Early in the spring of 1862, the USS Young Rover was operating near Lancaster County, Virginia, where the Rappahannock River empties into the Chesapeake Bay. She was part of the U.S. Navy’s North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Her task: throttle Confederate maritime traffic and communications along the coast and local riverways. But some encounters fell outside of the standing orders.

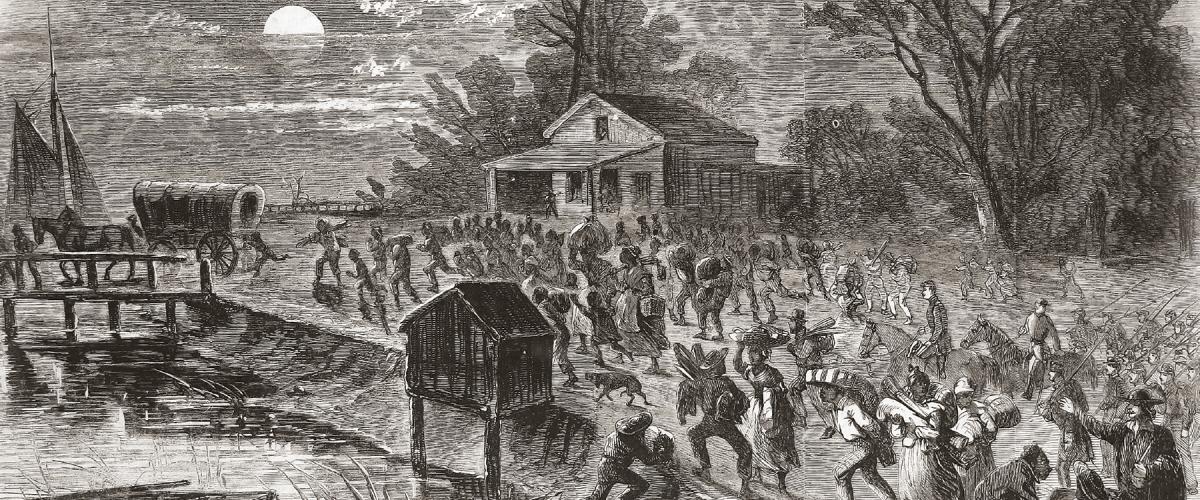

Since early in the Civil War, slaves had fled farms and overseers for the sanctuary of nearby U.S. Army camps and the prospect of freedom. Others sought refuge on board Navy ships operating on nearby waterways—de facto floating islands of U.S. territory. Federal policy was evolving regarding runaways, and Union officers exercised great discretion in deciding whether to shelter these people under the provisions of a law called the Confiscation Act.

The Young Rover’s acting master, Ira B. Studley, behaved no differently, harboring those who had fled slavery. But arriving in the mail that May was an unusual batch of letters; it would seem the disaffected owners now wanted their human property back.1

But with the beginning of hostilities, some abolitionist-minded Union generals operating in Southern districts had begun to institute emancipation policies on their own initiative despite any official directives. Many in Washington desired immediate emancipation, but freelancing generals could not be tolerated. For President Abraham Lincoln, enforcing existing slavery-related laws was often an uphill fight. Lincoln viewed the conflict as a “rebellion” within the borders of the sovereign United States, where laws were to be enforced, even if unpopular, throughout the whole nation, North and South. The Fugitive Slave Act mandated runaway slaves be returned to their masters. This proved irksome to enforce, given the complex and dynamic political forces at play in wartime. But restoration of the Union, not emancipation, was the President’s first priority.2

The ‘Contraband of War’ Solution

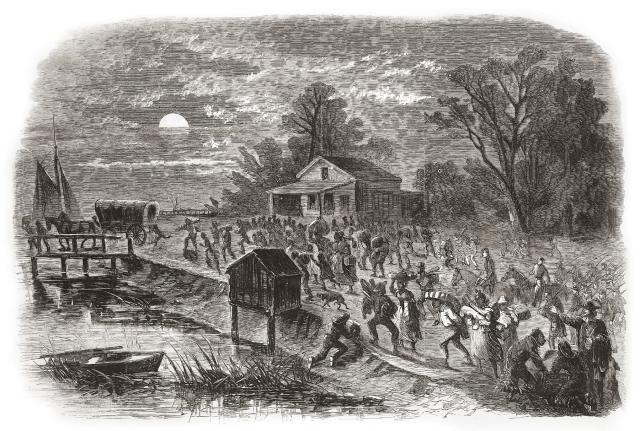

Legal justification for full emancipation was shaky at best, but Major General Benjamin Butler, a New England attorney in civilian life, provided the rationale while in command at Fort Monroe—that vital piece of Virginia territory at Hampton Roads that never left Union hands. By the summer of 1861, hundreds were fleeing across the Union line there to escape slavery, and slaveholders clamored for their return under the auspices of the Fugitive Slave Act. But the lawyer-turned-general came up with an artful argument: If these human beings were to be considered property, then as such, that meant that they were legitimate “contraband of war” if they were helpful to the Confederate war effort, and thus did not have to be returned.

