Most Americans who remember Operation Urgent Fury—the October 1983 U.S.-led invasion of Grenada—recall it as a contingency action to protect U.S. citizens on a tropical island then in the throes of a bloody power struggle. “Rescue mission” became the Reagan administration’s preferred shorthand phrase for describing, and justifying, the multinational intervention.

That messaging was affirmed on the second day of the eight-day operation. At 1719 on 26 October 1983, the first planeload of Americans evacuated from St. George’s University Medical School on Grenada landed at Charleston Air Force Base in South Carolina. One student dropped to his knees, spread his arms, and kissed the runway. That image appeared on live TV network broadcasts, and later on newspaper front pages, around the county. As soon as President Ronald Reagan’s chief press spokesman saw that gesture of gratitude, he exulted. “That’s it! We won,” Larry Speakes shouted as his staffers cheered and pounded the table.1

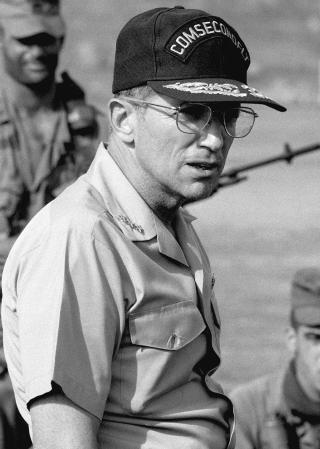

But the domestic public-relations battle that was essentially won with a single kiss was not the same fight that was being waged by Vice Admiral Joseph P. Metcalf III, the on-scene invasion task force commander.

Another rescue—a top-secret mission at the time—was Metcalf’s overriding concern on D-day in Grenada. Even today, that story is shrouded in diplomatic intrigue and military secrecy. But over the past 38 years, enough bits and pieces of the drama have surfaced in memoir accounts and declassified documents to assemble a coherent, if still incomplete, account.

The other rescue on 25 October 1983 involved a genteel educator-turned-civil-servant: Sir Paul Scoon, the island’s native-son governor general. Scoon, the resident head of state in the former British colony, was a pivotal player—because Operation Urgent Fury involved more than just the safe evacuation of U.S. citizens.

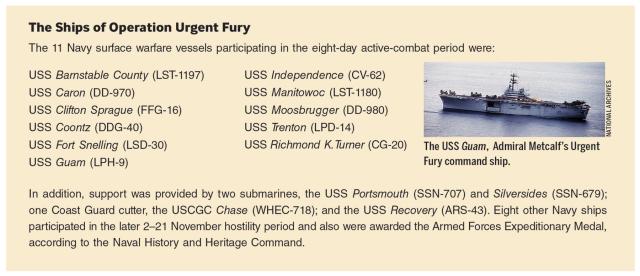

Reagan’s then–top secret National Security Decision Directive 110A also set out two other objectives: restoration of democracy on the communist-led island, and neutralization of Cuban and Soviet influence over the erstwhile British territory. These “regime change” imperatives were added late in the planning process and begged a larger force than would have been required just to execute a noncombatant evacuation operation. The final Operation Urgent Fury plan called for the island to be taken with a coup de main, a French term for a swift, sudden blow. In this application, the coup de main involved 11 U.S. Navy surface combat ships cordoning off the island while a battalion of shipborne Marines landed on the northeastern coast to seize Pearls Airport and the port town of Grenville.2

Simultaneously, two Army Ranger battalions, flying directly from Georgia, would parachute on Point Salines on the island’s southwest coast. The Rangers would seize the new airport being built there by 600-odd Cuban workers and then link up with American medical students living at a campus located just off the eastern edge of the unfinished runway.

A third force of about 100 counterterrorism commandoes were supposed to arrive simultaneously by Army Blackhawk helicopters from Barbados. They were assigned to three politically sensitive classified missions: free political prisoners from a ridge-top prison, capture the island’s main radio transmitter station, and secure Governor General Scoon at his official residence.

Scoon was the linchpin of the entire operation. He was regarded in the Eastern Caribbean as Grenada’s last legitimate governmental authority at a time when the nation’s established cabinet had dissolved after the fratricidal executions of four minsters. The island teetered on the brink of civil war.

Firing Squad for a Prime Minister

Two weeks before the invasion, on 12 October, a simmering leadership struggle within Grenada’s Leninist-style ruling party had come to a boil. Maurice Bishop, the island’s populist prime minister, was pressured to share power with his more dogmatic deputy, Bernard Coard. When Bishop balked, the party’s Central Committee, now under Coard’s sway, ordered him held under house arrest.

