“This was the bitterest blow of all and people just gave up after that. Four days later there were only nine of us left.”—Tony Large

Nineteen-year-old Royal Navy Able Seaman Tony Large was involved in one of the most unusual and tragic events of World War II, often referred to as the “Laconia Incident.” His recounting of his ordeal—only four out of 51 men survived 39 days in a drifting lifeboat—has much to teach us about the mindset of survivors.

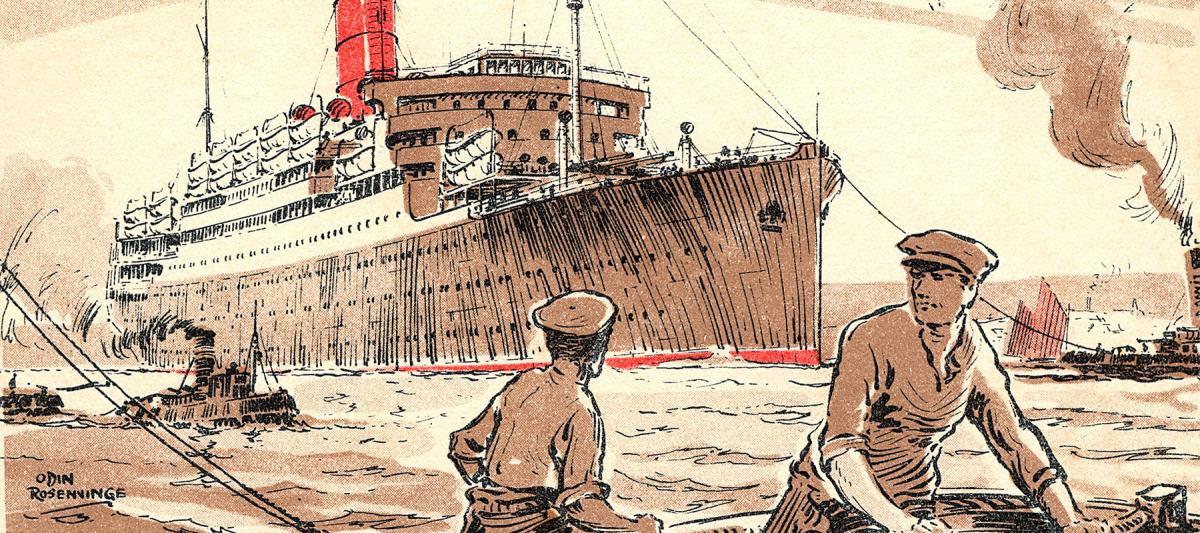

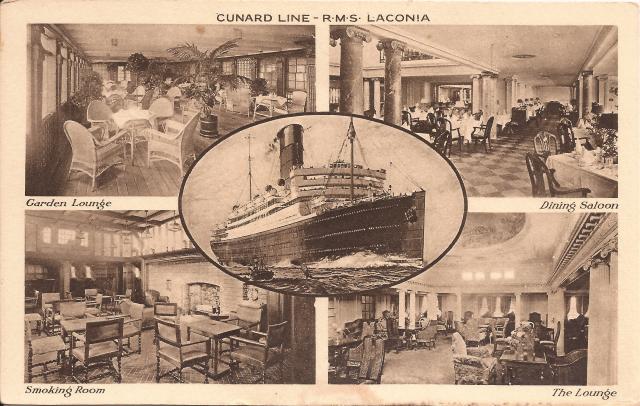

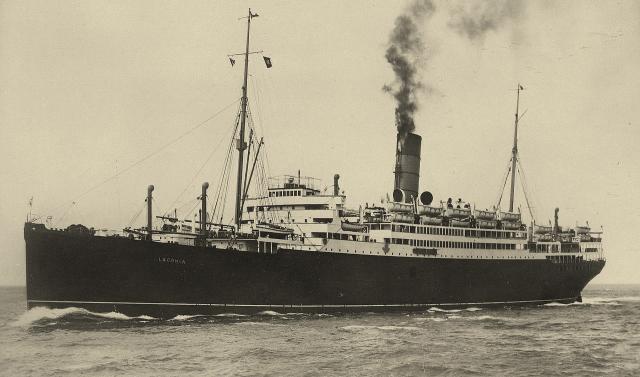

The Laconia, a British ocean liner converted to troop ship during the war, was traveling from South Africa to Plymouth, England with more than 3,000 souls on board. The passengers were a mixture of military, a few women and children, Italian prisoners of war (POWs), and their Polish guards. On 12 September 1942, the Laconia fell into the crosshairs of U-boat Commander Werner Hartenstein.

