and Marshall Islands—the very island groups that were deemed crucial for establishment of advanced bases from which the U.S Pacific Fleet could operate.2

U.S. Marine Corps Major Earl H. “Pete” Ellis made the first major study of how these islands would be seized in his seminal Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia. Ellis identified the many issues an invading force would face in seizing the coral atolls and volcanic islands of the Central Pacific, stressing the need for rapidity of action and the use of well-trained amphibious forces. His study laid out a preliminary plan for landing operations, including the need for offshore naval gunfire support, the use of aircraft for bombing and strafing, and the need for well-established lines of communication—the very elements that would prove vital to the success of the U.S. Navy’s amphibious operations in the Pacific war.3

In 1938 the naval services adopted Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy, FTP-167, a work developed from Ellis’ concepts by the Marine Corps College. This manual became the basis for all amphibious operations in the Pacific war and emphasized two factors critical to the success of such operations: securing and maintaining local sea control and obtaining air superiority with shore-based aircraft. The latter was now deemed essential. The seizure of islands for the use of shore-based aircraft on “unsinkable aircraft carriers” was recognized as one of the primary objectives of landing operations:

108.(b) Due to the importance of aircraft in fleet engagements . . . territory which otherwise might have no strategical or tactical value assumes an important role as possible air bases.4

The Japanese also valued advanced bases, and within days of their attack on Pearl Harbor they moved amphibious forces out of their bases in the Mandates and seized a number of lightly defended British and Commonwealth territories, first in the Gilbert Islands and later in the Bismarck Archipelago and the northern Solomon Islands. However, further Japanese advances in the Pacific were halted by the Battle of the Coral Sea on 7–8 May 1942, followed a month later by the disastrous Japanese loss at Midway. These successes allowed Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), to step up his “defensive-offensive” campaign for the next 18 months, using the available Allied forces to secure the sea lines of communication with Australasia and to conduct attritional operations to whittle away Japan’s air and sea power.5

Major offensive operations would have to wait for America’s industrial might to provide King and Nimitz with the new fast battleships, aircraft carriers, transports, landing craft, and, above all, superior aircraft they would need to begin the long-awaited drive west. (As well as CNO, King was the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet, and a member of the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff. They had agreed to a “Germany First” policy, and it was not until 1943 with the German defeats at Stalingrad and Tunisia that they felt it advisable to shift resources to the Pacific Theater.)

The Imperial Japanese Navy had long been aware of the U.S. Navy’s strategy to use the Mandate Islands as stepping stones to the Japanese Home Islands, and devised its own “Doctrine of Decisive Battle” to defeat such a move.6 Through the strategy of “interceptive operations,” the Imperial air and naval forces located in the Mandates would attrit the U.S. Pacific Fleet as it moved west until the Combined Fleet could meet it on favorable terms and defeat it in a Mahanian-style decisive battle.7 Interlocking interception zones would be established from the Aleutians in the north, across the Central Pacific, to the Solomon Islands in the south, with strong advanced bases located within mutual air-support distance from each other, typically 300 miles. The Combined Fleet would be held in readiness to attack when called on, but it was not to be risked unless positive results were guaranteed.

This system of overlapping zones of interception meant that Japanese air forces, surface ships, and submarines could be quickly converged on the American transports and their supporting naval forces. Successful landing operations therefore would call for speed and efficiency to minimize the time such forces would be exposed to counterattack. Seizing coral islands and atolls in the middle of the Japanese defensive perimeter would be fraught with danger. However, with dozens of islands to defend, the Japanese defenses were necessarily spread thin, and the small size and flat terrain of the coral atolls were factors limiting the size and density of the defenses.

Operation Galvanic Sets the Pattern

The long-awaited drive west began on 20 November 1943 when Nimitz’s Fifth Fleet, under the command of Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, struck back in the Gilbert Islands, at Tarawa and Makin Atolls, in an operation codenamed Galvanic. (At the time, Spruance’s force was known as the Central Pacific Force, but it would be rechristened the Fifth Fleet after the successful capture of Eniwetok Atoll in February 1944.) The assault on Betio Island in the Tarawa Atoll was the first amphibious landing conducted against a heavily defended shore and resulted in high casualties, with more than 1,000 Marines killed in the four-day operation (see “Blood and Coral,” December 2023, pp. 20–27). Nevertheless, Operation Galvanic was highly successful and gave the Allies a much-needed toehold inside the Japanese defensive perimeter.

