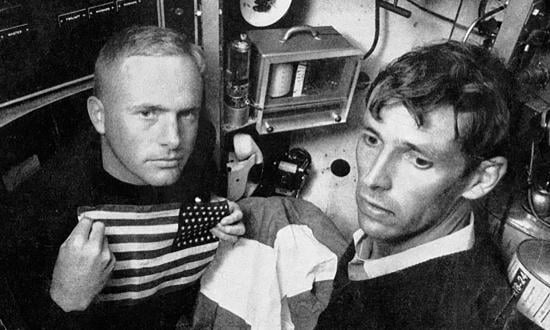

When the U.S. Navy’s bathyscaphe Trieste descended to the deepest known floor of the world ocean in 1960, the mission never came close to garnering the press attention drawn by the exploration of space. Captain Don Walsh, U.S. Navy (Retired) had gone down 35,840 feet to the Challenger Deep in the Marianas Trench in the Trieste with Swiss explorer Jacques Piccard. The global focus still went mostly to the space program and Mercury astronauts Alan Shepard and John Glenn, loosely bolstered later in the decade in this country by the TV series Star Trek, in which the fictional Captain James Kirk in the starship Enterprise set out “To boldly go where no man has gone before.” Then-Lieutenant Walsh and Piccard were no less bold and no one before them had gone where they went. They simply went deep, under the same intense pressure, both physical and mental, and not up, into the gravity-free weightlessness of space.

In the wake of the 18 June implosion of the OceanGate Inc. tourist submersible Titan, and after an entire month of intense media coverage, we spoke with Captain Walsh and James P. Delgado, two pioneer deep-divers, both having been to the wreck of the ill-fated ocean liner Titanic, the destination of the recreational excursion that went so awry and imploded, killing all hands.

Walsh: ‘Not If, But When’

For this report, Captain Walsh, author for decades of the popular Naval Institute Proceedings column “Oceans,” shared his insights on what happened to the OceanGate vessel and why.

“Put crudely,” Walsh said, “it was not if, but when this would happen. Over 70 years, the number of fatalities from deep dives was six—three Americans and three Japanese. That’s a pretty good safety record. The Titan loss nearly doubled that number.”

He added, “There are dedicated tourist submarines—they do call them ‘submarines’—that carry paying passengers down to about 100–150 feet. They have been around since 1985, when the Canadian company Atlantis Submarines put its first one into service. Since that time, 14 have gone into service to take several million tourists into the sea with no loss of life or serious injury. All subs were classed and built in accordance with the rules. That’s safety!”

As background for his commentary on the “recent event,” Walsh recalled traveling to the OceanGate factory in 2018 to observe, in person, the submersible under construction:

“I was very skeptical of what they were doing. Stockton Rush, [the company’s owner, who perished in the implosion] asked me to be an adviser, and I turned him down, telling him that ‘I’m uncomfortable with the fact that you’re taking such a risk. Based on lessons learned over a half-century, you cannot get insurance for your operation if you’re not properly classed.’ The classification societies inspect and approve the submersibles’ design, construction, operations, and maintenance. OceanGate wanted nothing to do with the societies. No understanding of submersible safety was evident.”

Walsh lamented that “the loss of even one submersible has a significant effect on the entire manned-submersible community. This was a rogue operation from the start. Since the early 1960s, manned-submersible operations have required an on-scene backup system to provide aid in case of emergencies. This operation had no such support.”

As for the impact of Rush and his company’s disregard for required protocols, Walsh pulls no punches: “Some people are going to have even more egg on their face, because they didn’t perceive what was going on. If they did, they didn’t listen. In my view, it was low-level fraud. They figured out a way to get around all the regulations.”

By all published accounts, the mission was doomed from the start. The loss of the carbon-fiber, titanium-, and steel-built vessel, controlled by a Sony PlayStation joystick, came as no surprise. How and why the vessel and her crew perished at the site of the Titanic’s remains continues to be a question posed that, a month later, continues to garner international attention, notably because the answers keep changing.

Delgado: ‘Incredibly Saddened’

For this report we also called on James P. Delgado, along with Captain Walsh is a bona fide veteran of exploring the depths of the sea, for his assessment of what really happened, why it took so long to abandon the search for any human remains, and the “hardest part,” Delgado lamented: notifying next-of-kin of the devastating loss of human lives.

Delgado is a longtime contributor to Naval Institute publications, distinguished scholar, author or editor of 30 books, and perhaps best known worldwide as host, for six seasons each, of two popular National Geographic TV series, The Sea Hunters and Drain the Oceans. He served in executive positions with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Vancouver, (BC) Maritime Museum, and the National Park Service and since 2017 has been affiliated with the global-reaching archaeological firm SEARCH Inc., where he currently serves as a senior vice president.