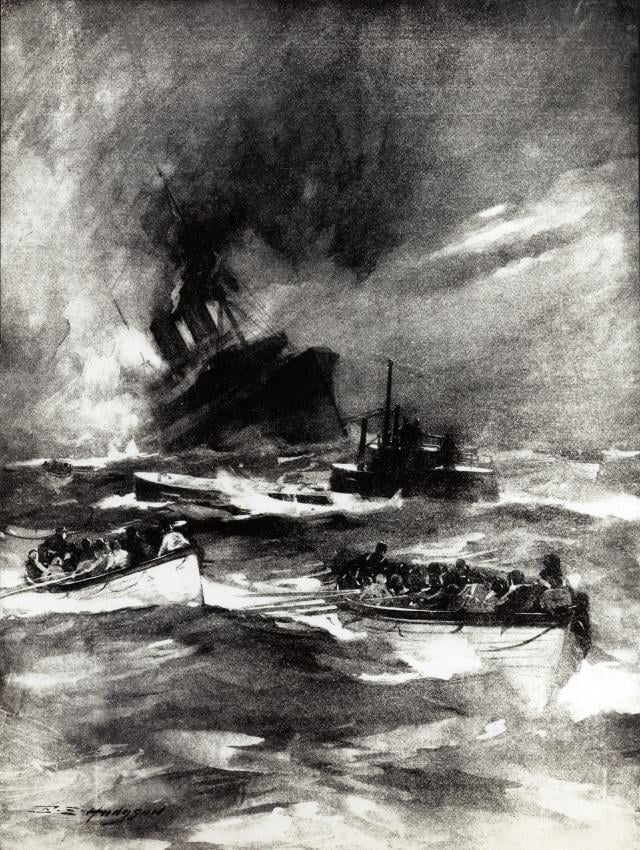

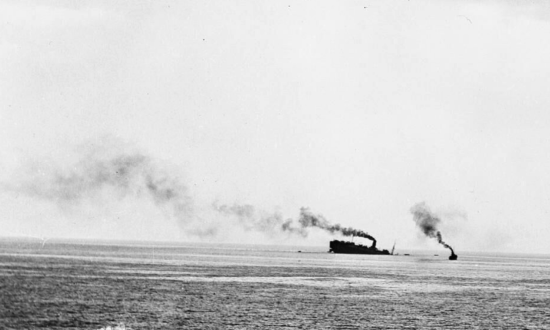

The Sinking

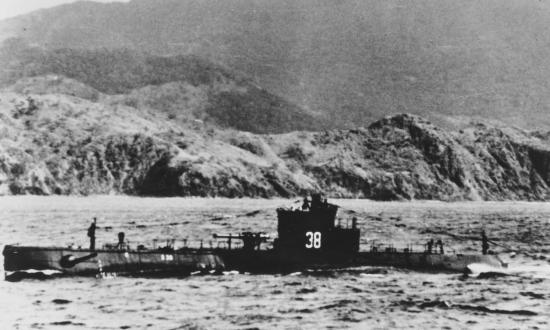

As torpedoes sank the ship, Hartenstein heard cries for help in Italian, and realized there were Italian POWs on board the ship. Wanting to rescue his allies, he asked U-boat headquarters if he could try and do so, explaining he did not have time to sort out who was Italian and who was not. He received permission to declare the area a neutral rescue operation on open radio airwaves. The commander had a large red cross painted on a white bedsheet, which was placed on the surfaced U-boat, and then he proceeded with the rescue. Aided by two other U-boats, U-507 and U-506, the Germans started retrieving survivor—regardless of nationality.

