Among the first officers of the Revenue Cutter Service is a captain who fought with Paul Revere, worked closely with General Benjamin Lincoln, and sailed with Captain John Barry, one of the fathers of the U.S. Navy. He was even considered for command of the famous USS Constitution before Samuel Nicholson was chosen to be Old Ironsides’ first captain. Despite this, the name of Captain John Foster Williams is little known today. In many ways, Williams formed a cornerstone upon which the new Revenue Cutter Service was built.

Today, the Coast Guard recognizes Hopley Yeaton as its first commissioned officer. However, while all the captains of the original ten cutters were commissioned early to oversee the construction of their vessels, Williams deserves special recognition; records indicate he was likely the first officer to get underway. Of the ten original cutters, the USRC Massachusetts, under Williams’ command, was probably the first one operational. He truly is one of the fathers of the Coast Guard.

Captain Williams

Williams was born in Boston’s North End on 12 October 1743. He first went to sea at the age of 15, and within a decade was in command of merchant ships. In 1769, his vessel was heavily damaged and dismasted. Rescue did not come for six weeks, and by that point, Williams was the only survivor.

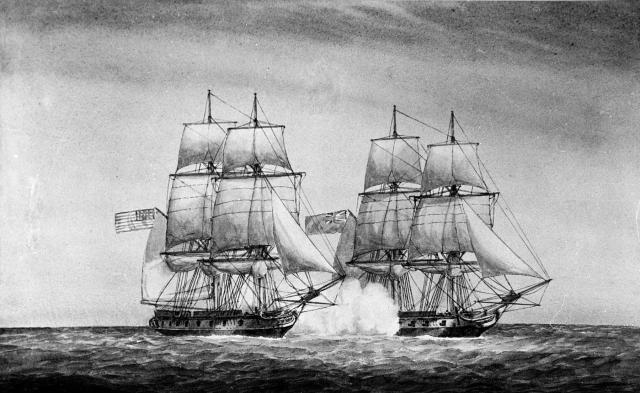

On 14 May 1776, prior even to the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Williams entered service in the Massachusetts State Navy (a distinctly separate entity from the Continental Navy) and was given command of the sloop Republic. He commanded the Republic until December 1776, when he was given command of a larger vessel, the brig Massachusetts. At some point in 1778, he took command of the brig Hazard, and it was while in command of her that he joined the British privateer Active, 18 guns, in battle. Under Williams’ command, the Hazard defeated and captured the Active and took her as a prize back to Boston, winning him and his crew much acclaim.

Several months later, Williams and the Active were assigned to the disastrous Penobscot Expedition in Maine, under the command of Commodore Dudley Saltonstall. It was during this expedition that Williams fought alongside Paul Revere, who served as a colonel during the ill-fated undertaking. The expedition was intended to drive British forces to leave the coast of Maine and consisted of a mix of vessels from the Continental Navy, Massachusetts State Navy, and privateers, totaling 44 ships in all. Poor leadership, lack of aggressiveness, and indecision on Saltonstall’s part led to the American forces being trapped in Penobscot Bay after the arrival of a superior British naval force. Rather than face certain death or capture, Williams and the other leaders decided to destroy their vessels and head inland. Williams had to feel a deep sense of regret as he ordered the destruction of his vessel. The Hazard had been the scene and instrument of his first and (to that point) greatest naval victory. After burning their ships, and with little food or ammunition, the survivors of the expedition began a grueling 200-mile trek through the wilderness to return to Boston. By the time they made it, the Patriots had lost 470 men, and the British just 13. All 44 of the American ships had been destroyed, sunk, or captured by the British. It was the worst American naval defeat until Pearl Harbor, 162 years later.

In the aftermath of the Penobscot Expedition, there was much investigation into the causes of the defeat and the conduct of the Patriot leadership. Many officers were accused of cowardice and ineptitude. Through all the discussion that followed, Captain Williams’ conduct and leadership marked a bright spot in an otherwise dark point in the American Revolution. He was one of few leaders to make it through the incident with his reputation intact. As a result, he was entrusted once again by the Massachusetts State Navy with a command, this time with the force’s newest and largest vessel: the Protector, boasting 26 guns.

