The 4th of June 1942 was a very bad day for Marine Corps aviation. At the Battle of Midway, Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 22 suffered terrible losses and contributed little to the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s spectacular victory that day. The group’s fighting squadron, VMF-221, lost far more aircraft than its pilots shot down. Its dive-bomber squadron, VMSB-241, suffered staggering losses without hitting a single Japanese ship.

Midway historians have thoroughly chronicled the actions of these two squadrons and touched on some reasons for their performance. The most cited causes are the obsolescence of Marine aircraft and the inexperience of Marine aviators.1 A closer examination of archival material reveals additional factors that impaired the group’s performance at Midway and new insights into why MAG-22 sent such green pilots into battle.

The heart of MAG-22’s troubles lay in its two competing missions: While forward deployed to defend an advanced base, the group also served as a de facto training command for new aviators. This alone would have undermined its combat readiness. But additional factors worked against MAG-22. In the weeks before the battle, the flight hours the group devoted to training were limited by its responsibilities to defend Midway Atoll and by logistical shortfalls. During the battle, Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 were unable to coordinate aircraft from three services based at the atoll. Finally, imprecise direction from Pacific Fleet commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz led to misunderstandings of how MAG-22 would employ its fighting squadron.

Present-day naval commanders are acutely familiar with the challenge of balancing combat readiness and forward presence. As naval leaders look for ways to maintain Navy and Marine Corps forces in the western Pacific and prepare for possible conflict there, the experience of MAG-22 at Midway provides a sobering reminder of the risks of attempting to do too much with too little.

MAG-22’s Very Bad Day

At 0555 on 4 June 1942, Midway’s radar detected a large formation of aircraft 93 miles northwest of the atoll. MAG-22’s siren wailed. In accordance with orders issued the previous evening by Lieutenant Colonel Ira L. Kimes, the commander of MAG-22, VMF-221 launched its aircraft immediately. A detachment of six Navy TBF Avengers took off next, followed by four Army Air Forces B-26 Marauders armed with torpedoes. The TBFs and B-26s proceeded independently to attack the Japanese carriers. The 16 SBD-2 Dauntlesses and 12 SB2U-3 Vindicators of VMSB-241 took off last and rendezvoused about 20 miles east of Midway’s Eastern Island.2

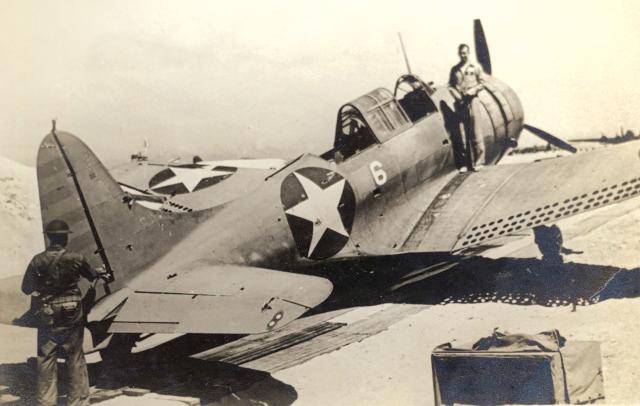

VMF-221’s commanding officer, Major Floyd B. Parks, had organized his 21 F2A-3 Buffalos and seven F4F-3 Wildcats into four divisions of Buffalos and one of Wildcats. All but one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 were mission ready and got airborne, though the divisions became slightly disorganized during the hasty scramble. The Japanese strike consisted of 108 aircraft—36 Aichi D3A “Val” dive bombers, 36 Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” carrier attack aircraft, and 36 Mitsubishi A6M2 “Zeke,” or Zero, fighters. In accordance with Kimes’ plan, MAG-22’s fighter direction center funneled all five of VMF-221’s divisions to intercept the incoming strike. The Marines had the altitude advantage, and the separate divisions launched a series of overhead gunnery passes against the Japanese bomber formations. As the slower Marine aircraft recovered for additional passes, the nimbler Zeros overtook them and sent one after another tumbling downward.3

