Penniless, bereft of options, devoid of opportunities—such are the usual conditions that steer a soul toward a life of outlawry. So it was for any who dared set forth (most likely in a stolen vessel) to seek an ill-gotten fortune as a pirate on the high seas. But among that infamous roster of cutthroats from the golden age of piracy, there was one distinctly different from the rest—an heir to landed wealth and prosperity, a man with a wife and children and a plantation on Barbados, a person knowing no hunger or neediness: Stede Bonnet.

Why this individual, with virtually no knowledge of seamanship, decided to cast aside his privileged existence to sail off on a desperate criminal career remains a mystery. Bonnet “was a Gentleman of good Reputation . . . , was Master of a plentiful Fortune, and had the Advantage of a liberal Education,” noted the 18th-century pirate chronicler Charles Johnson. “He had the least Temptation of any Man to follow such a Course of Life, from the Condition of his Circumstances.”

Whatever spurred him, in the spring of 1717 Bonnet purchased a sloop, named her the Revenge, fitted her out with ten guns and 70 hired men, and stole away from Barbados in the dead of night. In matters nautical, he was thoroughly out of his element, but he had a well-seasoned quartermaster who kept the sails tight and aimed right, and before long, the Revenge was plundering prizes all along the Atlantic coast from Long Island to the Carolinas. The notoriety of “the Gentleman Pirate” quickly grew, and he soon fell in with that fearsome alpha wolf of the brethren of the black flag: Edward Thatch (aka Teach), Blackbeard himself.

They formed a rogues’ alliance that was snakebitten from the get-go. Blackbeard sidelined his new partner, took charge of both ships, then disappeared with the hoard of pirate bounty they had amassed, leaving the double-crossed Bonnet high and dry.

But he rebounded, blazed a fresh trail of maritime larceny, and by late summer 1718, he and his crew were hiding out with a couple prize sloops in tow in the Cape Fear River, where they careened the leaking, barnacle-encrusted Revenge, now renamed the Royal James, for overdue repairs. Word got to nearby Charles Town, South Carolina, which had suffered more than its share of piratical depredations. Colonel William Rhett, the provincial receiver-general, offered to smoke out the pirates. The governor granted him a commission, and on 14 September 1718, Rhett set out with two ships, 16 guns, and 132 men.

They sighted the pirate masts on the evening of 26 September. Bonnet and co. sighted Rhett’s approaching masts as well; hoping they were merchantmen ripe for the plucking, they scouted in canoes and then realized they had a fight on their hands. Bonnet decided to shoot his way out and make a dash for open water.

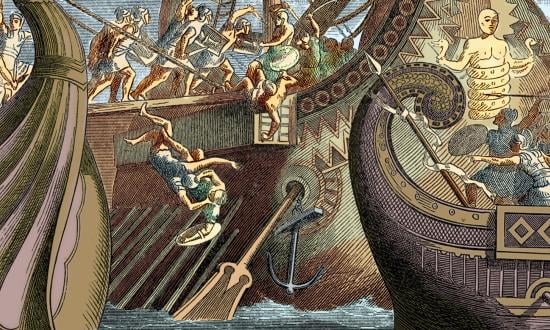

At dawn, he hoisted the Jolly Roger, sailed into range, and commenced blasting with cannon and musket fire. Rhett’s ships fired back and got moving, but they ran aground. Bonnet, dodging their return volley, headed too close to shore, and now the Royal James ran aground as well. And what followed holds a unique spot in the annals of naval warfare—a battle in which both combatants were stuck on the sand for the entire engagement. Thus, the Battle of Cape Fear River, as it is remembered, has an alternate name as well: “the Battle of the Sandbars.”

For five hours, the Royal James and Rhett’s flagship, the Henry, unloaded on each other relentlessly. The pirate vessel held the advantage: She had grounded at an angle with her side tilting upward in the face of the enemy, whereas the Henry was trapped in a down-sloping angle, rendering her deck a wide-open target for the jeering pirates firing from behind the bulwark of their up-tilted hull. But the battle turned with the tide: Rhett got the Henry free from the sandbar first; he maneuvered her into deeper water and closed in for the kill.

Bonnet sensed the bloodbath looming and waved a flag of truce. Rhett boarded and realized he had nabbed the notorious Gentleman Pirate. Taken into custody, Bonnet subsequently managed to escape. His freedom would be short-lived, though. The authorities ran him down on Sullivan’s Island and hauled him to Charles Town, where he was tried and sentenced to death.

The pirates’ heyday was ending. Blackbeard’s luck had run out as well; by late November, his head was dangling from a bowsprit. And on 10 December 1718, Stede Bonnet did the hangman’s dance. He had yearned to live like a pirate. And in the end, he died like one too.

Sources:

Court of Vice-Admiralty, South Carolina, The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other Pirates (London: Benjamin Cowse, 1719), iii–vi.

CAPT Charles Johnson, A General History of the Pyrates, from their Rise and Settlement in the Island of Providence, to the Present Time, 2nd ed. (London: T. Warner, 1724), 91–112.

Norman Pendered, Stede Bonnet: Gentleman Pirate (Manteo, NC: Times Printing, 1977).