In the fall of 1983, the Caribbean island nation of Grenada became an overnight flashpoint in the geopolitical standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union and its primary ally, Cuba. It was an inauspicious place for the Cold War to burst into flames, but history is sometimes the plaything of chance.

On Tuesday, 25 October, the U.S. Atlantic Command—the multiservice headquarters in Norfolk responsible for the Caribbean area—launched what was at the time the largest American combat operation since the Vietnam War. In two days, with a week of mopping up afterward, a multiservice force of 6,500 Marines, Army Rangers, paratroopers, and elite Special Operations commandos—backed up by naval and air support—overpowered a small Grenadian army of about 700 soldiers and another 690 Cubans (all but 40 of whom were lightly armed airport construction workers). More than 600 American students at St. George’s University Medical School and about 200 other civilians were safely evacuated back to the United States.1

Admiral Wesley L. McDonald, who as commander-in-chief of Atlantic Command (CINCLANT) presided over the operation, later told the House Armed Services Committee that Operation Urgent Fury had been “a complete success”:

All phases of the assigned mission were accomplished. U.S. citizens were protected and evacuated. The opposing forces were neutralized. The situation stabilized with no additional Cuban intervention, and a lawful democratic government is being restored.2

The admiral’s superiors in the chain of command fully agreed. Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger later acknowledged that while the intervention had been “very hastily put together” in response to the sudden emergency, “It would be hard to say . . . that it was not successful.” In a speech to the nation, President Ronald Reagan said, “I can’t say enough in praise of our military . . . who planned a brilliant campaign and those who carried it out.”3

If it were only that simple.

In the four decades since Urgent Fury was planned in haste beginning on 19 October and executed just six days later, most of the details enabling a comprehensive account of the operation have become available. The inescapable conclusion is that the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines who achieved victory in Grenada did so in many instances despite a U.S. military command structure all but hobbled by its own internal flaws. These included persistent interservice rivalries; flawed communications; excessive secrecy; and as one expert witness lamented, “unforgivable blunders” in vital intelligence-gathering before and during the invasion. One set of numbers is revealing. A total of 24 U.S. servicemen were killed on Grenada. Of those, 14 died in combat actions marred by intelligence failures.4

A Sudden Crisis

With a land mass just twice the size of the District of Columbia, Grenada for much of its history was a Caribbean backwater. In the 1970s, under the mismanagement of Prime Minister Eric Gairy, Grenada’s economy languished, and its residents suffered from the regime’s widespread corruption. In 1979, attorney Maurice Bishop and his leftist New Jewel Movement (NJM) ousted Gairy in a bloodless coup.

Bishop quickly aligned the new government with Fidel Castro’s Cuba and began implementing socialist rule throughout the island, forcing most businesses to go under, closing the two newspapers, and enriching the leaders of the People’s Revolutionary Government. By early 1983, the regime had its hand in nearly all facets of the Grenadian economy.

With the help of Cuba and the Soviet Union, Grenada launched a multiyear plan to build an outsized People’s Revolutionary Army (PRA) financed and armed by Havana and Moscow with promised arms and equipment totaling $25.8 million. A key part of the infrastructure was the completion of Point Salines Airport at the southern tip of Grenada.5

Grenada was becoming a failed state by 1983. A hard-line NJM faction partly led by Deputy Prime Minister Bernard Coard sought to oust Bishop and move the country even closer to the Soviet Union. Matters came to a head on 13 October 1983, when Coard ousted Bishop as prime minister and placed him under house arrest.

The arrest of Bishop, still a popular public figure, sparked mass demonstrations on Wednesday, 19 October, and a crowd freed Bishop. In response, PRA soldiers loyal to Coard machine-gunned the protesters, killing about 40 and wounding dozens more. Several hours later, they executed Bishop and seven of his supporters. By nightfall, Grenada was in total chaos, and its residents cowered in their homes under a shoot-to-kill curfew ordered by Coard’s newly formed Revolutionary Military Council.6

The events of “Bloody Wednesday” set the stage for Operation Urgent Fury.