There is little doubt VMF-221 got the worst of the fight. The Japanese shot down 15 Marine fighters and severely damaged another nine, leaving just one F2A-3 and one F4F-3 ready to fly. Though Kimes afterward estimated Japanese losses at 43 aircraft, his surviving pilots definitively claimed just nine victories. Kimes’ estimate included “probable victories by missing fighter pilots” as well as claims by rear-seat gunners of VMSB-241.4 The actual total was far lower. VMF-221 probably shot down just three aircraft outright. Another 16 Japanese aircraft survived the raid but either ditched or were so irreparably damaged they could not fly again.5

A PBY Catalina flying boat had spotted the Japanese carriers, and MAG-22 passed their location to VMSB-241.6 Major Lofton R. Henderson, the squadron commander, led the SBDs. Major Benjamin W. Norris, the executive officer, led the SB2Us. While Henderson took his unit to 9,000 feet, Norris climbed to 13,000 feet.7 On paper, the SB2U-3s were nearly as fast as the SBD-2s, but the two flights proceeded independently.8

Because the Marine dive bombers were slower than the TBFs and B-26s, had taken off last, and had flown east before heading northwest, VMSB-241 did not attack until a half hour after the TBF and B-26 attacks had ended. The Japanese combat air patrol had shot down five of the six Avengers and two of the four Marauders; none had scored a hit. When Henderson and his SBDs spotted the carrier Hiryū at about 0755, the Japanese combat air patrol still had 13 fighters aloft.9

Henderson conducted a glide-bombing attack. A dive-bombing attack would have facilitated bombing accuracy and complicated fighter gunnery and antiaircraft solutions. But more than half of Henderson’s pilots were too inexperienced to attempt the technique, and the cloud cover would have made dive bombing particularly difficult.10

The combat air patrol’s Zeros attacked Henderson first. On their second pass, they sent him down in flames. The remaining SBDs continued the gliding attack. One by one, the Marines released their bombs—and missed. Some came petrifyingly close for the Hiryū’s crew, and many Marines mistakenly believed they had scored hits.11

Norris and his Vindicators arrived at about 0820, less than ten minutes after the surviving SBD-2s had departed and amid an attack by Army Air Forces B-17 Flying Fortresses. The combat air patrol had doubled to 26 fighters. Norris descended through the clouds toward the carrier Akagi. The Zeros could not find the dive bombers as long as they were in the safety of the cloud bank, but neither could the Marines see the ships below. When they emerged at 2,000 feet, they saw only the battleship Haruna. Norris also attempted a gliding attack. The Haruna maneuvered evasively, neatly avoiding every one of the Marines’ bombs. The SB2Us hugged the surface and flew back to Midway.12 Only 8 of VMSB-241’s 16 SBD-2s and 8 of its 12 SB2U-3s returned.13

VMSB-241 conducted two more strikes during the battle. That evening Norris led five SB2U-3s and six SBD-2s in a vain search for burning carriers. They found nothing, and Norris did not return, lost in the inky, moonless squalls. On 5 June, VMSB-241 attacked the cruisers Mogami and Mikuma. The squadron lost another Vindicator to antiaircraft fire and again scored no hits.14

What Was Done Well

MAG-22 did some things remarkably well in its first action. Due to superb intelligence and early warning, no airworthy planes were caught on the ground. The fighter direction center placed the fighters in an optimum intercept position. The dive bombers located the Japanese carriers. Most impressively, every fighter and dive-bomber pilot attacked without hesitation into the teeth of a formidable defense.

MAG-22’s efforts indirectly contributed to the destruction of the Akagi and two other carriers, the Kaga and Sōryū, later that morning. As historians Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully demonstrated, the cumulative effect of the series of failed attacks by bombers from Midway and U.S. carriers created conditions that delayed Admiral Chūichi Nagumo’s counterattack and placed his carriers at greater vulnerability to the dive bombers from the USS Enterprise (CV-6) and Yorktown (CV-5). Dodging the attacks required the carriers to maneuver violently. Defending against them required the carriers to launch and recover fighters. Perhaps just as important, Nagumo faced a series of menacing dilemmas, complicating his decision-making. When the dive bombers from the Enterprise and Yorktown appeared overhead at 1020, Kates and Vals were still below on the hangar decks, where their fuel and ordnance amplified the destructive power of the American bombs.15