After the bloody experience of Tarawa, Spruance and his staff built on the hard lessons learned and organized a brilliant campaign to seize control of the Marshall Islands using the new positions in the Gilberts as the launching pad. The ensuing capture of the Kwajalein and Eniwetok Atolls in January and February 1944 was described as “probably the most perfect operation of its kind in the war.”8 It caught the Japanese unprepared, and the detailed planning by Spruance and his staff, and the near-flawless execution by the fleet, resulted in a fraction of the casualties suffered previously.

These operations then set the pattern for the future: meticulous planning and rehearsals; striking with speed and secrecy to obtain tactical surprise; days of intense naval and aerial bombardment immediately followed by an amphibious assault using tracked landing vehicles; rapid assault by forces highly trained in the use of high explosives and flamethrowers, outnumbering the defenders by a ratio of 4 to 1 or greater; and comprehensive logistical support for both the amphibious and the naval support forces. Construction Battalions (Seabees) would follow the first assault waves and begin rebuilding damaged airfields, putting them back in operation even before the island was declared secure.

Escort carriers and battleships would provide on-call naval gun and close-air support while fast-carrier task forces suppressed air attack from adjoining Japanese bases and provided screening from any counterattack by the Japanese Combined Fleet. Spruance’s overall strategy was simple: With speed and secrecy, isolate the objective from reinforcement and resupply and attack it with overwhelming force, while holding any attempt at counterattack by air or sea at arm’s length with the fast-carrier task forces.

Nimitz Looks to the Future

Following major operations Admiral King’s headquarters in Washington reviewed the after-action reports made by commanders at every level and extracted “lessons learned” and recommendations for future operations. These were then collated and disseminated back to the fleet as Secret Information Bulletins.

In Bulletin No. 17, Battle Experience—Supporting Operations for the Occupation of the Marshall Islands Including the Westernmost Atoll, Eniwetok, February, 1944, Nimitz considered the successive and rapid island conquests made under his command as proof of the failure of Japan’s strategy of dependence on fixed bases. In a section titled “Mobile Forces Versus Bases,” he wrote:

Their broad strategy seems to have been based on the belief that by moving quickly and seizing and developing an interlocking system of bases . . . their position would then be impregnable. This strength in bases was expected to off-set any superiority in mobile forces which we might conceivably succeed in creating . . . The weakness of this reliance on bases . . . lay in the fact that any base can be neutralized or captured if sufficient force is brought against it, and if it is cut off from supply, support, and reinforcement . . . it would be possible to isolate and dominate a wide area where the enemy’s strength lay in the number of his bases rather than in the size and effectiveness of his mobile forces . . . and that troops, trained for amphibious warfare and made mobile by air and surface support and transportation, could then assault and occupy key points within this area, from which the remainder could then be throttled into impotence or more readily captured.9

Nimitz noted that the Japanese had established so many bases that they were unable to allocate sufficient troops and aircraft to the local defense of each, and that “Japanese mobile air and surface strength finally could not cope with our own and prevent us from attacking wherever we willed with forces greatly superior to the local defense.” Nimitz praised the ability of the Seabees to build airfields with great speed and “in places where nobody believed one could be built at all . . . at leveling off mountains and filling up valleys we already surpassed the world; such jobs were mere routine to American industry; and our peace-time techniques were readily adaptable to war-time needs.”

Never doubting the eventual outcome of the war, Nimitz began to look to the future. Not knowing what conditions might be forced on Japan after its surrender, he thought that “during the next twenty or thirty years,” a resurgence of Japanese military power was entirely possible, and that the United States and its allies once again would be found complacent and unprepared to defend the advanced bases they had acquired.

