The examples of the past can offer validity in the present. Today’s U.S. Navy, the world’s largest, has tried to find historical precedents for its modern dominance. In the process, early American naval leaders such as John Paul Jones have been practically beatified at the U.S. Naval Academy, where each new class of midshipmen is required to learn the Jonesian “Qualifications of a Naval Officer” by heart. This preoccupation with the heroic Jones persists despite his general absence from the seminal works of that great maritime prophet Alfred Thayer Mahan. The reality is that, regardless of Jones’s exploits, the only truly influential battle fought during the Revolutionary War by an American naval force occurred not on the high seas, but on a lake.

The Battle of Valcour Island was not one of ships-of-the-line and admirals, but of galleys and inexperienced seamen. The man in charge of the rebel fleet on Lake Champlain was Brigadier General Benedict Arnold—a brilliant asset to the Revolutionary cause before he turned traitor. His defense of Lake Champlain in 1776 held back a British invasion from Canada, giving the Continentals valuable time to reform their armies and achieve decisive victory at Saratoga in 1777.

In the public’s memory, the patriots’ ingenuity at Valcour Island is overshadowed by American naval battles with HMS Serapis or Guerriere, the clash of ironclads at Hampton Roads, or glory won at Midway and Leyte Gulf. The 21st-century fleet, though, is not without reminders of its humble origins. In August 2017, steel was cut for CVN-80, a ship that will bear the name Enterprise. Her pedigree hearkens not only to the other modern Enterprises. Eight vessels have borne that proud name, and the new ship will carry the legacy of those crews. With stories of the “Big E,” though, it is little wonder many have forgotten that the first Enterprise was a lowly sloop, one of only five American ships to survive the “strife of pigmies,” as Mahan dubbed it, on Lake Champlain. How fitting that a name dating to a time when the success of the American experiment was still undetermined will once again serve as reminder of the pivotal—though often overlooked—role the Continental Navy played in winning a nation’s freedom.

Arms Race on Lake Champlain

The importance of the 11 October 1776 Battle of Valcour Island underscores the geographic and strategic value of Lake Champlain. From tribal warfare long before the Europeans arrived, down through the French and Indian War, the mighty lake had served as a north-south water highway through the wilderness for rival forces. After the failure of the American invasion of Canada in 1775, Arnold retreated to the southern end of the lake. There, he convened a council of war on 7 July 1776. He persuaded those assembled “that the most effectual measures [should] be taken to secure our superiority on Lake Champlain by a naval armament of gundolas, row gallies, armed batteaus.”1

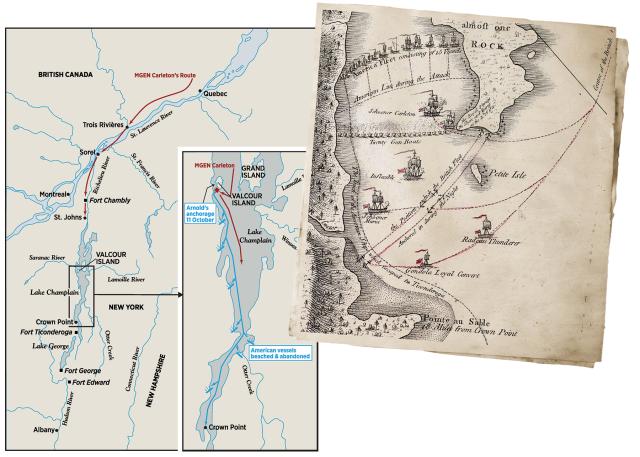

The lake extends 145 miles north to south and had been a major means of transportation from the earliest days of colonization. The combined effect of Lake Champlain, Lake George, and the Hudson River is that New England, except for a small piece of land, is, strategically speaking, an island. This “consecutive waterline . . . of communication from the St. Lawrence to New York” was a key strategic objective of the British Army. The British goal was to divide the colonies in two through naval control of Champlain and the Hudson, isolating troublesome New England. Major General Guy Carleton, governor of Quebec, would advance south from Canada to join General William Howe’s army at Albany and “thereby cut off all communication between the northern and southern colonies.”2

Carleton’s original plans predicted his occupation of New England before the beginning of winter. The tactical threat posed by even a small number of Continental ships on the lake, however, meant the British required a naval contingent.3 Carleton adopted a strategy of overwhelming force against the Americans, but amassing the force took time he did not have.

