For four months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan’s forces were virtually unstoppable. Only the 11 December 1941 Wake Atoll landing attempt had not gone according to plan, necessitating a second, reinforced effort two weeks later. However, the 18 April 1942 Doolittle Raid against targets across Japan shattered the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN’s) complacency. In response, the Combined Fleet Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, settled on seizing Midway Atoll as the means to entrap the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s aircraft carriers and defeat them.

Yamamoto had to force his plan past both the skeptical IJN General Staff and the Imperial Japanese Army’s (IJA’s) General Staff, which strongly opposed the Midway operation.1 And staff officers responsible for planning the operation observed that the invasion plan posed “many impossibilities.”2

Seizing Midway Atoll demanded an unprecedented amphibious assault operation. Whereas to that point Japanese Navy and Army amphibious landings mostly had taken place at undefended or lightly defended locations, the small size of Midway’s Sand and Eastern islands meant their entire beachfronts would be defended.

Midway’s fringing coral reef posed two challenges to an amphibious operation. First, even at high tide there was insufficient water to allow landing craft to cross the 110-yard-thick reef. Second, the reef rarely came closer than 220 yards to the beach. This meant a landing force would have to first wade across the coral and then swim or wade through the lagoon to reach the shore. While U.S. Marines would encounter a similar obstacle at the Battle of Tarawa 17 months later, Midway’s reef was a challenge that no modern navy had yet confronted, much less overcome.

In April 1942, Lieutenant Commander Shirō Yonai was assigned to research options for such an assault landing.3 His experiments concluded it was difficult to carry rifles in water as deep as Midway’s lagoon, and that small boats would be needed to ferry sailors or soldiers ashore.4 Later that month, Yonai was posted to Captain Minoru Ōta’s No. 2 Combined Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF—abbreviated to Rikusentai in Japanese). Ōta was a gunnery specialist who had trained at the IJA’s Infantry School and as a lieutenant commander led an SNLF battalion during the 1932 Shanghai Incident. After observing (but not directly participating in) the Combined Fleet’s Midway war games in early May, Yonai concluded:

Higher Headquarters and the Navy General Staff advocated that the occupation of Midway was straightforward, but the No 2 Combined SNLF staff, which actually had to undertake the landing, recognized that it was extremely complicated. The biggest problem was crossing the reef to Eastern and Sand Islands. A corresponding level of casualties was anticipated.5

Preparations

Gradually, both the IJN and IJA General Staffs gave way to Yamamoto’s arguments in favor of the Midway operation, but time was not on Japan’s side. There were six weeks to assemble and train the landing force and deploy it to Midway. The 3,200-strong No. 2 Combined SNLF only had been raised on 1 May and was split between the ports of Kure and Yokosuka. Ōta’s 636-man headquarters included a beachhead exploitation unit, which operated a dozen or more Daihatsu landing craft.6 His combat elements—Captain Yoshitake Yasuda’s Yokosuka No. 5 SNLF and Commander Shōjirō Hayashi’s Kure No. 5 SNLF—were naval infantry, specially reinforced with tanks, flamethrowers, and coastal defense artillery. They were supported by two IJN construction units, known as Setsueitai. These were not military units; they mostly were composed of indentured civilian laborers. The IJA’s contribution to the landing operation, the 2,000-strong Ichiki Detachment, was commanded by Colonel Kiyonao Ichiki and based around an infantry battalion reinforced with an antitank company and an engineer company.7

There also were concerns about the quality of the force’s training. In the Kure No. 5 SNLF, many new recruits failed the swimming test and had to be replaced.8 One of Commander Hayashi’s sailors, Seaman Hisaichi Kawashima, recorded in his diary that embarking in the Argentina Maru was “the first time I have boarded a ship.”9 Partly to offset that inexperience, the Hayashi unit included some veterans from the Shanghai SNLF, and Yasuda’s Yokosuka No. 5 SNLF included many experienced instructors from the IJN’s Gunnery School responsible for SNLF units’ training and doctrine.10 In addition to Ōta’s own experience, Yasuda was one of the IJN’s most experienced SNLF officers and was known as a “Rikusentai God.”11