Nimitz wrote:

But should a future situation arise in which the large number of airfields throughout the Pacific may be nominally ours or our Allies’, but are defended poorly or not at all, it will not be then a question of who can build fastest, but of who can seize most of what is already built. In this there is no question but that the advantage will lie with an enemy who has been preparing for it secretly, who is willing to strike treacherously, who has become equal or superior to us in mobile forces of all kinds, and who has learned well from us how to utilize these forces in the neutralization and reduction of bases over wide areas. To prevent such a condition from ever existing must be our concern in the future.10

Nimitz thought that, while the built infrastructure of an air base—hangars, barracks, fuel storage tanks, and the like—could be easily destroyed, it was the runways that would prove particularly invulnerable to destruction. After all, even after severe aerial and naval bombardment, the Seabees had been able to rebuild and enlarge them quickly, and the Japanese themselves were adept at restoring runways to operational status in short order. (For this reason, during the assault on Roi-Namur in the Kwajalein Atoll, Spruance ordered that naval bombardment continue through the night to prevent the Japanese from making repairs to the runways there.) One of the most difficult jobs in constructing runways is the task of clearing, leveling, and compacting the base of the hardstand, and once that is done, they are hard to eradicate.

Proof of Nimitz’s concern can be seen in the partial list of airfields still in existence on the legacy bases, as shown in the accompanying table. Even badly deteriorated airfields could be quickly brought back to life sufficient for field operations. In addition to the airfields, the Seabees and the Navy Civil Engineering Corps also built extensive harbor facilities and breakwalls, cleared and deepened channels into lagoons, and created fleet anchorages where none had existed before.

These facilities could be extremely useful for future operations by either a defender or an invader.

Lessons from the Pacific War

Nimitz was justified in worrying about the future status of the bases that were created, and still exist in one form or another, throughout the Pacific. He would be pleased that Japan is no longer a threat to world peace but is instead a valued ally; equally, he might be surprised to see that China has risen to become a peer adversary.

Today, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China is looking at the Pacific war for lessons in offensive joint operations. Toshi Yoshihara, looking at current Chinese professional military literature, finds that the PLA is actively looking at the conduct of the Pacific war for lessons it might apply in the future.11 The PLA seeks to emulate the role played by the U.S. Navy in seizing command of the sea and air from Japan from a position of strength. This is in sharp contrast with some American historical analyses that see China in the role of Japan, fighting primarily defensive battles from a position of relative weakness.

Looking for lessons in the Battles of Midway, Guadalcanal, and Okinawa, Chinese historians and analysts time and again have returned to the importance of seizing and maintaining air control in the area of the objective, with “close cooperation between air, sea, and ground forces in conjunction with ample material support backed by a massive defense industrial base” as the primary factors that led to the success of the U.S. military in the Pacific war.12 While generally dismissive of Japan’s war strategy and critical of its commanders’ repeated failure to follow through on tactical victories to gain strategic advantage, they share a common doctrinal preference for surprise and first strike.13 These historians and analysts foresee the PLA conducting similar joint offensive campaigns to seize island terrain from a position of parity with the United States and its allies.

Beyond the First Island Chain

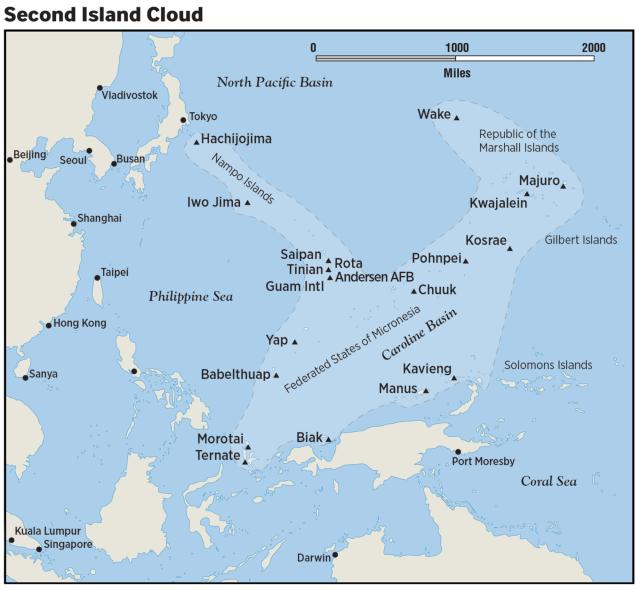

While main focus of China’s aspirations in the West Pacific is Taiwan, Beijing also recognizes the strategic importance of the Second Island Chain and beyond. The Second Island Chain may be better thought of as the Second Island Cloud, being a continuum of island groups rather than a single barrier.14 The Second Island Cloud stretches from the Bonin Islands and Iwo Jima in the north, south through the Marianas, west to the Marshalls, and then southwest through the Carolines to Palau and the islands off the north coast of New Guinea, encompassing most of the legacy bases of the Pacific war.

