Contraband Peter, age 19, born in nearby Nachitoches, likely didn’t have a last name when he enlisted on board the U.S. ram Avenger on the 24th of October 1864 at Donaldsonville, Louisiana.

Possibly “Donelson” had a good enough, familiar sound, so he was assigned “Peter Donelson” as his full name. At 5’8”, the enlistee recorded as “African American, negro, black,” was of average height among his crew mates. In ship muster rolls, his occupation was reported as “slave.” Peter was designated “1st Class Cabin Boy,” the lowest rank in the U.S. Navy, usually attached to sailors under 18.1

Like other little towns up and down both sides of the Mississippi River during the Civil War, Donaldsonville had sustained severe damage during attacks as Union and Confederate armies fought to occupy their positions. Assigned to the Lower Mississippi Squadron, one of the Avenger’s duties in May 1864 was blockading the waters between Morganza and Donaldsonville. A steamboat with large cargo capacity and enough room to install a few cannon, the vessel originally had been acquired by the Union Army for the Mississippi Marine Brigade. She was retrofitted into an oaken hull ram boat but was turned over for service in the “Brown Water Navy.” The Avenger carried dispatches, provided gunboat backup during battle, and conducted occasional shore raids, confiscating supplies, munitions, and cotton.2

It is unclear whether Peter was one of the several hundred slaves whom the Avenger had freed. But his enlistment marked an act of courage—an official entry into the great struggle—that served as an example for his kin, friends, and community to follow.

‘The Pressing Need for More Men’

Devastation, destruction, and loss of life during the “War of the Rebellion” touched nearly every American. Slavery was among the top issues, if not the main one. Still, it was business as usual as far as racial discrimination in the U.S. Navy. Black men were signed on as cabin boys with lower pay. They were limited in service to lower positions such as servants, cooks, assistant gunners, etc., on board vessels.

That being said, responsibilities would be shifted if a white man got sick. And as the pressing need for more men to fight the war increased, the percentage quota of black men compared to white men on a ship went up from 5 percent to as high as 24 percent.3 Segregation and menial labor pushed upon black sailors did vary, however, from one ship to another, depending on the personalities of the officers. On board a ship, every man’s contribution was essential.

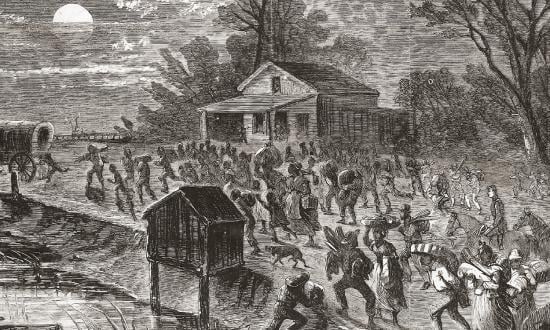

Union Navy recruitment of contrabands was carried out quietly.4 Controversy had evolved over the enlistment of fugitive slaves who sought safety on Union ships. “Although the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, requiring that fugitive slaves be returned to their owners, was in effect when the war began, it was not strictly enforced. . . . Major General F. Butler refused to return runaway slaves because, he argued, “the Union and Confederacy were at war, and the slaves could be contraband of war.”5 Thus, African Americans who went from slavery to enlistment in the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army came to be known as “contrabands.”

While some crew members may have thought little of their black shipmates, officers soon learned how valuable they were. Most of them were accustomed to hard work, discipline, the humid climate, and poor living conditions. Slaves belonging to the plantations along the Mississippi could act as guides and provide information about the waterways, as well as Confederate movements and resources. It is estimated that, as of 1 October 1864, there was a total crew of 115 men on board the Avenger, and that the number of “negroes” was 19.6 According to Acting Paymaster E. J. Huling in his Reminiscences of Gunboat Life in the Mississippi Squadron, several contrabands interested themselves in learning to read and write (which was illegal for slaves), but hardly one white sailor was interested.7 A few female contrabands served in the Union Navy as well, on board the hospital ship USS Red Rover, in both domestic menial jobs and medical care.8

The Specter of Disease

Disease and infection caused two-thirds more casualties and death in the Civil War than combat. In the Navy, where personal cleanliness was expected and living conditions were slightly better than on land, those numbers were greatly reduced. Contaminated water was widespread. Medical technology was at least ten years behind weaponry advancements. Antibiotics weren’t discovered yet, and quinine was increasingly difficult to come by. Anesthesia was used in the form of chloroform, ether being too flammable.