When Bishop’s confinement became broadly known, thousands of his ardent supporters marched on his home on 19 October and set him free. Bishop next led the crowd to bloodlessly seize control of Fort Rupert, the island’s military headquarters. Other Grenadian regular Army soldiers loyal to the Coard faction then were dispatched in three armored vehicles to retake the fort and recapture Bishop. Shooting started when the soldiers faced off with Bishop’s supporters at the fort’s entrance. Three soldiers and at least eight civilians were killed in the ensuing melee and panic that also injured about 100 other civilians.

The surviving soldiers captured Bishop, three of his ministers, and four other loyal supporters and led them away to a walled courtyard. Shortly after, the eight were executed in cold blood by a firing squad of soldiers who (according to subsequent court testimony) declared they were acting under the orders of the Central Committee.3

The Grenadian military then took control and formed an interim ruling council of Army officers. To forestall any further public protests, a five-day, around-the-clock, shoot-on-sight curfew was imposed on the island of 90,000 people.

This convulsive use of brute force shocked Grenada’s island neighbors and gave rise to fears of more internecine bloodshed or Cuban/Soviet military intervention—or both. Governor General Scoon skirted the turmoil because he was regarded as a malleable figurehead by the firebrand leftist revolutionaries who had been running the country since seizing power in a coup on 13 March 1979. Scoon had assumed his mostly ceremonial role as the local representative of Queen Elizabeth II just five months earlier. He accepted Bishop as the new de facto prime minister, based on the populace’s broad support for the Bishop-led coup compared with the “widespread unpopularity” of ousted Prime Minister Eric M. Gairy.4

Bishop and his top deputy, Coard, became the governor general’s nearest neighbors and arm’s-length governing associates. Ideologically, Scoon was poles apart from the two younger men. He was an observant Catholic and an Anglophile committed to democracy, the Commonwealth, and the Queen. The revolutionary regime presented itself to the world as nonaligned and socialist, but its leaders looked to Marx and Lenin for their political guidance—and the Soviet Bloc for military and economic aid.

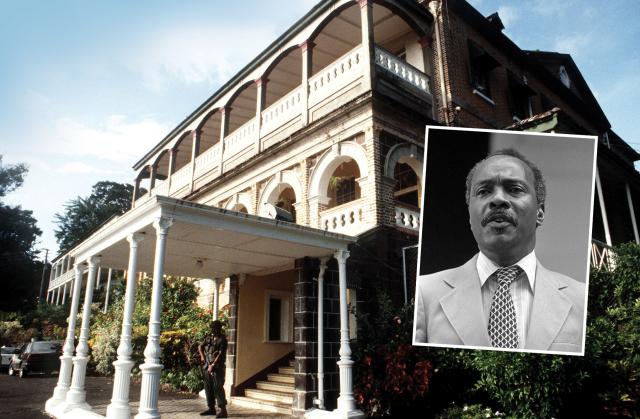

Scoon lived and worked in a three-story, Georgian-style mansion, officially known as Government House, majestically situated on a hill overlooking the picturesque, red-tile-roofed capital of St. George’s. U.S. officials consistently described Scoon’s pre-invasion status as “under virtual house arrest,” but he exercised considerable freedom of action, even after Bishop’s assassination. During the ensuing curfew period, Scoon met with foreign diplomats and also held discussions with the new military junta about forming a new civilian government. Scoon also was allowed to receive international phone calls from Caribbean leaders and England. On 22 October, Queen Elizabeth II’s assistant private secretary called. Scoon assured him that he and his wife were under no threat and were both in “good form.”5

The next day, Scoon also had a private, off-the-guest-book meeting in his garden with David Montgomery, a visiting diplomat from the British regional embassy on Barbados. Montgomery briefed Scoon on the discussions that Grenada’s anxious Caribbean neighbors were having among themselves, and with Britain and the United States, about the need to restore the rule of law in the Windward Islands. Montgomery asked Scoon if he would support, in writing, a U.S.-led military intervention.

