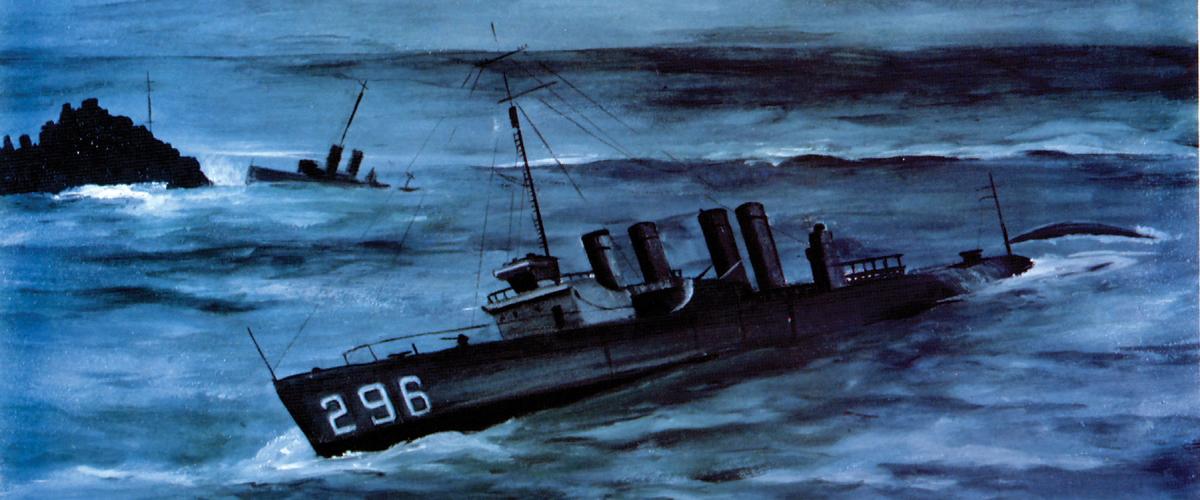

This year marks the centennial of the U.S. Navy’s greatest peacetime disaster—a destroyer squadron’s deadly wreck at Honda Point on the California coast, today part of Vandenberg Air Force Base. The disaster has left a graphic reminder: At low tide, some of the wreckage can still be seen on that rugged and treacherous stretch. The tragedy also has left an enduring wake of controversy and mystery, with many still wondering how a professional navy could have made such a horrific mistake.

The disaster has spawned countless newspaper and magazine articles and at least six books, including a 1960 naval classic, Charles A. Lockwood and Hans Christian Adamson’s Tragedy at Honda. All that attention, understandably, has focused on the groundings of the ships themselves and the ensuing judicial proceedings, with relatively little scrutiny of one key player: Secretary of the Navy Edwin Denby.

A close look at Denby reveals a man in professional and personal turmoil, vexed by the official U.S. Navy investigation of the disaster and apparently intent on fixing blame. But why?

‘Incomprehensible’

Shortly after 2100 on 8 September 1923, nine Clemson-class destroyers of Destroyer Squadron (DesRon) 11 racing in column formation sailed into dense fog surrounding Point Honda, a stretch of jagged, partially submerged volcanic rock near Santa Barbara known among mariners as “the Devil’s Jaw.” Seven ships subsequently wrecked, following one another blindly, either grounding on the rocks or colliding with one another. Most tragically, 23 sailors died.

The ensuing court of inquiry, led by future Chief of Naval Operations then-Rear Admiral William Veazie Pratt, found the squadron leaders primarily responsible through faulty navigation, including the disregarding of new state-of-the-art radio direction bearing reports. Further, the admiral found the division leaders and individual destroyer captains responsible to a lesser degree for blindly adhering to unwritten “follow the leader” destroyer doctrine, much like aircraft in formation completely trusting their lead aircraft. The inquiry bound over 11 officers for trial, the single largest group court-martial in U.S. naval history.

The court convicted the squadron commodore and flagship captain of culpable inefficiency in the performance of duty and, through negligence, suffering naval vessels lost, run onto the rocks of Point Honda. The court convicted one destroyer captain of negligence in performance of duty, a verdict that was promptly overturned by the commander of the U.S. Fleet. The court acquitted all the other defendants.

The day after the groundings, Secretary Denby called the disaster “incomprehensible.” Denby’s initial remarks, which usually would be held in abeyance by Secretariat protocols until the investigation was completed, immediately suggested fault among the DesRon 11 officers. Public sentiment, however, already was emerging that the officers were victims of nature and circumstance rather than their own negligence. Two days after the groundings, The New York Times ran a front-page story headlined: “Garbled Wireless, Fog and Currents Doomed Destroyers.”