VMF-221 also helped reduce the strength of Nagumo’s counterpunch when it did come. The only carrier that survived the Enterprise and Yorktown dive-bomber attacks was the Hiryū. It was her air group that VMF-221 had attacked. Though the Marine fighters shot down just two Kates outright, another seven Kates were shot down by Marine antiaircraft guns, ditched, or were too damaged to participate in the strikes against the U.S. carriers.16 In other words, the Marines did not bring down many aircraft, but the ones they did bring down were the right ones—aircraft from the Hiryū’s air group.

Nonetheless, 4 June had been an awful day for MAG-22. It had lost many aircraft, shot down only a handful of the enemy, and hit no ships. Forty-two MAG-22 Marines had died; 36 pilots and gunners were missing; and six Marines had been killed in the bombing of Eastern Island.17

‘Not a Combat Airplane’

Every surviving Marine fighter pilot from VMF-221 attested to the superiority of the Zero over the Marine fighters. Captain Philip R. White pulled no punches: 8ik9o,

The F2A-3 is not a combat airplane. It is inferior to the planes we were fighting in every respect.

It is my belief that any commander that orders pilots out for combat in a F2A-3 should consider the pilot as lost before leaving the ground.18

Kimes agreed. In his endorsement to his aviator’s statements, Kimes recommended that the fleet relegate the F2A-3 Buffalo, the F4F-3 Wildcat, and the SB2U-3 Vindicator to training commands.19

The Vindicator was indeed past its usefulness. However, there is evidence that neither fighter was to blame for VMF-221’s poor performance. With improved tactics, Marine and Navy pilots would achieve far better results with the F4F in the Solomons. Captain Marion Carl, the only Marine to shoot down a Zero over Midway, believed the F2A-3 was as maneuverable and fast as the F4F-3, and its only drawbacks were that it could not absorb punishment and was less stable as a gunnery platform than the Wildcat.20

Some British and Dutch Buffalo aces, whose squadrons suffered grievously against Imperial Japanese Navy Zeros, attributed their lopsided outcome to Japanese proficiency and numbers rather than the Buffalo’s inferiority. Finnish Buffalo pilots enjoyed great success flying the planes against the Soviets.21 The Buffalo’s mixed performance in other theaters suggests that other factors contributed to VMF-221’s poor performance.

‘Half-Baked Flyers’

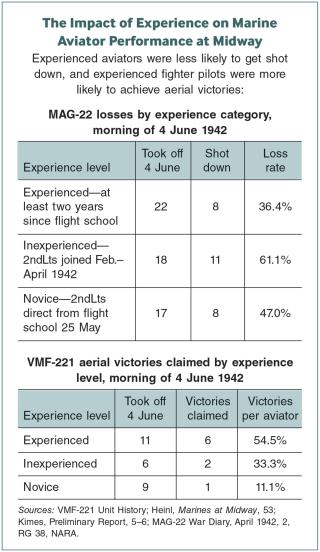

When VMF-221 and VMSB-241 had landed on Eastern Island in December 1941, both squadrons were top heavy with experience. VMF-221’s most junior pilot had been flying for at least a year since flight school.22 But the 57 aviators who flew on 4 June included 35 second lieutenants, none of whom had been with their squadron more than four months, and 17 of whom had arrived on 27 May directly from flight school.23

In the first half of 1942, Marine aviation had two conflicting missions: defending the fleet’s advanced bases and training new aviators. Newly winged aviators reported to the fleet with just 200 hours of flight time, and none in the aircraft they would fly in combat.24 The new aviators needed operational training, but the aircraft they needed to train in were defending advanced bases in the Pacific.