Rapids along the Richelieu River, which flows between the St. Lawrence River and the north end of Champlain, prevented ships from sailing southward into the lake. Carleton therefore ordered three ships be painstakingly dismantled, transported, and reassembled. Two of these mounted 6-pounders, the Maria and Carleton. The third was the imposing 18-gun Inflexible. He acquired ten gunboats, disassembled, from England, augmented by ten of his own newly constructed gunboats. His most unusual construction was the Thunderer, a flat-bottomed craft capable of transporting 300 men and armed with six 24-pounders and six 12-pounders. A gondola captured during the American retreat from Canada and renamed the Loyal Convert joined the fleet. Thirty longboats and approximately 400 bateaux for soldiers and supplies, which were to follow once Arnold had been confronted, completed the invasion force.4

Wanted: Instant Armada

The American commander faced difficult odds but was suited for the task. Benedict Arnold is best known (aside from his infamy as a traitor) for his military actions on land, but his father was an experienced sailor who owned and captained his own merchant ships. Arnold followed this example, trading extensively in the West Indies before the war. His ingenuity, coupled with a basic understanding of seamanship, would compensate for a lack of formal naval training.5

Arnold was confronted with a similar problem of constructing a fleet quickly. In July 1776, his navy consisted of only four ships: the Enterprise, a sloop seized during the capture of Fort Ticonderoga; the Royal Savage, a schooner captured during the invasion of Canada; and the Revenge and Liberty, also schooners. Major General Horatio Gates referred to this small flotilla as “the American Navy.” In adding to this force, Arnold encountered a logistical problem. He had an inexhaustible amount of timber all around him, but few shipbuilding tools or craftsmen who understood how to use them. Arnold sent out a call for skilled men and supplies, but they were slow in arriving.6

Arnold knew he would not be able to match Carleton’s ships in firepower, so he built vessels for speed and maneuverability, favoring the row-galley. The galleys stretched 70 feet in length with a beam of 18 feet. For propulsion, they were fitted with two masts supplemented by 36 oars. In choosing the galley design, Arnold accounted for the inexperience of his men in the technical art of seamanship as well as the independence the oars offered from the wind. “The galleys,” he recorded, “are quick moving, which will give us a great advantage in the open lake.”7

In late August, Arnold set out to train his inexperienced navy. For seven weeks he taught the 700 soldiers under him the basics of naval warfare. By October, Arnold’s armada totaled 17. His original four had been joined by the cutter Lee and the gondolas New Haven, Providence, Boston, Spitfire, Philadelphia, Connecticut, Jersey, and New York. These flat-bottomed boats offered little besides quick construction and expendability. They each mounted two 9-pounders and one 12-pounder and were manned by a crew of 45. Three row-galleys—the Trumbull, Washington, and Congress, Arnold’s flagship—completed the assortment.8 They were mainly armed with an assortment of 18-, 12-, and 6-pounders.

As he prepared his men, Arnold also searched for a location to fight. He quickly realized the tactical advantages offered by Valcour Island. The island, just south of the Canadian border, was covered by dense woods tall enough to conceal his fleet. Its proximity to the western shore created a protective cove off its northern end. In planning the engagement, Arnold ordered men to measure the water depth and found an anchorage of suitable depth protected by a rocky channel unnavigable for Carleton’s largest ships. By positioning his ships here, Arnold forced Carleton to travel the entire length of the island past his position and then, after spying him, turn back north into the wind. This redirection would disrupt the formation of the British squadron.9

Carleton also prepared for the battle. He sought the tactical advantage through intelligence gathering. For weeks his men updated the British commander on Arnold’s movements on the lake. Carleton was aware of the Continentals’ gunnery practice and even of Arnold’s tactic of using the branches of fir trees tied to the side of the ship as a shield against musket fire and boarders. By 4 October, Carleton had assembled a force of 13,000 men to reclaim the lake for King George.

Showdown on an October Morn

Carleton’s flotilla was composed of 30 to 34 ships manned by 670 professional seamen, 19 petty officers, and eight officers. One thousand British soldiers, who were to serve as boarding parties, followed in 40 bateaux, along with 650 American Indians in canoes. Carleton continued to be very calculating in his movements, slowly advancing and using his Canadian and Indian allies for reconnaissance.10

On the morning of 11 October, the understandably confident British commander made a tactical mistake that changed the course of the battle: He elected not to send scouting parties ahead. Because of this decision, he sailed south past Valcour Island, unaware of the 15 vessels and 700 men lying in wait.

The same morning at 0800 the rebel schooner Revenge, patrolling ahead of the main fleet, spotted the head of the British squadron. On seeing the enemy’s strength, Arnold’s second in command urged retreat, since fighting from the cove would trap the American fleet. Mahan criticizes this suggestion as having “its origins in that fruitful source of military errors of design, which reckons the preservation of a force first of objects, making the results of its action secondary.”11 Indeed, Arnold understood that survival of his fleet was not an inherent part of his operational objectives.