A reporter asked Denby, “Do you consider a speed of 20 knots in a fog justified?” Denby replied: “Not unless there was some peculiar circumstance.” Denby apparently did not know that 20 knots had been authorized for the run, and that the squadron had been testing its turbines long-distance. The squadron also was attempting by fleet directive to set a speed record, at least partly to justify the squadron’s existence amid post–World War I reductions. Denby, overseeing the drawdown of the Navy’s fleet following the war, already had ordered 150 destroyers and 92 other ships out of commission.

A 47-Year-Old, 254-pound Marine Recruit

Denby brought a colorful background to the post of Navy Secretary and the ensuing Honda fiasco. Originally from Evansville, Indiana, he had moved to Peking at age 15 when his father was appointed Minister to China. Nine years later, he returned to the United States, enrolled at University of Michigan law school and played center for the Wolverines football team. At the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, Denby abandoned his law practice to enlist in the Navy, serving as a gunner’s mate in the auxiliary cruiser Yosemite, which participated in the blockade of Havana.

Returning from Cuba and the “Splendid Little War,” Denby settled in Detroit, married at 41, and had two children. He also began investing in Detroit’s nascent automobile industry and cofounded the Denby Motor Truck Company. An amateur comedian and poet, he served in the Michigan statehouse, then served three terms in Congress until he was defeated for re-election in 1910. When World War I broke out, Denby enlisted once again, but this time in the Marines. He was then 47 years old and an obese 254 pounds. “I knew I was getting so damn fat it was going to kill me,” he later joked. “This going wasn’t a heroic deed, it was heroic treatment.”

His physician warned him that he might not survive Marine boot camp. But Denby pulled all the strings he could find to get age and weight waivers, eschewing a commission, saying, “I’ll work my way up from the bottom.” And he did, enlisting as a private and rising through the ranks to leave at war’s end a major.

Denby seemed to harbor some resentment toward naval officers, or at least toward those like the U.S. Naval Academy graduates involved in the Honda Point disaster, who he apparently felt were privileged. Denby said of his World War I service: “Why did I enlist in the ranks? Because some must. All cannot begin as officers.” He told a reporter, “All the young fellows are pulling wires to be sent to training camps or land commissions by other ways. I am going to enlist as a private and I’m going to pull wires to accomplish that.” After the war, he preferred to be addressed as “Major Denby,” even in newspaper headlines.

Denby had been running Detroit’s probation department in February 1921 when newly elected President Warren G. Harding tapped him to be the 42nd Secretary of the Navy. This was Harding’s final cabinet pick and a surprise move that the press called a “fairy tale ending” to Denby’s military career. Alas, Denby’s ending would prove more a nightmare for him, personally and professionally.

Denby assumed office and promptly announced he would go to sea whenever possible to understand the administration of the fleet. He earned a moniker as a “sea-going secretary” and fed a narrative that, as a former Michigan governor put it, Denby was “simply a big boy that had not fully matured.”

Teapot Dome and Other Headaches

By the time of his appointment as Navy Secretary, Denby had regained the weight he’d lost during World War I and then some. An early news report described him as “a huge man with a dome-like head bare of hair except for a fringe at the level of his ears. . . who smiled happily.” Later, as scandal swirled around him, descriptions grew darker. A wire service wrote soon after the Honda tragedy, “Edwin Denby, secretary of the navy, is a large, fat, good natured person who ordinarily exhibits a shining bald head and a bland smile to all visitors—but there are times when it is hard for him to smile and the [dome] shows corrugated wrinkles of worry.”

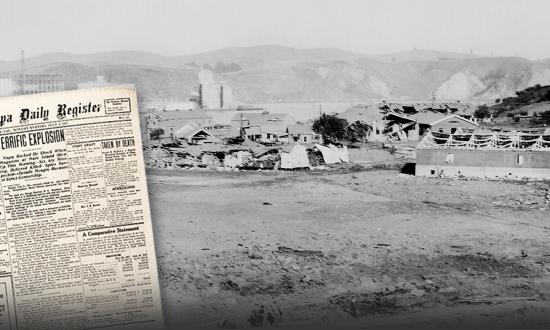

By the time the Honda Point disaster struck, Denby already had much about which to worry. He was at the center of a blossoming scandal over leasing of naval oil reserves at Teapot Dome, Wyoming. Albert Fall, then Interior Secretary, had convinced Denby that the Department of the Interior could better oversee naval oil fields than could the Navy Department. Denby, at Fall’s urging, had secured President Harding’s endorsement to transfer control of the oil to the Interior Department from the Navy Department. Fall quickly arranged to lease the reserves to oilmen with whom he had business interests and convinced Denby to sign the leases.

