The U.S. Navy faced a new and very different set of challenges in protecting President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who loved the sea, spending more days afloat than any U.S. president. It was not uncommon for new sailor-in-chief and his crew of amateur sailors to take to the sea in a small sailboat, sometimes for days at a time.

He would skillfully—and with a great deal of delight—evade his Navy and Secret Service guards, sailing his schooner, the Amberjack II, into secluded coves and narrow reaches where Navy and Coast Guard vessels—FDR called them “our wagging tail”—could not follow. In what may seem like a shocking lapse in security, by today’s standards, Navy and security guards were not permitted to travel on board FDR’s boats, but were relegated to trailing behind, trying desperately to keep up with the elusive President.

FDR once disappeared into the fog, cutting himself and the crew off from their escorts for several hours. During another sail, Roosevelt led the Navy to think he was going to navigate around Cape Ann when he suddenly decided to take a shortcut through the narrow and crooked Annisquam Canal. The Navy vessels could not make the six-mile trip through the narrow canal and were forced to race around the cape to meet Roosevelt on the other side.

Only three months after being sworn in as the United States’ 32nd president, Roosevelt was at the helm of a 45-foot twin-masted schooner on his way to a ten-day sailing vacation along the New England coast. His June 1933 400-mile trip began in Marion, Massachusetts, and ended at Campobello, New Brunswick, where FDR and his family maintained a summer home.

The trip marked the first time Secret Service agents and Navy commanders experienced sailing with—or tailing behind—the new President, a sport that became commonplace during Roosevelt’s 12 years in the White House. Presidential guards traded in their suits and ties for oilskins and life jackets as they did their best to keep up with America’s new sailor-President.

On this trip, the weather turned decidedly bad, with eight-foot seas tossing the President’s boat around for five hours. FDR, remaining at the wheel the entire time, decided to make an impromptu stop at Nantucket Island, 30 miles off the coast of Massachusetts. The President became concerned after newspapermen in nearby press boats became, as he put it, “white around the gills,” showing unmistakable signs of seasickness. Navy destroyers and Coast Guard cutters did their best to keep up.

The entire town of Nantucket, once the whaling capital of the world, turned out to greet the nation’s new President. Enterprising islanders rowed people out for 25 cents a head to get a closer look at Roosevelt and his schooner, the Amberjack II, moored in the harbor. Town officials rowed out to see the president, pleading with him to come ashore. Roosevelt resisted this and all other efforts to get him to leave his boat during the cruise, noting that this was his vacation and that he did not “intend to set foot on dry land for two weeks.” He kept that promise.

But for 16-year-old Phyllis Norcross it was a day she would never forget. Phyllis and three of her Academy Hill classmates got out of school early in honor of the President’s visit. The girls ran down to Steamboat Wharf, where a raft used to unload seaplane passengers was located. Tied to the raft was a dinghy, which the girls “borrowed” and rowed out to see the President.

When they arrived, no one was on deck. Finally, after what seemed like ages, Jimmy Roosevelt, the President’s son, appeared. “Where’s your old man?” Phyllis yelled. “He’s having lunch,” replied Jimmy. The girls pleaded with Jimmy to have FDR at least pop his head out of the hatchway.

Jimmy eventually complied, and President Roosevelt appeared. “What are you having for lunch?” Phyllis asked. “Ham and eggs,” replied the President. “Would you like some?” Before they could take the President up on his invitation, a Navy patrol boat appeared and warned the girls to return the dinghy to the dock or face arrest. “We rowed back as fast as we could,” the Nantucket girl remembered, but she never tired of telling everyone that the President of the United States invited her to lunch!

At 0545 the next day, the President gave the order to weigh anchor, and the Amberjack II was under way, quietly gliding out of the harbor, again catching Navy and Coast Guard vessels by surprise. This was the beginning of what would be 12 years at sea for FDR and some immense challenges for those charged with keeping the United States' President safe.

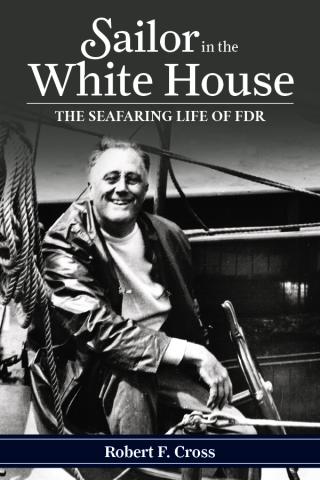

Robert F. Cross is the author of Sailor in the White House: The Seafaring Life of FDR, published by Naval Institute Press. Sailor in the White House offers more stories about America’s greatest seafaring President and includes photographs of FDR at sea. For more information about this author, please visit his website here . Cross is on Twitter @robertfcross.

To read Michael Beschloss’ New York Times article on Sailor in the White House click here. займ онлайн