Come as You Are

The initial goals of the U.S.-led intervention were straightforward: rescue 600–800 American medical students and expatriates, neutralize the RMC, and stabilize the country. But factors both external to the U.S. military and deeply embedded in its marrow would make the operation both overly complex and significantly controversial. Those factors included:

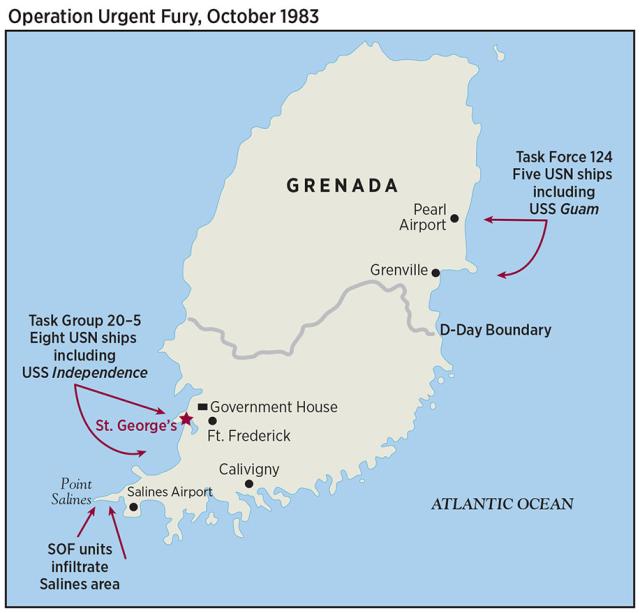

Minimum timing: When formally tapped to organize and execute Operation Urgent Fury, the U.S. Atlantic Command found it had just 72 hours to plan the invasion, select combat units to carry out a variety of missions, deploy the force, and then launch the attack. After diverting the 22nd Marine Amphibious Unit (MAU) from a scheduled deployment to Beirut, along with the USS Independence (CV-62) carrier battle group, the force was expanded to include several groups of elite Navy SEALs, Army Delta Force commandos, and Army, Navy, and Air Force aviation units; two Army Ranger battalions; and two brigades from the 82nd Airborne Division.

Extreme secrecy: In an attempt to ensure operational security, General John W. Vessey Jr., Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS), imposed “special category” Top Secret restrictions on all communications, severely limiting planning information to a short list of intelligence and operations staffs at the Pentagon and Norfolk. Support units vital to logistics, resupply, and medical evacuation were kept in the dark. Freezing out all public-affairs units resulted in the exclusion of the press from the operation, which would strain the relationship between the Pentagon and the U.S. news media for years.7

Flawed command-and-control: Because Grenada fell into U.S. Atlantic Command’s area of responsibility, Admiral McDonald was the theater commander for Urgent Fury. He tasked 2nd Fleet commander Vice Admiral Joseph Metcalf III as commander of Task Force 120, the operational command including all Navy, Marine Corps, Army, and Air Force combat units. Realizing that the two naval aviators lacked detailed knowledge or experience in ground combat operations, the Army pressed for experienced staff planners to assist on the scene.

Instead, Major General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, commander of the 24th Infantry Division at Fort Stewart, Georgia, found himself appointed at the last minute as an “adviser” to Metcalf on board his flagship, the helicopter carrier USS Guam (LPH-9). The general later recalled, “I realized I wasn’t even sure where Grenada was. . . . I knew it was a Caribbean island, but I’d have been hard pressed to find it on a map.”8

Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger threw an additional monkey wrench into the command-and-control structure at the last minute. Deciding to get more personally involved, he appointed General Vessey as overall commander-in-chief of Urgent Fury over McDonald. This was a drastic departure from the JCS Chairman’s official role as senior military adviser to the Defense Secretary and President (with actual operational authority resting with the combatant commanders-in-chief such as McDonald at Atlantic Command). Weinberger then ordered Vessey to double the size of the force. This added the multiservice Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) for its elite Rangers, Navy SEALs, and Delta Force commandos and expanded the planning roster to include the Military Airlift Command.