The large number of islands here provides an opportunity for the wide disbursement of the U.S. Marine Corps’ Expeditionary Advanced Base (EAB) forces, enabling them to conduct sea denial over a vast area. As mentioned, most of these islands have an airport that can provide a useful base of operations for Marine MV-22 transports and F-35B fighters. Many atolls in the Second Cloud, such as Ulithi and Majuro, have large anchorages protected from subsurface attack, which could be havens for repair and resupply just as they were during the Pacific war. Provided that the EABs and their supporting forces can remain mobile, the Second Island Cloud provides ample bases from which to support both stand-in and stand-off forces operating in the West Pacific.15

The Second Island Cloud is also well placed to conduct a distant blockade of China’s maritime trade by precluding movement into the North Pacific and the Arctic, as well as to Central and South America, all major sources of food and natural resources for China and areas of concern to U.S. planners.16

The PLA surely values the legacy bases for much the same reasons: They provide a ready-made infrastructure to locate forces to support an advance east to secure area denial and sea control, to open their preferred sea lanes, and to cut the sea communications between the North American and Australasian allies. The PLA also is well aware of the U.S. Marine Corps’ pivot to joint fleet operations and the EABO (Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations) concept and likely will seek to emulate it.17 Chinese strategists know that the replenishment and reinforcement of forward-based U.S. and allied forces in the First Island Chain, including the EABs, will have to move through the Second Island Cloud.

In order to establish a presence in the Second Island Cloud, the Chinese have started to make inroads with the governments of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), which have sovereignty over the Caroline Basin. The FSM have been the subject of much Chinese investment in infrastructure and are one of the few governmental entities in the region to recognize mainland China’s claim to sovereignty over Taiwan. FSM President David Panuelo recently expressed an interest in his nation becoming part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.18 The Republic of Kiribati in the Gilbert Islands recently dropped recognition of Taiwan in exchange for loans and development funding, opening the way for Chinese access beyond the Second Island Cloud—in the very place where the bloody Battle of Tarawa was fought.19

China values Micronesia as an important fishery and as a potential source of rare earth minerals and metals.20 Chinese activities in the form of development loans and investment within Micronesia, while legitimate on their face, create dependency. Building roads and enlarging airports provides Micronesia with much-needed infrastructure, while providing the builders with valuable intelligence about these island groups.

The bulk of Chinese investment in Micronesia has been on Chuuk, formerly known as Truk, once considered to be the “Gibraltar of the Pacific.”21 Information about the islands of the old Japanese Mandates was unavailable to the Allies in 1943, and costly operations such as the Tarawa campaign were required to bring reconnaissance aircraft within range to obtain it. China reaps both good will and an intelligence bonanza at a low cost by comparison.

Islands of Renewed Vital Importance

U.S. and allied forces today face the same dilemma as once did the Japanese: which bases should be defended and how to allocate scarce forces across a vast area. If the PLA can succeed in establishing a numerically superior and well-equipped force beyond the First Island Chain, the Chinese may find themselves in the same position as Nimitz did in 1944:

. . . the superiority of our mobile forces, air and surface . . . permitted us to effect the occupation wholly unopposed from outside, to bring crushing superiority in assault troops and supporting fire against the isolated defenders, and ultimately to dominate many enemy bases from the comparatively few that we had captured.22

With the ability to choose which bases to seize and use “crushing superiority” to overwhelm the defenders, other bases, perhaps more strongly defended, can be bypassed and left to “wither on the vine” by the denial of reinforcement and resupply. Unable to resupply by sea or air, the Japanese resorted to using submarines to trickle supplies into their beleaguered garrisons; suffice to say the U.S. Navy will not want to place multibillion-dollar platforms at risk conducting similar missions.

