Practical flight was less than eight years old when the U.S. Navy made its first tentative commitment to put sailors aloft in heavier-than-air craft. On 4 March 1911, Congress passed the 1911–12 Naval Appropriations Act, which allocated $25,000 to the Navy “for experimental work in the development of aviation for Naval purposes.” The way forward for Navy Air was unclear, even for the few visionaries who pushed for the investment. Having been appointed on 26 September 1910 to represent the Navy Department on aeronautical matters, Captain Washington Irving Chambers had argued for the appropriation and was named to oversee the use of the money. His official title—Assistant to the Aid for Material—camouflaged his specific duties.

Before Chambers had requested the funds, he arranged for naval demonstrations of aircraft to pique Navy and congressional interest. He orchestrated two well-known flights of Eugene B. Ely: landing on board the cruiser USS Birmingham (Scout Cruiser No. 2) on 14 November 1910, and taking off from the quarterdeck of the Pennsylvania (Armored Cruiser No. 4) on 18 January 1911.

While Navy Secretary George Meyer was impressed by Ely’s flights, he was unconvinced of a role for aircraft in the service. He wrote to Glenn H. Curtiss, who built Ely’s airplane: “When you show me that it is feasible for an aeroplane to alight on the water alongside a battleship and be hoisted aboard without any false deck to receive it, I shall believe the airship of practical benefit to the Navy.”

Curtiss took up the challenge. Although a “hydroaeroplane” had been flown in France and Curtiss had experimented with floats on an earlier aircraft, no such craft was available in the United States. By mid-February 1911, Curtiss taxied his first practical hydroaeroplane to the Pennsylvania, anchored in San Diego Bay, and the crew hoisted it on board using a boat crane. After a short speech, the plane was lowered over the side, and Curtiss took off for his camp on North Island, having answered the Navy Secretary’s call.

Later that month, Chambers persuaded Curtiss to convert the new design into an amphibian by providing it with wheeled landing gear. On 26 February, Curtiss flew from water to land to water, proving the concept. He named the aircraft Triad to denote its air, land, and water operations.

Meanwhile, the Navy accepted Curtiss’ offer to train a Navy aviator at his own expense, and on 2 January 1911, submariner Lieutenant Theodore G. Ellyson reported to Curtiss for training at North Island.

All this was done before the Navy had any money for aviation.

When funds were allocated, Chambers ordered three aircraft on 8 May 1911—the date the service considers as the official birth of U.S. Navy aviation. Two were from Curtiss—a Triad-type hydroaeroplane and a landplane for training—as well as one Wright Brothers aircraft fitted with pontoons for water operations.

The two Curtiss aircraft, built in Hammondsport, New York, at the southern end of Keuka Lake, were the first accepted by the Navy and designated A-1 (the Triad) and A-2. The Wright biplane, designated B-1, was delivered last and without the required floats for water capability. All three were very much works in progress throughout their entire service lives. The field of aviation, in general, was completely experimental, and the Navy aircraft melded new technology with an ancient tradition-bound service.

A-1, a pusher-type biplane, was ready for testing at Hammondsport by June 1911. It was powered by a 50-horsepower Curtiss engine until 7 July, when a 75-horsepower V-8 engine was installed. The aircraft cost the Navy $5,500, approximately $178,125 in 2024 dollars.

A-1 first flew on 1 July with Curtiss at the controls; the five-minute flight gauged balance and stability. Another five-minute flight followed with Ellyson on board to determine the plane’s characteristics with two people. Ellyson followed with two solo flights. The next day, he made two more flights, which qualified him for Aero Club of America License No. 28, Military Aviator’s Certificate No. 26, and Naval Aviator’s Certificate No. 1.

The next day, Ellyson attempted to fly Chambers about 20 miles to Penn Yan at the northeast end of Keuka Lake. A-1 would not fly, so Ellyson taxied Chambers there. He then flew back to Hammondsport, where he was forced into making the Navy’s first night landing.

The two Curtiss aircraft were scheduled for delivery to the Navy in late July at Greenbury Point across the Severn River from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Ellyson requested a delay for more trials and testing. Because the new aerodrome was not scheduled for completion until September, the Navy readily agreed.

On 7 July, Curtiss made three test flights in A-1 with the new engine, including one with Ellyson. The pontoon’s position was shifted forward about two inches to accommodate the new engine’s weight, and a larger fuel tank was added. Three days later, Curtiss made A-1’s 24th flight. He flew from land, retracted the landing gear in flight, and landed on the lake. On the 12th, the pontoon and floats were removed, and A-1 was converted to a land-plane configuration.

Over the summer, Ellyson logged more than 50 flights, totaling more than 11 hours. On 21 August, while flying with Lieutenant (junior grade) John H. Towers over the lake, the engine quit. The plane crashed and was badly damaged, but the crew escaped unharmed. A-1 was repaired within a week.

