For ages, navies have delivered devastating gunfire on land targets in support of ground operations. The impact of such joint army-navy operations on the outcomes of land battles has been varied, unique, and significant. Such was the case in 1898—in combat at Omdurman, in the midst of the Nubian Desert along the Nile River.

It this operation, British gunboats not only contributed important firepower to an Anglo-Egyptian force, but also helped shape the battlespace—that is, influencing how the battle was to be fought—leading to victory over the warriors of the Mahdi Army and destruction of the Mahdist State.

From Gordon to Kitchener

The events leading up to the 2 September 1898 Battle of Omdurman began in January 1885, when British Major General Charles George Gordon, governor-general of the Sudan, and some 6,000 Egyptian soldiers in the besieged city of Khartoum were slain by dervishes of the Mahdi Army.

An Anglo-Egyptian relief force dispatched in July 1884 had failed to reach Gordon in time to save him and his Egyptian soldiers. In 1896, the British government sent another force into the Sudan in a two-year campaign to avenge the death of Gordon, regain Anglo-Egyptian sovereignty over the Sudan, and destroy the Mahdist state and its Mahdi Army.

The Anglo-Egyptian expeditionary force was commanded by Major General Horatio Herbert Kitchener. An able, detail-driven British Army Royal Engineer officer educated at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, he had spent considerable time in the Near East and was fluent in Arabic.

Kitchener’s major adversary was Abdullahi, known as the Khalifa. He was a brutal, suspicious, paranoid man who ruled by terror and lived in constant fear of assassination. He trusted no one, including members of his own household. He ruled capriciously, and many of his decisions, especially those concerning his god, Allah, were based on dreams that the Khalifa believed emanated from heaven.

Located northwest of Khartoum, Omdurman had become the capital of the Islamic empire by 1898. After the 1885 siege of Khartoum, Omdurman had been made not only the capital but also the tomb location of the Islamic prophet and former leader, Muhammad Amad, aka the Mahdi, who had been killed during the siege. The presence of his tomb at Omdurman made it the Mahdist State’s holiest city. The city itself was not fought over; the plain to its north was where the Mahdi and Anglo-Egyptian armies met. That the battle was fought outside the city limits played a large role in the strategy of both Kitchener and the Khalifa.

It was also meaningful when considering how Kitchener was going to use his naval assets in framing the battlefield.

Looming Showdown Where Rivers Converge

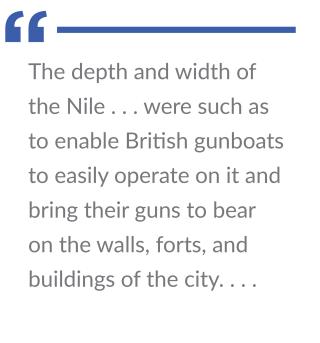

From the perspective of the Royal Navy’s participation in the battle, the location and layout of the city and its environs were important. Omdurman was situated at the confluence of the Blue Nile and the White Nile in the upper provinces of the Sudan. It lay on the west bank and stretched six miles along the river and three miles inland. The depth and width of the Nile alongside Omdurman for much of the year were such as to enable British gunboats to easily operate on the river and bring their guns to bear on the city’s walls, forts, and buildings facing the water.

Omdurman’s layout consisted of an inner core surrounded by a massive slum. The Khalifa and his family lived in relative luxury, while most of the people inhabited a maze of mud huts built one on top of the other and separated by narrow alleys and passageways that restricted movement.

The inner city, where the principal mosque, the Mahdi’s tomb, the granary, the arsenal, the Khalifa’s family houses, and the Khalifa’s residence were located, was surrounded by a great 4-foot wide, 14-foot high stone wall. Running for three quarters of a mile along the bank of the Nile, it turned inland to encompass most of this inner city and its key buildings, the most prominent of which was the Mahdi’s tomb. A series of forts outside the wall along the riverbank provided an additional element of security.

The height of the stone wall prevented direct observation from the river of all structures but one, giving defenders measured protection against any direct fire from across the Nile or from the river itself. The sole exception was the Mahdi’s tomb; the height of its upper level and dome made it an ideal aiming point for adjustment of direct and indirect cannon and howitzer fire.

For the Anglo-Egyptian expeditionary force, the river played a critical role as a logistical pathway. And for gunboats, it offered an ideal avenue of approach for bringing effective fire on Omdurman and the Mahdi troops gathered on the plain outside the city.

The time of the year when the Nile was navigable determined when the British gunboats could be deployed in support of the operation. Although the vessels’ draft was small, the depth of the river at any one time determined whether they could float over its course.