Before departing Japan, Ōta’s men experimented with different methods for crossing the lagoon. Yasuda’s adjutant, Lieutenant Yasutaka Suzuki, wrote that Midway Atoll’s two islands were surrounded by reef, with the intervening 300–400 meter stretch of waist-deep water. In the case of landing, the landing craft could not cross and advance over the . . . reef tops, which were not covered by even a meter of water. To cross the 300–400 meter gap to the enemy, the SNLF would have to suppress the enemy firepower, while submerged in waist-deep water. It was completely impossible to run in these conditions. In land combat, the most difficult thing is to continue to advance. To do this, they would have to advance while submerged waist-deep in water. Of course, weapons don’t float in water. Ammunition completely sinks. Shooting is completely unnatural. And soaked rations are no good.12

Hayashi’s men experimented with swimming ashore, wearing life jackets or holding lengths of bamboo, firing rifles resting on tire inner tubes, while heavier, crew-served weapons were floated ashore on drum rafts.13 As Ōta and Yonai had feared, none of those methods proved satisfactory.

They settled on using inflatable rubber boats and IJA collapsible assault boats.14 The 16-man engineer assault boats could be broken down into two sections, allowing them to be packed flat for transport. Fully assembled, two of the 23-foot boats could fit into a Daihatsu’s well deck. Nevertheless, doubts remained as to whether this option would work. Captain Toyama Yasumi, Chief of Staff of the 2nd Destroyer Squadron, which would escort the landing force convoy, later recounted:

We were going to approach the south side [of Midway], sending out landing boats as far as the reef. We had many different kinds of landing boats but did not think that many would be able to pass over the reefs. If they got stuck the personnel were supposed to transfer to rubber landing boats. We . . . were not sure of our boats.15

Therefore, the plan was to move the landing force to the reef in Daihatsu, and then to use the collapsible assault boats or rubber boats to cross the lagoon to the beach or for stronger swimmers to swim in.16

Training at Guam and Saipan

When they rendezvoused at Saipan on 20 May, Ōta and Yasuda met with Hayashi for their first joint meeting to discuss the landing plan and their preparatory training. A report of a submarine sighting forced their ships to relocate to Guam the following day.

Relentlessness was the only way to overcome the shortage of training time. Adjutant Suzuki recalled that the training regime was “exhausting. Daihatsu would go out past the reef and then turn about and commence their assault run, halting at the reef line, the sailors would jump into the waist-deep water and wade 400 meters to the shore.”17 This cycle was repeated for the next two days. Seaman Kawashima, commenting on the first nighttime landing practice, wrote that “many troops were wounded.”18 An unidentified sailor from Yasuda’s No.1 Company wrote how the training “seem[ed] like a real war.”19 Another sailor from Kure No. 5 SNLF observed that “one landing craft got stuck on a reef and had to be floated off at high tide.”20 On 23 May, Ōta’s men returned to Saipan for a final night rehearsal. The distance from the reef to the beach at Chalan Kanoa was about 220 yards, but the water was shallow enough to stand up in, leading Hayashi’s quartermaster to question this rehearsal’s value.21

We know less about the Ichiki Detachment’s preparations. Neither the available diaries and memoirs nor the postwar official Senshi Sōsho (War History Series) mentions joint training occurring between the army and navy landing forces. Similarly, there are no further mentions of rubber boats.

Only after the Ichiki Detachment’s convoy rendezvoused with Ōta’s at Saipan on 25 May did the two commanders confer directly. Colonel Ichiki had not been briefed before leaving Japan and did not know the details of the IJN’s plan.22 At Saipan, he learned that Ōta believed the Ichiki Detachment was subordinate to him, and that once Midway was secured, Ichiki was to hand over his defense stores to the navy.Ichiki opposed both those ideas.23

Interservice rivalry to one side, Ichiki was an experienced combat officer in his own right. As a major, he had instigated the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident, which marked the commencement of the war with China. Ichiki, who famously would lead elements of his detachment at Guadalcanal’s Battle of the Tenaru, was not about to be told by a naval officer—even one as experienced as Ōta—how to undertake land combat. To settle the matter, the 2nd Fleet commander, Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondō, agreed that the navy would concede on the matter of the defense stores, but Ichiki would remain under navy command.24

A key vulnerability in the Japanese planning process was the underestimation of the U.S. defenses at Midway. IJN intelligence, based on aerial and submarine reconnaissance, put the Midway garrison at 750 Marines and 500 laborers, with 6 5-inch guns, 12 3-inch antiaircraft guns, 48 .50-caliber and 48 .30-caliber machine guns.25 The last aerial reconnaissance mission over Midway, by one of the IJN’s new, long-ranged Kawanishi H8K Type 2 flying boats, had been on 10 March, but the aircraft was shot down.26 A repeat mission planned for 31 May was canceled when U.S. Navy warships were observed waiting at the flying boats’ refuelling point at French Frigate Shoals.27