Scoon temporized. By his later account, he told Montgomery he feared for his life if he “directly challenged” the military junta’s authority,” but he did authorize Montgomery to pass along his oral request for “military action by friendly states” to restore order on the island.6

Montgomery’s written report of the conversation to London, however, made no reference to any invitation to intervene from Scoon. Accordingly, the British Foreign Minister interpreted Scoon’s pre-invasion statements as not asking for any help of any kind through representatives of either the British Foreign Service or Buckingham Palace.7 But other interested parties elsewhere took Scoon’s guarded remarks as a green light. Intervention advocates in both the United States and the Caribbean later stated that they based that view on other vaguely described, back-channel signals they got from Scoon prior to the invasion.8

Black Hawks Over Government House

Scoon woke on D-day, 25 October, to the roar of two Task Force 160 Black Hawk helicopters hovering over his bedroom. The aircraft carried two dozen Navy SEALs, who planned to drop into the front and back yards of Government House. One helicopter also carried two CIA employees and a State Department political officer.9 The trio carried a letter for Scoon to sign that would formally request the intervention that was already under way.

However, before the civilians could be unloaded, their helicopter maneuvered away from the mansion to avoid opposing ground fire from uniformed Grenadians. That repositioning exposed the Black Hawk to crew-served antiaircraft fire coming from two forts in the capital city.10 One round ripped through the cockpit floor, tore a softball-sized chunk of flesh out of the air mission commander’s left leg, and knocked him into shock. The other pilot took control of the aircraft and headed out to sea to seek medical help for the wounded Army major—with the civilians and the SEAL commander still on board.

The Black Hawk landed hard, without permission, on the flight deck of the USS Guam (LPH-9), Metcalf’s flagship.11 The aircraft’s radio was inoperative, and the engines would not shut down. Deck crews used fire hoses to drown the runaway turbines with seawater.

Meanwhile, back at the mansion, 22 Navy SEALs had fast-roped to the ground without their boss, Captain Robert A. Gormly, the SEAL Team 6 commander, or their satellite radio. Both had unexpectedly flown off on the stricken helicopter.12 The assault team leader, Lieutenant Wellington T. “Duke” Leonard, a decorated Vietnam veteran, was now the ranking SEAL officer on the ground.

Scoon, his wife, and their nine-person retinue fled to the mansion’s cellar when the shooting started outside. When Scoon heard shouts from above, he ordered his staff to show themselves to the searchers. The SEALs took Scoon’s entourage in hand and then cleared the mansion’s rooms of any hidden threat.13

The Grenadians who had been firing at them on landing had retreated. The SEALs had planned a helicopter extraction of Scoon’s group within 45 minutes of their arrival. But that quick exit was now in doubt given the enemy resistance they encountered. The SEALs took up defensive positions in and around the mansion and waited for another escape option to develop.

Small-arms fire directed at the house started to pick up. A rifle-fired grenade exploded in one of the vacant rooms. The SEALs moved the civilians into the upstairs dining room, where they were better shielded from the Grenadian military forces that surrounded them. Grenadian antiaircraft guns and mobile infantry had been positioned nearby to defend all the official residences in the hilltop neighborhood.

While the mansion raid was devolving into a siege, Gormly, the SEAL commander, flew from the Guam to a special forces command post at Point Salines Airport. There he was able to establish contact with the embattled SEALs six miles away at Government House, who were individually equipped with handheld MX-360 tactical radios of limited range and battery life.14

SEALs Under Siege

At around 1000, Grenadian infantry approached on foot from the northwest, while a turreted armored personnel carrier (APC) advanced on the mansion by road from the southeast. The SEALs needed air support to repulse the attack, but their radios could not communicate directly with the Air Force gunships flying overhead. Instead, Gormly’s radioman passed Leonard’s pleas to an Army Delta Force radioman sitting nearby. That operator communicated with the gunships using a Vietnam-era PRC-77 backpack radio that the Army and Air Force used but the SEALs did not have.15

An Air Force AC-130 Spectre arrived over the mansion at about 1015 and beat back the advancing soldiers with its 20-mm and 40-mm cannon.16 Another Spectre soon joined the fray. Together, the two gunships squelched the pincer assault, but by noontime, both had flown off separately to refuel. Gormly appealed for additional forces to relieve the besieged mansion. Metcalf was unfamiliar with this aspect of the oft-revised invasion plan, which had been drafted without his initial involvement in Norfolk and Washington. “The rescue of the governor general had not been included in any of my earlier instructions,” Metcalf later wrote. “But it soon became apparent, through talks with my State Department representatives, that his rescue was of paramount importance.”17

Metcalf was asked to attack Fort Frederick, the Grenadian command post that was directing the counterattacks on the Scoon mansion. The colonial-era fort was defended by two Soviet-made ZU-23 antiaircraft guns. Other supporting ZU-23s occupied key positions elsewhere in the capital city within line of sight of the hilltop fort.

