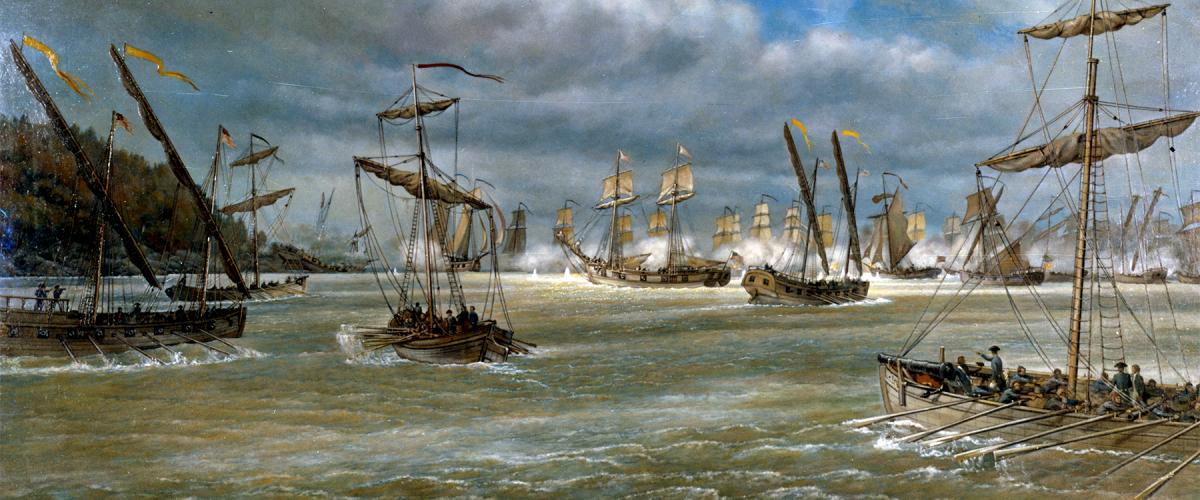

It is widely accepted today that the only truly influential battle fought by the fledgling U.S. Navy during the Revolutionary War was fought on Lake Champlain—the engagement known today as the Battle of Valcour Island. America at this time did not have a navy as we understand it: A fleet of ships-of-the-line commanded by experienced admirals. Rather, it was a force born out of necessity and commanded by that most controversial of men, Benedict Arnold—a man who, at the time, was on the cusp of becoming a great hero of the revolutionary cause. His defense at Lake Champlain held back the British invasion of Canada and bought the Continental Army time to form up and win at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777—before, of course, he turned traitor.

Arnold had long realized that to defeat the British, American forces would need to meet them and defeat them both on land and at sea. On their retreat from Quebec, the Patriots, under Arnold, had carefully destroyed all the ships on Lake Champlain to ensure that they could not be used by the British. Arnold’s rear force had abandoned Fort Saint-Jean; he burned everything, denying the British the ability to cross the lake and continue their invasion.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

With no vessels available in the lake, Patriot commander Gates and his British counterpart both set about building their own fleets. Although this task initially was given to Gates, it soon became Arnold’s job to command the effort, which was spearheaded by the shipwrights at Skenesborough, New York, where Wood Creek empties into the narrow head of the lake on its southern side. Today, it is the site of the shipyard at Whitehall.

When Arnold arrived in July 1775 there were more than 200 shipwrights working at Skenesborough under the watchful eye of Hermanus Schuyler and his chief military engineer Jeduthan Baldwin, all of whom were employed to build an American fleet. Philip Skene had founded the town and the early shipyard, which contained a wooden dam, a bridge, water powered sawmill, grist mill, forge, and a foundry, as well as carpenters and copper and farrier shops. Local quarries provided the stone for Skene to build himself a manor house and bands of iron ore, which led him to claim that his men could “turn out the best iron bar(s) in the colonies.” In addition to these resources, 30 carpenters from New York came from Skenesborough to join the shipbuilding effort, followed by around another 100 from Connecticut and Massachusetts, all of whom allowed for the fleet’s rapid construction.

