There is a class of explorers and a certain brand of heroism that they embody. That heroism essentially involves the type of bravery that comes not from a quick decision, but from a calculated, thoughtful decision—not only to step up to the edge of an abyss, but to drop into it. The decision may come after careful planning, test runs, and trust in technology and your team, but once the step is taken, there is no turning back. It is a moment that exemplifies having “the right stuff.”

There is also something special about undertaking a mission not for glory or accolades, but because it is an opportunity to add to human knowledge, to expand the limits not only of what is known, but also of what is possible.

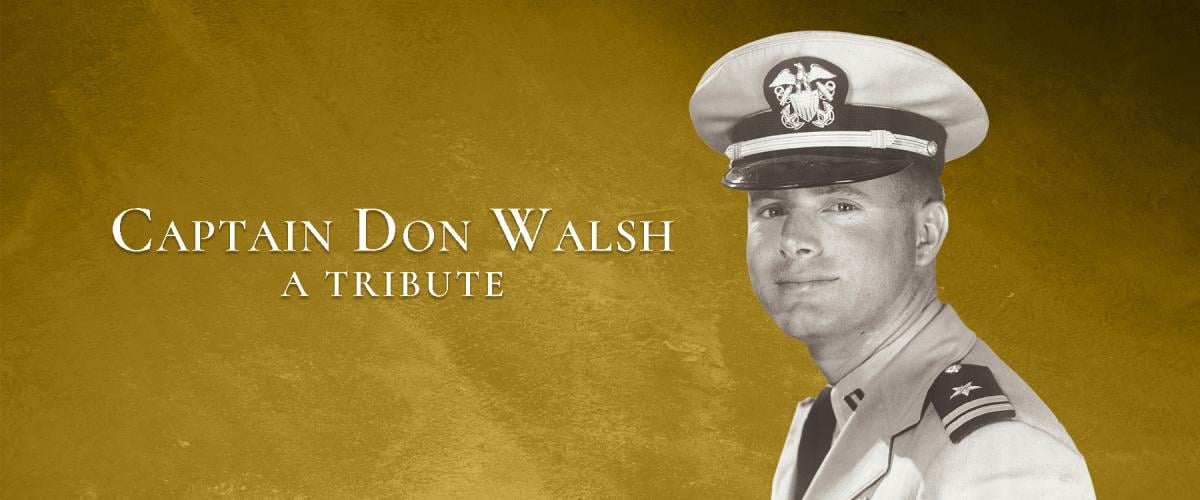

Retired U.S. Navy Captain Don Walsh, who passed away at his home in Oregon on 12 November 2023 at the age of 92, was that type of hero. He was also a hero who moved beyond his initial historic accomplishment to have a profound impact on the world of deep-sea exploration, marine science, ocean policy, and technology in a decades-long career that followed the achievement that brought him international fame.

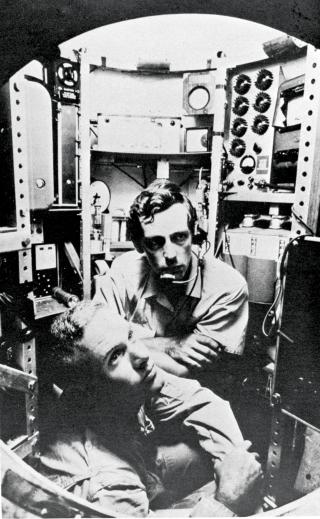

That achievement was to dive to the deepest known spot on the planet, the Challenger Deep in the Marianas Trench, on 23 January 1960. That dive, made with oceanographer and inventor Jacques Piccard in the bathyscaphe Trieste, was the culmination of Project Nekton, a classified experiment to go where no one had gone before. The immense pressure, the extreme cold, and the lengthy time it would take to fall into the depths and then rise again was daunting.

A lieutenant at the time, Walsh was a 12-year veteran who had transitioned from enlisted to officer rank after attending the U.S. Naval Academy. Pragmatically and with a hands-on approach, Walsh and Piccard basically outfitted their pioneering craft by scratch and tested it personally in a series of dives that progressed deeper and deeper.

The final dive made history. It was another example of American can-do during the Cold War—and the ocean was as much a battlefield in a Cold War as it had been in a hot war. At a time when the quest for outer space was accelerating, the Trieste dive was a major step forward in the quest for that other final frontier—the deepest depths of the World Ocean. The Trieste mission was far more than just a milestone for the record books; critical observations were made, technology was successfully tested, and Walsh and Piccard changed our knowledge of and perspectives on the abyssal depths of the planet.

The triumph of Walsh and Piccard in the Trieste opened a path that was followed by other submersibles, other missions, and other discoveries. They found undersea life in the eternal darkness of the deep, and since then, those who have been inspired to follow in the wake of the trailblazing pair have continued to discover new life in the far depths, as well as the sunken evidence of humanity’s seafaring civilizations.

What does an explorer do when he’s reached that peak, made an epic discovery, and gone where none have gone before? Captain Walsh went on to a long naval career serving in submarines, commanded the USS Bashaw (SSKS-241); earned a PhD in oceanography at Texas A&M University; created the University of Southern California’s Institute for Coastal and Marine Studies; and founded his own company, International Maritime. He served on numerous advisory boards in addition to mentoring and supporting many younger explorers, scientists, and engineers.

There is something powerful in being more than supportive when the time comes for someone else to challenge and break the record you have set. Captain Walsh showed that twice, when he supported, and was an important part of, Oscar-winning filmmaker James Cameron’s Challenger Deep mission in 2012, and again when Victor Vescovo made his 2020 mission into Challenger Deep with Captain Walsh’s son, Kelly.

I was not a close associate of Captain Walsh’s, but like many undersea explorers of my generation, I was inspired by him, occasionally interacted with him (both professionally and through the Explorers Club), respected him, and continue to seek to emulate the best of who he was and what he did. His advice and counsel to those of us at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, to the larger scientific and oceanographic community, to the submersible community, and more widely as an Ocean Elder are likely less known to readers than his 1960 achievement.

I first interacted with him as I led the team that successfully worked to save and restore Jacques Piccard’s mesoscaphe Ben Franklin (PX-15), an endeavor Captain Walsh and Piccard both agreed was important. He inspired others who work to preserve the history and artifacts of the 20th century’s bold dives into the final frontier of the planet, writing for a wide, diverse audience, including that of the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, as well as more than 200 publications with offerings ranging from book chapters to articles.

There is an innate curiosity that leads many of us to seek out what lies beyond. Captain Walsh exemplified that curiosity, which came, I suspect, with the same drive that inspires many explorers—to learn something new by going there, being there, and experiencing something different. He made additional deep-sea dives in other submersibles, piloting and observing in more than two dozen different craft, and sailed on various expedition ships. His extensive explorations with others with whom he shared his knowledge and passion included voyages to the Arctic, to Antarctica, to both poles, and to two iconic shipwrecks, the Titanic and Bismarck.

Ultimately, the statement of the Society for Underwater Technology on Captain Walsh’s passing says it best about this accomplished, heroic, and iconic man: “For those that had the honor of knowing him, he will most be recalled for his humility, kindness, and generosity. A true renaissance man and someone whose attributes we should all strive to emulate.”

Godspeed, Captain Walsh. Fair winds and following seas.

-—James P. Delgado