Arnold’s plans initially proved successful. The larger American vessels sailed windward to attract British attention and, if possible, achieve a raking position. The British ships sailed two miles past the hidden American fleet and became aware of Arnold’s presence only when the Congress and Royal Savage emerged accompanied by row-galleys. The Enterprise, Lee, and the remaining gondolas formed a defensive semicircle behind.12

Slowly, the British came about to face their opponent. The adverse winds meant that Carleton’s largest ships, the Maria and Inflexible, were able to come no closer than the distance for long-range firing. The other boats did not fare much better. Only the Carleton pursued the Americans. When Arnold saw that the British had turned and committed to the fight, he signaled for his ships to return to their line. The superior mobility of the row-galleys immediately was apparent. When confronted with strong winds from the north, the crew simply lowered the sails and rowed. Arnold’s largest vessel, the Royal Savage, was not equipped with oars and was intractable in the northerly wind. She ran aground, and Carleton’s ships concentrated their fire on her.13

The men on board the schooner tried to escape onto the island, but a boarding party from the gondola Loyal Convert captured 20 of the American crew. The British then were able to turn the Royal Savage’s guns on the American fleet. Shortly after noon, the Carleton sailed into the cove followed by 17 gunboats. They proceeded to attack the defensive arc created by the Americans.

The Carleton offered a large target for Arnold’s gunners. Soon the ship was incapacitated and towed from battle. The Inflexible took her place broadside the Americans. The ensuing exchange would have been enough to finish the American fleet had darkness not ended the day’s carnage.

The British ships formed a line from the tip of Valcour Island to the New York shore. The captured Royal Savage was burned in accordance with Carleton’s orders, and casualties were counted. The British had lost about 60 men. Carleton was confident the following morning would see the demise of the short-lived American naval presence on Lake Champlain.14

Desperate Moment, Daring Breakout

That evening, Arnold met with his officers and took stock of his fleet. The American forces had suffered a casualty rate of nearly 10 percent, principally because of the fire from the British gunboats. The gondola Philadelphia had been sunk. Other vessels were still floating but had suffered heavily: The Congress was hulled 12 times and the Washington even more. The New York had lost all her officers. Arnold understood that remaining in the cove would mean destruction or surrender. Escape was the only option.15

The lake that night was shrouded in a dense fog—but not before Arnold discerned a break in the British lines. He prepared his fleet for the escape by moving the wounded into cabins where their cries would be muted. Each vessel was fitted with hooded lantern attached so that each became visible only when viewed directly from the stern to signal the following ships. Oars were muffled, and longboats towed the sailing ships. Led by the Trumbull, the American fleet slipped through the British line, undetected. One British observer credited Arnold, saying “this retreat did great honor to General Arnold who acted as Admiral to the Rebel Fleet on this occasion.”16

As the sun rose on the 12th, the Americans were nearly eight miles from the cove. The British commander was infuriated to find his quarry had fled. Both Arnold and his pursuers were impeded by a southerly wind. Ten miles south of Valcour Island, the Americans anchored at Schuyler’s Island to conduct hasty repairs. At this point the men had not slept for more than 30 hours, six of which were filled with uninterrupted fighting.17

The Americans sailed through the night of 12–13 October, but at sunrise, the British ships were in sight. The row-galley Washington, Arnold’s trailing vessel, found herself within four miles of the enemy. Her commander asked to scuttle the galley, but Arnold insisted the Washington continue on her course. Soon the British were within firing distance of the galley and she capitulated. Arnold would report, “The Washington galley was in such a shattered condition and had so many men killed and wounded she struck to the enemy after receiving a few broadsides.” Arnold’s flagship, the galley Congress, was only a mile ahead.18

The American commander would not be able to run much longer. Carleton’s schooner Maria, largely unscathed from the previous day’s battle, chased the Congress, with the Inflexible and Carleton following close behind. The combined firepower of 44 enemy guns with round and grapeshot pounded the doomed Congress. Arnold could reply with nothing more than eight big guns and ten swivels, combining to only 82 pounds. Still he refused to surrender. The three British ships were within musket range, and still the Congress fought. For two and a half hours the British forces thus were occupied while the other remnants of the American fleet dashed for safety.19

The running battle between the Congress and the British overtook the gondolas Boston, Providence, New Haven, and Connecticut, which joined the struggle. Within ten miles of the American guns at Crown Point, Arnold realized escape was hopeless and beached the Congress and gondolas. The rebels clambered ashore, with Arnold being the last to disembark, and the vessels were set ablaze, the ensign of the new nation, the Grand Union flag, still flying gallantly above the inferno.20

Toward Saratoga

Of the 16-ship navy with which Arnold had been entrusted, all but five were lost in less than four months. The Enterprise, Trumbull, New York, Revenge, and Liberty were still afloat, but Lake Champlain had fallen under British control.21 The Battle of Valcour Island, however, must not be evaluated by these statistics alone. Its effect on the entire war should be viewed from the perspective of the following year’s campaign.