General Philip Schuyler had reported to Washington that one ship could be produced every six days—a target that was to prove rather optimistic. Worker morale was low and there were smallpox and malaria outbreaks among the carpentry teams. The boats Schuyler had in mind were gundalows or gondolas—large, open boats that were flat bottomed and could be rowed or sailed, depending on the conditions. General Gates had written to Arnold, stating he was “anxious to have you here as soon as possible,” although he did not specify what Arnold was going to do when he arrived.

The first ship was launched just before Arnold’s arrival on 26 June 1776.

On his arrival, Arnold found two gondolas under construction and on another slipway the frame of a row galley. This type of row galley was about 70 feet long—much longer than the gondolas and much more like a proper schooner than the gondola, which, in many ways, was simply a large rowboat. The row galley was round bottomed, square sterned and, much like the larger contemporary man-of-wars, they had a proper gun deck and raised quarter deck. The vessels also had two fully rigged masts, making them much more maneuverable and reliable than the basically rigged gondolas. Arnold much preferred these row galleys and intended they be equipped with 24 18-pound guns. He immediately realized the row galleys would be much more effective than the gondolas and ordered a second one to be constructed based on his clear specifications. While recognizing what had already been achieved, Arnold wanted everyone to focus on row galley construction and another three were ordered. Gates was happy to cede command of all naval operations to Arnold, being impressed with his ambition and drive calling him the “most gallant and deserving officer” for such a position.

Although historians, and Arnold himself, have credited him with the direct supervision of the fleet construction, Arnold spent a lot of time travelling between Skenesborough and Ticonderoga, where the ships were receiving their final fittings. He also spent a good deal of time at Mount Independence, where other defenses were rapidly being built. Arnold also was helping in the frantic scramble for supplies and stores for the men because, as Arnold wrote, “the vessels cannot be completed until the blocks and cordage arrive.” He drew on his contacts from his time as a merchant sailor in Connecticut to help meet these shortages. Arnold also knew he needed more men, specifically more experienced sailors and knew how to maneuver the galleys. Privateers at the time could earn a great deal of money working on private vessels; by contrast, in Arnold’s own words, the prospect of sailing on the fledgling fleet on Lake Champlain offered men only “fatigue and danger.”

Back in the shipyard, by the end of July, Arnold is generally credited with the idea of mounting mortars on two of the gondolas, with the intention of sailing them to St Johns to end the British shipbuilding there before it had really begun. The plan was a good one, but it failed when the mortar shells proved weak and split on firing, spraying the gun deck with potentially lethal shrapnel. This failure led him Arnold to increase his pursuit of supplies, meaning he was often away from Skenesborough for days at a time. When Arnold arrived back on 6 August, he was very happy with what he found. Three galleys were nearing completion—the Washington, Schuyler (later renamed the Trumbull), and Lee—but even better news was that the Congress, the ship with which Arnold would soon become synonymous, had been launched.

The Congress had been built by Thomas Casdrop, a carpenter from Philadelphia; however, she was not yet complete and was immediately sent to Ticonderoga to be properly fitted out. The Congress was joined by three gondolas, but soon shipbuilding activities largely came to a halt. Supplies were again hard to come by, and even more alarmingly disease—most likely malaria— had broken out. Arnold also had other worries; he was dealing with the court martial of Moses Hazen, who he accused of disobeying his orders regarding provisions on the retreat from Canada. The court sided with Hazen and wanted to convict a furious Arnold for contempt and ordered his arrest. Commander Gates, however, knew Arnold’s worth and dissolved the court stating, “he (and the patriot cause) must not be deprived of that excellent officers service.” Arnold had made no secret of the fact that he wanted to take over command of the fleet being constructed at Skenesborough and Gates made it no secret that he desperately wanted Arnold to do so.

Command was duly given to Arnold, but Gates was keen that he was not given entirely free rein. He told Arnold he could go no further up the lake than his orders specified, nor could he leave the main fleet to launch raids against the British. More to Arnold’s taste was Gate’s evocative order that if the British should come up the lake, then he must “defend the pass with such cool determined valour as will give them reason to repent their temerity.” This was Arnold’s hour, and he knew it.

The Congress also was now prepared for hers. She was fully fitted out, ready to sail, and was launched on 1 September.