This rationale made sense and took hold; henceforth, the term “contraband” became synonymous with runaway slaves.3 Congress provided additional legislative muscle to the “contraband” notion with passage of the Confiscation Act of August 1861, which focused on depriving insurrectionist masters of their human chattel. Slaves employed by Confederate masters in work regarded as hostile to the United States could be seized under this act. The War Department further concluded if a master was deemed disloyal, all labor by his slaves would be assumed to be anti-governmental in nature. It was against this backdrop that U.S. troops and ship captains eventually operated. The Confiscation Act read in part:

. . . any property of whatsoever kind or description, with intent to use or employ the same . . . in aiding, abetting, or promoting such insurrection or resistance to the laws, or any person or persons engaged therein; or if any person or persons, being the owner or owners of any such property, shall knowingly use or employ . . . all such property is hereby declared to be lawful subject of prize and capture wherever found; and it shall be the duty of the President of the United States to cause the same to be seized, confiscated, and condemned.4

As runaways sought refuge in U.S. Army camps and U.S. Navy ships, many officers felt morally bound to accept them. While slaves wandering into an Army camp certainly posed challenges, the reality of shipboard life put additional and extraordinary burdens on Navy crews who now had to billet these unscheduled passengers on already cramped vessels. Nor were slaves the only ones finding their way to U.S. ships. Free blacks, deserters, and white Southern Unionists also sought sanctuary on board these vessels.5

Naval officers were frequently sympathetic to the plight of the enslaved. More than 325 naval officers, greater than half the service, had “traitorously abandoned the flag” at war’s outbreak, leaving most remaining Federal skippers sharing the North’s negative attitudes about slavery and secession.6 Captains saw the act of turning away escaped slaves and other fugitives as unthinkable; certain severe punishments, or worse, awaited any refugees they might turn away. Oliver S. Glisson, commanding the USS Mount Vernon, harbored several runaways in July 1861 because he was positive that “if they should be returned, they would be murdered.”7

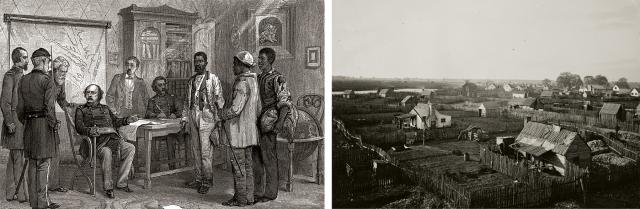

Union Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles’ position regarding runaways soon became well known throughout the fleet: “Under the circumstances no other course than that pursued by Commander Glisson could be adopted without violating every principle of humanity,” he noted, adding that returning slaves would be “impolitic as well as cruel.”8 But despite Welles’ and the Navy’s sympathy for the slaves’ plight, both the Secretary and the Navy were ill-prepared for the influx of runaways still to come.

Slaveholders Seek a Loophole

As their numbers grew, those who had fled to freedom were housed in a number of camps that sprang up; the first and largest, the Grand Contraband Camp, was located outside Fort Monroe.9 Runaways collected by the blockading vessels were brought here. Reports compiled in the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies indicate a considerable strain on Navy resources. A 16 February 1862 directive from the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron Commander, Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, stated: “As it is absolutely impossible for us to accommodate more contrabands on board of our already crowded little vessels, I have to direct that no more of them are to be received on board any vessel of the Navy now in these waters. Be good enough to communicate this order as early as practicable to all commanding officers concerned.”10 This would not be Goldsborough’s last order on the subject.

Seven weeks later, the USS Young Rover was operating near the mouth of the Rappahannock River off Lancaster County, Virginia. She was a 141-foot, 418-ton sail bark with steam auxiliary drive, outfitted with four 32-pounder guns and one 12-pounder pivoting Sawyer rifle, and crewed by 139 men and officers.11 Despite Goldsborough’s February order, the master and crew of the Rover took aboard several groups of runaways—men, women, and children—on 6 and 7 April.12

Acting Master Studley of the Young Rover had no evidence beyond the assertions of the runaways that they had been employed building “any fort, navy yard, dock, armory, ship, entrenchment, or in any military or naval service whatsoever,” as required by the Confiscation Act.13 Captains knew of Secretary Welles’ sympathetic attitude and felt at ease accepting contrabands onto their ships with few questions asked.