On board ship and in land hospitals, there was much not much space, poor ventilation, and ghastly latrine setups, which intensified the ever-present typhoid fever, yellow fever, smallpox, pneumonia, tuberculosis, syphilis, dysentery, and infection. Doctors, caregivers, and patients who survived would never escape the mental anguish of pain, groaning, coughing, crying, misery, fear, and despair—cleanliness becoming less and less possible, the knowledge of sterility, nil.

The minor diseases, if one could call them that—measles, mumps, chicken pox, whooping cough, parasites, scarlet fever, etc.—were clearly evident as well. Civil War records are dotted with diagnoses of “debility” or “debilitus,” which usually meant weakness or needing a break—these days it would probably be described as post-traumatic stress disorder.

David King—African American, born in North Carolina, occupation slave, ranked 1st Class Cabin Boy—at the age of 40 was approved by the Avenger’s Acting Assistant Surgeon, Dr. Jabez Henry Moses, to the Pinkney naval hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, shortly after he enlisted, for chronic rheumatism.9 One of David’s white shipmates, Stephen J. Green, born in New York City, ranked engineer, also was transferred to Pinkney, diagnosed with syphilis.10 Dr. Moses, as per protocol, inventoried each patient’s clothing and belongings. See Table 1.

These accounts would have been reflective of what supplies most sailors were issued upon enlistment. With few variations, the gear would not have been that different from what the Confederate Navy used.11 Since the men would have been required to pay for their own gear, it was usually garnished from their wages, which took about three months. It probably took David longer, since he would have been earning “boy” wages. As enslaved young males quite often only wore long shirts until they attained manhood, three pairs of trousers would have been a real achievement. Shoes to fit swollen, cracked, and possibly infected feet may have been something else.12

Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter ordered that only enough clothing was to be given to black sailors in the Mississippi Squadron to make them comfortable, until they were out of debt. Furthermore, they should be kept distinct from the rest of the crew.13 Ironically, slaves from some plantations not only picked the cotton, but spun it and made clothes for their masters and themselves as well. Nicholas Ford, for example, was a spinner, but when he signed on with the Avenger in Natchez, he was assigned “Coal Heaver.”14

Keeping the Coals Burning

It may be a toss-up between the engineers, firemen, and coal heavers to name the real heroes on board the Avenger. The engineers and their assistants would have been constantly monitoring and cleaning the system from engine to boiler room. The firemen kept the coals burning. “The coal heavers climbed into cavernous bunkers and heaved mountains of dusty, dirty coal into the boilers. Their jobs were filthy, dangerous, and hot . . . temperatures soared above 120 degrees.”15 The coal consumption to keep these kinds of steam vessels moving has been estimated to be almost a ton an hour. The Avenger moved at about 10.4 knots, or about 12 miles per hour. The engines in such a sidewheeler burned the coal to heat water in boiler tubes for creating steam. When the steam was held and released through the opening and closing of a valve, pistons were enabled to lift and drop—generating the power behind the paddles.16

Above or belowdecks, it seemed the whole vessel was a sweatbox. If it was hell in a hammock in berthing, it would have been stifling hot as Hades working with the engines and boilers. It was here that most African Americans ranked 1st Class Cabin Boys would have been assigned on the Mississippi Squadron’s ships.

Green Magee is one of those coal heavers on board the Avenger that we know a little about. Arleen, one of his descendants, who is a paralegal, genealogist, and writer, was surprised and pleased to recently learn about Green and his Civil War service. Green enlisted in Black River, Louisiana, occupation slave, and was of course ranked 1st Class Cabin Boy.17 It is possible that Green took the “Magee” surname from the Nehemiah Magee and Celia Roberts plantation near Mount Hermon, Louisiana. Nehemiah Magee served in the Louisiana State Legislature and had voted for secession from the Union. Some of the African American family members on the extended Green Magee family tree show having been born in Mount Hermon and Log Town.18 According to Roberts’ family records:

After Nehemiah’s death, [in 1868] Cecelia managed their plantation and (ex) slave labor force near Mt. Hermon with efficiency. She was a kind mistress over her slaves. With the end of the war and freedom of her slaves, most of the Blacks remained on the place and worked for her in“freedom.” Some remained there and worked for until her early death in 1887. She was a “liberated” woman and knew how to exist in a man’s world.19

Green Magee and his wife Olitippa (Tippa), however, settled and raised their family in Ascension after the war. Green worked at odd jobs and as a laborer, and Tippa kept house.20 After Green passed away in 1917, Tippa applied for his seaman’s naval pension, and, as she had previously, for his soldier’s invalid pension in 1899.21 He had served his patriotic duty.

