In April 1912, the Royal Mail Ship Titanic struck an iceberg and sank in the North Atlantic. The accidental sinking of this “unsinkable” passenger liner and the consequent loss of life shocked the public on both sides of the Atlantic, initiating the 1913 Safety of Life at Sea Convention in England and establishment of the International Ice Patrol. Originally supported by the U.S. Navy, this patrol tracked icebergs and reported their location to ships in the North Atlantic. Soon after the patrol’s establishment, the Navy could no longer spare warships, so the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, a Coast Guard ancestor service, assumed the duty.

Prior to World War I, President William H. Taft’s administration proposed dismantling the Revenue Cutter Service and distributing its assets and missions among the Navy and other federal agencies. But when war erupted in Europe in 1914, U.S. political leaders had to scrap this plan.

The outbreak of World War I saw the responsibilities of revenue cutters grow exponentially. As the conflict spread to other parts of the globe, President Woodrow Wilson decided to retain the Revenue Cutter Service as an armed sea service with the thought that, when combined with the U.S. Life-Saving Service, the assets and personnel of the two agencies would prove effective in guarding the nation’s shores both by land and at sea. On 28 January 1915, Wilson signed the Act to Create the Coast Guard, combining both services into one military agency, establishing the U.S. Coast Guard to serve as a branch of the Navy during conflicts.

On 6 April 1917, Congress declared war on Germany. That same day, the U.S. Navy’s communications center in Arlington, Virginia, transmitted the code words “Plan One, Acknowledge” to Coast Guard cutters, units, and bases throughout the United States. This coded message initiated the service’s transfer from the Treasury Department to the Navy, placing the service on a wartime footing.

The details behind Plan One were developed in secret. In March 1917, in anticipation of the declaration of war, Coast Guard Commandant Ellsworth P. Bertholf had issued a confidential booklet that laid out the plan and the assignments of cutters to various naval districts. When the U.S. declared war, Bertholf authorized an “ALCUT” (all cutters) message, a coded dispatch transmitted by radio and telegraph to every Coast Guard cutter and shore station.

With the Plan One dispatch, nearly 50 cutters, hundreds of small craft, and 280 shore installations came under Navy control and joined the fight. The Treasury Department transferred officers and enlisted men, cutters, and units to the operational control of the Navy Department. The service augmented the Navy with 223 commissioned officers and 4,500 enlisted personnel, including the first women to don Coast Guard uniforms and the first significant number of minority Coast Guardsmen to serve.

The Port Security Mission

One of the service’s first important wartime missions was port security, which had a long history with the Coast Guard. In the 1800s, the Revenue Cutter Service had been tasked with the movement and anchorage of vessels in U.S. waters. In 1915, the modern Coast Guard adopted the mission when the service was directed by the Rivers and Harbors Act “to establish anchorage grounds for vessels in all harbors, rivers, bays and other navigable waters of the United States.” With the war in Europe, protecting U.S. ports became a matter of national security.

During the war, the tremendous increase in munitions shipments required increased manpower and assets to oversee this vital mission. An explosion at the munitions terminal on Black Tom Island, New Jersey, rocked New York City on 31 July 1916. The terminal was a primary staging area for ordnance shipped to the war in Europe. Set off by German saboteurs, the blast shattered windows as far away as Manhattan, killing several people and causing property damage amounting to approximately $1 billion in present-day currency. The explosion was 30 times more powerful than the 2001 World Trade Center collapse and ranks as the worst terrorist attack on U.S. soil prior to 11 September 2001. This disaster quickly focused attention on the dangers of storing, loading, and shipping volatile explosives near major U.S. population centers.

The Coast Guard’s port security duties expanded rapidly as a result of the war effort. Passed in June 1917, the Espionage Act shifted responsibility for safety and movement of vessels in U.S. harbors from the Army Corps of Engineers to the Department of the Treasury. The Coast Guard was assigned to protect merchant shipping from sabotage, safeguard waterfront property, supervise vessel movements, establish anchorages and restricted areas, and regulate the loading and shipment of hazardous cargoes. The act also gave the Coast Guard the right to control and remove passengers from ships, allowing the service to assist in arresting foreign merchant seamen on board merchant vessels of combatant nations interned in U.S. ports.