One unavoidable consequence of Vessey’s new operational authority was that Admiral Metcalf on board the Guam now would have both McDonald’s Norfolk staff and the 1,000-man Joint Staff in the Pentagon looking over his shoulder. There would be consequences.9

Lack of intelligence: From the outset of the emergency beginning with Bishop’s execution, planners ranging from the White House to individual combat units urgently reached out for essential intelligence information. There was no information available. The CIA disclosed it didn’t have a single agent on the island. Worse, a National Security Agency employee whose brother was a medical student at St. George’s reported the existence of a second medical school campus at Grand Anse, but the information never reached the troops on the ground.10

“To the amazement—and consternation—of all who wanted information, virtually none was available,” author Mark Adkin wrote in his comprehensive history of the intervention, Urgent Fury: The Battle for Grenada. “There were not even any proper maps with grid coordinates.” The only available maps were ancient tourist maps obviously lacking precise coordinates essential in locating and targeting the enemy. No one even knew if the runway at Point Salines was usable for C-141B and C-130 cargo aircraft, or if the PRA had blocked it.”11

Communications failure in planning: One extreme example concerned the obvious military target of the 9,000-foot runway at Point Salines Airport.

When alerted to prepare for possible involvement in the Grenada intervention on Friday and Saturday, 21–22 October, yet excluded from most details of the preparations, three separate military commands began independently planning to capture the airport. The 22nd MAU (embarked with a Marine helicopter squadron in the Guam amphibious ready group), the 82nd Airborne Division, and JSOC (which in addition to its commandos controlled the elite Air Force 1st Special Operations Wing) all chose the predawn hours of D-day, 25 October, unaware of the others.

In short, less than 72 hours before the invasion, the stage was being set for the largest midair collision in the history of flight. Disaster was averted at the last minute when the Atlantic Command issued its formal operational plan on Sunday, 23 October. It specified the missions: Preceded by a team of SEALs and Air Force pathfinders, the Rangers would take Point Salines (to be relieved at midday by 82nd Airborne paratroopers); the Marines had the new mission of capturing Pearls Airport and the northern half of the island. The 160th “Night Stalkers” would fly other JSOC commandos on special missions around St. George’s.

Elsewhere, poor communications at all levels marred the operation in a wide variety of ways. While plans for Urgent Fury called for a 400-man Caribbean Peacekeeping Force from a half-dozen neighboring countries, this never made it into CINCLANT’s operational plan. So when the peacekeepers arrived at Point Salines at mid-morning on 25 October, they had no idea of their mission; worse, their U.S. counterparts had no idea they were coming.

Other communications mishaps had dire consequences. Throughout the three days of fighting, radio communications between Admiral Metcalf and his commanders ashore were “poor to nonexistent,” according to Major General Edward Trobaugh, commander of the 82nd Airborne Division. A naval fire-control team supporting ground troops found it could not communicate with the battalion it was assisting; as a result, a hasty call to Navy A-7 aircraft to suppress a PRA sniper resulted in a friendly-fire incident that wounded 17 paratroopers, of whom one later died.12

Military “Pie-dividing”: JSOC in 1983 included elite Army, Navy, and Air Force units under Army Major General Richard Scholtes in a structure aimed at increased cohesion and interservice training. Still, Scholtes faced serious pressure from the various services to include as many—if not all—of their components in Urgent Fury. JSOC planners began hastily picking as many targets as possible and assigning specific units to carry out the attacks. One post-conflict analysis concluded several JSOC missions were nonessential. A key reconnaissance mission failed disastrously.13

Going in Blind on D-day

Nineteenth-century Prussian Field Marshal Helmut von Moltke famously observed, “No plan survives first contact with the enemy.” Operation Urgent Fury was different: The plan for D-day collapsed a full day before U.S. and PRA troops even started shooting at one another.