Moses Culpepper, born in Ouachita Parish, previous occupation slave, enlisted on board the Avenger in Monroe, Louisiana. After the war, he and his wife, Julia Potter, returned to Ouachita Parish, where he worked as a farmer, drayman, and laborer.22 Julia’s descendant, Shaniqua, was surprised and excited recently to discover her distant ancestor’s ties to the Civil War. Moses was noted in the June 1890 “Special Schedule, Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, etc.,” for Ward 4, Ouachita, Police Jury Ward, Louisiana, “Moses Culpepper (col) Rank Private, Avenger”.23

Moses and Julia added to their biological family a stepdaughter named Roxanna Culpepper. Roxy was the biological daughter of slaveholder Robert Mallory Culpepper and a slave named Fanny. (Culpepper served as a sergeant in the Confederate Army and was held as a prisoner of war in Memphis until exchanged in 1865.)24 Roxy grew up to marry William H. Tillmon Jones.

“Born a free man in Ohio in 1846, Jones moved to Vicksburg after his service in the Civil War and assisted blacks in the community as Grand Chancellor of a local chapter of the international benevolent group Knights of Pythias,” according to the Vicksburg Post. “He was instrumental in helping blacks pay for burial expenses, raise money for cemeteries, purchase insurance, and supported black-owned business enterprises.” In the basement of Bethel AME Church, he cofounded Campbell College, which eventually would become part of Jackson State University.25

Darryl, the great grandson of Roxanna Culpepper and William H. Tillmon Jones, and his wife Patricia, both attorneys and university professors, have continued forward in building up the legacy and integrity of the black community.

Thomas and Bruce Garrett, both from Ouachita Parish, Louisiana, occupations listed as “farmer and laborer” (i.e., slave) enlisted on board the Avenger in Monroe.26 Four years apart in age, it is not known if they were brothers. They could very well have taken the surname “Garrett” from the nearby Lindwood Plantation owned by Isaiah Garrett and Narcissa Grayson Garrett. The Garretts were a well-known founding family of Monroe.

“Isaiah [Garrett] retired from law in 1857 to his estate called Lindwood. He had a reputation of being an honest, upright citizen and everyone thought well of him,” according to his biography at Find a Grave.com. “It was that reason why, in 1861, he was called to represent Ouachita in Louisiana’s Secession Convention. Garrett lobbied hard as a cooperationist, and warned the convention that it would be a long and bloody war if Louisiana seceded. He was one of only seven men that refused to sign the ordinance of secession.

“Garrett returned to his beloved Lindwood and prepared for war. Because of his vision, Isaiah could not serve the Confederacy as a soldier, but he served in other ways. Two sons were sent to serve the Confederacy. Isaiah became chairman of the state military board. After his service there, he returned to Ouachita and established a private hospital for wounded and sick Confederate soldiers all the way to the end of the war.

“After the Civil War, Isaiah came out of retirement and practiced law again. He became a well-known Democrat and fought against Reconstruction right up until his death.”27

Garrett’s ledgers from his legal practice and his plantation named a few of his slaves and itemizes their financial value. Rachel, her children, and hands with smaller children were worth $2,017.50.28 Observed also was a Frank Garrett, born in Big Selma, Louisiana, a “fieldhand,” not serving on board the Avenger, but on board the USS Pinkney.29 In April 1864, the Avenger had participated a gunboat raid in Monroe, during which the courthouse, the railroad depot, some outbuildings, and a bridge were burned out. Naval records note 3,000 bales of cotton having been confiscated and about 800 African Americans freed.30 Very likely, several slaves who enlisted at the Union Navy rendezvous in Monroe survived this raid.

In her diary entry for Friday night, 15 April, young Sarah Lois Wadley of Ouachita Parish described the devastation left by the Yankees:

We heard the news Tuesday evening and on Wednesday morning Father and Mother went to town, the Yankees had indeed gone, taking all the cotton they could get, and from five hundred to a thousand negroes, almost everyone in Monroe lost their house servants, and some lost all on their plantations. Mrs. Stevens had not one house servant left except her old carriage driver, Cuffy. Mrs. Tucker’s little servant girl did not go. . . . The day that Mother was there Mrs. Tucker and Mary prepared the dinner, their servants did not leave until Monday night and left everything prepared for breakfast. Scott was very honourable, she has her Mistresses’ Silver in her charge but took none of it away with her. . . .