Coast Guard officers became instrumental in port security during the war. Captain Godfrey Carden earned the nickname “captain of the port” for his role as overseer of New York’s port security; he commanded nearly 1,500 officers, four tugs borrowed from the Navy and the Army, five harbor cutters, and an assortment of small craft. In all, his division was the service’s largest wartime command. The crews in New York embarked more weapons and war material than any other U.S. port. In the span of one and a half years, Carden’s men oversaw the loading of 1,700 ships with more than 345 million tons of shells, smokeless powder, dynamite, ammunition and other explosives. The Coast Guard later established captain-of-the-port offices in Philadelphia; Hampton Roads, Virginia; and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

Coast Guard officers held other important commands during World War I. Twenty-four commanded naval warships in the war zone, five commanded warships attached to the American Patrol detachment in the Caribbean, 23 commanded warships attached to naval districts, and five Coast Guard officers commanded large training camps. Shortly after the war’s armistice, four Coast Guard officers also were assigned to command large naval transports engaged in bringing the troops home from France. Officers not assigned to command served in practically every phase of naval activity, including on board transports, cruisers, cutters, and patrol vessels; in naval districts; as inspectors; and at training camps. Of the 223 Coast Guard officers who served, seven met their deaths as a result of enemy action.

At home, the war required vigilance on the part of Coast Guard stations. For example, on 16 August 1918, the British steamship Mirlo struck a mine laid by a U-boat off the North Carolina coast. Her cargo of gasoline and refined oil spread over the sea and ignited. Chief Boatswain John Midgett and the Chicamacomico Coast Guard Station crew launched their motor surfboat and forced their way into this mass of fire and wreckage to rescue six men clinging to a capsized lifeboat. Midgett and his men fought the intense heat to pick up two more boatloads of men, landing them ashore safely through heavy surf. Altogether, the Chicamacomico boat crew saved 42 people and was awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal.

Service Overseas and Abroad

The Coast Guard was not limited to domestic duties during the war, and soon vessels and personnel were called to serve overseas. In August and September 1917, six Coast Guard cutters—the Ossipee, Seneca, Yamacraw, Algonquin, Manning, and Tampa—joined U.S. naval forces in European waters. Based at Gibraltar, they constituted Squadron 2, Division 6, of the patrol forces for the Navy’s Atlantic Fleet. The cutters escorted hundreds of vessels through the submarine-infested waters between Gibraltar and the British Isles and performed patrol and escort duties in the Mediterranean. Several large cutters performed patrol and convoy escort duties in U.S. coastal waters, off Bermuda, in the Azores, in the Caribbean, and off the coast of Nova Scotia, operating under the orders of either naval district commandants or the Chief of Naval Operations.