On 8 January 1942, Brigadier General Ross E. Rowell, the commander of 2d Marine Air Wing, described the dilemma in a letter to Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., the commander of Aircraft, Battle Force, Pacific Fleet: “I have now accumulated 35 second lieutenants in various stages of advanced training. . . . If ComAirBatFor approves and you want some half-baked flyers, send me a dispatch to that effect.” Halsey approved; he directed Rowell to order the green fliers to squadrons like VMF-221 and VMSB-241.25 This decision set in motion a sequence of personnel transfers that diluted the combat readiness of forward-deployed squadrons. As inexperienced aviators joined squadrons at advanced bases, experienced aviators left to form new squadrons in Hawaii and California.

Marine aviation was still following its prewar training pipeline. Once students were designated naval aviators, they reported to squadrons in the Fleet Marine Force for about a year of operational flight training in combat aircraft.26

Not only did MAG-22 not have a year to train its new aviators, but the group’s commitment to the defense of Midway also required it to devote most of its operational flights to patrols and radar calibration vice gunnery and tactics. Less than 30 percent of VMF-221’s missions from December 1941 to May 1942 were dedicated to improving the lethality of its fighter pilots.27

Logistics shortfalls further impinged on the group’s training. A shortage of .50-caliber machine-gun ammunition often limited gunnery practice to dummy runs.28 In the final week before combat, PBY Catalinas and B-17 Flying Fortresses drew thirstily from Midway’s fuel stocks, which were already limited due to an incredible blunder. On 22 May, demolition charges placed at an underground fuel storage facility detonated when one of the defense battalion batteries fired its 11-inch guns. The station lost 375,000 gallons of precious aviation fuel and its pipeline to Eastern Island.29 The resulting shortage prevented the group from providing the 17 Marines fresh out of flight school with anything more than familiarization flights. VMSB-241 could not even check out its new pilots in their SBDs.30

Without question, MAG-22 fought the Battle of Midway with inferior aircraft and many “half-baked” pilots. Though the odds were stacked against the group’s aviators, command decisions may have stacked the odds higher than they needed to be.

‘No Organized Plan Whatsoever’

In a 1966 interview, MAG-22’s former executive officer stated there had been “no organized plan whatsoever” to coordinate Midway’s Army Air Forces, Navy, and Marine aircraft.31 Though not strictly true, his characterization betrays how Naval Air Station Midway and MAG-22 struggled to coordinate air operations.

In anticipation of the coming fight, Nimitz had abundantly reinforced Midway. In addition to MAG-22, Midway’s air force included 31 PBYs, 17 B-17s, the 4 B-26s, and the 6 TBFs. Nimitz assigned tactical control of all these to the naval air station commander, Navy Captain Cyril T. Simard, and sent an experienced aviator and a naval base air defense detachment to coordinate air operations.32

While the naval air station directed scouting operations superbly, integrating the bombers in a coordinated strike proved beyond its reach. Each aircraft type attacked without regard to the next, permitting the Japanese the opportunity to fend off each in turn. As Kimes observed in perfect hindsight, “It would have been better had they arrived simultaneously.”33

Coordination was exacerbated by the physical separation of the naval air station and MAG-22 command posts. Simard and his air operations officer were on Sand Island; Kimes and his command post were on Eastern Island. According to Kimes’ executive officer, the “Marines ran their own show” but did not command the other services’ bombers on Eastern Island, including the six Navy TBFs.34

Kimes’ air group struggled to coordinate its own aircraft. VMSB-241 does not seem to have attempted to integrate its SBD and SB2U attacks. Most puzzlingly, MAG-22 allocated no fighter protection to VMSB-241 for its strike against the Japanese carriers.

‘Go All Out for the Carriers’

Kimes employed his fighting squadron in what Marine Corps doctrine termed “general support.” As then–Major William J. Wallace lectured Marine officers at Quantico in 1941, general support was an offensive mission that allowed fighters the freedom to be “on the prowl.” In contrast, missions that tied fighters to protection missions, such as escorting bombers, were termed “special support.” As a fighter pilot, Wallace clearly favored the freedom to go find trouble and emphasized, “The rule, then, for the employment of fighter units should be-—general support wherever and whenever possible.”35

In January 1942, now–Lieutenant Colonel Wallace took command of Marine aviation on Midway, which he retained until relieved by Kimes in April. It was Wallace who had developed the fighter direction system MAG-22 employed for defense of the atoll. As Wallace’s views on fighter employment reflected Marine Corps doctrine, and Wallace commanded MAG-22 until two months before the battle, this bias likely influenced Kimes’ decision to place all of VMF-221 in general support on 4 June.