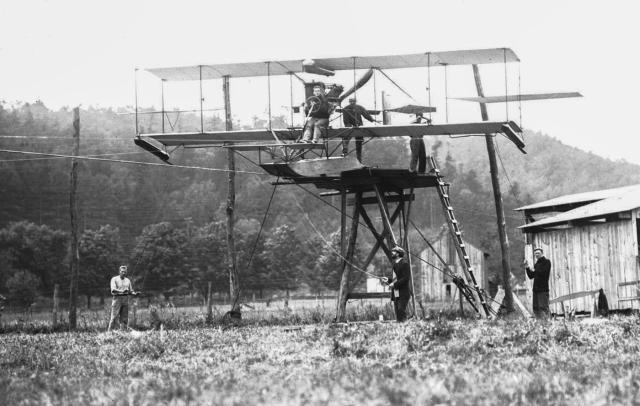

In early September, Ellyson and Curtiss stretched a cable from a platform to the lake’s edge to test the feasibility of a shipboard launching device that would require no deck modification. Curtiss aimed to slide an aircraft down the inclined cable to reach flying speed. On 7 September, Ellyson attempted a launch and reported, “Everything happened so quickly and went so smoothly that I hardly knew what happened.” He had traveled barely 150 feet on the 250-foot-long cable.

While Curtiss touted this as proof of concept, Chambers was not so certain. He believed the method impractical from the deck of a rolling, pitching ship. He envisioned a catapult mounted on the stern, where air currents were calmer and a faltering aircraft would not be run over by the launching ship.

After 69 A-1 flights at Hammondsport, the plane and A-2 were disassembled, crated, and shipped to Annapolis. The first Curtiss flew at Greenbury Point on 30 September, with Towers at the controls of A-1. Ellyson arrived in Annapolis the next day and flew A-1 over three days.

Two days later, he and Towers attempted to establish a hydroaeroplane long-distance record flight of 153 miles from Annapolis to Old Point Comfort, Virginia. After three forced landings, they barely made half the distance and had to be ferried back on board the Bailey (Torpedo Boat No. 21).

A-1 received a new replacement 75-horsepower engine on 15 October. Ellyson and Towers were then ordered to re-fly the long-distance mission. They departed on 25 October but—after two hours, two minutes, and 112 miles—were forced down at Milford Haven, Virginia. After two more forced landings, Towers flew solo the last few miles, as the engine would no longer take off with the pair on board. Despite this, they had set a two-man hydroaeroplane distance record. The return trip took four days, with radiator, carburetor, and weather issues all conspiring against them.

On 10 November, Towers took off in A-1 for its 100th recorded flight, which lasted five minutes. Later that afternoon, he and A-1 ran out of luck on the 101st flight.

A half-mile from shore, while banking in a left turn, the biplane’s rudder jammed. The ailerons could not relieve the bank, and the plane spiraled into the water. Towers jumped free of the aircraft just before it struck the water. The plane settled upside down with the pontoon above the surface. Towers received only minor injuries, but the aircraft was deemed a total loss.

The Navy, however, rebuilt what remained with stock spare parts and additions from Curtiss. A-1 was ready for flight on 19 December. The next day, Towers made four flights in the first experiments with airborne radio transmission. The trials failed because the trailing antenna was too weak. That ended flying for 1911 at Greenbury Point; the aviators received orders to transfer with their equipment to North Island. By 25 January 1912, A-1, A-2, and B-1 were in California.

Throughout late 1911, Chambers continued to push for a catapult-launch method. He garnered interest from the Bureau of Ordnance, which decided to build and test a catapult. It consisted of a modified torpedo tube and air tank, which powered a sled carrying the aircraft down a track. The catapult was installed at the Naval Academy’s Santee Dock in June 1912.

On 31 July, Ellyson in A-1 made the first launch attempt for the aircraft’s 247th flight. Unsecured to its launching cradle, the aircraft lifted off prematurely at mid-stroke. The violent release of the propelling air forced the pilot into his seat, which caused him to pull back on the wheel, pitching A-1’s nose up more than intended or required. A crosswind caught the plane, and it nosed into the Severn. Escaping serious injury, Ellyson awaited rescue on the upturned pontoon.

Barely three months later, on 12 November, he repeated the trial successfully. This time, he flew A-3 (later AH-3) from a revised float-mounted catapult at the Washington Navy Yard. This marked the first successful catapult launch of an aircraft. It was followed a month later by the successful launching of a Curtiss flying boat from the same apparatus.

By the time of the first successful launch, however, A-1 was no more. After 285 flights and numerous rebuilds, it was damaged beyond repair in a 16 October crash at Annapolis. Fittingly, the pilot most associated with the Navy’s seminal aircraft, Lieutenant Theodore Ellyson, was at the controls.