As with so many forgotten U.S. Coast Guard stories of heroism, bravery, and courage, the story of Michael Augustine Healy is unknown to most Americans—and even many service members. Healy’s career tied him to the taming of Alaska, America’s last frontier, and made him likely the most interesting and controversial captain in Coast Guard history.

Child of the South

Born in 1839 on a plantation near Macon, Georgia, Healy was the son of a white plantation owner and a slave. Had he remained in Georgia, Healy’s part-African racial makeup could have led to enslavement according to the laws at that time. To escape this situation, Healy’s father sent Michael and his siblings away to be raised and educated in the North.

The Healy children were sent to the Holy Cross Academy (later known as the College of the Holy Cross) in Worcester, Massachusetts. Devout Catholics, several of Healy’s siblings became ranking members in the Catholic Church hierarchy, including brothers James (the Bishop of Portland, Maine) and Patrick (president of Georgetown University) and his sister Eliza Healy, who became Mother Superior overseeing a number Catholic convents and schools. The Healy children, in the parlance of the times, “passed for white” and never divulged their racial background to others.

Unlike his siblings, Healy’s calling was the sea. In 1855, at the age of 15, he completed his education at Holy Cross and signed on to a merchant ship. Over the next ten years, he “came up through the hawse pipe” with the enlisted ranks on commercial vessels to become a merchant ship officer. In 1865, he applied for a commission in the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, predecessor to the Coast Guard. During this period, and later in his career, Healy developed a penchant for drinking and earned the nickname “Hell Roarin’ Mike” due to his loud and boisterous behavior in the bars. He did not relish or encourage this nickname.

A Historic First—Unbeknownst at the Time

In March 1865, just a month before his assassination, President Abraham Lincoln signed Healy’s commission. With that signature, Healy became the nation’s first commissioned officer of African-American descent. He also was the first to command a U.S. vessel, first to achieve every commissioned officer rank from third lieutenant to senior captain (a rank in the late 1800s equivalent to today’s flag rank), and first to command ships in North and South American waters, including the Bering Sea and the Arctic.

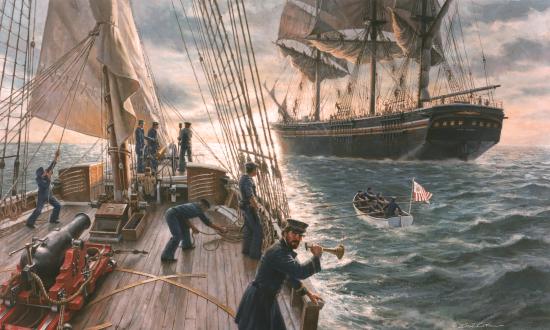

Two years after receiving his commission, Healy served as navigation officer on board the 110-foot revenue cutter Reliance on her voyage from the East Coast around Cape Horn to San Francisco. The trip began in August 1867 and included eight brutal days of gale-force winds and mountainous seas as the topsail schooner slugged her way around “the Horn.” This trip cemented a long friendship between Healy and Captain John Henriques, the Reliance’s commanding officer. A few months after the Reliance arrived in San Francisco, the Treasury Department ordered her to the newly acquired territory of Alaska. In October 1868, Henriques and Healy sailed to Sitka with the Reliance, one of the first cutters to serve in Alaskan waters and the first one to enforce U.S. laws there.

From the Reliance, Healy and Henriques transferred to the West Coast cutter Wayanda, and four months later, they transferred to the steam sailing cutter Lincoln. Healy returned with Henriques to the East Coast after their tour in the Lincoln ended.

During these shared cutter assignments, Healy learned a great deal from Henriques, probably the service’s most experienced officer at that time. In 1874, Henriques received orders to ferry the new cutter Rush around Cape Horn to San Francisco and selected Lieutenant Healy as his executive officer. After the delivery, Henriques and Healy returned to the East Coast; however, in 1880, Healy went back to the West Coast to serve out the rest of his illustrious career.

North to Alaska

Alaska’s vast maritime and coastal frontier required the support of the service’s law enforcement, humanitarian, and search-and-rescue capabilities, so revenue cutters patrolled coastal waters as well as the Bering Sea. During the late 1800s, American maritime interests chased valuable resources such as seals and whales into icebound waters. In addition, as U.S. shipping began to operate into the winter months, the duties of the Revenue Cutter Service multiplied in frozen areas previously considered un-navigable in wintertime.

