If ever an engagement encapsulated both the human and inhumane elements of naval warfare, it was the Battle of North Cape. Fought in the dark, freezing, storm-tossed seas of the Arctic Ocean, spanning a less than festive Christmastime, the clash was the last encounter between capital ships in World War II’s European theater and a battle whose outcome hinged as much on the differing philosophies and mentalities of the belligerents as on the big guns deployed by either side. Eighty years on, Rear Admiral Erich Bey remains the most enigmatic and controversial protagonist. Was he to blame for the German battle cruiser Scharnhorst’s failed late-December 1943 sortie and ultimate destruction, or was he merely a convenient scapegoat for the Kriegsmarine’s strategic and structural failings and to safeguard Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz’s ambitions?

In Far Northern Waters

The origins of the Scharnhorst’s final, fateful operation can be traced back 12 months to New Year’s Eve 1942 in those same northern waters blanketed in boreal darkness. In the Battle of the Barents Sea, a superior German force consisting of the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper and the pocket battleship Lützow broke off engaging an Allied Arctic convoy when faced with its escorting destroyers and light cruisers (see “The Battle That Scuttled Hitler’s Surface Fleet,” December 2022, p. 9). The timing could hardly have been worse; Operation Winter Storm, the Wehrmacht’s attempt to relieve the entrapped 6th Army at Stalingrad, had failed barely a week before.

Adolf Hitler was apoplectic. He subjected Grand Admiral Erich Raeder to a tirade disparaging the Navy’s lack of worth. Despite later attempts at rapprochement, Raeder resigned as head of the Kriegsmarine at the end of January 1943. He was replaced by Dönitz, the mastermind behind the U-boat campaign in the Atlantic, who initially supported the Führer’s “unalterable resolve” that the navy’s big ships should be withdrawn and scrapped, with their guns and crews redeployed. However, after consulting Raeder, Dönitz made an abrupt volte-face, the original plans were mitigated, and the Scharnhorst, among others, was reprieved.

In March 1943, the Scharnhorst joined the battleship Tirpitz and two flotillas of destroyers at Altafjord near Norway’s northern tip as part of the Northern Task Force. Although an ever-present threat, the task force’s activities were limited to training exercises, except for the largely propagandist attack on the island of Spitzbergen in early September 1943. Later that month, British midget submarines immobilized the Tirpitz with explosive charges, and Churchill agreed to the resumption of Arctic convoys. He also offered the recently vacated position of First Sea Lord to Admiral Bruce Fraser, commander of the Home Fleet. Fraser demurred, citing his lack of combat experience, but prophetically responded: “I haven’t even fought a battle yet. If one day I should sink the Scharnhorst I might feel differently.”

From Destroyerman to Force Commander

On 8 November 1943, a week before that first convoy sailed from its Scottish haven, Northern Task Force commander Vice Admiral Oskar Kummetz left for Germany on extended sick leave. He was replaced temporarily by Rear Admiral Bey, who was known by his nickname “Achmed.” A physically big man, his reputation had been forged in small ships.

A fellow officer once remarked of Bey that “a soft heart beat behind a rather forbidding exterior.” He was born on 28 March 1898 and joined the Imperial German Navy at 18, serving in destroyers during the Great War and interwar years. As a commander, he led the 4th Destroyer Flotilla in minelaying operations off England’s North Sea coast in late 1939 and then into action at Narvik in April 1940. He received the Knight’s Cross and promotion to captain the following month and, after further operations along the British coast, earned attention for coordinating the destroyer screen for the audacious February 1942 Channel Dash of the Scharnhorst; her sister, the Gneisenau; and various other Kriegsmarine ships from Brest to German ports. The reflective glory of these exploits enhanced Bey’s standing, and on 1 March 1943 he was promoted to rear admiral.

Despite the promotion, Bey remained a destroyerman after reassignment to the Northern Task Force, but he clearly impressed his superiors sufficiently to gain the appointment, on the recommendation of Fleet Admiral Otto Schniewind, to succeed Kummetz. Bey’s infamous quip, “The last time I was aboard a capital ship it was as a cadet,” did little to assuage fears among the Scharnhorst’s crew that this was a man metaphorically out of his depth.

Challenging Assignment

Bey’s situation in November/December 1943 wasn’t helped by vague guidance from overbearing superiors, poor communications, and a depleted retinue.

