On 16 December 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt stood on the deck of the presidential yacht Mayflower and watched the U.S. Navy’s Great White Fleet steam out of Hampton Roads at the beginning of its landmark globe-circling cruise. This was perhaps the culminating moment of Roosevelt’s career. An unapologetic navalist, Roosevelt had long promoted the idea of a strong battle fleet capable of meeting any enemy as an equal. As Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the McKinley administration, and now in his second term as President of the United States, Roosevelt had used his unrivaled oratory skills, progressive zeal, and boundless energy to reshape the U.S. Navy into one he believed to be “second to none.”

The Great White Fleet was the living embodiment of American genius and the “big stick” Roosevelt needed to place the United States among the major powers of the world. As a practical matter, it would act as a deterrent to Japanese expansion in the Pacific by demonstrating the ability of the U.S. Navy to transit a battle fleet from the U.S. East Coast to the West Coast.1

Yet, as the fleet sailed away, many of its officers knew that it harbored a dirty secret—one that would be revealed to the world within a few short weeks when an illustrated article in McClure’s Magazine hit the newsstands just before that Christmas. The article described the numerous technological shortcomings in the ships of the fleet and unfavorably compared it to the Imperial Russian Baltic Fleet destroyed at Tsushima Strait—claiming in effect that the Great White Fleet was more of a Great White Elephant.

After the great enthusiasm generated by the sailing of the fleet, the article hit the public like a bombshell, triggering outrage, spurring a Senate investigation, and causing great embarrassment to the Roosevelt administration.