Now the oilmen were drilling and profiteering, and the Senate had launched an investigation by special committee. Fall, in turn, resigned, accused of taking kickbacks of more than $400,000 in personal loans, leaving Denby in the crosshairs. He proclaimed his innocence, publicly and privately, and cast himself as a victim, the victim. Denby wrote in a memo, “I had been absolutely left alone to stand the abuse that was being heaped upon me . . .” He wrote to a prominent banker, “Politics is back of most of the charges that have been made and some of us have had to suffer on account of it.”

Denby also was taking intense fire for sinking conditions within the Navy Department: Poor morale, heavy desertions, steady officer resignations, and a string of disasters now were topped by the Point Honda groundings. Denby’s credibility with Congress already had suffered over his earlier request that year for a special supplemental authorization for the department after the Washington Naval Treaty had set draconian limits on fleet sizes. He argued that the Navy needed the funds partly because the British had altered their battleship turrets to allow long-range firing.

It turned out the Royal Navy had made those alterations before the Washington Naval Conference and not afterward, as Denby had implied. The British government was threatening to lodge a formal protest.

To make matters worse, just one month before the Honda tragedy, in August 1923, Denby’s patron President Harding had died unexpectedly in office. Harding’s successor, Calvin Coolidge, had kept Denby on, refusing to accept his pro forma customary resignation. But Coolidge’s move didn’t necessary signal great confidence; the new President Coolidge had kept nearly all of Harding’s senior staff, including his personal physician (even after the President had died mysteriously).

To add to his professional problems, Denby apparently had serious health concerns of his own. The day before Harding died, Assistant Navy Secretary Theodore Roosevelt Jr. sent Denby a “Dear Ned” letter noting Harding’s “dangerous condition,” partly as a warning that Denby should take TR Jr.’s advice of six weeks of rest. “I have been fearful all along that you would get run down and some slight turn of this sort would come which would be very serious on account of your condition.”

To add to his worries, Denby also was facing personal financial turmoil, prompting his money manager to send him a “depressing” statement showing “quite an apparent depletion of your assets.” The money man warned that Denby had used his wife’s Hupp Motor Car Company holdings as collateral in his own loans, and if Hupp’s stock dropped further, Denby would have to repay the loans with funds he did not possess, which “might cause us some embarrassment.”

All these travails suggest perhaps why Denby’s dome might have already sprouted worry wrinkles when DesRon 11 crashed into the rocks—and why Denby might have seen the Honda debacle as a chance to deflect attention from his own troubles.

‘Mysterious Circumstances’

Denby let it be known that he was upset at getting little information about Honda out of the uniformed Navy in the first days following the wrecks as he faced a ravenous press. “Unable to explain either the delay in the receipt of official reports and explanations or the reasons for such an unprecedented disaster, officials of the navy, from Secretary Denby down, appeared in a state of astonishment,” the Baltimore Sun wrote on page one. “It is plain that high navy officials have been embarrassed. . . .”

The Sun then cataloged Denby’s ignorance: “Secretary Denby had received practically no information from California. He had neither a list of the victims nor a statement of how and why seven destroyers piled up one after another on the California coast.”

Denby was irked further when reports emerged that two more destroyers were damaged at Honda than the seven initially reported. These last two ships had been able to extricate themselves from Honda’s rocks through superior seamanship, escaping on their own power and remaining, unlike the others, salvageable.

Denby told the press that, for some inexplicable reason, reports on the additional two damaged destroyers were sent directly to the Naval Board of Inspection and Survey instead of through the Division of Communication. In the heat of the moment this played like bureaucratic “gobbledygook.”

Denby ordered a full inquiry into the Honda disaster to be held in public so that, he said, those responsible would be fully exposed in the press. The inquiry would determine not only guilt, but why information was withheld for six days from Navy headquarters, in violation of official Navy procedure, and then erroneously sent to the wrong naval bureau.

He issued a news release: “I have ordered that the fullest publicity be given to the investigation to be conducted by the Court of Inquiry. This is a very unusual course, and one entirely contrary to custom. But I have taken this step because of the mysterious circumstances surrounding the wreckings and the sensational rumors that have since arisen.” Those rumors seemed to refer to unfounded accusations that the DesRon 11 sailors had been drinking on board ship (especially scandalous during Prohibition).