Ostensibly, he was in operational command, but in practice Schniewind and Dönitz pulled the strings. Advice and orders were full of rhetoric but often short on details, and early strategic prerequisites for authorizing a sortie were conveniently ignored when political imperatives took precedence. Despite deplorable weather, the intelligence service and much maligned Luftwaffe would provide valuable information before and throughout the forthcoming action, but deep-seated interservice mistrust meant that it was ignored, ill-used, delayed, or simply not passed to Bey.

Given Bey’s inexperience in flag command, it would have made sense to surround him with experienced officers, yet the opposite happened. Accompanying Kummetz back to Germany were key staff members who would have been invaluable in the upcoming operation.

On 20 November 1943, Schniewind’s naval staff at Kiel issued its directive on fleet operations for the forthcoming winter. With the Tirpitz incapacitated, the document cautiously stated, “Operations must be compatible with our small strength, and the use of Scharnhorst in the winter is to be considered.” That small strength now consisted of the Scharnhorst, the five ships of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla, and 20 U-boats based in the Norwegian ports of Bergen and Trondheim. The 6th Destroyer Flotilla had been sent back to Germany three days earlier. Schniewind also demanded a “fair assurance of success” based on accurate weather forecasting and knowledge of enemy dispositions before endorsing any action. With reduced Luftwaffe reconnaissance and a depleted naval force, such opportunities appeared slim.

Two days later, and just two weeks after taking command of the Northern Task Force, Bey responded. Echoing Kummetz’s parting advice, he requested (but was denied) the reinstatement of the 6th Flotilla and advocated sorties by the destroyers alone until the Tirpitz was repaired. Bey finished his report with a somewhat fey statement: “Despite our weaknesses, we have had many favorable opportunities in this war and experience shows that we can hope that luck is on our side.”

In the penultimate week of 1943, all these considerations became irrelevant. Since November, dozens of Allied merchantmen had passed unscathed between Scotland and the northern Russian ports of Murmansk or Archangel. The pressure on Dönitz was mounting.

The Opposing Plans

Home Fleet Commander-in-Chief Fraser also sensed it, later commenting, “With the safe arrival of [Convoy] JW 55A I felt very strongly that Scharnhorst would come out and endeavor to attack JW 55B.” In fact, Fraser planned to lure the Scharnhorst out in the belief that Murmansk-bound Convoy JW 55B was easy prey, defended only by the destroyers, minesweepers, and corvettes of its escort groups.

As the convoy approached the most perilous section of the voyage, its escorts would be augmented by the cruisers of Force 1—HMS Belfast, Norfolk, and Sheffield—which were under the command of Vice Admiral Robert “Nutty” Burnett and had set out from Murmansk. Simultaneously, Force 2—Fraser’s flagship, the battleship Duke of York; the light cruiser Jamaica; and four destroyers—would distantly shadow Convoy JW 55B, closing in once assured that the Scharnhorst had taken the bait.

On 19 December, Dönitz attended a conference at the Wolfsschanze, Hitler’s Eastern Front headquarters where Raeder had been berated less than a year earlier. With the Führer’s patience running thin and the grand admiral’s status as the heroic leader of the wolf packs in jeopardy, Dönitz made a clear commitment “that Scharnhorst and the destroyers of the task force will attack the next Allied convoy headed from England for Russia via the northern route, if a successful operation seems assured.”

Despite the caveat, Schniewind and Bey knew the implications. Dönitz had staked his reputation on retaining some heavy units of the surface fleet and realistically “a successful operation” was required, whatever the odds. Even as the grand admiral was leaving Hitler’s headquarters the following day, Convoy JW 55B departed Loch Ewe, setting in motion Fraser’s trap.

The second element of Fraser’s plan occurred at 1045 on 22 December, when a Luftwaffe reconnaissance plane sighted the convoy (at first mistakenly reported as an Allied invasion force). Details were relayed via Kiel to Bey, who happened to be on board the Scharnhorst on a pre-Christmas visit.

Prompted by an expectant Dönitz and the convoy’s relentless eastward passage, a seemingly reluctant Fleet Admiral Schniewind drafted orders for Operation Ostfront (as the German sortie was codenamed) on Christmas Eve. The grand admiral approved the plan on Christmas morning.

Conflicting Instructions from Above

The Scharnhorst, with Captain Fritz Hintze in command, sailed at 1900 on Christmas Day, but Operation Ostfront almost was aborted before she and the 4th Flotilla destroyers reached open water. A Force 8 gale was blowing in the Barents Sea, driving snow showers and mountainous seas from the southwest. Bey knew more than anyone that such conditions were at the very limit of his destroyers’ seaworthiness, adding his own reservations to those of Narvik-based Captain Rudolf Peters, who commanded the seven U-boats of Gruppe Eisenbart, and members of Schniewind’s staff. The fleet admiral duly messaged Dönitz, advocating that the sortie be canceled.