With no accurate maps or recent aerial photographs to depict the Point Salines runway, Major General Scholtes at JSOC selected a group of four elite Air Force combat controllers to infiltrate the island on 24 October. Their mission was to ensure the runway was clear of obstacles and to install beacons and other navigation aids for the ten C-130s bringing in the Rangers the next morning.

This vital pre-invasion mission ended in tragic failure, in part because of a last-minute change forced on Scholtes by the Navy. In the original plan, the Air Force pathfinders would parachute from a C-130 into the sea offshore, then swim to a motor whaleboat launched from the frigate USS Clifton Sprague (FFG-16) standing by the drop zone. When Scholtes added 12 SEAL Team 6 commandos, the mission ballooned: Now there were two C-130s dropping two teams of eight swimmers near the frigate where two motor whaleboats would be waiting.

One C-130 pilot inexperienced in low-level night insertions missed the mark, and four SEALs were swept away and drowned. The others had to abort the mission when heavy seas swamped the boat and killed her engine. A second attempt in the predawn hours of D-day failed the same way. Absent maps, aerial photographs, and a reconnaissance report, the Rangers were going in blind.14

The hastily compiled operation plan for Urgent Fury consisted of seven specific objectives to be completed by sunset on D-day, Tuesday, 25 October:

• In the north, SEAL Team 4 members would inspect surf conditions, then the 22nd MAU would seize Pearls Airport and begin expanding its patrol area to the west and south.

• A group of SEAL Team 6 commandos would seize the Radio Free Grenada transmitting station at Beausejour.

• Two Ranger battalions would capture Point Salines Airport.

• Soldiers from the 1st Ranger Battalion would secure the medical students at the True Blue campus located near the eastern end of the runway. The initial battalion of 82nd Airborne soldiers would assume control of the airport.

• Soldiers from the 2nd Ranger Battalion would march overland to seize the main PRA base on the Calivigny Peninsula.

• In St. George’s, five Army MH-60 Blackhawk helicopters from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment would land a joint team of Rangers and Delta Force at Richmond Hill Prison to free political prisoners.

• Another Blackhawk formation would land a SEAL Team 6 platoon at Government House to rescue Governor-General Sir Paul Scoon. (See “Secret Mission of Urgent Fury,” October 2021, pp. 26–33.)

As an optional task once primary objectives were met, SEAL Team 6 members would capture the city power station.

When the sun went down on the 25th, only two of the mission tasks had been completed. The Rangers had secured Point Salines Airport, enabling the 82nd Airborne troops to begin landing. And the Marines had flawlessly captured Pearls Airport in a heliborne assault after SEAL Team 4 members found surf conditions too severe for amphibious entry.

An Overestimated Enemy

From the start of mission planning, the officials at the Pentagon and Atlantic Command headquarters had no precise picture of the threat posed by the PRA and its reserve militia. The Defense Intelligence Agency estimated the invasion force would encounter between 1,000–1,200 regular PRA soldiers and between 2,000–5,000 militiamen, along with 300 or so Cubans, but officials dismissed the PRA as “militarily ineffective.”

In fact, only 450 regular PRA troops and 250 militiamen out of a paper force of 3,000 took to the field, and most of them quickly abandoned the fight. The mass killing of demonstrators and the execution of Maurice Bishop had turned the vast majority of Grenadians against Coard and the RMC.15

However, two small units within the PRA would defeat or thwart the elite Delta Force, SEALs, and the “Night Stalkers” aircrews on D-day. The PRA had a 90-man Motorized Company equipped with eight Soviet BTR-60PB armored personnel carriers (each mounting a heavy 14.5-mm turreted machine gun) and a 45-man antiaircraft battery armed with four mobile Soviet ZU-23 twin-barrel antiaircraft guns. In three of the five special operations missions, PRA soldiers with this equipment significantly outgunned the U.S. commandos, who carried only light weapons.16 And the tiny PRA antiaircraft battery with its 1950s-era manually fired guns shot down an MH-60 Blackhawk and two Marine AH-1T Cobra helicopters and damaged another five Blackhawks. Its gunfire from Fort Frederick drove off the Richmond Hill Prison rescue mission.