Restrictions imposed on sailing on the Nile dictated that it would not be before the beginning of September that the full force of the Anglo-Egyptian naval flotilla could be brought to bear. Six cataracts had to be passed to reach Omdurman, and the shallow depth of the river in places required Kitchener’s naval personnel and army engineers to take innovative measures to meet the river’s challenges.

In any case, Kitchener in his advance on Omdurman had complete control of the river, giving his troops a strategic advantage when it came to supplying the expeditionary force and making the British gunboats significant players before and during the forthcoming battle outside Omdurman.

Formidable Foot Soldiers

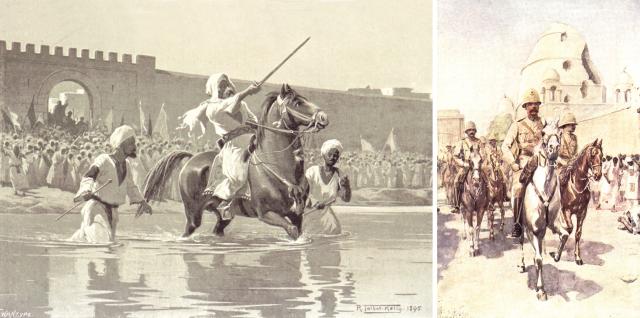

In terms of numbers and the bravery of its warriors, the Khalifa’s army was formidable. Gathered on the plain outside Omdurman were some 60,000 fanatical dervish combatants, with whom the Khalifa recently had enjoyed a number of victories when conducting offensive operations against both tribal enemies and Egyptian forces.

However, in a preliminary engagement at Atbara with a British-led contingent from Kitchener’s expeditionary force, a battle formation of one of the Khalifa’s allied emirs had been decisively defeated fighting a defensive battle.

The Khalifa ruled with an iron hand, and his decisions were to be swiftly executed. Every male capable of bearing arms was compelled to serve. In addition to what could be termed a primitive professional army, he could count on the tribes of the emirs of the realm to provide manpower when required. Tribal loyalties were fractious, however, and often required ruthless measures to keep potentially rebellious tribes in line.

The foot soldier made up the vast number of the army’s combatants. Most wore a protective vest called a jibbah, or gibbah, a padded garment that could deflect the thrust of a sword, dagger, or spear. It served as a kind of body armor, which, combined with the soldier’s fatalistic faith in Allah and promise of paradise in death, gave him all the protection he needed.

Close combat was the way the foot soldier fought best. The method worked when the opponent was similarly armed and where the employment of rifles or more sophisticated weapons was haphazard at best. The technique would work during the Battle of Omdurman when the British 21st Lancers attacked a large formation of dervishes. Assaulting the mounted troopers by slashing at their limbs, the soldiers also attacked the Lancers’ horses, cutting reins and halters and stabbing the horses themselves. But when they came against concentrated and organized rifle and artillery fire in the open, the Mahdist troops faced almost impossible odds.

The Nile Flotilla Factor

The Royal Navy had a flotilla of watercraft especially designed to operate on the Nile River—a force capable of bringing to bear firepower that the Mahdi Army could not match. That firepower consisted of cannon, howitzers, and machine guns (Maxim guns). The weapons were manned mostly by British enlisted personnel, while the gunboats were manned by Egyptian crews commanded by Royal Navy and British Army officers. In the forthcoming clash, the well-armed gunboats would operate freely and competently in providing effective fire support from the Nile to the ground operations of Kitchener’s expeditionary force.

Originally, a total of ten gunboats in three different classes constituted Britain’s Nile flotilla. It was commanded at first by Commander Stanley Colville; after he was wounded in 1896, he was replaced by Commander Colin Keppel. Among the gunboat captains who later became famous in World War I were Lieutenant David Beatty, who as an admiral in that conflict commanded the British Fleet, and Lieutenant Horace Hood, a future rear admiral who would meet his fate at the 1916 Battle of Jutland.