Midway’s defenses were significantly stronger than the IJN realized. A total of 107 aircraft were stationed at the Eastern Island airfield. These would have to be destroyed and the airfield suppressed to prevent them from interfering with the landing force’s slow, vulnerable convoy. Colonel Harold Shannon’s Marine Corps garrison had grown to more than 2,000 men, equipped with 8 60-mm mortars; 8 37-mm antiaircraft guns; 24 3-inch antiaircraft guns; four 3-inch, six 5-inch, and four 7-inch naval guns; and a platoon of five M3 Stuart light tanks on Sand Island.28 Most of the Marines were gunners, manning the coastal defense and antiaircraft batteries, but the garrison included four infantry companies. Preparations were such that Sand Island was “surrounded with two double-apron tactical barbed wire barriers, and all installations on both islands were ringed by protective wire.”29 Defensive measures were even more extensive:

380 controlled water mines consisting of a dynamite charge in water pipe with tarred field wire leads were laid along the north beach of Sand Island. . . . Anti-personnel mines consisting of a 6-pound charge of dynamite enclosed on three sides by nails were laid around the entire beach perimeter of the island. The more probable landing beaches had two such strips of mines which could be set off either electrically or by firing rifles or machine guns at the dynamite charge on the inboard side of the mine. . . . 1500 contact anti-tank mines containing a 5-pound charge of dynamite and capable of being exploded by a 40-pound pressure were laid along the beaches most likely to be used for the landing of tanks. . . . Molotov cocktails: 310 “Victory” cocktails were prepared and distributed to gun positions and to the infantry for use against tanks.30

As they prepared to depart for Midway, the SNLF sailors had mixed feelings.31 Seaman First Class Gi’ichi Andō, from Yokosuka No. 5 SNLF, confided in his diary on 28 May: “5 o’clock left Saipan for Midway Island. Praying for a successful landing.”32

Pre-Landing Plans, Results

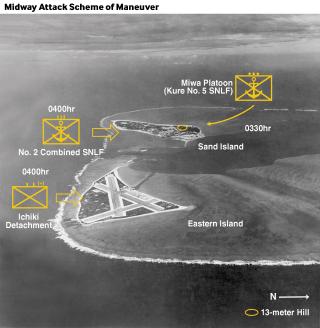

Ahead of the landing, three preparatory attacks would be made. First, Special Duty Midshipman Shinzō Miumi’s 50-man platoon from Kure No. 5 SNLF’s antiaircraft gun company would seize nearby Kure Atoll the night before the Midway landing.33 This would allow the IJN to establish a seaplane base there to support the Midway landing and to conduct antisubmarine patrols.34

Next, IJN carrier aircraft were to establish air superiority by destroying Midway’s air forces either on the ground or in the air.35 Their secondary aim was to target the airfield and its facilities and the atoll’s air defenses.36 But as the 108-plane Japanese strike later demonstrated, Eastern Island’s three airstrips proved difficult targets to neutralize.

Attacking aircraft set ablaze Sand Island’s oil tanks and destroyed Eastern Island’s powerhouse and command post.37 Nevertheless, the damage to Midway was not overwhelming—four defenders were killed and ten wounded and power was out, but otherwise the defenses were more or less intact and the airfield remained operable.38 Accentuating that point, some of the Midway-based bombers and torpedo planes that had attacked the Japanese carriers, as well as the atoll’s surviving fighters, landed safely after the IJN carrier-plane raid on the airstrips. While available Japanese aircraft were being prepared for a second strike against the atoll, the naval battle commenced in earnest, leading to the loss of all four Japanese carriers by the following morning.

Had events transpired otherwise, before the landing, naval gunfire from the light cruiser Jintsū and two destroyers could have helped suppress U.S. defenses. Seaplanes would have directed the ships’ fire using a 100-meter-interval gridded map of the islands that had been prepared for the landing, but only if Midway’s air forces were no longer a threat.39

It remains unclear whether a gunnery duel would have developed, as had happened during the first Japanese attempt to seize Wake Atoll. The IJN had not identified Midway’s two 7-inch batteries. Unless these were silenced, the landing force’s transports would be at great risk. The Japanese plan called for the transports to drift to halt lines directly south of the atoll, as close as 4,400 yards to Sand Island’s 7-inch battery.40 Even at that short distance, the Daihatsu landing craft would need an hour to complete a ship-to-shore landing cycle. If the transports were forced to stand farther off, the time between the initial assault and second landing waves would also increase, slowing the buildup of Japanese combat power on the beaches, jeopardizing the cover of darkness, and reducing the operation’s chances of success.