As Arnold’s men retreated farther south to Fort Ticonderoga, Carleton established his position at Crown Point. The fort there, burned by the Americans, was unsuitable for the coming winter, and Carleton, refusing to push farther south and attack Ticonderoga, returned to Canada to launch the invasion the following year. But 1777 would see Carleton replaced by Major General John Burgoyne. In the interim, the British had achieved complete control of the lake north of Ticonderoga. Simultaneously, the American forces had reinforced their position.22

In early July, Burgoyne and nearly 10,000 soldiers marched on Ticonderoga. The defenders understood that holding the fort was hopeless and withdrew during the night of 5–6 July.23 The Battle of Saratoga that followed was a series of engagements beginning on 19 September, throughout which Arnold again earned the title of hero. Finally, on 17 October, General Gates and nearly 15,000 soldiers and militiamen surrounded Burgoyne’s remaining force of 5,895 at Saratoga. Burgoyne surrendered. This major victory by the Continental Army reinvigorated colonial desires for independence. More importantly, it resulted in the recognition of the United States by King Louis XVI of France. Spain and the Netherlands followed. Foreign involvement would prove a key ingredient in the eventual triumph of the American rebels.24

Tactical Defeat, Operational Success

The Battle of Valcour Island had ended in a tactical defeat for Arnold, with Carleton controlling the lower portion of the lake. Indeed, in England, Carleton’s victory at Valcour Island was enthusiastically greeted as such, and the commander was rewarded with knighthood. In America, the response to Arnold’s actions was mixed.25

Operational success, however, was not contingent on a tactical victory. The mission of the fleet was always to stall the British advance until winter. Arnold, therefore, had accomplished most of his operational goals simply by building a fleet that required Carleton’s attention. Overall, Arnold had employed a Fabian strategy of denial—denial of ready control of the lake. And he led the British warships on a protracted chase that resulted in the escape of a portion of the Americans.

Baron Friedrich Riedesel, who commanded Carleton’s German troops, realized the importance a mere month had had in the outcome of the campaign: “If we could have begun our expedition four weeks earlier . . . everything would have been ended this year [1776]; but, not having shelter nor other necessary things, we were unable to remain.”26

Ironically, four weeks was the amount of time taken by the British to build the Inflexible, a ship whose overwhelming presence was superfluous—because of a stubborn leader and his small navy.

1. Philip Schuyler. “Resolves of a Council of War Held at Crown Point,” in William James Morgan, ed., Naval Documents of the American Revolution, vol. 5 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1970), 961.

2. Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence (London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Limited, 1913), 7, 14.

3. John A. Barton, “The Battle of Valcour Island,” History Today 9, no. 12 (1959): 794–95; John R. Bratten, The Gondola Philadelphia and the Battle of Lake Champlain (College Station, TX: Texas A&M Press, 2002), 58.

4. James L. Nelson, Benedict Arnold’s Navy: The Ragtag Fleet that Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain But Won the American Revolution (Camden, NJ: McGraw Hill, 2006), 7.

5. Barton, “The Battle of Valcour Island,” 793.

6. Mahan, Navies, 14.

7. “A List of the Navy of the United States of America on Lake Champlain Aug. 7th, 1776,” in Naval Documents, vol. 6, 96–98.

8. Barton, 794.

9. “Captain Charles Douglas to Philip Stephens,” in Naval Documents, vol. 6, 1344–45; Bratten, The Gondola Philadelphia, 58; Barton, 796.

10. Barton, 96.

11. Mahan, 19.

12. Bratten, 58.

13. Nelson, 296.

14. Bratten, 65.

15. Bratten, 64.

16. Bratten, 67.

17. Nelson, 311.

18. “Brigadier General Benedict Arnold to Major General Philip Schuyler,” in Naval Documents, vol. 6, 1275; Nelson, 316.

19. Nelson, 317.

20. Bratten, 69.

21. John P. Milsop, “A Strife of Pygmies: The Battle of Valcour Island,” MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History 14, no. 2 (2002): 86–90.

22. Milsop, “A Strife of Pygmies,” 94.

23. Brendan Morrissey, Saratoga: Turning Point of a Revolution (Westport: Praeger, 2004), 32.

24. Morrissey, Saratoga, 86.

25. Bratten, 72; “Gen Horatio Gates to Gen Benedict Arnold,” in Naval Documents, vol. 6, 1237; James Kirby Martin, Benedict Arnold, Revolutionary Hero: An American Warrior Reconsidered (New York: New York University Press, 1997), 288.

26. Mahan, 13.