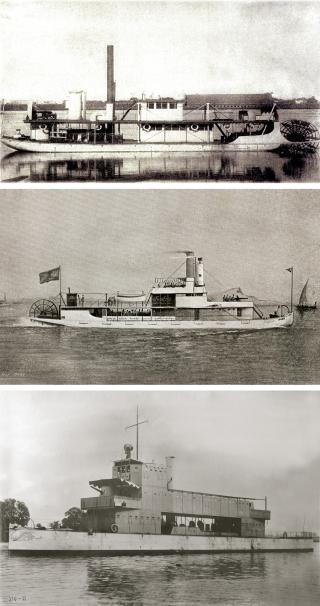

The first class of gunboats consisted of four stern-wheel craft that had been cruising the Nile since at least 1885: the Tamai, commanded by Lieutenant H. F. G. Talbot; the Hafir, commanded by Lieutenant C. M. Stavely; the Abu Klea, commanded by Lieutenant E. D. A. Newcombe, Royal Engineers; and the Metemmah, commanded by Lieutenant A. G. Stevenson, Royal Engineers. Painted black, the 90-foot gunboats were very easy to handle and had simple working parts with a draft of just 30 inches. Although characterized as lumbering, armor-plated monsters, with their speed, towing power, and small displacement, they actually were quite nimble.They also carried sufficient weaponry to demolish enemy forts along the Nile. Each gunboat was armed with a 3.5-inch, 12-pounder Krupp gun mounted forward and two .45-caliber Nordenfeldt machine guns as an upper battery.

A second class of stern-wheel gunboats, the 1896 class, was composed of the Fateh, commanded by Lieutenant Beatty; the Nasir, commanded by Lieutenant Hood; and the Zahir, carrying the flag of Commander Colin Keppel until she sprang a leak and sank before the Omdurman battle. These white-painted craft with three decks were 140 feet long with a draft of only 33 inches and could achieve a top speed of 12 knots. Like the earlier-class gunboats, they were easy to operate and maintain. Their efficient engines had large boilers that provided reserve power for towing and enabled the vessels to keep a steady speed even when burning green wood.

The 1896-class gunboats carried one quick-firing 12-pounder gun, two quick-firing 6-pounder guns, and four Maxim machine guns. One 6-pounder was mounted on the bow, the other on the stern. The Maxims, which could be moved about as needed, were fired from protected platforms some 30 feet above the water, allowing them to fire over the heads of ground troops, thus increasing their combat effectiveness and measure of safety.

The third gunboat class, the 1898 class, consisted of new, white-painted, armored, twin-screw vessels. They had been constructed in England, disassembled and divided into eight floatable sections, and shipped to Egypt. Once there, the sections were placed on railroad cars and transported to a makeshift shipyard on the Nile at Kosheh, where they were reassembled in time to participate in the attack on Omdurman. The new gunboats were the Sultan, commanded by Lieutenant Walter Cowan; the Melik, commanded by Major W. S. Gordon, Royal Engineers; and the Sheikh, commanded by Lieutenant J. B. Sparks.

These newest gunboats had hulls made of light steel, and although they had a displacement of 140 tons, their draft was only 24 inches. Good protection for the machinery compartments, deckhouses, and the conning tower was provided by quarter-inch bulletproof nickel plates. Three rudders were operated by steam steering engines while a hand tiller was available if a steering emergency required it. For navigating rapids or in case of grounding, a steam capstan provided a powerful haulage capability. The gunboats were outfitted with the up-to-date features of the day, including ammunition hoists, telegraph, searchlights, and special saws for cutting up wood for the boilers.

According to Beatty’s memoirs, however, these new twin-screw gunboats, specially designed by the Admiralty to fight on the Nile, actually were not as satisfactory as the older stern-wheel boats. They were slower than anticipated and required almost all their power for propulsion. This meant that, at times, power was lacking to drive the dynamos for ancillary devices such as the searchlights. Other shortcomings were the complicated workings of the engines and their need for skilled maintenance. Crew members working in the engine rooms also were exposed to an excessive amount of heat, which adversely affected crew performance.

Despite these performance challenges, the 1898-class gunboats carried a powerful armament punch. There were two quick-firing 12-pounder guns, one located forward and the other aft. Mounted on the forecastle was a 4-inch howitzer. For antipersonnel fire, there were four Maxim machine guns, which could be moved about as required to bear on different targets. Thus the gunboats could bring direct and indirect fire on a diverse set of material targets, such as forts and walls, as well as on personnel.

The Khalifa’s Doomed Decision

The Khalifa’s dispositions on the plain north of Omdurman were part of his aggressive plan of action to defeat Kitchener’s army. His decision was based on a dream that had told him to take the battle to the enemy, not to adopt a defensive posture.

His strategy was a risky one, as he was well aware of the firepower of his adversary (if not the special waterborne mobility provided by the gunboats). He knew the extended distance his foot soldiers would have to cover in the open to confront the defensively positioned Anglo-Egyptian infantry and artillery would mean staggering losses—but those he was willing to accept.