MAG-22’s fighter employment stands in stark contrast to how Japanese and U.S. carrier task forces operated on 4 June. Carriers were far more vulnerable to air attack than an island base. Nonetheless, every Japanese and American task force commander allocated fighter escorts to increase their bombers’ chances of getting through the enemy’s fighters.

Hitting the Japanese fleet was exactly what Nimitz had in mind when he reinforced Midway with so many aircraft. On 20 May, Nimitz provided the Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet, Admiral Ernest J. King, with some views on the role of land-based aircraft he had drawn from the recent Battle of the Coral Sea:

The shore commander should assign attack missions designed to render the greatest possible assistance to the Fleet Task Force when it is engaged and should particularly be ready to provide fighter protection when it is practicable.36

Nimitz incorporated these views in his planning guidance for Midway. In a 23 May memorandum to his chief of staff, Captain Milo F. Draemel, Nimitz explicitly directed that “Midway planes must thus make the CV’s [aircraft carriers] their objective, rather than attempting any local defense of the atoll.”37 In an undated memorandum likely written about the same time, Nimitz reiterated his intent to Captain Arthur C. Davis, his air officer:

Balsa’s [Midway’s] air force must be employed to inflict prompt and early damage to Jap carrier flight decks if recurring attacks are to be stopped. Our objectives will be first—their flight decks rather than attempting to fight off the initial attacks on Balsa. . . . If this is correct, Balsa air force . . . should go all out for the carriers . . . leaving to Balsa’s guns the first defense of the field.38

But in his operations order for Midway, Nimitz was less clear in the tasks he assigned to Simard at Midway:

(1) Hold MIDWAY.

(2) Aircraft obtain and report early information of enemy advance by searches to maximum practicable radius from MIDWAY covering daily the greatest arc possible with the number of planes available between true bearings from MIDWAY clockwise two hundred degrees dash twenty degrees. Inflict maximum damage on enemy, particularly carriers, battleships, and transports.

(3) Take every precaution against being destroyed on the ground or water. Long range aircraft retire to OAHU when necessary to avoid such destruction. Patrol planes fuel from AVD [seaplane tender] at French Frigate Shoals if necessary.

(4) Patrol craft patrol approaches; exploit favorable opportunities to attack carriers, battleships, transports, and auxiliaries. Observe KURE and PEARL and HERMES REEF. Give prompt warning of approaching enemy forces.

(5) Keep Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet and Commander Hawaiian Sea Frontier fully informed of air searches and other air operations; also the weather encountered by search planes.39

The very explicit language Nimitz used in his planning guidance—that Midway’s aircraft “should go all out for the carriers”—is not reflected in his order. Absent such direction, Simard left it to Kimes to command the Marine squadrons as he saw fit. In accordance with Marine Corps doctrine, Kimes placed his fighting squadron in general support over Midway—and sent his dive bombers against the Japanese fleet without fighter escorts. Had he allocated one or two divisions from VMF-221 to escort VMSB-241, more Marine dive bombers may have survived to drop bombs on the Hiryū, and their accuracy may have improved had they attacked with less interference from the Japanese combat air patrol.

Trying to Do More with Less

MAG-22 had not gone all out for the carriers but had massed its fighters in defense of Midway. Naval Air Station Midway had struck the Japanese carriers with every bomber available but had been unable to coordinate their attacks to increase their chances for success and survival. Most tragically, many of the Marines lost in the battle were just not ready to fight the Imperial Japanese Navy, despite their willingness and eagerness to try.

MAG-22’s very bad day is a cautionary tale. Trying to do more with less—in MAG-22’s case, trying to defend Midway while training novice aviators—carries risks that may be hidden until they are exposed through combat. In his report of the battle, Kimes included a page and a half of candid comments and recommendations.40 After Midway, Marine aviators applied the lessons MAG-22 had learned at enormous cost and achieved spectacular results against the same foe in the Solomons, often under the leadership of aviators who had survived Midway.