Despite these and other setbacks, by nightfall on 25 October, Task Force 120 had firmly taken ground on Grenada, controlling Point Salines and Pearls Airports. Three follow-on 82nd Airborne battalions were on the ground, although the Ranger redeployment had been canceled. Apprised of the SEALs at Government House, who were trapped as a PRA armored car perforated the building with gunfire, Admiral Metcalf ordered the 22nd MAU to send Company G of the 2/8 Battalion Landing Team ashore with five M-60 tanks and 17 LVTP-7 amphibious assault vehicles. The objective was to rescue Governor-General Scoon and his encircled SEAL defenders, which the Marines carried out smoothly the next morning.

Soldiers or Marines?

However, the primary mission of Operation Urgent Fury of rescuing the medical students had become a textbook on failed military planning, thanks again to poor intelligence.

Two hours after the parachute assault on Point Salines, Rangers from A Company 1/75 reached the True Blue campus and quickly drove off a handful of PRA gate guards. The joyous encounter between soldiers and students did not last long; the Rangers were shocked to learn that more than half the students were at a second campus at Grand Anse, two miles away. Apprised of this stunning revelation, Major General Trobaugh realized that an overland approach likely would force Cuban and PRA soldiers from their known positions into the campus. He decided that only a heliborne assault would work, but he had no Army helicopters on the island yet.

At 1600 hours on Wednesday, 26 October, a rare joint operation involving Marine helicopters from the Guam carrying 2nd Ranger Battalion soldiers conducted a flawless assault from the sea at Grand Anse, rescuing 224 students with no casualties. Speaking before the House Armed Services Committee, General Trobaugh later praised the rescue as confirming “the ability of the services to come together and in very short order . . . to accomplish a mission. . . . I think it is a testimony to the joint training that we are trying to do in the services.”17

It wasn’t until nine years later that General Schwarzkopf revealed that the Grand Anse mission had sparked a brief but ugly episode of interservice rivalry while the students were in danger. The Guam had arrived off Grand Anse beach on the morning of 26 October, but no Army helicopters were yet available at Point Salines. Schwarzkopf proposed that the Guam’s helicopters be used to pick up the Rangers and Airborne troops to rescue the students, and Admiral Metcalf readily agreed.

But when approached, the senior Marine refused, saying. “We don’t fly Army soldiers in Marine helicopters.” Schwarzkopf replied, “Listen to me very carefully, colonel. This is a direct order from me, a major general, to you, a colonel, to do something that Admiral Metcalf wants done. If you disobey that order, I’ll see to it that you’re court-martialed.” The colonel finally relented.18

Tragedy in the Wake of Success

By the morning of Thursday, 27 October, the battle for Grenada was essentially over. As would later be learned, Bernard Coard and the Revolutionary Military Council had thrown in the towel on Wednesday, shedding their uniforms and slipping away to hide until their inevitable arrests. The last of the Cubans had surrendered. Despite the bottleneck at Point Salines Airport, which could accommodate only one transport aircraft at a time, 82nd Airborne reinforcements steadily arrived, growing to six battalions on the island. Except for the Rangers, the Special Operations units redeployed to the United States. It seemed over.

But orders suddenly flashed in from Norfolk at midday ordering Metcalf and Trobaugh to mount one last major combat assault—on Calivigny barracks, four miles east of Point Salines. It was a D-day objective that had been sidestepped because of pressing needs elsewhere. “The Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted us to take the Calivigny barracks by the end of the day,” Schwarzkopf recalled. “Intelligence sources reported it to be a Cuban terrorist training camp.” Admiral Metcalf protested the mission as unneeded and received a terse follow-up: “JCS orders you to take the Calivigny barracks by tonight.”

An intense bombardment from Army howitzers, Navy and Air Force aircraft, and several warships preceded the assault. Due to poor communications and inadequate rangefinders, most bombs and shells fell short into the water. Three 2nd Ranger Battalion companies and one from the 1st Ranger Battalion mounted 16 Blackhawks after a hasty hour of preparation.