The Assault Plan

From the anchorage, the Ichiki Detachment and SNLF assault waves would assemble on their transports’ decks in the dim moonlight. At around 0300, the order would be given to embark into the landing craft, and the men would clamber down nets or Jacob’s ladders into the Daihatsu waiting below. The landing craft would then form two lines abreast: One group would take the Ichiki Detachment to a point opposite Eastern Island’s central southern shore. The other would take Ōta’s No. 2 Combined SNLF to land opposite Sand Island’s Frigate Point, with Hayashi’s men on the left (western) flank, and Yasuda’s on the right (eastern). At these locations, the reef-to-beach gap narrowed to between 160 and 330 yards.

Meanwhile, the third preparatory operation would be under way. Kure No. 5 SNLF’s Antiaircraft Company commander, Lieutenant Yūnoshin Miwa, was to lead a feint, landing against Sand Island’s northwestern corner where the Marines had made their heaviest defensive preparations:

My duty was to lead a platoon [about 50 men] . . . to seize the 13 meter heights and raise the Hinomaru Flag there, about 30 minutes prior to the landing by the SNLF. I recall that the Main Landing Force was to land at 0400 hrs (local time). So we would have to land in darkness.41

Moving at their eight-knot full speed, the Daihatsu carrying the main assault forces would take around 15 to 20 minutes to reach the outer reef. Even with the low tide, a dim surf line made the reef line discernible. At the reef, the landing craft would lower their bow ramps to allow the assault landing wave to disembark. Sixteen-man teams of soldiers and sailors would then haul their 440-pound collapsible assault boats out of their landing craft’s well-deck and across the coral. The Ichiki Detachment and Ōta’s SNLFs would each have sufficient assault boats to carry about two companies at one time.42

Once they reached water deep enough to float the boats, the soldiers and sailors would need about three to five minutes to paddle across the lagoon. This was the U.S. garrison’s primary killing ground. The landing force would be under fire from small arms, machine guns, mortars, some of the antiaircraft guns, and, as they drew closer to the shore, hand grenades.

Once ashore, the Japanese assault waves would have to clear the barbed wire and improvised mines and fight their way inland. Dense vegetation would channel groups of men onto the islands’ few cleared pathways and crushed-coral roads. On Sand Island, the Marine garrison planned to counterattack with its tank platoon. Against the Stuart tanks, the SNLF could rely on only flamethrowers or grenades. Their own antitank guns, antiaircraft guns, and tanks could not be landed until the atoll had been sufficiently cleared to allow landing craft to enter either of the atoll’s two channels through the reef to land these heavy weapons directly onto the beach.

Eastern Island presented its own challenges. If Ichiki’s men got off the beach, they would encounter a second killing ground created by the 1,750-yard east-west airstrip that ran close to the southern shore. Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka, commander of the 2nd Destroyer Squadron, later wrote of Ichiki’s plan:

I became aware of his tough personality and his style of combat leadership. In the case of the Midway operation, his forces were to be lightly equipped with five rounds of rifle ammunition and two days’ rations. They would leave their ships and board Daihatsu which [would] take them to the reef at once, where they would transfer into collapsible boats to cross the lagoon, and then occupy the airstrip in one swoop by bayonet charge. He planned that weapons would only be fired after that was achieved.43

Whether Ichiki’s plan would have worked, or whether Ōta’s men would have been successful, remains a matter for conjecture. The available records demonstrate that Midway Atoll’s fringing reef and the strength of the U.S. defenses meant that the odds were stacked against the Japanese.

1. Japan National Institute for Defense Studies, War History Department, Senshi Soˉsho [War History Series], vol. 14, Army Operations on the South Pacific, vol. 1: Commencement of Port Moresby—Guadalcanal Operations (Tokyo: Asagumo Newspapers, 1968), 130.

2. Chikataka Nakajima, Rengoˉ Kantai Sakusenshitsu Kara Mita Taiheiyoˉ Sensoˉ [The Pacific War, as Seen from the Combined Fleet Operations Room] (Tokyo: Koˉjinsha, 1988), 47.

3. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, Midway Sea Battle (Tokyo: Asagumo Newspapers, 1968), 182.

4. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 182.

5. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 183, 185.