Mrs. Garrett is the only lady who lost none. Five of the railroad [worker] negroes left, three of whom we thought the most faithful, Nate, Little Cuffy and Ike, who all, especially Nate, behaved so well on our way to Georgia. I believe he was promised a Captaincy, perhaps that allured him, [at home] we lost but one negro, Little Emmaline, who was hired in Monroe with her husband, a railroad boy, and left with him.

Before leaving town the Yankees burned the Court house, the railroad bridge over the Ouachita and one other small public office, they did not trouble private property at all except to take all the cotton they could find. I was surprised to hear of so many negroes going, it is said that one woman killed her little baby, who was very sick, and she knew would keep her from going, many left their little babies on the plantation to go.31

The Mrs. Garrett to whom Sarah refers may very well have been Narcissa F. Grayson Garrett, wife of said Isaiah Garrett, who was well known as a leading lady in Monroe society. Sarah’s father was a railroad man, having moved to the area to supervise the construction of the Southern Mississippi Railroad.

Of the Garrett men, we know that after the war, in December 1866, Bruce was admitted for about two weeks to the Louisiana Freedman’s Bureau Hospital, for diarrhea.32 The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands was established in March 1865 to help in the reconstruction of the South. Short-funded, short-staffed, and with too few field offices, the Bureau advocated for the black community. The program was intended to address relief for the poor, black and white, in the form of food, clothing, and medical care; regulate labor conditions, represent clients in civil disputes, investigate property ownership, and set up educational programs.

Poor treatment of slaves by former owners as well as program officials was rife. It could in no way adequately care for the thousands who needed help. One of the great successes of the program, though, was the opening of schools for black people.33 However, the devastation in general could not be whitewashed. The emancipation of the slaves and the collapse of the plantation economy led to malnutrition, rampant disease, and everything but a healthy workforce.34 African Americans most often traded slavery for lives of poverty, destitution, bigotry, and racism. In all hope, Thomas Dredson—born in Marion, Georgia, and a 1st Class Cabin Boy on board the Avenger, was admitted in the U.S. Freedman’s Hospital on 3 January 1866 and received some relatively decent care.35

Contrabands—Plus Free Black Enlistees

Not all of the 22 African Americans serving on board the Avenger were contrabands from Louisiana. James Robinson, born in Louisville, Kentucky and enlisted in Albany, New York, is noted as having the former occupation of “boatman” and managed to rank as a steward in the Avenger.36 Henry Johnson—born in Georgetown, Ohio, enlisted in Cincinnati, Ohio—was previously a cook.37 Thomas J. Wetmore of New York was a former hat presser and servant. At 4’11”, he was probably the shortest sailor on board the Avenger. Most of the crew mates, black and white, averaged between 5’7” and 5’8”. It was a common practice to require short-term commissions and no promotion opportunities for black sailors. Thomas’ naval record, with ten re-enlistments at usually three, months each, bears this out.38

Though the Avenger relied on black sailors for manpower to fill out her crew, recognition for their service is sparse. (Up to eight men in the U.S. Navy after the Civil actually received Medals of Honor. A former slave from Natchez, Landsman Wilson Brown, received his Medal of Honor for valorous service on board the USS. Hartford, David Glasgow Farragut’s flagship.)39 It becomes apparent from Navy records, that less than half of the African Americans who served took advantage of veteran hospital care or applied for pensions, for various reasons. Thankfully, the father of Ouachita-born Stephen Cashborn, a coal heaver on board the Avenger, did apply for Stephen’s pension, on 18 May 1891.

Representing his 21 other African American crewmates and the legacy that they left, is one Ephraim Jackson, buried in the Vicksburg National Cemetery in Vicksburg Mississippi. Born in Ouachita, ranked 1st Class Cabin Boy on board the Avenger, he had passed away ion 9 April 1904.40 His wife, Florence, was also buried in the Vicksburg National Cemetery 15 years later. This was a great honor.