The Khalifa had rejected an alternative strategy that would have sharply negated the Anglo-Egyptian firepower advantage. If the Khalifa had decided to fight in the city, as some of his allies recommended, effective close combat, costly to the enemy, could have been pursued. Fighting in the narrow passageways among the warren of buildings would have meant that swords and daggers trumped machine guns and cannon.

Urban combat was just the kind of fighting that Kitchener did not want to have to engage in, if at all possible. Greatly outnumbered but boasting superior firepower, he preferred the open spaces to the confined Omdurman environs. His plan to optimize his naval and land-based gun and howitzer assets was twofold—one part physical and the other psychological.

First, the gunboats and army howitzers would bombard Omdurman targets. The objective was to produce the maximum amount of physical damage on vital targets and destroy military works. Although no amphibious attack was contemplated, once the riverside forts were destroyed and the high wall surrounding the city’s vital structures was breached, access to the city could be attained through the resulting gaps.

Second, the bombardment was designed so that the howitzers, both on board the gunboats on the opposite bank of the Nile, would deliver plunging fire into the city, persuading its fearful populace and any fighting elements deployed therein to evacuate the premises. The accomplishment of this psychological objective would facilitate any future occupation of Omdurman and lessen the potential for effective resistance from within the city.

Early on the morning of 1 September, Commander Keppel’s flotilla began an intensive bombardment of the riverbank forts, the wall, and the environs of Omdurman. Three gunboats—the Sultan, Abu Klea and Melik—made up the northern element that took the forts and riverbank huts under fire with cannon and machine guns. The Fateh, under Beatty’s command, and the Sheikh, Hafir, and Metemmeh directed their fire against the high wall surrounding the inner parts of Omdurman.

The Nasir and Tamai stood off the city in support of the Army howitzers of Number 37 Battery of the Royal Artillery, their 5-inch weapons firing 50-pound shells. While the artillerymen fired high-explosive rounds of lyddite into the city and forts with indirect fire, the gunboats unleashed direct fire on the forts and the wall.

A prime target and aiming point for the howitzers was the dome of the Mahdi’s tomb. It stood out among the buildings hidden behind the wall. Being of fragile construction, the dome was punctured by massive holes when hit. While it was not a military target, the psychological effect of the damage to the dome was great on a population and leadership who placed heavy emphasis on the heavenly protection of Allah.

With firing continuing throughout the day, the shelling wrought severe damage, and the wall was breached in several places. Although the wall had appeared to be a major protective measure, its 4-foot thickness was insufficient to survive the continual pounding of the Anglo-Egyptian weaponry. Huge gaps were created that would facilitate penetration by an attacking force.

Enemy counterfire, of which there was little, was quickly silenced. The combination of Anglo-Egyptian direct and indirect fire wrought destruction that could not be matched by the Khalifa’s relatively primitive guns. By the end of the day, the dual pummeling dealt out by the gunboats and land-based artillery had accomplished Kitchener’s two initial objectives: Overall destruction, both physical and psychological, in and around Omdurman had helped decisively shape the battlefield for the next day.