Because of the fort’s proximity to civilian structures, Metcalf was reluctant to order bombardment by Navy ships or jets. Metcalf opted for the more precisely aimed firepower offered by Marine attack helicopters. Two AH-1Ts from the Guam were routed by an Army forward air controller toward the capital, arriving over St. George’s after 1300. The two-seat Cobras attacked the fort in tandem, one making a pass at the target while the other sought to distract or discourage any defenders.18

On the fifth attack run, at 1327, one Cobra was hit by three antiaircraft rounds. The rounds crippled both twin turbine engines, knocked out the copilot, and severely injured the pilot in the right forearm and leg. Despite his wounds the pilot, Captain Timothy B. Howard, successfully crash-landed his disabled aircraft on a sports field in the capital city. Captain Jeb F. Seagle, the copilot, regained consciousness and dragged Howard from the burning wreck.

The surviving Cobra kept Grenadian soldiers at bay with rocket fire and called for a medevac rescue. A Marine CH-46 made a daring dash to the crash scene and successfully rescued Howard. But by the time the medevac arrived, Seagle had been shot and killed by advancing Grenadian solders, according to civilian eyewitnesses.19

The remaining Cobra provided covering fire for the evacuation, but that aircraft also was hit by antiaircraft fire, killing both pilots: Captain John P. “Pat” Giguere and Lieutenant Jeffrey R. Scharver. The second Cobra crashed at sea just outside the St. George’s harbor at 1340.

The unexpectedly stout resistance at St. George’s now persuaded Metcalf to unleash Navy A-7 Corsairs from the USS Independence (CV-62) to bomb Fort Frederick. Metcalf also asked Major General Norman Schwarzkopf, his senior Army adviser, how to further relieve the pressure on Government House. The two discussed sending Marines to stage an assault on the northwestern side of the island in a classic envelopment maneuver.20 A plan was hastily drafted calling for a landing by two rifle companies of the 22d Marine Amphibious Unit. Golf Company on board the USS Manitowoc (LST-1180) would attack a narrow beach at Grand Mal Bay from 13 amphibious landing craft. Tanks and jeeps on board the USS Fort Snelling (LSD-30) also would be put ashore once the beachhead was secure. Later, Fox Company, already ashore near Pearls Airport, would be ferried across the island by Marine helicopters to supplement the amphibious force.

While this air-amphibious operation was being organized, Scoon and his party lay sprawled on the hardwood floor of his dining room. During lulls in the firing, Scoon and his wife occasionally rested on a mahogany couch under pictures of dispassionate British royals. Most of the SEALs remained outside, manning a defensive perimeter around the mansion about 25 yards away, spaced 10 to 20 yards apart.21 They were lightly armed, mostly with shoulder weapons and pistols. At one point in the day, the island’s police chief called Scoon by telephone. He inquired about Scoon’s well-being—and also asked how many Americans were with him, and how they were armed. Scoon responded that he had never seen so many guns in his life. Scoon’s coy report failed to discourage further attacks. At around 1530, a group of 30 soldiers, supported by an APC, were seen advancing on foot from the vicinity of Bishop’s nearby former residence.22 Leonard’s radio batteries were running low, so he used Scoon’s house phone to call back to the United States for help—using a long-distance calling card.23

An AC-130 commanded by Lieutenant Colonel David K. Sims responded. Sims was patched into Leonard’s phone call by radio. He was able to overhear Leonard giving his firing clearances to a fire control officer at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.24 Sims’ AC-130 successfully repulsed the attack by knocking out the advancing APC and later setting afire the vacant Bishop residence that was being used as a staging area.

Send in the Marines

As darkness shrouded the shore, the Marine amphibious force came ashore unopposed north of St. George’s at 1900. Golf Company prepared a landing zone for the later arrival of Fox Company by helicopter. The worry on board the Guam now was that the Marines sent to rescue the SEALs would arrive too late.

At around 2215, another AC-130 used its cannon to beat back a group of 15 to 20 Grenadian soldiers who had moved close to the mansion. Lady Esmai Scoon broke down and began to cry. Then, around midnight, the Roman Catholic bishop on the island telephoned Scoon to offer his prayers and support.25 The couple’s courage was restored by his call—and by a gunship that remained overhead until about 0400.