Tony Large, a young man from Great Britain, was in a lifeboat. It was one of many the U-boats gathered up on a tow line to keep them from drifting off until a ship could arrive and take the survivors on board. This was the second time Tony had been on a ship sunk during the war, the first time in December of 1941 on the HMS Cornwall.

While his lifeboat was being towed by the U-boat, an American aircraft inexplicably attacked the U-boat, even though the Americans knew a rescue of British troops and passengers was underway. One of the American bombs landed just ten feet from Tony’s lifeboat, blasting him into the water. He managed to crawl back into the lifeboat, but many others were not as fortunate and drowned or were attacked by sharks. The U-boat men cut the lines to the lifeboats, and then took the submarine beneath the sea’s surface for safety.

Adrift at Sea

Tony and 51 other men crowded into the lifeboat and spent the next 39 days adrift with little food or water. They were 700 miles from land with just three gallons of drinking water. His survival account is told in his book In Deep and Troubled Waters: The Story of a South African at War Who Survived the Sinkings of both HMS Cornwall and the Troopship Laconia in 1942 (Paul Watkins, 2001), and in a letter he wrote to his parents four days after his rescue. The survivors, he explained, occasionally caught fish using a bent nail as a hook. Their thirst was so great they drank the blood from the fish and sucked on the eyeballs for moisture. For some, the lack of water was too much to overcome. Several castaways gave into the temptation to sip sea water. Tony and 29 others resisted the urge and were alive on day 17.

When I read the book and Tony’s letter the incident that occurred on day 17 really captured my attention. It involved a freighter that passed just 300 yards from the lifeboat. “We could not believe her lookouts would fail to see us, or fail to hear our screams and our yells . . .” But that is exactly what happened. “This was the bitterest blow of all and people just gave up after that. Four days later there were only nine of us left.” He recounted that the despair was just too much for many of the survivors, that their expectations to be rescued by the ship—only to have it steam right past them—prompted many to start drinking sea water. Talking about a friend and fellow survivor, Tony wrote, “I was not observant enough, or trained enough, to calculate the depths of his misery or his sense of hopelessness after the unhappy passage of the north-bound cargo ship.” His friend calmly climbed over the side of the lifeboat and paddled away to his death. Such was the effect of the near-rescue.

Perhaps Tony endured because of his prior brush with death at, and he knew that help could come at any time if he fought on as long as he can. Those people that gave up only needed to hang on three more days—that was when it rained, and the life-giving moisture kept Tony and three others alive for a few more days. Despite the rain, five of the nine people still alive died from their weakened condition.

Rescue

On the 39th day, Tony and another survivor saw another ship approaching. It would turn out the be the St. Wistan, an escort ship protecting a convoy. The two remaining survivors were asleep. “We didn’t dare wake the two sleeping forward because of the general depression it would cause if the ship did pass us by,” he recalled. Only when Tony was sure the sailors on the ship had seen him did he wake the men. The two castaways who had been asleep would not sit up or even bother to look, but instead said “Don’t joke about things like that.”

But this was not a cruel joke. All four survivors were saved, having drifted over 600 miles. In Tony’s letter to his parents, he said the thing that kept him going was “the thought that after you two had sacrificed and done so much to bring me up and launch me, I should waste your efforts by drinking salt water or taking a walk [suicide].”

Like many of survivors, Tony attributed fighting to live for loved ones as a reason to carry on. Equally important, however, is that Tony had learned from his prior experience adrift at sea that salvation comes on its own time, and the job of the survivor is to wait it out.

Tony had learned not to put a time limit on salvation, but rather keep fighting until it came. He never stopped believing rescue was possible but did not pin all his hopes on a specific time frame for it to happen. For the rest of us, when faced with adversity or striving toward a difficult goal, the trick is to stay as even-keeled as possible, despite setbacks and delays. Although near-misses can feel crushing, keep the hope that the next chance at rescue—or reaching your goal—is coming.