Edwin Dunham wrote in his letter “Bayou Sara La., Ram Avenger, June 12, 1864”:

The contrabands which have been onboard are quite an institution. Many a hearty laugh have I enjoyed at their pranks when not at work. And again my thoughts have been carried far away to my northern home and the church wherein I used to worship by hearing them sing such good old church hymns as “Come thou font of every blessing.”41

And today, the Avenger contrabands’ descendants, and many others as well, hold thanks for the memory of them—and are inspired to build on and keeping pushing their legacy of courage and hope.

1. Ancestry.com. Last modified August 2021. Peter Donelson in the Web: US, African Americans the Civil War Sailor Index, 1861–1865. Original data from: National Park Service. Civil War. Search for Sailors Database. African American Sailors,

2. Avenger I (Sidewheel ram) 1861–1865, Naval History and Heritage Command, Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (DANFS), https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/a/avenger-i.html.

3. Michael Davis, “‘Many Of Them Are Among My Best Men’: The United States Navy Looks At Its African American Crewmen, 1755–1955,” dissertation abstract, Kansas State University, 2011.

4. Dwight Hughes, “Slaves and Sailors in the Civil War,” Black History Month, 28 February 2018, Emerging Civil War.

5. Barbara Brooks Tomblin, The Civil War on the Mississippi: Union Sailors, Gunboat Captains, and the Campaign to Control the River (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2016), 10.

6. Herbert Aptheker, “The Negro in the Navy,” The Journal of Negro History 32, no. 2 (April 1947) 169–200.

7. E. J. Huling, Reminiscences of Gunboat Life in the Mississippi Squadron (Saratoga Springs, NY: Sentinel Press, 1881), 87–98.

8. Myron J. Smith Jr., After Vicksburg: The Civil War on the Western Waters, 1863–1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2021), 41–42; David Dixon Porter, “U.S. Mississippi Squadron, Flagship Black Hawk, off Vicksburg, July 26, 1863,” Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894–1922), Series 1, Volume 25, 327–28.

9. Ancestry.com, Last modified August 2021. David King, in the U.S. Naval Hospital Tickets and Case Papers, 1825–1865, https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/5929:2999?tid=&pid=&_phsrc=WAv659&_phstart=successSource]; David King. National Park Service, Civil War, Search for Sailors Data Base: African American Sailors.

10. Ancestry.com. Last modified August 2021. Stephen J. Green, U.S. Naval Hospital Tickets and Case Papers, 1825–1855; National Archives Catalog, Archives.com, Muster Rolls of USS Augusta Dinsmore, 1864–1865; USS Avenger, 1864–1865; USS Azalea, Stephen J. Green, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/134411369.

11. Ron Field, “To Defend Their Rights Afloat—Clothing the Confederate Enlisted Sailor—Confederate Navy Gray, Part IV, Civil War Navy 10, no. 2 (Fall 2022): 38.

12. Katie Knowles, “Fashioning Clothing: Slaves and Clothing in the U.S. South, 1830–1865,” doctoral thesis, Rice University, May 2014.

13. Maj Don A. Mills Sr., USMC, “African American Sailors: Their Role in Helping the Union to Win the Civil War,” master’s thesis, Marine Corps University, 2001–2002.

14. National Archives Catalog, Record Group (RG) 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007, Series: Muster Rolls of U.S. Naval Ships 1/1/1860–6/9/1900, File Unit: Muster Rolls of USS Augusta Dinsmore, 1864–1865; USS Avenger, 1864–1865; and USS Azalea, 1864–1865.

15. Michael J. Bennett, Yankee Sailors in the Civil War (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 35.

16. U.S.S. Cairo Engine & Boilers (Vicksburg, MS: the American Society of Mechanical Engineers and the U.S.S. Cairo and Museum, Vicksburg National Military Park, 1990).

17. National Archives Catalog, RG 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007, Series: Muster Roll of U.S. Naval Ships 1/1/1860–6/9/1900, File Unit: Muster Rolls of USS Augusta Dinsmore, 1864–1865; USS Avenger, 1864–1865; and USS Azalea, 1864–1865, Green Magee; National Park Service, “The Civil War,” Search for Sailors Data Base: African American Sailors, Green Magee.

18. FamilySearch.org. Last modified September 2022. Green Magee (May 1849–7 August 1917) married to Olitippa (1852–n.d.).

19. E. Russ Williams Jr., “The Kemp, Turner, and Roberts Families on Little Silver Creek, Washington Parish, Louisiana,” 563.

20. FamilySearch.org. Last modified September 2022. Green Magee (May 1849–7 August 1917) married to Otilippa (1852–n.d.).