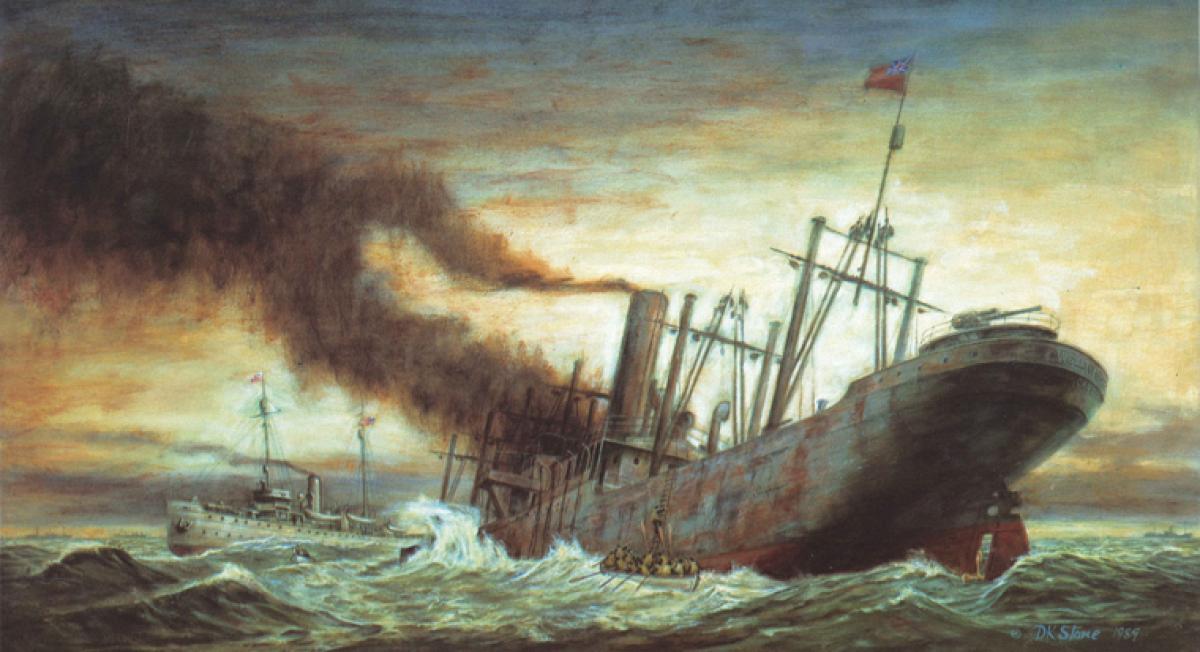

In addition to escort duty, cutters continued to perform their traditional missions. At 0245 on 25 March 1918, the British naval sloop Cowslip steamed out of Gibraltar to meet a convoy escorted by the Seneca. The Cowslip was struck and almost broken in two by a torpedo from one of three German submarines bound for the Mediterranean. Warned to stay away because of the presence of U-boats, the Seneca followed the laws of her service and three times stopped to send off small boats to take on survivors, eventually saving two officers and 79 enlisted men. In late June of the same year, the Seneca saved 27 crew members of the torpedoed British merchant steamer Queen. And when the British steamer Wellington was torpedoed in mid-September, a volunteer crew from the Seneca attempted to save the vessel. The ship finally foundered on 17 September, and 11 Coast Guardsmen lost their lives trying to save her. In all, 20 of Seneca’s boarding party received the Navy Cross, and one received the Distinguished Service Medal, making this event the most honored combat-related operation in service history.

Wartime Coast Guard aviators were active in the expanding Naval Aviation force, with many senior in rank to their Navy counterparts. Eight Coast Guardsmen had earned their wings by the onset of the war, and six were assigned as commanding officers of major commands. Coast Guard lieutenants became commanding officers of the naval air stations at Ille Tudy, France; Chatham, Massachusetts; Sydney, Nova Scotia; Key West, Florida; and the enlisted flight training school at Pensacola, Florida.

During the late spring and summer of 1918, the German Navy stepped up submarine attacks on shipping off the U.S. East Coast. On 21 July, a U-boat surfaced and began firing her deck guns at a tugboat and three barges off Cape Cod. The sub was attacked by two seaplanes from Naval Air Station Chatham, where Lieutenant Phillip Eaton was in command. Eaton, who regularly flew patrols, made his approach and dropped two bombs. One landed on the submarine and the other landed close to her hull. Unfortunately, neither bomb exploded and the U-boat submerged and escaped. However, Eaton did prevent the sinking of the tug and any loss of life and concluded the first naval aerial attack in the Western Hemisphere.

Baptism of Fire

World War I served as a baptism of fire for the Coast Guard. During the war’s nearly 19 months, the service would lose five ships and nearly 200 men. These vessels included two combat losses. On 6 August 1918, U-140 sank the Diamond Shoals Lightship after her crew transmitted to shore the location of the marauding enemy submarine, but no lives were lost. On 26 September 1918, after escorting a convoy from Gibraltar to the United Kingdom, the cutter Tampa was torpedoed by UB-91. The cutter quickly sank, with the loss of all 131 persons on board, including four U.S. Navy men, 16 Royal Navy personnel, and 111 Coast Guard officers and men. It proved to be the United States’ greatest naval loss of life from combat.

Altogether, more than 8,800 men and women served in the Coast Guard during the war. The service’s heroes received two Distinguished Service Medals, eight Gold Lifesaving Medals, almost a dozen foreign honors, and nearly 50 Navy Crosses. In 1919, control of the Coast Guard was returned once again to the U.S. Treasury Department.

By the war’s end, the Coast Guard’s wartime assignments had become a permanent part of the service’s defense readiness mission. This baptism of fire cemented the service’s place among U.S. military agencies and prepared it for the challenges ahead during Prohibition’s Rum War and in World War II, and also cemented the service as the nation’s first defense in shore patrol and marine safety.

Sources:

Donald L. Canney, U.S. Coast Guard and Revenue Cutters, 1790 - 1935 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1995).

Julian S. Corbett and Henry Newboldt, History of the Great War: Naval Operations. 5 vols. (London: Longmans, Green and Co., (1920 - 31)).

Charles E. Johnson and Richard O. Crisp, A History of the Coast Guard in the World War. 4 vols. Unpublished typescript.

Robert Erwin Johnson, Guardians of the Sea: History of the United States Coast Guard, 1915 to the Present (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1987).

Alex R. Larzelere, The Coast Guard in World War I (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2003).

Alex R. Larzelere, “United States Coast Guard Roll of Honor,” 6 April 1917 to 30 November 1918 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1919).

National Archives. Handbook of Federal World War Agencies and Their Records, 1917-1921 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1943).