The legacy bases of the Central Pacific provide both an opportunity and a potential threat to U.S. and allied plans for a confrontation with the PLA. The sheer number of islands and the vast distances involved make occupying and defending these legacy bases a daunting challenge.

Nimitz noted that “our strategists of the future . . . will undoubtedly wish it were possible to open the sea-valves on many a Pacific island and scuttle it, thus streamlining our holdings down to the minimum that we need for operations and the maximum that we can properly defend.”23

Nimitz’s future is now. As no one has yet devised a means to scuttle an “unsinkable aircraft carrier,” it will behoove present-day strategists to pay close attention to these legacy bases—the double-edged sword of the Pacific.

1. Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 36.

2. Miller, War Plan Orange, 116.

3. Maj Earl H. Ellis, USMC, Advanced Base Operations in Micronesia, www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/USMC/ref/AdvBaseOps/Advanced-4.html.

4. Navy Department, Washington, DC, Landing Operations Doctrine, United States Navy, 1938, FTP-167, Rev.3, 1 August 1943, ch.1, para. 110, 111, https://archive.org/details/landingoperation00unit_0.

5. Ian W. Toll, Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941–1942 (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2012), 84.

6. David C. Evans and Mark R. Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press,1997), 282–83.

7. John Prados, Combined Fleet Decoded (New York: Random House, 1995), 59–61.

8. VADM E. P. Forrestel, USN (Ret.), Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, USN, A Study in Command (Washington, DC: U.S. Navy History Department/Government Printing Office, 1966), 109.

9. Commander-in-Chief, U.S Fleet, Secret Information Bulletin No. 17, Battle Experience—Supporting Operations for the Occupation of the Marshall Islands Including the Westernmost Atoll, Eniwetok, February, 1944, 16 October 1944, 70–126 (hereinafter Nimitz, Battle Experience, Marshalls), Archives, Digital Collections, World War II, Battle Reports and Analyses, Nimitz Library, U.S. Naval Academy.

10. Nimitz, Battle Experience, Marshalls, 70–128.

11. Toshi Yoshihara, Chinese Lessons from the Pacific War: Implications for PLA Warfighting (Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 2023), 19.

12. Yoshihara, Chinese Lessons from the Pacific War, 52.

13. Yoshihara, 91.

14. Andrew Rhodes, “The Second Island Cloud: A Deeper and Broader Concept for American Presence in the Pacific Islands,” Joint Force Quarterly 95 (4th Quarter 2019): 46–53.

15. James Lacey, “The ‘Dumbest Concept Ever’ Might Just Win Wars,” War on the Rocks, 29 July 2019, warontherocks.com/2019/07/the-dumbest-concept-ever-just-might-win-wars/.

16. John Grady, “Chinese Investment Near Panama Canal, Strait of Magellan Major Concern for U.S. Southern Command,” USNI News, 24 March 2022, news.usni.org/2022/03/24/chinese-investment-near-panama-canal-strait-of-magellan-major-concern-for-u-s-southern-command.

17. Conor M. Kennedy and Col Scott E. Stephan, USMC, “The PLA is Contemplating the Meaning of Force Design,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 149, no. 4 (April 2023): 29–33.

18. Pranay Varada, “Micronesia: The Next US-China Battleground,” Harvard International Review, 6 December 2021, hir.harvard.edu/micronesia-the-next-us-china-battleground-2/.

19. Bruce Jones, “Temperatures Rising: The Struggle for Bases and Access in the Pacific Island,” Brookings Foreign Policy Brief, February 2023, 5, www.brookings.edu/research/temperatures-rising-the-struggle-for-bases-and-access-in-the-pacific-islands/.

20. Denghua Zhang and Gonzaga Puas, “China Meets its Limits in Micronesia,” East Asia Forum, 8 April 2020, www.eastasiaforum.org/2020/04/08/china-meets-its-limits-in-micronesia/.

21. Varada, “Micronesia.”

22. Nimitz, Battle Experience, Marshalls, 70–127.

23. Nimitz, 70–128.