6. Chikanori Moji, Sora to Umi no Hate de [At the Ends of Sky and Sea] (Tokyo: Mainichi Shimbun-sha, 1978), 87; Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 62, Naval Operations on the Central Pacific Ocean Front, vol. 2 (Tokyo: Asagumo Newspapers, 1973), 65.

7. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 14, 292.

8. Moji, Sora to Umi no Hate de, 59.

9. Allied Translator and Interpreter Service Current Translations (hereinafter AWM55), item no. 3/2, entry for 14 May 1942, No. 280, 2, Australian War Memorial.

10. Moji, Sora to Umi no Hate de, 59; Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 170, 182.

11. Kuninori Kimura, Yasuda Rikusentai Shirei Den [A Biography of the Special Naval Landing Force Commander Yasuda] (Tokyo: Koˉjinsha, 1992), 240.

12. Yasutaka Suzuki, Ike to Shi to [Life and Death] (Toyonaka, Japan: self-pub., 1987), 9.

13. Moji, Sora to Umi no Hate de, 66–68.

14. Moji, Sora to Umi no Hate de, 69.

15. United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) Interrogation Nav. No. 60, CAPT Yasumi Toyama, IJN, 1 October 1945, 250, quoted in Lt. Col. Robert D. Heinl Jr., USMC, Marines at Midway (Washington, DC: Historical Section, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1948), 22.

16. Moji, Sora to Umi no Hate de, 69.

17. Suzuki, Ike to Shi to, 13.

18. AWM55, item no. 3/2, entry for 20 May 1942.

19. AWM55, item no. 3/1, extracts from diary of No. 5 Special Landing Party Yasuda 1 Chutai 2 Shotai 4 Buntai (Yokosuka No. 5 SNLF, No. 1 Company, No. 2 Platoon) Warisota—16 November 1942, entry for 23 May 1942, No.145.

20. AWM54, item no. 423/4/28, Translations of Captured Documents, 9 October 1942, Captured Document No. 56, Diary of Hikita Shigeto of Kure Japan, Conscripted Seaman No. 18928, Kure No. 5 Special Landing Force.

21. Moji, Sora to Umi no Hate de, 68.

22. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 184, 187.

23. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 187.

24. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 188.

25. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 65.

26. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 38, Naval Operations on the Central Pacific Ocean Front, vol. 1 (Tokyo: Asagumo Newspapers, 1973), 508.

27. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 220.

28. Commander-in-Chief United States Pacific Fleet, Operation Plan No. 29-42, 27 May 1942, at midway1942.com/docs/usn_doc_00.shtml, 5; Frank O. Hough, Verle E. Ludwig, and Henry I. Shaw, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol. 1, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal (Washington, DC: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1958), 219.

29. Hough, Ludwig, and Shaw, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, 220.

30. Col. Harold D. Shannon, USMC, Report of action on morning of 4 June, 1942, and night of 4–5 June, 1942, Headquarters Sixth Defense Battalion, Fleet Marine Force, 13 June 1942, midway1942.ru/docs/usn_doc_16.shtml, 6–7.

31. AWM55, item no. 3/2 Allied Translator and Interpreter Service Current Translations No. 280, 5, entry for 16 May 1942.

32. AWM55 item no. 3/1, entry for 28 May 1942.

33. Moji, Sora to Umi no Hate de, 66–68.

34. Patrol Boat No. 35 War Diary, 1–30 June 1942, Japan Centre for Asian Historical Records, Ref. C08030623900, 0372; Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 172–73.

35. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 423.

36. Ibid.

37. Hough, Ludwig, and Shaw, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, 221.

38. Shannon, Report of action, 7.

39. 2nd Destroyer Division War Diary Combat Report (2), no. 2, 1 May to 7 August 1942, Japan Centre for Asian Historical Records, ref. C08030095000, folios 1433–34.

40. 2nd Destroyer Division War Diary Combat Report, folio 2.

41. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 43, 186.

42. Important Documents File Related to Operations, vol. 2, no. 6, January to December 1942, at Japan Centre for Asian Historical Records, Ref. C13071074300, 172, identifies the Ichiki Detachment as having 30 assault boats, while Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 14, 293, indicates the number was 40. In AWM55, No. 280, Item No. 3/2, 9, entry for 21 May 1942, Seaman Kawashima noted that he and others “went to receive 24 boats,” suggesting a total of 48 such craft for the No. 2 Combined SNLF.

43. Senshi Soˉsho, vol. 14, 296.