During her 1880 Bering Sea Patrol, the revenue cutter Corwin undertook a search for the missing Arctic exploration vessel USS Jeannette. It was the service’s first Arctic rescue expedition. On board the Corwin, Healy served as executive officer under famed revenue cutter captain Calvin Hooper. The 1880 cruise established the annual Bering Sea Patrol as a primary mission of West Coast revenue cutters; however, no trace was found of the missing ship. It was later learned that the Jeannette had been crushed in the ice with the loss of 21 crew members.

In 1882, Healy assumed command of the venerable Corwin. In the fall, an event occurred that haunted him the rest of his career. The U.S. Navy command in Alaska believed the native Alaskans located in the village of Angoon to be in a state of rebellion and ordered Healy to shell the village, devastating the settlement and killing and wounding villagers. In the eyes of native Alaskans, this event tarnished Healy’s career and remains to this day a controversial issue in Alaskan history.

In spite of the Angoon incident, Healy grew to become a larger-than-life character. In 1883, he was promoted to captain; he later described his command philosophy:

. . . when I am in charge of a vessel, I think I always command. I think that I am there to command, and I do command, and I take all the responsibility and all the risks, and the hardships that my officers would call upon me to take. I do not steer by any man’s compass but my own.

Healy wrote two Bering Sea Patrol cruise reports published by the Government Printing Office that became popular books. In 1894, the New York Sun claimed Healy was “a good deal more distinguished [a] person in the waters of the far Northwest than any president of the United States.” In an article, the newspaper asked, “‘Who is the greatest man in America?’ and the answer is, ‘Why, Mike Healy.’”

A Maritime ‘Wild West’

Many have heard of the sheriffs and marshals of the “Old West.” Men such as Wyatt Earp upheld the law in places like Tombstone, Arizona. While law enforcement officials of the Old West laid down the law in a town or stretch of land, Captain Healy laid down the law for the Territory of Alaska and the Bering Sea, an expanse of water and land roughly the size of the lower 48 states. Moreover, while sheriffs in the Old West used a horse and a gun for law enforcement, Healy had an armed vessel, which cruised the endless waters of the eastern Pacific, North Pacific, Siberia, and Arctic.

Few know of Alaska’s dangerous maritime frontier of the late 1800s—a place far worse than the fabled “Wild West.” There, Healy made his name contending not only with misfits and criminals, but also with deadly sub-zero temperatures and ship-sinking ice, using a wooden vessel far less capable than today’s icebreakers. In addition to the ice, there were heavy seas and high winds as well as rocks and reefs ready to disembowel a wooden ship. Healy described the conditions in his log: “This is a miserable country to cruise about in—miserably surveyed and full of hidden rocks and reefs not down on the charts.”

In April 1886, Healy took command of the revenue cutter Bear after she arrived at her new home port of San Francisco. It was like a second marriage for Healy (he had married in 1865). Owing to his reputation and successful missions, he commanded the Bear on the annual Bering Sea Patrol for the next ten years. During the warmer spring and summer months, each one of the patrols covered 20,000 miles cruising the islands and coastal regions of the Bering Sea.

Conditions on the Bering Sea Patrol were harsh, dangerous, stressful, and, at times, deadly—a fact demonstrated by the remains of Bear crew members left behind at Dutch Harbor, Alaska’s lonely cemetery. Late in his career, Healy described the hardships of this thankless but important job:

to stand for forty hours on the bridge of the Bear, wet, cold, and hungry, hemmed in by impenetrable masses of fog, tortured by uncertainty, and the good ship plunging and contending with ice seas in an unknown ocean.

‘Furs Are Gold!’

In 1867, when Alaska became a U.S. territory, one of the revenue cutters’ primary duties was protecting endangered fur seals from poachers. This duty was the genesis of the Coast Guard’s modern LMR (living marine resources) mission. Under Captain Healy, the Bear patrolled the waters of the Pribilof Islands, enforcing seal-hunting regulations and seizing poaching vessels. Regarding seal poachers, Healy later stated, “Those operators would gladly cut your throat and sink your ship with all hands aboard for the sake of furs. Furs are gold in Alaska!” Seal hunting patrols proved the cutters’ law enforcement value, and in 1908, the Revenue Cutter Service took responsibility for enforcing all of Alaska’s game laws.