Was Denby simply reacting, or overreacting, to press calls for open sessions following initial word that the inquiry would be held in secret? Or was he recasting himself as a conscientious, diligent steward of the Navy? Denby already had been on the record as Navy Secretary talking tough about accountability. During a spate of mail robberies in 1921, he’d ordered Marines to ride in mail trucks and rail cars, issuing an order: “When our Corps goes in as guards over the mail, that mail must be delivered, or there must be a Marine dead at the post of duty.”

But other episodes raise questions about the former probation chief’s zero-tolerance approach. Several months after the Honda groundings, Denby voided the punishment—confinement, reduction in rank, and dishonorable discharge—of a seaman second class who had deserted his ship and reinstated the sailor. Denby allowed only a loss of pay, which he reduced. The sailor’s aunt had written a letter to Denby’s wife, whom she knew, asking “a favor.”

By early February 1924, the end seemed near for both the Honda case and Denby’s tenure as Secretary of the Navy. Both Democrats and Republicans had offered resolutions calling for Denby’s ouster over the Teapot Dome scandal. Senator Thomas Walsh, leading the oil investigation, accused Denby of ineptitude and stupidity worse than crime. As the Chicago Tribune described it: “Lean Walsh of Montana carved his way into the Denby fat on the floor of the Senate this afternoon.” Walsh concluded: “I desire to see him driven from public office with all the odium and ignominy that the occasion possibly can demand, in order that his fate may serve as warning to anyone who might come after him and who might otherwise fail the Republic as he has failed it.”

Disgraced But Still Standing

On 18 February, Denby’s 54th birthday, he announced his resignation. Two days later, he formally disapproved the acquittals of all officers charged with negligence in the Honda Point groundings.

“ . . . Denby was much displeased with the eight acquittals,” according to the seminal account Tragedy at Honda. “He believed that stern treatment should have been accorded all 11 of the defendants. He felt that the standards of naval discipline had been let down and that the prestige, performance, and morale of the Service would suffer.”

Further, Denby was not alone in disapproving the court’s action, Lockwood and Adamson wrote. The verdicts “created deep displeasure in Washington. The wholesale ‘hangings’ that had been expected did not materialize to provide material for political campaigners. . . . Even President Calvin Coolidge . . . observed that the ‘Court martial has been very lenient with everybody.’”

Maybe so. The Navy issued a statement saying that Denby’s disapprovals were “simply an expression of the Secretary’s views of the court’s action” and would not serve as a basis for retrying the cases.

The convicted DesRon 11 leaders were dropped enough rungs on their respective promotion ladders that neither rose in rank again. One of the acquitted defendants achieved great distinction, then-Commander William L. Calhoun (great-grandson of Vice President John C. Calhoun), who went on to celebrated service during World War II and four stars. The Teapot Dome leases were annulled. Former Interior Secretary Fall went to jail.

But Denby, for his part, eluded the “hangman’s noose.” Instead, although disgraced, he returned to Detroit and resumed practicing law. He continued to proclaim his innocence over Teapot Dome until his death ten days before his 59th birthday in 1929. All his actions, he said, had been toward “providing for the needs of the fleet. In trying to do that I have been overthrown.” He never returned to public service.

Sources:

“Denby Astonished at Navy Disaster,” Baltimore Sun, 11 September 1923.

Edwin Denby Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan: Denby, dictated memo to file, 3 March 1924; Denby, speech in Detroit, 13 March 1924; Denby, letter to Walter Brooks, 2 April 1924; Joseph J. Kennedy, letter to Denby, 26 February 1923; Theodore Roosevelt Jr., letter to Denby, 1 August 1923; Jesse H. Weston, letter to Marion (Mrs. Edwin) Denby, 22 February 1924; biography of Denby, unsigned and undated.

Frederick Essary, “Denby Finds it Hard to Smile,” Scranton Republican, 25 September 1923.

VADM Charles A. Lockwood, USN (Ret.), and COL Hans Christian Adamson, USAF (Ret.), Tragedy at Honda (New York: Chilton, 1960; reprint edition—Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1986).

William J. Losh, “Iron Man for Navy Needed,” United Press/Modesto Evening News, 19 February 1924.

Laton McCartney, The Teapot Dome Scandal (New York: Random House, 2008).

Amity Shlaes, Coolidge (New York: HarperCollins, 2013).

“2 More Destroyers Went on the Rocks,” The New York Times, 2 February 1923.

“A 2000-word sketch of Edwin Denby, Secretary of the Navy,” The Mansfield (Louisiana) Enterprise, May 19, 1921.

Gerald E. Wheeler, Admiral William Veazie Pratt, U.S. Navy (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 1974).