When Dan Gallery came up with the idea of capturing a German U-boat during World War II, he was met with considerable skepticism. But he never was one to let others dissuade him from bold and unusual actions. Despite the obstacles and potential for failure, then-Captain Gallery—in command of the USS Guadalcanal (CVE-60) and antisubmarine Task Group 21.12—carefully planned and executed one of the most audacious operations in naval history—an event that is today enshrined in one of two dioramas in the U.S. Naval Academy’s Memorial Hall. It was the first time since the War of 1812 that the U.S. Navy had captured a foreign combatant vessel, was accomplished with no loss of American lives, earned one participant a Medal of Honor, and nearly cost Gallery a court-martial and an early end to a career that ultimately lasted from 1917 to 1960!

On the face of it, the capture of U-505 was a very good thing indeed, but there were other factors involved that could have had dire ramifications. Gallery’s plan worked so well that not only did the Germans not have time to scuttle the boat, but they also were unable to destroy any of the sensitive equipment on board, including an Enigma coding machine with its variable rotors intact, as well as the accompanying code books.

Had the Germans learned of the capture, they most certainly would have changed their codes and cipher wheels, negating all the successful code-breaking that the British and the Americans had enjoyed for most of the war to that point and leaving them suddenly in the proverbial dark at a critical time in the conflict. Only by keeping the capture secret could this be prevented, and, despite the large number of people in TG 21.12 who had participated, Gallery was able to convince them all to keep it quiet. It must have been excruciating for so many sailors—who love few things more than a good sea story, especially one like this—to maintain their silence until the Battle of the Atlantic was won. Instead of a court-martial, Gallery eventually was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal.

Had Dan Gallery done nothing else in his Navy career, he would be remembered for his capture of U-505, an extraordinary example of archetypal thinking and innovation. But this was only one of his many achievements, and not the only time that he would find himself in the crosshairs of controversy.

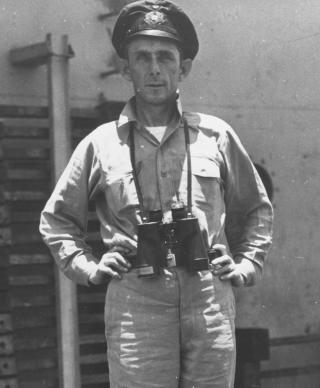

Daniel V. Gallery entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1917 at 16 and graduated in only three years—in time to compete as a wrestler in the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, Belgium. He was an early naval aviator who was a winner at the National Air Races in the late 1930s, flying a specially configured Devastator torpedo plane. His World War II service included command of the Fleet Air Base in Reykjavik, Iceland, before taking command of the Guadalcanal and achieving everlasting fame.

After the war, then–Rear Admiral Gallery once again defied the odds by launching a captured German V-2 rocket from the deck of one of the Navy’s premier postwar aircraft carriers, risking damage to the ship while challenging the Air Force’s presumed dominance in the realm of then-burgeoning atomic warfare.

In 1949, Gallery joined the so-called Revolt of the Admirals, writing a series of articles for The Saturday Evening Post that criticized Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson’s plans to reduce the Navy’s roles in the developing Cold War with the Soviets, including scrapping the carrier fleet and having the Army absorb the Marine Corps. Gallery’s articles pulled no punches and likely cost him a third star.

In the 1960s, Marcus Aurelius Arnheiter was relieved for cause for questionable actions while in command of a destroyer escort off Vietnam, and Lloyd Bucher sparked controversy as commanding officer of the USS Pueblo (AGER-2) when she was captured by North Korea. Both matters were contentious among the Navy officer corps, causing much polarization and unhappiness, but Gallery characteristically refused to stand clear and weighed in heavily.

Gallery’s writing was not confined to inflammatory articles. He wrote a series of lighthearted novels whose main protagonist was a boatswain’s mate known as “Cap’n Fatso” that revealed his engaging sense of humor. He also wrote a more serious Cold War novel (The Brink; Doubleday, 1968) and a number of nonfiction works dealing with the U-505 capture and the Pueblo incident.

In 1999, C. Herbert Gilliland and Robert Shenk wrote a biography titled Admiral Dan Gallery: The Life and Wit of a Navy Original (Naval Institute Press). In his foreword to the book, Herman Wouk, famed author of The Caine Mutiny (Doubleday, 1951) and The Winds of War (Little, Brown and Company, 1971), effectively portrayed this unique man:

There are dark shadows in his story, as well as brilliant episodes of ingenuity and heroism. . . . Take him for all in all, he was a credit to the United States Navy, to his country, and to his faith; a decidedly human gentleman with human failings, more than balanced by rare willpower, brainpower, and humor.