Calivigny barracks, it turned out, was empty of PRA soldiers and AA guns. Three of the four Blackhawks attempting a hasty landing crashed, killing three Rangers and badly injuring four more.19

The needless loss of life at Calivigny barracks prompted a disappointingly familiar exercise in blame avoidance back in Washington and Norfolk. As Adkin described it in Urgent Fury, when XVIII Airborne Corps commander Lieutenant General Jack V. Mackmull conducted an informal investigation to find out who had sent the abrupt order to Metcalf, “He could find no evidence that the order had originated with the Joint Chiefs of Staff or the Joint Staff. He was also convinced that . . . Admiral Wesley L. McDonald, had not ordered the attack.” Mackmull’s “best guess” was that an unidentified Atlantic Command staffer had added the “JCS directs” to the message.20

A Political Win

In the end, despite the serious flaws that hobbled the operation and cost the lives of servicemen, Operation Urgent Fury was an overwhelming political victory for the Reagan administration and was hailed by the vast majority of Grenadians. Despite enduring economic problems, Grenada reverted to a democratic government and has enjoyed relative stability in the decades that followed. 25 October is a national holiday on Grenada.

While obscured by the high security that permeated Urgent Fury, the flaws that seriously hampered the operation did not go unnoticed by senior military leaders and defense-minded members of Congress. Along with other post-Vietnam failed operations—the 1980 Iran rescue raid, the 1983 Marine peacekeeping mission in Beirut—Grenada provided concrete evidence of what needed to be changed to make the American way of war more effective, more efficient, and safer for those who fight. Three years after Point Salines, Congress passed the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act, which has been credited with creating significantly improved interoperability among the armed services.

The lessons from Grenada were learned.

1. House Armed Services Committee (HASC), “Hearing on the Lessons Learned as a Result of the U.S. Military Operations in Grenada,” 30, 24 January 1984, reprinted by University of Michigan Libraries Collection; Mark Adkin, Urgent Fury: The Battle for Grenada (Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Lexington Books, 1989), 159.

2. HASC, “Lessons Learned,” 17.

3. President Ronald Reagan, “Address to the Nation on Events in Lebanon and Grenada,” 27 October 1983, reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/address-nation-events-lebanon-and-grenada.

4. Ronald H. Cole, “Operation Urgent Fury—Grenada,” Joint History Office, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Washington, DC, 1997, 61; see also Adkin, Urgent Fury, 189, 202–3.

5. Adkin, Urgent Fury, 22.

6. Edgar F. Raines Jr., The Rucksack War: U.S. Army Operational Logistics in Grenada, 1983 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2010), 71–73.

7. Cole, “Urgent Fury,” 4.

8. Cole, 7; GEN H. Norman Schwarzkopf, USA (Ret.), It Doesn’t Take a Hero (New York: Bantam Books, 1992), 246.

9. Raines, Rucksack War, 164.

10. Robert M. Gates, From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider’s Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007), 275; Adkin, Urgent Fury, 150.

11. Adkin, Urgent Fury 129–30.

12. Adkin, Urgent Fury, 220–22.

13. Analysis of Urgent Fury by Senate defense aide William Lind, reprinted in Adkin, Urgent Fury, 346.

14. Adkin, Urgent Fury, 167–70.

15. Adkin, Urgent Fury, 157.

16. Cole, “Urgent Fury,” 17–20; Schwarzkopf, Hero, 247; Raines, Rucksack War, 17–19; and Adkin, Urgent Fury, 140.

17. Adkin, Urgent Fury, 215; LtCol Michael J. Byron, USMC, “Fury from the Sea: Marines in Grenada,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 110, no. 5 (May 1984): 118–31; Raines, Rucksack War, 345–46; and HASC, “Lessons Learned,” 27.

18. Schwarzkopf, Hero, 254–55.

19. Schwarzkopf, Hero, 256; Adkin, Urgent Fury, 279–84.

20. Raines, Rucksack War, 516.