Nevertheless, after midnight Bey received confirmation from the grand admiral to continue as planned. Even this signal contained ambiguity and contradiction. It stated, “Engagement not to be broken off till full success achieved,” yet in the following paragraph added, “Disengagement at own discretion, and automatically if heavy forces encountered.” In a nominal show of support, Dönitz rather ominously concluded, “I am confident of your offensive spirit.”

Erich Bey now faced the defining moment of his career, fully aware that none of Schniewind’s earlier prerequisites (accurate meteorological forecast, precise knowledge of enemy strength and disposition, and the element of surprise) had been met. Bey and others (notably, staff officers in Narvik and Kiel) still suspected the presence of a latent covering force. They also were completely unaware that another convoy, Britain-bound RA 55A, and its escorting cruisers, Force 1, were entering the vicinity from the east.

As for surprise, Fraser held all the aces. First, the Admiralty judiciously had forwarded to him decrypted German signals intelligence (Ultra). From Luftwaffe and U-boat radio transmissions to the timing of the Scharnhorst’s departure, Fraser had a clearer picture of German movements than Bey.

Then there was radar. Old hands in both navies were skeptical of the “new” technology, but whereas the Royal Navy adopted, enhanced, and used it extensively, the Kriegsmarine underdeveloped and underused radar, mainly for fear of detection by superior Allied passive detection equipment. In practice, this meant the Scharnhorst relied almost entirely on visual range finding for her big guns, limiting the ship’s most effective operational winter window in far northern latitudes to the brief twilight in the middle of the day. Radar and its use would prove crucial in the ensuing action.

Remaining Questions

In the early hours of 26 December, thousands of young men on both sides battled the elements as they converged in the inhospitable waters south of Bear Island, which is northwest of Norway’s North Cape. At 0700, Bey reduced speed to 12 knots and deployed the 4th Destroyer Flotilla’s five ships in a scouting formation, line abreast ten miles ahead of the battle cruiser. Naval commanders and armchair admirals have debated Bey’s subsequent performance ever since, Dönitz being among the first and most critical.

Three key questions stand out:

• Why did the Scharnhorst’s accompanying destroyers become detached from the battle cruiser?

• Why did Bey not fully engage the cruisers of Force 1 to break through to the convoy?

• Why, having decided to break off the action, did Bey take a direct southerly course back to Norway, allowing his pursuers to shadow and ultimately destroy the Scharnhorst?

Once the destroyers were arrayed, the Scharnhorst changed course to port, followed at 0820 by an obtuse turn back to the north. Our understanding of Bey’s reasoning remains pure supposition, although the likelihood is he reacted to two intercepted U-boat reports. Why Bey ordered Captain Rolf Johannesson, commanding the 4th Destroyer Flotilla, to make the first change (to port) but not the second (to the north) remains a mystery. The consensus is that Bey either forgot or the order was never delivered.

Perhaps, however, Bey was covering his options. Around 0300, six hours after receiving Bey’s concerns about the weather, Schniewind had signaled, “If destroyers cannot keep sea, possibility of Scharnhorst completing task alone using mercantile warfare tactics should be considered.” Although inexperienced in his new role, Bey had earned commendations from his peers and even Dönitz for his tactical astuteness. Unencumbered by the destroyers and with the Scharnhorst’s speed and stability, he might have been following the scent of the U-boat reports, while the destroyers, laboring through the gale, combed to the southwest. Ironically, had he maintained the original course Bey probably would have intercepted the convoy.

Dönitz’s Sharp Criticisms

At 0926 a star shell fired from HMS Belfast turned darkness to light, illuminating the Scharnhorst in a pink-hued glow. Unbeknown to Bey, Burnett’s Force 1 had been shadowing his flagship by radar, and within moments the heavy cruiser Norfolk’s 8-inch guns opened fire. Reacting immediately and effectively, Captain Hintze ordered the battle cruiser’s helm over 30 degrees to port, increased speed to 24 knots, and laid a smoke screen to obscure her from her pursuers. Although hit by the third of the Norfolk’s salvos, within 20 minutes the Scharnhorst was out of gun and radar range.

Contrary to Dönitz’s later statement that “tactical coordination” between the German battle-group elements then ceased to exist, Bey signaled Johannesson to establish his whereabouts and redeploy the destroyers with the intention of attacking the convoy in a pincer movement. Unfortunately, Johannesson was too late to come to the Scharnhorst’s aid later in the battle, and the destroyers took no further part in the day’s proceedings.