The military situation brightened by dawn on 26 October. During the night, two Marine infantry companies, 13 amtracs, and 5 tanks pushed south on a narrow road leading to the capital, encountering scant opposition. The vanguard of Golf Company arrived at Scoon’s residence just after daybreak. The new arrivals linked up with the 22-man SEAL team and a Scoon party totaling 11 civilians. None of the SEALs were wounded seriously enough to require immediate medical evacuation, but one stoic SEAL suffered a deep gash from a 23-mm cannon shell fragment.26

Scoon and his wife were flown offshore to the Guam at 0857 for a hearty breakfast and tea in Metcalf’s mess. Later, the couple traveled by helicopter to Point Salines, where an impromptu headquarters had been established by Caribbean forces who were supporting U.S. troops. Scoon was presented a batch of four identically worded typed letters, drafted in Barbados.27 The messages were individually addressed to Reagan and the heads of three English-speaking Caribbean islands requesting their intervention. Scoon made one change and then signed the letters, which were back-dated to 24 October.28

Scoon’s 2003 memoir does not specify his “alteration,” but a comparison of the draft with the final version reveals the change that has remained unnoticed since 1983: Scoon deleted the phase “your obedient servant” from the closing of the letter. Evidently, he was concerned that figurative expression could be interpreted literally as conceding his subservience to foreign powers. Scoon was determined to chart his own political course, guided by the Queen, the Grenadian constitution, the Commonwealth tradition, the Eastern Caribbean community, and his personal knowledge of the island’s political players.

“The Governor General must be impartial and he is expected to be above politics,” Scoon declared in his autobiography. In fact, Scoon, showed himself to be a master politician through the entire crisis. He deftly dealt with nearly all the major players in the crisis, except for the Cubans, who shunned him.29

By signing the intervention request and assuming the reins of government in Grenada, Scoon effectively ousted the military junta and ended the revolutionary era. With his signature, he asserted that a “vacuum of authority” then existed on Grenada that allowed him to take executive action on behalf of his nation. He expelled Soviet Bloc diplomats, authorized arrests of the Coard clique, and revived Westminster-style rule on the island. On 9 November 1983, Scoon named a nine-member Advisory Council to serve as an interim administration. Elections were held 3 December 1984 for only the second time since independence in 1974. Based on the vote tally, Scoon invited Herbert A. Blaize, leader of the Grenada National Party, to form a parliamentary government.

On 20 February 1986, President Reagan flew to Grenada for a five-hour visit. He met with Caribbean leaders and spoke to a crowd of 42,000 cheering Grenadians. Scoon hosted Reagan for a private official talk at Government House, the same building that had once been the scene of the day-long siege. There Scoon also was reunited with some familiar faces in the Presidential entourage: four of the SEALs who had rescued him two and a half years earlier.30

1. Larry Speakes and Robert Pack, Speaking Out: The Reagan Presidency from Inside the White House (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1988), 159–60.

2. National Security Decision Directive 110A, National Security Decision Directives (NSDDs), Digital Library, Ronald Reagan Library; Ronald H. Cole, “Operation Urgent Fury, The Planning and Execution of Joint Operations in Grenada, 12 October–2 November 1983” (Washington, DC: Joint History Office, Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1997), 2.

3. “The Maurice Bishop Murder Trial,” The Grenadian Newsletter 14, no. 9 (17 May 1986): 10–12, Digital Library of the Caribbean, Caribbean Newspaper collection.

4. Paul Scoon, Survival for Service: My Experiences as Governor General of Grenada (Oxford, UK: Macmillan Caribbean, 2003), 51–53.

5. Scoon, Survival for Service, 125–26; Geoffrey Howe, foreign secretary, to UK High Commissioner, Bridgetown, “Grenada,” restricted telegram #291, 22 October 1983, Margaret Thatcher Foundation Archives.

6. David Montgomery, Deputy High Commissioner, Bridgetown, to UK Foreign Office, “Grenada: Governor General,” secret telegram #342, 23 October 1983, Margaret Thatcher Foundation Archives. Scoon, Survival for Service, 135.