By now, the British were buoyed with confidence having won a clear victory at the Battle of Long Island, and on 2 September Arnold received word that the British were four miles away at the other end of the lake. Despite a fair degree of panic, the fleet was able to sail north mostly unmolested and soon it was at Windmill point, where the lake narrows into the River Richelieu. The fleet began to encounter more and more British and their allies. Scouting parties sent ashore revealed to Arnold that the wooded banks were swarming with enemy soldiers. The British wanted to lure Arnold up water and into a trap, something he steadfastly resisted with uncharacteristic restraint. The next few weeks passed in a state of increasing tension; Arnold was aware that the British fleet was growing stronger, he repeatedly sent men on scouting missions to gather intelligence, and two schooners patrolled above and below his fleet. He was granted permission by Gates to move further south to Isle la Motte, but soon changed his mind and decided instead to make for Valcour Island where, in his own (paraphrased) words, he said “if the Americans succeeded in their attack the British could not escape, and if the Americans were bested the retreat would be open and free.”

All the waiting was taking its toll, though, and by the end of September the Americans were beginning to wonder if the British would make any move at all that year. Morale was lifted by the arrival of the fitted out galley Trumbull on 30 September, which joined the fleet at Valcour Island. The British at last began to move in early October. Their fleet set sail and headed from Cumberland Bay, where they hoped to locate the Americans; to their dismay, they could not see them. Arnold had chosen his spot well, for although they could find no trace of the Americans, they were barely seven miles away from them.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

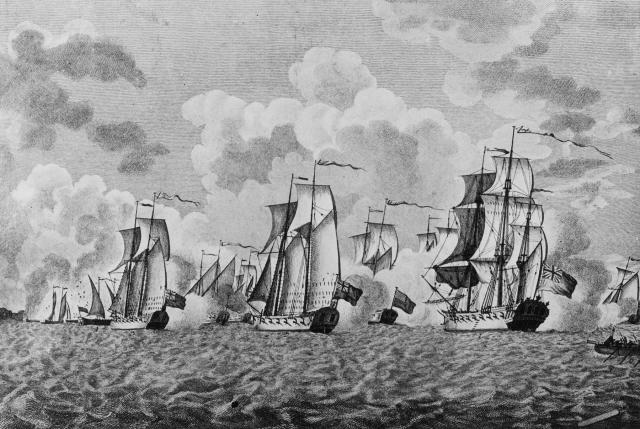

The ships were spotted by Arnold’s scouts, and he met with his chief officers, General David Waterbury and Colonel Edward Wigglesworth, to determine a strategy. They feared being trapped by the British and knew the time to fight was upon them. Up until this point, Arnold had chiefly sailed on board the Royal Savage, but now he transferred to the Congress, which he declared the flagship of the fleet. Arnold then ordered the gondolas to form up in a defensive line. The galleys and the Royal Savage were sent out, for what purpose is unclear, and it was the Royal Savage that was first sighted by the British in the morning. By 1000, the British fleet was on the east side of Valcour Island. They quickly set about pursuing the Americans, sending in their gunboats first. The Congress, Washington, and Trumbull sailed back to Valcour Bay, where they anchored in a battle line. If the British wanted to pass, they would now have to get through the Patriot line.

Arnold had been wise to make the Congress his flagship; the unfortunate Royal Savage was far less able to maneuver. She was forced aground and caught fire. The fighting picked up and, in the words of Arnold, “became very fierce” before noon. The American guns were far less effective than the British, who had 30 guns now firing into the American line. Arnold, however, had positioned his fleet well and the British struggled to maneuver with ships not designed for battle as such a confined area. Nevertheless, the guns took a terrible toll on the American fleet. Arnold personally took to firing the Congress’s guns as men began to flounder and fall. The Congress lay right at the center of the line and as such made a tempting target for the enemy. Her sides were shredded by incoming cannon balls and her main mast and yard took serious damage. By nightfall ammunition on both sides was running low, so the British made a tactical withdrawal. The Royal Savage sank, and her crew decamped to the battered Washington. The damage to the patriot fleet was assessed as the loss of the ship Philadelphia, severe damage to all other vessels, and about 60 men dead. The situation was desperate. Arnold knew they could not survive another day's pounding, and so it was decided that they should attempt to slip away.