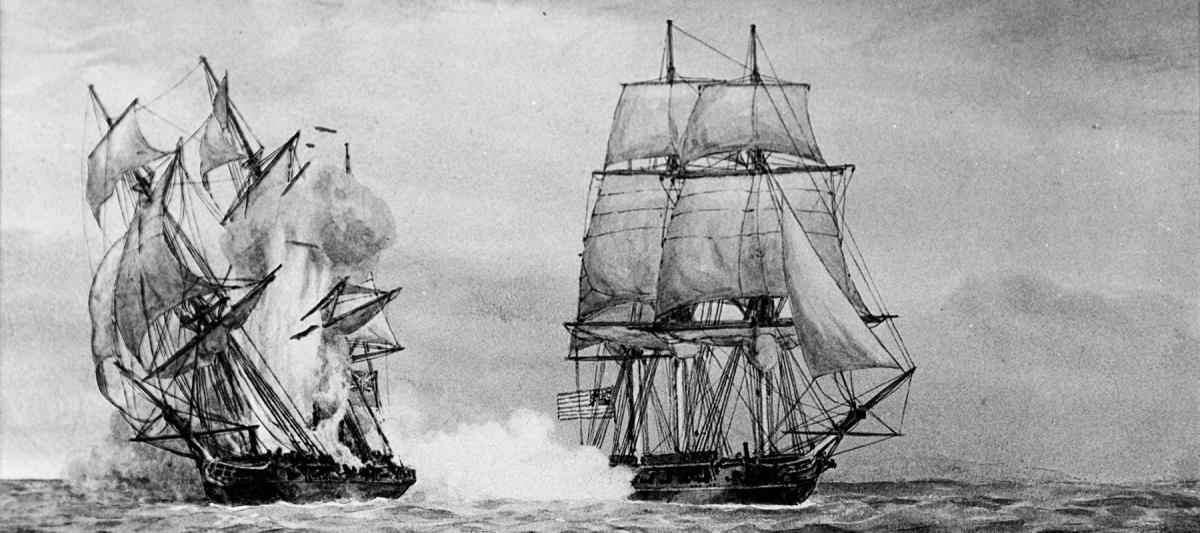

Captain Williams and his crew wasted no time, engaging and sinking the larger, 32-gun Admiral Duff on 9 June 1780 after three hours of battle. During this battle, Williams was standing on the deck of the Protector when a chunk of shrapnel from an enemy cannon blew the metal speaking trumpet he was using to give orders out of his hand. Williams reached down, picked it up, and resumed giving his commands without so much as flinching or breaking stride.

Capture by the British

With multiple victories to his name, Captain Williams was now wanted dead or alive by the British government. In May 1781, the Protector was cornered by HMS Roebuck and Medea. Seeing that he could not win or escape, Williams surrendered his vessel. With his crew imprisoned on the infamous hulk Jersey in New York Harbor, he was informed that the British did not recognize him as a legitimate enemy officer due to his commission from the State of Massachusetts, and he and his men would not be exchanged. Williams and two of his officers were jailed in London but managed to escape and make their way across the English Channel to France, catching a ride home on the Continental Navy frigate Alliance, commanded by Captain John Barry. Making landfall at New London, Connecticut, Williams returned to Boston. By January 1783 he had taken command of the privateer Alexander and returned to sea. By the end of the war, due to his impressive career in the Massachusetts State Navy, Williams had become something of a folk hero for the people of Boston. In a 1788 parade that celebrated the adoption of the Constitution, Williams and his old crewmates “sailed” a float built in the form of the old Protector through the streets. The scene was captured by locals in the words of a song sung to “Yankee Doodle:”

“John Foster Williams, in a ship

Joined with a social band, sir,

And made the lasses dance and skip

To see him sail on land, sir.”

The war had made him one of Boston’s most famous sons and one of the most well-known naval officers in the nation.

After the Revolution

After the Revolution, Williams resumed his career as a merchant captain and remained in this line of work until 1790. His reputation from the Revolution, and an endorsement from General Benjamin Lincoln, led Alexander Hamilton to recommend to President George Washington that Williams be commissioned into the new Revenue Cutter Service and given a command of one of the new ships. He was appointed by President Washington to be the master of the yet to be built Massachusetts, homeported in Boston.

The original ten cutters were not large vessels. All would be considered small boats and not cutters by the criteria of today’s Coast Guard. Williams and the other officers assigned to the Massachusetts argued that the diminutive design proposed for the vessel was not adequate for the seas in which she would operate. Their arguments convinced Hamilton, and the Massachusetts would be the largest of the original revenue cutters. The ship was built at Newburyport, Massachusetts. No contemporary painting or drawing of the vessel has ever been located, but the cutter was said to be 60 feet long, weigh about 70 tons, and was schooner rigged, likely with six light swivel guns as her armament.

Captain Williams took the Massachusetts to sea for the first time in 1791, and he cruised the New England coast enforcing the nation’s customs, duties, and revenue laws. For a time, he and the Massachusetts cruised with the cutter Scammel, captained by the first Revenue Cutter Service Officer, Hopley Yeaton. It was on board the Massachusetts in 1792 that Captain Williams began to experiment with desalinating water. Using a system of kettles and piping, Williams claimed to have been able to distill fresh water from seawater. He reported his findings in a 1792 edition of Massachusetts Magazine, describing his invention and saying, “I then put 5 gallons of salt water in an iron pot, made the pot lid tight by putting some old canvas round it . . . I got from it 2 quarts of good fresh water in one hour and a half.”

The original Massachusetts proved to be a slow vessel and expensive to operate, so she was sold in late 1792, and replaced with the smaller Massachusetts II, with Williams again serving as master. In 1798, Williams was considered for command of both the newly formed U.S. Navy’s frigate Constitution, and the Revenue Cutter Service’s larger, newer vessel Pickering, but was passed over for both, potentially due to his age and political positions—he was a noted and apparently vocal Anti-Federalist during a Federalist administration. He continued to serve, commanding the Massachusetts III during the War of 1812 and surviving through that conflict’s conclusion.

Legacy

On 24 June 1814, at the age of 70, Captain John Foster Williams passed away in Boston. He had served in the Revenue Cutter Service for 24 years and died while still in command of the Massachusetts III. He was interred at the Granary Burying Ground, along with other heroes of the Revolution, including Samuel Adams, Crispus Attucks, and Paul Revere. Today, the entrance to Coast Guard Base Boston faces John Foster Williams Square on Commercial Street, and the headquarters of the First Coast Guard District is located at the Captain John Foster Williams Building. These serve as fitting tributes to one of Boston’s greatest Coast Guard heroes. Alexander Hamilton is rightly considered to be the “Father of the Coast Guard,” just as the U.S. Navy considers John Adams to be a “Father of the Navy,” but the Navy also recognizes two others, Captains John Paul Jones and John Barry, as sharing that title with Adams. It is time for John Foster Williams to be considered a “Father of the Coast Guard” alongside Alexander Hamilton.