Under Healy, one of the Bear’s best-known missions was saving lives at sea, but the revenue cutter also preserved the lives of those struggling to survive on land. Native Alaskans had been whalers and fishermen for centuries when the territory came under U.S. control. As outside whaling and fishing vessels depleted Alaskan waters, these food sources declined dramatically, causing large-scale malnutrition and starvation among native Alaskans. To help them, Healy tried to convince authorities that Siberian reindeer could be introduced to Alaska, stating, “The introduction of deer seems to be the solution of three vital questions of existence in this country—food, clothing and transportation.” By 1890, Healy had hatched a plan to get reindeer to Alaska.

Reindeer, Rescues, and Other Missions

In 1891, to test the reindeer’s ability to travel by sea, Healy shipped 16 deer and hundreds of bags of feed-moss from Siberia to the Aleutian Islands. The experiment proved a success, and won over government officials in Alaska and Washington, D.C. In 1892, Healy brought over the first shipment of reindeer to Alaska’s Seward Peninsula and established a receiving station at Port Clarence. Over the course of the 1890s, cutters transported thousands of reindeer to Alaska. By 1930, Alaska’s domesticated deer herds totaled 600,000 head, with 13,000 native Alaskans relying on them for basic nutrition.

Under Healy’s command, the Bear’s humanitarian efforts not only included the care of native Alaskan communities and the rescue of seafaring people; the cutter also combated illegal liquor distribution used to exploit native peoples. They referred to the Bear as Omiak puck pechuck tonika, meaning “the fire canoe with no whiskey.” The Bear’s humanitarian support of Alaska was assistance on a large scale, but the cutter also helped individuals on the maritime frontier. As one Revenue Cutter Service historian wrote, “In assisting private persons, neither class, race, nor creed made any difference to the Bear; degree of stress was the sole controlling factor.”

For generations, no roads or railroads existed in Alaska, so cutters were the only federal presence in the territory. Under Healy, the Bear became not just a multimission vessel, but also an interagency asset providing support for all federal agencies in Alaska. For example, on Healy’s 1891 cruise, the Bear:

1. Secured witnesses for a murder case

2. Ferried reindeer from Siberia to Alaska

3. Sailed Alaska’s governor on a tour of coastal islands

4. Shipped a U.S. Geological Survey team to Mt. St. Elias

5. Carried lumber and supplies to build schools in

as far north as the Arctic Circle

6. Delivered schoolteachers to their assignments

7. Carried mail for the U.S. Postal Service

8. Enforced seal hunting laws in the Pribilof Islands

9. Supported a U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey team

10. Provided medical relief to native populations

11. Served life-saving and rescue missions

12. Enforced all federal laws in the territory.

Through it all, Healy’s African-American heritage remained unknown to his shipmates, peers, and the Revenue Cutter Service. No evidence exists that anyone besides his wife and siblings ever knew the details of Healy’s roots. It was not until the 1970s that researchers discovered Healy’s racial background.

A Remarkable Career, a Lasting Legacy

By the mid-1890s, Healy had served ten years on the Bering Sea Patrol. Ironically, while one of the Bear’s missions was to interdict smuggling of illegal liquor to native Alaskans, Healy’s own drinking problem had grown worse in his later years. In 1896, the service relieved Healy of command, dropped him to the bottom of the captain’s list, and placed him for four years on “Awaiting Orders,” similar to unpaid leave. The service later reinstated Healy, and he served on board a number of cutters before retiring in 1903 as the third-most senior officer in the service.

Captain Michael Healy made a lasting contribution to American history. He was the first man of African-American heritage to receive a U.S. sea service commission and first to command a federal ship. As a powerful law enforcement officer in a lawless maritime frontier, he helped shape the history of Alaska. During his time in the territory, he explored and policed, protected, nurtured, defended, and helped preserve the humans and animals that survived in that forbidding land. Today, he is the namesake for the Coast Guard’s medium icebreaker USCGC Healy (WAGB-20).

In 1904, physically spent, Healy died at age 65. His oceangoing career had spanned 50 grueling years. He was laid to rest at Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery near San Francisco, a stone’s throw from the final resting place of his land-based peer—Wyatt Earp. To this day, Captain Healy is remembered for his invaluable contributions to the service, the Alaska Territory, and the nation.