The Battle Is Joined

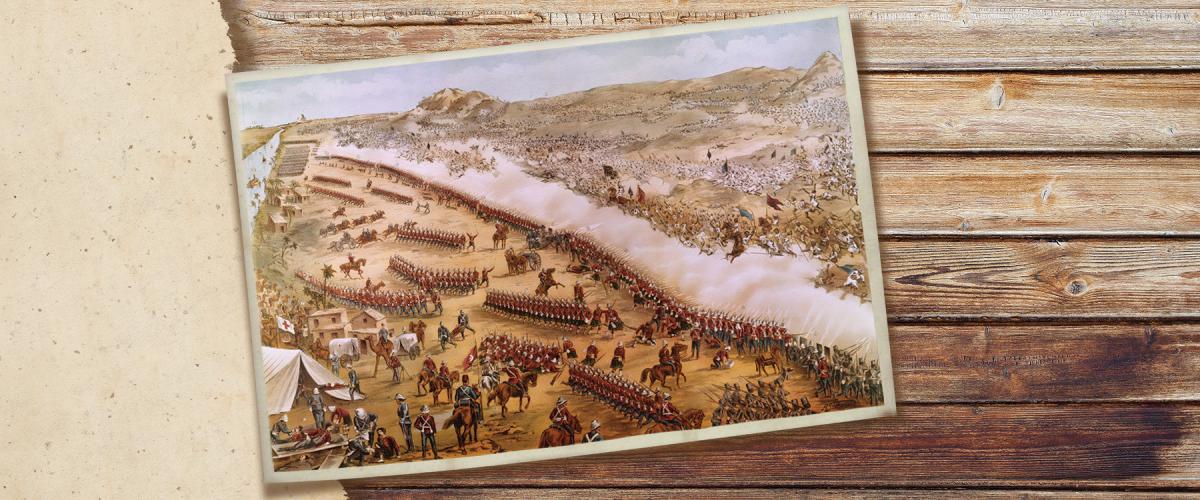

The battle that culminated in the defeat of the Khalifa began at 0625 on 2 September when the British Army’s Number 32 Field Battery opened fire at 2,700 yards on the advancing Mahdist foot soldiers. It quickly was joined by Egyptian field artillery batteries and the gunboats. The gunboats’ elevated fighting decks and bridges, along with the high waters of the Nile, made it possible to deliver effective supporting fire safely over the heads of the Anglo-Egyptian infantry and engage the enemy with direct and indirect fire from machine guns and cannon.

The gunboats’ mobility made it possible to move firepower around so it could be brought to bear wherever it was needed most. The array of weaponry on board the gunboats allowed for dealing with varied situations as they arose. The larger guns were most effective firing shrapnel at long range, while the Maxim machine guns delivered devastating close-in fire. The gunboats’ Maxims easily could be repositioned to cover dead spots while the howitzers’ plunging fire could reach the enemy in defilade positions.

Later in the morning, the Egyptian cavalry, the camel corps, and the horse artillery became in danger of being cut off from the main body of the Anglo-Egyptian force. Their annihilation was prevented by the timely arrival in their vicinity of the gunboats Melik and Abu Klea, whose Maxim gunners drove off the menacing dervishes.

By noon the battle on the plain had been won by the Anglo-Egyptian force. The Khalifa’s Mahdi Army fled in disorder. The foot soldiers scattered and abandoned any intention of rallying inside Omdurman. With a band of one of his Sudanese battalions leading the rest of his troops, Kitchener triumphantly entered the city, encountering little organized resistance. The Anglo-Egyptian Army had accomplished it mission of avenging Gordon, beaten the Khalifa’s Army, and destroyed the Mahdist Islamic Empire.

Favorable Factors for Game-Changing Gunboats

From a campaign point of view, the Battle of Omdurman was going to be a decisive contest between a selectively organized expeditionary force equipped with up-to-date armament on the defensive and a primitively armed, massive Mahdi Army on the offensive. In planning for the battle, the risk the Khalifa took in fighting outside the city proved to be a mistake. By eschewing the advantage of being able to conduct close combat in urban battle, he allowed Kitchener to maximize his tremendous army and navy firepower potential in the open, on land and on the Nile, making success a problematic prospect for the Mahdi Army.

The condition of the Nile River on 2 September allowed Kitchener’s nine battle-ready armored gunboats, armed with a wide range of weaponry, to easily sail to locations on the river from which their armaments’ firepower could be maximized in support of the ground troops during the battle.

While the Khalifa pinned his hope for success on overwhelming the Anglo-Egyptian troops with sheer mass of numbers, Kitchener executed a limited two-day operation that enabled him to bring his superior state-of-the-art firepower to bear. On the first day, he had shaped the battlespace through direct and indirect fire from his gunboats, aided by Army howitzers, on urban targets, forts, and walls, thereby discouraging the Khalifa and his allies from remaining in the city and making it the battleground. The gunboats proved to be a valuable tool employed for a unique psychological as well as physical purpose. On the second day, the gunboats added overhead long-range firepower heft to the conflict, while their machine guns saved the expeditionary force’s mounted troops from being overwhelmed.

The contribution of the gunboats to the successful outcome of Kitchener’s 1898 combat mission in the Sudan was multifaceted and significant—and the Battle of Omdurman would go down in history as an excellent example of the impact that devastating naval gunfire can have on land targets in support of ground operations.

Sources:

Ernest N. Bennett, The Downfall of the Dervishes (New York: Methuen & Co., 1899).

Bennet Burleigh, Khartoum Campaign 1898, or the Re-conquest of the Soudan (London: Chapman & Hall Ltd., 1899).

W. S. Chalmers, The Life and Letters of David Beatty (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1951).

Winston S. Churchill, My Early Life (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930).

Winston S. Churchill, The River War: An Historical Account of the Reconquest of the Soudan (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1899).

LT Charles Parnell, USN, “Gunboats In the Desert,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 94, no. 11 (November 1968): 74–90.