The day after the disaster, Delgado surmised to us that international efforts led by the U.S. Coast Guard to make contact proved futile because the Titan had imploded, a devastating inward event that essentially disintegrates everything enveloped by the hull of the submersible. All this questions the wisdom of taking “tourist trips” to shipwrecks in the deep ocean in the first place. While James Cameron, director of the movie “Titanic” and a deep-dive veteran himself, was the go-to expert in the disaster’s aftermath, nothing was heard from Delgado and Walsh, until now.

“I was not surprised but incredibly saddened,” Delgado said. “What was also evident, just from the initial reporting, and if you know anything about that community—those who do submersible and deep-ocean work—there were things implicit but not understood by the public.”

He continued, “Reports that communication was lost an hour and 40 minutes into the dive, as well as the location of the submersible, were troubling. With that type of failure came a simultaneous seismic event. That said to me that the sub had suffered an implosion. In a very sad way, with that assumption came a sense of relief that they weren’t trapped on the bottom. Having been trapped on the bottom myself under the stern of the Titanic, one of the longest 20 minutes of my life, I held out hope, however slim, that they we would soon be drifting on the surface, or were on the thermocline somewhere, which seemed unlikely.”

According to Delgado, “James Cameron said it best: ‘They were dead before they knew they were dead,’ because an implosion is so fast and so violent. The description of the debris was not only where a number of us thought it would be, but also an indication of just how violent it was.”

The Tourist Submersible

“Deep-dive tourism uses a different type of submersible from those used for exploration. I read how some comments were focused on how ‘it’s something rich people can do, and that the rest of us now had to pay for it,’ meaning the search,” Delgado said. “In the timeless tradition of the sea, regardless of how somebody gets into trouble, everybody on the surface or in the water turns to, to assist in the rescue. I’m upset over the circumstances in which people died who need not have died.”

Regarding the flurry of negative commentary amid the ongoing search, Delgado observed, “The comments suggested to me that there apparently was a lot of armchair-admiraling going on. To the contrary, I’m pleased that forces from the United States and Canada stood to. I also have the utmost respect for the ‘Coasties’ and the private vessels that continued to search, despite the information—that an hour and 45 minutes into the dive, their location was lost and that a seismic event had been detected. For something to be described in that way certainly reinforced the thought that this was an implosion.”

Delgado recalled, “Having been in the position of alerting families of those who are lost, I can tell you it’s a terrible responsibility to call the next-of-kin when the loss is still raw. It never goes away, and I know what that feels like, having dived on the wrecks of sunken ships lost decades ago [including the sunken ships at Pearl Harbor, among others too numerous to name]. The descendants are no less sad and distressed. Relatively few, thank goodness, know what that feels like. In 2017, before I left NOAA, I had to console the brother of a person lost. It’s a huge burden to break the news.”

We asked Delgado for his assessment of the press coverage of the Titan tragedy. “It’s a clear example of people who know very little about this, trying to enter an arcane world. And then there were the jokes and unkind remarks, not in the press coverage necessarily, but in the general response. It’s why I don’t look at the comment sections of media stories.”

What drove many of the presumed experts to distraction was the constant reference to the OceanGate Titan as a submarine. “It was not,” Delgado clarifies, “it was a submersible that maneuvers up and down only. Once it reaches the desired spot on or near the bottom, it can hover there but is not designed to move laterally. To move upward, it’s ‘drop and go’ to release ballast and start to move upward.”

Going Forward

“The deep ocean, the inner space, does not attract as much attention as outer space. But this incident will generate a lot of second-guessing. The question is, should we continue to go into the deep? The simple answer is, yes. It’s more than the last frontier. This is something that is of vital importance. It’s as well far more than simply science. The ocean is, after all, the source of the oxygen we breathe.”

Regarding the Titanic wreck site specifically, Delgado recalled, “After we did our work on the Titanic in 2010, we talked about the changes to the site since 1985, including all the garbage there. Expeditions in 2003 and 2004 also had brought back images of modern, post-discovery garbage littering the site. In the middle of the Atlantic, because so many had come to see the wreck, there was now all sorts of trash. Not one place where I’ve been in the ocean has been free of human refuse on the bottom. But this was more. Those sites are, in their own way, museums. And they literally force rewrites of history. But they also deserve respect and study. The amount of collaborative science is incredible.”

Delgado concluded, “In a 2000 article in Archaeology magazine, I contended that there is a place for tourism dives. The ships are museums on the sea floor. I hope that this tragedy will not serve as an excuse to curtail ventures into the deep. After all the investigations, what needs to happen now is issuing some basic requirements—such as a government or insurers’ inspection of submersibles.”