7. Montgomery, “Grenada: Governor General”; Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 125.

8. Eugenia Charles, Prime Minister of Dominica, as quoted in Deborah H. Strober and Gerald S. Strober, The Reagan Presidency: An Oral History of the Era (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2003), 264. See also Edward Philip George Seaga, The Grenada Intervention: The Inside Story (Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies, 2009), 19; F. A. Hoyos, Tom Adams: A Biography (London: Macmillan Caribbean, 1988), 116; and Lessons Learned as a Result of the U.S. Military Operations in Grenada, House Armed Services Committee, 98th Congress, Second Session, 24 January 1984 (statement of Langhorne A. Motley, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Inter-American Affairs, Department of State), 12.

9. Duane R. Clarridge with Digby Diehl, A Spy for All Seasons: My Life in the CIA (New York: Scribner, 1997), 256–57.

10. Lawrence R. Rossin, “Under Fire in Grenada,” in Duty & Danger: The American Foreign Service in Action, American Foreign Service Association, 1988, 2.

11. Michael J. Durant and Steven Hartov, with Robert L. Johnson, The Night Stalkers: Top Secret Missions of the U.S. Army’s Special Operations Aviation Regiment (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 2006), 24, 26.

12. Robert A. Gormly, Combat Swimmer: Memoirs of a Navy SEAL (New York: Penguin Group, 1998), 196.

13. Dennis Chalker with Kevin Dockery, One Perfect Op (New York: Morrow, 2002), 157–58. Chalker was an enlisted member of the SEAL mansion team.

14. Gormly, Combat Swimmer, 197.

15. Mark Adkin, Urgent Fury: The Battle for Grenada (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books, 1989), 184. Gormly, Combat Swimmer, 197.

16. Michael J. Couvillon, Grenada Grinder: The Complete Story of AC-130H Spectre Gunships in Operation Urgent Fury (Marietta, GA: Deeds Publishing, 2011), 81–82.

17. Joseph Metcalf III, “Decision Making and the Grenada Rescue Operation,” in Ambiguity and Command: Organizational Perspectives on Military Decision Making, James G. Marsh, ed. (Marshfield, MA: Pitman Publishing, 2006), 288.

18. This narrative account of the Marine Cobras at Fort Frederick is drawn from Phil Kukielski, “The Final Flight of Lt. Scharver,” Providence Journal Sunday Magazine, 17 February 1985, and Fred H. Alison, “Operation Urgent Fury: Grenada, 1983,” Fortitude 37, no. 3 (2012): 26–29. Time details come from Dean C. Kallander and James K. Matthews, “Urgent Fury: The United States Air Force and the Grenada Operation, January, 1988,” monograph (declassified 2010), History Office, Air Mobility Command, Scott Air Force Base, ix.

19. Bernard Diederich, “Images from an Unlikely War,” Time, 7 November 1983, 30.

20. Metcalf, “Decision Making and the Grenada Rescue Operation,” 288.

21. Scoon, Survival for Service, 139; Bobby McNabb as quoted in Orr Kelly, Never Fight Fair: Navy SEALs’ Stories of Combat and Adventure (Novato, CA: Presidio Press, 1995), 293. McNabb was another member of the mansion assault team.

22. John J. Fialka, “In Battle for Grenada, Commando Missions Didn’t Go as Planned,” The Wall Street Journal, 15 November 1983; Chalker, One Perfect Op, 164; and Couvillon, Grenada Grinder, 120.

23. Chalker, One Perfect Op, 169; Edgar F. Raines Jr., The Rucksack War: U.S. Army Operational Logistics in Grenada, 1983 (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 2010), 247.

24. Telephone interview by author with Sims, 3 February 2020.

25. Couvillon, Grenada Grinder, 131; Scoon, Survival for Service, 141.

26. Chalker, One Perfect Op, 159.

27. Scoon, Survival for Service, 145. For the text and drafting circumstance of the letter, see Embassy Bridgetown to Secretary of State, “Letter from Grenada Governor General requesting help,” 25 October 1983, Executive Secretariat, National Security Council Cable File, Box 90784, Grenada Cable folder, 25 October 1983 (1), Ronald Reagan Library.

28. For Scoon’s revised, signed version to Reagan, see U.S. Embassy, Bridgetown, secret telegram to Secretary of State, “Letter Requesting US Assistance from Governor-General; Original Received,” 272159Z, 27 October 1983, Bridgetown 06743, Department of State, FOIA release, Case 199804216.

29. Scoon, Survival for Service, 153.

30. Scoon, 232–33.