Those same lessons are noteworthy today. Naval experts have cautioned the naval services against maintaining too much forward presence with too little fleet.41 An enduring lesson of MAG-22 may be that very bad days result from very bad choices, and that choosing to do more with less is often a very bad choice.

1. Gordon W. Prange, with Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, Miracle at Midway (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1982), 187–98, 218–22, 228–30; John B. Parshall and Anthony Tully, Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2005), 176–80, 185–88, 200–4; Richard Camp, “A Shattered Command,” Aviation History, July 2017, 50–57; Craig L. Symonds, The Battle of Midway (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 226–28, 240–42.

2. Marine Aircraft Group (MAG) 22 War History, Annex C to MAG-22 Executive Officer’s Report, 9 June 1942, 5–9, and Bureau of Aeronautics interview of LtCol Ira Kimes, 31 August 1942, 1, RG 38, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD (NARA); Col John F. Carey, USMC (Ret.), interview by Robert Barde, 1 July 1966, 1, The Battle of Midway: “Miracle at Midway,” Box 2, Folder 9.0 and 10.0, Gordon W. Prange papers, Series 7, University of Maryland Special Collections, College Park, MD (Prange papers); Rich Pedroncelli, “The Lone Avenger,” Naval History, 15, no. 3 (June 2001); Symonds, Midway, 236; “Battle of Midway: Army Air Forces,” Naval History and Heritage Command; VMSB-241, War Diary, 1–30 June 1942, 3–4, RG 38, NARA.

3. Commanding Officer, VMF-221, Report on Enemy Contact, 6 June 1942, RG 127, NARA; Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, 125–26.

4. LtCol Ira L. Kimes, USMC, Report of Battle of Midway Islands, 7 June 1942, 3, RG 127, NARA.

5. Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, 204. By scrutinizing Japanese air group records, Parshall and Tully have established an authoritative accounting of Japanese losses at Midway.

6. MAG-22 War History, 5.

7. VMSB-241, War Diary, 1–30 June 1942, 3–4.

8. Jane’s Fighting Aircraft of World War II (New York: Crescent Books, 1996 [1945]), 228; National Naval Aviation Museum, “SB2U Vindicator.”

9. Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, 154.

10. Capt Elmer G. Glidden, USMC, statement, 7 June 1942, enclosure in Commanding Officer, VMF-221 Report on Enemy Contact; VMSB-241, War Diary, 1–30 June 1942, 3.

11. Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, 178.

12. Statements by Capt Leon M. Williamson, USMCR, 2ndLt George T. Lumpkin, USMCR, 2ndLt George E. Koutelas, USMCR, 2ndLt Daniel E. Cummings, USMCR, 2ndLt Jack Cosley, USMCR, 2ndLt Allan H. Ringblom, USMCR, 2ndLt Sumner H. Whitten, USMCR, 2ndLt Orvin H. Ramlo, USMCR, 7 June 1942, RG 127, NARA.

13. Kimes, Report of Battle of Midway Islands, 2.

14. LtCol Ira L. Kimes, USMC, Preliminary Report of MAG-22 of Battle of Midway June 4, 5, 6, 1942, 4, and Capt M. A. Tyler, USMC, VMSB-241, Casualties for 4 June 1942, 7 June 1942, RG 127, NARA; VMSB-241, War Diary, 1–30 June 1942, 8.

15. Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, 154–55, 186–89, 205, 210, 215–16.

16. Parshall and Tully, Shattered Sword, 204.

17. MAG-22, War History, Annex A, Executive Officer’s Report of the Battle of Midway, “Casualty List—Personnel,” 1–2, RG 38, NARA.

18. Capt Philip R. White, USMC, statement, 6 June 1942, RG 127, NARA.

19. Kimes, Report of Battle of Midway Islands, 4.

20. MajGen Marion Carl, USMC (Ret.), interview with Benis M. Frank and Maj Gary W. Parker, USMC, 1973 and 1978, 97, Oral History Collection, History Division, United States Marine Corps, Quantico, VA.