Perhaps the most unjust of Dönitz’s criticisms was his implication of cowardice. The grand admiral reflected, “When contact had been established in the morning, the ensuing gun battle should have been fought to its conclusion.” Rather melodramatically, he concluded that once the Scharnhorst had destroyed the cruisers, the convoy would have been offered up “like ripe fruit.” Smearing Bey’s character was not only underhanded, but also contrary to his own orders and the Kriegsmarine’s modus operandi.

In fact, many of the surface fleet’s supposed failings stemmed from Hitler’s personal prejudices. “On land I am a hero but at sea I am a coward,” he once confided to his commanders, and this sentiment was reflected in his “Battle Instructions for the German Navy,” published as part of a broader strategy document in May 1939. The following quote is particularly pertinent: “The task of naval warfare in extra-territorial waters is war on merchant shipping. Combat action even against inferior naval forces is not an aim in itself and is therefore not to be sought.” As Dönitz succinctly put it, the need to stay afloat prevented the ships from fighting.

The Hunter Is Hunted Down

Almost precisely three hours after the first clash of the battle, Bey experienced déjà vu. The Scharnhorst was probing in the twilight, intent on attacking the convoy from the northeast, when another star shell exploded above at 1221. This time her gun crews responded quickly, and in the ensuing exchange she caused extensive damage to the Norfolk and scored hits on the Belfast and Sheffield. Twenty minutes after it had begun, the action ended with the Scharnhorst veering off to the southeast.

This second encounter convinced Bey to head for home. He signaled to Narvik: “Engaged by several enemy. Radar directed fire from heavy units.” The Scharnhorst twice had been foiled by a foe that seemed to know her every move; the hunter had become the hunted.

The southerly course Bey adopted back to the battle cruiser’s Norwegian lair was certainly the quickest, but with a beam sea, Burnett’s depleted Force 1 could comfortably maintain radar contact over the horizon. Had Bey taken a southwesterly course, the Scharnhorst’s superior speed and seakeeping probably would have shaken off her shadowers, but perhaps he intuitively knew a greater danger lay in that direction.

Although mentally and physically exhausted, Bey perhaps afforded himself a wry smile when his repeated warnings about a covering force were finally confirmed around 1330. A German BV-138 Sea Dragon flying boat had reported sighting Fraser’s Force 2 at 1010 that morning; the crucial ensuing three-hour delay alerting Bey was systematic of poor German communications that day.

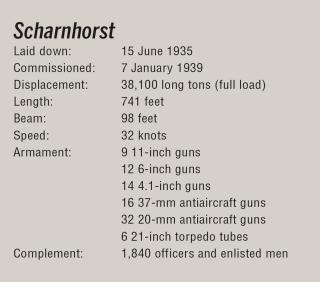

With a certain inevitability, the afternoon lull was broken when a star shell burst overhead at 1647. Salvos from the Duke of York and Jamaica rained down, almost immediately rendering the battle cruiser’s 11-inch triple “Anton” turret inoperable, but the Scharnhorst fought back bravely, and in the ensuing encounter, Hintze and Bey skillfully maneuvered their ship until her much-vaunted 32-knot speed had allowed her to draw away from her pursuers. It seemed she had escaped, but then a chance shell, fired at extreme range from the Duke of York at 1820 punctured her armor belt and exploded in her starboard machinery space. The ship’s lucky reputation finally deserted her.

Despite superhuman efforts by the engine room crew, the ship’s speed dropped, and she was caught and subjected to multiple torpedo attacks and point-blank gunfire. At about 1940, with the hulk finally sinking by the bow, Bey and Hintze gave the order to abandon ship and, according to one of the just 36 survivors, calmly shook hands with each member of the bridge team. Neither the admiral nor the captain survived.

I leave the final word to Bey’s nemesis, Admiral Fraser, who lamented to Duke of York officers later that day: “Gentlemen, the battle against Scharnhorst has ended in victory for us. I hope that if any of you are ever called upon to lead a ship into action against an opponent many times superior, you will command your ship as gallantly as Scharnhorst was commanded today.”

Sources:

CDR D. L. Kauffman, USN, “German Naval Strategy in World War II,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 80, no. 1 (January 1954).

Angus Konstam, The Battle of North Cape: The Death Ride of the Scharnhorst, 1943 (Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Books Ltd., 2009).

John Winton, The Death of the Scharnhorst (Chichester, UK: Antony Bird Publications Limited, and New York: Hippocrene Books Inc. 1983).