By the second week in April, the Rover had roughly 30 escapees on board. On 12 April, Flag Officer Goldsborough issued orders for other ships to rendezvous with the Rover, transfer various stores and provisions to her, take off the freedom-seeking passengers, and transport them to the Grand Camp. He dispatched the USS Minnesota to the Rappahannock River with the instructions, “On your arrival there, deliver the stores to the Young Rover and take from thence the contrabands she has on board, whom you will bring to this place as soon as possible.” He concluded with an emphatic addendum: “Tell the commanding officer of the Young Rover to receive no more contrabands on board till further notice from me.”14

Goldsborough must have thought himself the only officer wholly dedicated to maintaining the blockade and supporting military actions inland with his squadron on station and ready for action. He was a man vexed, caught between captains who saw little choice but to accept endangered contrabands onto their ships and a Secretary of the Navy who was more than willing to push the boundaries of the Confiscation Act. Frustrated by the seemingly endless requests for instructions regarding this or that new group of runaways, Goldsborough again emphasized in May that “all officers under my command are to be governed by the printed instructions furnished them with regard to contrabands. Unless contrabands can be rendered of use to the naval service, they are not to be received.”15

Dispossessed slaveholders, hearing of Goldsborough’s prohibitive orders, now inferred an opportunity to recover their property. The Rover had orders not to receive slaves but yet she had done so; this was a loophole the erstwhile owners hoped to exploit. In early May, Studley received no less than nine letters from various slaveholders requesting return of their property—property they believed had been taken without justification, against standing orders, and in conflict with the Confiscation Act.16 B. B. McKenney’s letter was typical of the plaintiffs’ requests:

DEAR SIR: . . . on the 7th of April, 1862, seven of my slaves left me and went on board the ship Young Rover. . . . Sir, I am a private and peaceable citizen. I have never borne arms against the United States, nor have I any child or near friend who has. In the commencement of these troubles I voted for the Union candidate and labored hard for that cause, and made many enemies by it. The 2d day of April we had a meeting and passed a resolution (unanimous) that we would offer no military defense to the Northern Army. With these considerations, I appeal to you to have my property returned. I am a farmer, and have been in the business of wood cutting for five years, and have a large contract with Oliver H. Booth, of New York, at this time. I have 1,200 cords of wood on hand all ready for market, but must lose it if my servants are not returned. I have seen the captain of the Rover, Captain John B. Studnall [sic]. He is a gentleman of fine feelings, and I think if this property is returned he is calculated to make many friends to the Union. . . . [the runaways] were taken after the order was issued to take no more, and at the time there was not a man in Lancaster in arms against the Federal Army.17

What was curious about the sudden wave of correspondence was that the letters received by Studley had distinctive similarities, indicating the owners collaborated or otherwise had been coached—most suggestive by the universal misspelling of the commanding officers’s name as “Studnall.” Each letter took care to detail the location and circumstances of their slaves’ leaving. Critically, most letters stressed that neither any of the slaves nor any of their owners had any involvement in rebellious activities—a critical stipulation of the Confiscation Act.

“These servants have never been engaged in working on any public works or fortifications of any kind. I am a farmer and peaceable citizen, and have never borne arms against any government,” wrote James W. Gresham. If reasoned legal arguments were not enough, some letters sought to play on emotions. “I am a widow in small circumstances,” penned Louisa Dunton, “and as the said Mary was the only woman I had, her loss to me is very great.”18 Not to be outdone, Gresham wrote, “Was my health not so feeble I would do myself the honor of visiting you on board of your steamer. As this cannot be, I hope you will be so kind as to use your influence for the restoration of my property.”19

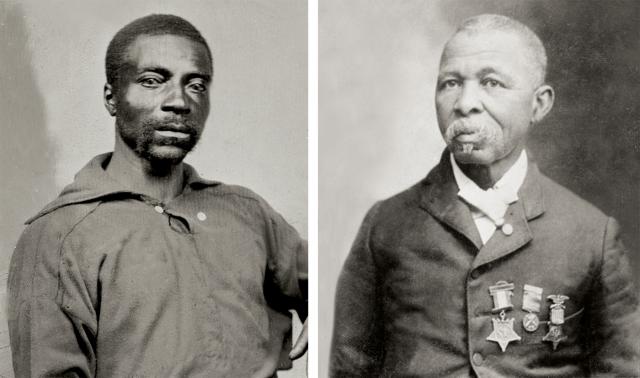

Fleeing to Freedom . . . and Joining the Fight

Not all escapees to Federal lines ended up in contraband camps. Navy policy permitted 5 percent of ship crews to be African American, but as the war progressed and demand for sailors grew, increasingly more blacks were accepted.20 On 30 April 1862, Secretary Welles issued instructions to each flag officer of the blockading squadrons:

The approach of the hot and sickly season upon the Southern coast of the United States renders it imperative that every precaution should be used by the officers commanding vessels to continue the excellent sanitary condition of their crews. The large number of persons known as ‘contrabands,’ flocking to the protection of the United States flag, affords an opportunity to provide in every department of a ship, especially for boats crews, acclimated labor. The Flag Officers are required to obtain services of these persons for the country, by enlisting them freely in the Navy, with their consent.21

Though paid much less than the $12 to landsmen and other inexperienced hands, former slaves still offered themselves for shipboard service instead of face life in the camps. In a 22 May 1862 report, for example, Lieutenant Andrew Bryson, commanding the USS Chippewa, stated: “A boat containing contrabands to the number of 18 came alongside this ship . . . 8 men, 4 women, and 6 children, 1 of the latter an infant. . . . Three of the contrabands who were willing to enter the service I have shipped [enlisted] for three years.”22

By the summer of 1862, blacks comprised 15 percent of the Navy’s enlisted ranks, with more being drawn from the abundant plantations of the Deep South. Stigmatized as “contrabands,” these enlistees stood apart from free black recruits and were assigned the most menial duties by skippers who were often reluctant to take them. But by mid-1863, with the need so acute, some support ships counted more than half the enlisted complement as African American.23 One officer glad to have such manpower available for his Mississippi Squadron was Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter, who wrote to Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox:

I take all that come. . . . I let them all know they are free . . . . What injustice to these poor people, to say that they are only fit for slaves. . . . I have shipped about four hundred able bodied contrabands and owing to the shortness of my crews, have to work them at my guns. This does not include the men on board the transports, powder vessels and store vessels.24

One can only speculate as to the fate of those who received refuge on board the Young Rover. Given Secretary Welles’ strong anti-slavery views, earlier precedents regarding runaways, the broad discretion given ship captains, an increasingly abolition-minded Congress, and the fact these particular people likely already had been delivered to the Grand Contraband Camp at Fort Monroe when the flurry of letters to the Young Rover arrived, the plaintiffs’ requests were doubtless in vain.

Ira Studley, despite inconveniencing Flag Officer Goldsborough, had become a small instrument in his nation’s evolving emancipation policy. For slave owners such as B. B. McKenney and the widow Dunton, the thin protections of the Confiscation Act soon would be gone when, on 1 January 1863, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation rendered moot the entire question of slavery in Virginia and throughout the rebelling South.

1. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion (hereinafter ONR) (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1897), series 1, vol. 5, 40–43.

2. Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W. W. Norton, 2010), 176–79.

3. Barbara Brooks Tomblin, Bluejackets and Contrabands: African Americans and the Union Navy (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2009), 5.

4. “The First Confiscation Act,” Freedmen and Southern Society Project, http://freedmen.umd.edu/conact1.htm.

5. Tomblin, Bluejackets and Contrabands, 56–57.

6. Tomblin, 11–12.

7. ONR, series 1, vol. 6, 8–9.

8. ONR, series 1, vol. 6, 10.

9. “Freedom’s Fortress,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/featured_stories_fomr.htm.

10. ONR, series 1, vol. 6, 650.

11. “Young Rover, 1861–1865,” Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/y/young-rover.html.

12. ONR, series 1, vol. 5, 40–43

13. “The First Confiscation Act.”

14. ONR, series 1, vol. 7, 229.

15. ONR, series 1, vol. 7, 409.

16. ONR, series 1, vol. 5, 40–43.

17. ONR, series 1, vol. 5, 40–41.

18. ONR, series 1, vol. 5, 42.

19. ONR, series 1, vol. 5, 42.

20. Tomblin, Bluejackets and Contrabands, 189

21. “Secretary Welles on Contrabands,” Fredonia [NY] Censor, 12 May 1862, 1.

22. Tomblin, Bluejackets and Contrabands, 193; ONR, series 1, vol. 7, 409.

23. Joseph P. Reidy, “Black Men in Navy Blue During the Civil War,” Prologue 33, no. 3 (Fall 2001), www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2001/fall/black-sailors.

24. Ari Hoogenboom, Gustavus Vasa Fox of the Union Navy: A Biography (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 199.