21. Steve Ginter and Richard Dann, Brewster F2A Buffalo and Export Variants (Simi Valley, CA: Ginter Books, 2017), 108–16, 131–33, 142–49; Jim Maas, F2A Buffalo in Action (Carrollton, TX: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1987), 10–12.

22. Muster Roll of Officers and Enlisted Men of the U.S. Marine Corps, Marine Fighting Squadron 221, 1–30 April 1942, retrieved from ancestry.com. All the squadron’s second lieutenants held regular commissions. The most junior, Francis P. McCarthy and Philip R. White, accepted regular commissions on 2 December 1941. Because they had to complete 12 months’ active duty to qualify for regular commissions, they must have earned their wings by December 1940.

23. VMF-221, Unit History, 23–24, RG 127, NARA; LtCol Robert D. Heinl Jr., Marines at Midway (Washington, DC: Historical Section, U.S. Marine Corps, 1948), 53; Kimes, Preliminary Report of MAG-22 of Battle of Midway, 5–6.

24. Navy Department General Order Number 65, 10 August 1921, cited in Bureau of Aeronautics, Marine Corps Aviation, vol. 20 (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1957), 68, 112.

25. Letter, Rowell to Halsey, cited in Robert Sherrod, History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II (San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, 1980), 54.

26. Commander Aircraft Battle Force, Carrier Aircraft, vol. 1, USF-74, Current Tactical Orders and Doctrine U.S. Fleet Aircraft (Pearl Harbor, T. H.: United States Pacific Fleet, March 1941), Section 2-302, 106; Maj William J. Wallace, USMC, “Fighting Aviation,” 4, Personal Papers Collection, Lectures, Collection 3983, Box 10, Marine Corps Schools, 1940–41, Folder 20, Records of the Archives Branch of the U.S. Marine Corps History Division, Quantico, VA.

27. VMF-221 War Diaries, 30 November 1941–31 March, April, and May 1942, RG 127, NARA.

28. LtCol Ira Kimes, interview by Bureau of Aeronautics, 31 August 1942, 14, MAG-22 War History, RG 38, NARA; VMF-221 War Diary, April and May 1942, RG 127, NARA.

29. U.S. Naval Air Station Midway Island War Diary, 14 July 1942, 4, RG 38, NARA.

30. Henry I. Shaw, Verle E. Ludwig, and Frank O. Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, vol. 1, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958), 220.

31. LtGen Verne J. McCaul, USMC (Ret.), interview by Robert Barde, 1 June 1966, 1, The Battle of Midway: “Miracle at Midway,” Box 2, Folder 9.0, Box 3, Folder 3.0, Prange papers.

32. Command Summary of FADM Chester W. Nimitz, USN (Nimitz Graybook), vol. 1 of 8, 547, Papers of Chester W. Nimitz, Archives Branch, Naval History and Heritage Command, Washington, DC; Symonds, Midway, 211; Office of Naval Intelligence, Battle of Midway June 3–6, 1942 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1943), 6.

33. Kimes, interview by Bureau of Aeronautics, 3.

34. McCaul interview by Barde, 1 June 1966, 1.

35. Wallace, “Fighting Aviation,” 6–8.

36. Nimitz Graybook, vol. 1, 487.

37. Nimitz memorandum to CAPT Milo F. Draemel, USN, 23 May 1942, cited in Heinl, Marines at Midway, 23.

38. Nimitz to CAPT Arthur C. Davis, USN, undated, quoted in Heinl, Marines at Midway, 23. “Balsa” was the code name for Midway.

39. Commander-in-Chief, United States Pacific Fleet, Operation Plan No. 29-42, 27 May 1942, 7–8, midway42.org/Features/op-plan29-42.pdf.

40. Kimes, Report of Battle of Midway Islands, 4–5.

41. See The Honorable Robert O. Work, “A Slavish Devotion to Forward Presence Has Nearly Broken the U.S. Navy,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, 147, no. 12 (December 2021); LT Jeff Zeberlein, USN, “Can-Do Is Not Working,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 12 (December 2021).