The Trumbull led the retreat under row not to sail, so as not to alert the British. Arnold’s Congress was the last ship to leave. The smoke from the Royal Savage’s smoldering hull helped to screen the retreat, but soon the wind changed and it became much more difficult for the ships to move with the wind against them. They limped on to Schuyler’s island, but Arnold knew they could not remain there. By the next day, 12 October, the British were already in pursuit. Arnold’s crews were exhausted, meaning that it was not until 1400 that the Congress began to move slowly away. The British knew the American fleet would not be able to escape. It became a case of what tactics would best delay the British and buy time for American forces on land. They pushed on through day and night with the Congress making ten miles on 13 October before she anchored again. She was just 28 miles north of Crown Point, so torturous their flight had been. Soon after daybreak, Arnold saw the “British fleet were very little way above Schuyler’s island. . . . we gained very little by beating or rowing due to the wind breezing up from the southward.” The Washington, in a terrible state, fell behind; Arnold, however, refused permission for her to be destroyed. She was to limp on and join the rest of the fleet if she could. She could not, and at 0900, her Captain David Waterbury was forced to surrender to the British.

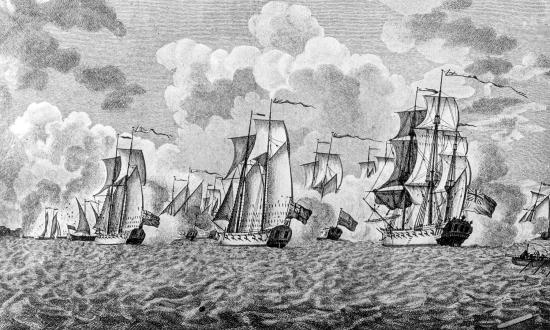

The British now moved against the Congress. She was attacked by the fastest British ship, the Maria, pounded with grapeshot and surrounded in a matter of minutes. Forty-four British guns were brought to bear against the Congress’s 18 plus ten swivels. Nevertheless, the Congress fought for nearly three hours, trying to buy the American fleet time to escape before she attempted a fighting retreat. Arnold reported that all the while the British “kept up incessant fire on us with round and grapeshot,” but that he was making a stand. Arnold’s deputy and many others were killed, and the Congress’s sails, rigging, and hull were smashed to pieces. By noon she was barely afloat, but Arnold did not intend to surrender; he turned the Congress and the four surviving gondolas east, into what was then called Ferris Bay, and ran them aground. He then ordered the men ashore. According to eyewitness accounts the last man to leave was Arnold himself. From the shore the Americans set the ships alight, Arnold noting proudly that, despite everything, they had not “struck their colors,” i.e., surrendered. The Congress burned quickly. Arnold and his men meanwhile headed on foot to Crown Point, pursued by native British allies. The American fleet, and with her Arnold’s Congress, were no more, but the real consequences of their actions that day would soon be felt.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

The Naval History and Heritage Command states that the Congress’s role in delaying the British “played a key role in (aiding) the next year's defense at Saratoga” and the bravery displayed by Arnold and his men was a “most powerful factor in influencing France to throw her might including the large French navy on the side of the struggling young republic.” The actions of Arnold and the Congress soon became legend. Today, a spindle made from the wood of this first Congress in Henry Sheldon's relic chair is a major tourist draw, and five more ships would go on to bear her name proudly. Arnold, meanwhile, for now the hero of Lake Champlain and later Saratoga, would ultimately go down in history for quite a different reason.

List of sources/further reading:

Benedict Arnold, Proceedings of a General Court Marshall for the trial of Major General Arnold (1865), www.openlibrary.org.

Benedict Arnold, Selected Letters, www.founders.archives.gov

Joyce Lee Malcolm, The Tragedy of Benedict Arnold (New York: Pegasus Books, 2018).

James Melvin, A Journal of the Expedition to Quebec: In the Year 1775, Under the Command of Colonel Benedict Arnold (Washington, DC: Library of Congress,1857).

James Nelson, Benedict Arnold’s Navy: The Ragtag Fleet that Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain but Won the American Revolution (Camden, ME: International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press, 2006).

Sam Willis, The Struggle for Sea Power: A Naval History of American Independence (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2016).