21. Ancestry.com. Last modified September 2022. U.S., Civil War Pension Index: General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934. Green Magee.

22. National Archives Catalog, RG 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007. Series: Muster Rolls of U.S. Naval Ships 1/1/1860–6/9/1860. File Unit: Muster Rolls of USS Augusta Dinsmore, 1864–1865; USS Avenger, 1864–1865; and USS Azalea, 1864–1865, Moses Culpepper. Last modified September 2022. Moses Culpepper (1834–1910) married to Julia Potter (1837–before 1910).

23. Ancestry.com. Last Modified September 2022. Moses Culpepper in the 1890 Veteran Schedule of the U.S. Federal Census.

24. Ancestry.com. Last modified September 2022. Robert M. Culpepper in the U.S., Civil War Soldiers 1861–1865; Ancestry.com. Last modified September 2022. Robert M. Culpepper in the U.S., Civil War Prisoner of War Records, 1861–1865.

25. “Black History Events Honor Past,” The Vicksburg Post, 1 March 2015; FamilySearch.org. Last modified September 2022. Roxanna Culpepper (1861–1923) married to William H. Tillmon Jones (1848–1906).

26. National Archives Catalog, RG 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007, Series: Muster Rolls of the U.S. Naval Ships 1/1/1860–6/9/1860. File Unit: Muster Rolls of USS Augusta Dinsmore, 1864–1865; USS Avenger, 1864–1865; and USS Azalea, 1864–1865, Thomas Garrett and Bruce Garrett; National Park Service, “The Civil War,” Search for Sailor Database: African American Sailors, Bruce Garrett and Thomas Garrett.

27. Find a Grave, Isaiah Garrett Sr. (1812–1874) and Narcissa Grayson (1816–1890), including Biography.

28. Isaiah Garrett, “Practicing Law and Plantation Ownership in Antebellum Louisiana."

29. National Park Service “The Civil War,” Search for Sailor Database: African American Sailors, Frank Garrett.

30. “Avenger I (Sidewheel ram), 1864–1865,” DANFS.

31. H. H. Thomas, blog posted 15 April 2015, “The Civil War Day by Day,” Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, Sarah Lois Wadley Papers, no. 1258, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

32. FamilySearch.org. Last modified September 2022. Bruce Garrett. United States Freedman’s Bureau Hospital and Medical Records, 1865–1872.

33. “Freedmen’s Bureau, March 3, 1865–1872,” Virginia Commonwealth University Libraries, Social Welfare History Project.

34. Jim Downs, Sick from Freedom: African American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction, abstract (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), https://academic.oup.com/book/36000.

35. Ancestry.com. Last modified September 2022. Thomas Dredson in the U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Records, 1865–1878] National Archives Catalog, RG 24, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007, Series: Muster Rolls of Naval Ships 1/1/1860–6/9/1900, File Unit: Muster Rolls of USS Augusta Dinsmore, 1864–1865; USS Avenger, 1864–1865; and USS Azalea, 1864–1865, Thomas Dredson.

36. National Archives Catalog, RG 24, Records of Naval Personnel, 1798–2007, Series: Muster Rolls of Naval Ships, 1/1/1860–6/9/1860. File Unit: Muster Rolls of USS Augusta Dinsmore, 1864–1865; USS Avenger, 1864–1865; and USS Azalea, 1864–1865, James Robinson, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/134411369; National Park Service, “The Civil War,” Search for Sailors database: African American Sailors, James Robinson.

37. Search for Sailors database: African American Sailors, Henry Johnson.

38. Search for Sailors database: African American Sailors, Thomas J. Wetmore.

39. John V. Quarstein, “African American US Medal of Honor Recipients During the Civil War— Part I: The U.S. Navy,” Mariners’ Blog, Mariners’ Museum and Park, 18 February 2021.

40. Find a Grave, Ephraim Jackson (1843–9 April 1904), Vicksburg National Cemetery; FamilySearch.org. Last Modified September 2023. Ephraim Jackson. United States Census of Union Veterans and Widows of the Civil War, 1890. Warren, Mississippi; National Park Service, “The Civil War,” Search for Sailors Database: African American Sailors, Ephraim Jackson.

41. William Edwin Dunham, “Letter from the USS Ram Avenger, Bayou Sara, 12 June 1864,” Edwin Dunham Letters, Anderson Township Veterans, Anderson Township Historical Society, Cincinnati, OH.