Auspicious Beginnings

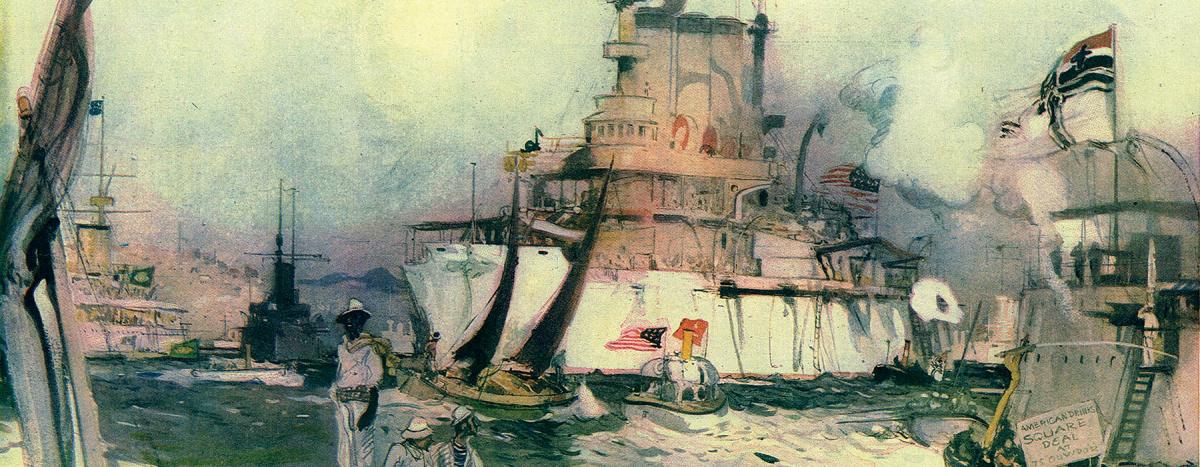

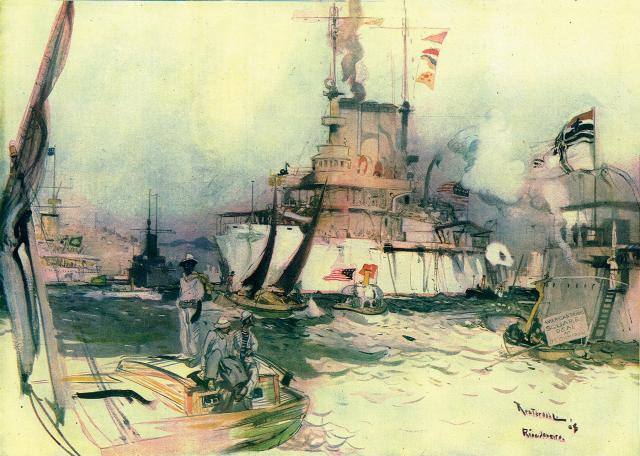

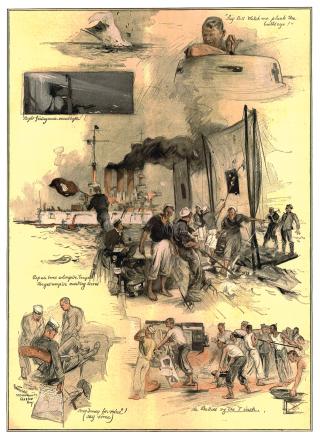

The irony was that the article’s author, at the invitation of the President himself, was sailing with the fleet on board the armored cruiser USS Minnesota. He was Henry (Henrik) Reuterdahl, a Swedish-born journalist and naval artist whose previous work had done much to generate public support for the U.S. Navy. Born in Malmo, Sweden, in 1870, Reuterdahl was part of a large and distinguished family; he was the namesake of his uncle, the Archbishop of Uppsala. Indulging in his talent for art, Reuterdahl left technical college to pursue a career as a freelance artist and illustrator. His work appeared in many popular weekly magazines, one of which sent him to Chicago to report on the Columbian Exposition of 1893.

The wonders of American art, architecture, and industry on display so clearly seduced the 23-year-old Reuterdahl that he decided to make the United States his home. His love of the U.S. Navy also may date from this time, as the exposition featured the USS Illinois, a full-scale replica of an Indiana-class battleship.2

Reuterdahl was a talented illustrator and soon was hired by several American magazines. Assigned to cover the U.S. Navy during the Spanish-American War, he generated magazine illustrations that glorified the defeat of the Spanish at the hands of the plucky Americans. The style of his work was modern and impressionistic, and his colorful illustrations glamorized and popularized the U.S. Navy. Reuterdahl painted not only dramatic scenes of warships and naval battles, but also the more mundane tasks of shipboard life. His sympathies were clearly with the men of the fleet; his art was much more realistic and technical when depicting their activities. His work found favor with President Roosevelt and many naval officers, including Lieutenant Commander William S. Sims, who, as Inspector of Target Practice, commissioned Reuterdahl to create trophies for gunnery excellence.3 They became lifelong friends.

Reuterdahl had acquired enough knowledge of naval affairs that by 1903 he was the U.S. editor of Jane’s All the World’s Fighting Ships. He was passionate about the Navy and Roosevelt’s vision for its future. Reuterdahl’s ideas were in sync with those of the progressive reformers of his generation, embodied in kindred spirits such as Sims and his coterie of “Young Turks,” the officers of that generation who looked to reform the U.S. Navy.

Defects Dangerously Ignored

The Navy’s bureau system of administration became a target of the reformers when the many deficiencies in warship design and construction made themselves manifest in the new fleet that was being built at great expense to the American taxpayer. Sims had become aware of these during his time on board the newly built battleship USS Kentucky during her cruise to the China Station in late 1900. In particular, the design of the 13-inch guns of the main battery came in for criticism. The Bureau of Ordnance had designed them without coordinating with the Bureau of Construction and Repair, which designed the turrets. The guns were designed with their trunnions too close to the breech, so to facilitate the elevation of the barrel very large openings in the turret face were required, which Sims reckoned would allow enemy shells to pass through easily.

The Kearsarge-Kentucky class also featured an 8-inch battery superimposed on top of the main fore and aft turrets. The design of the ammunition hoists to serve both sets of guns required the interior of the barbette be open all the way down to the handling room at the bottom, with the magazines exposed. If an enemy shell entered the large gun openings, the resulting explosion would threaten the entire ship.

Another design defect that was well known to line officers was the fact that when U.S. warships were fully loaded for sea duty they displaced more tonnage than specified in the original design, resulting in their armor belts being mostly submerged below the waterline. Adding insult to injury, when combined with the low freeboard that was a characteristic of many U.S. battleships, the secondary battery was unusable in a seaway, and the turrets shipped large amounts of water breaking over the bow. One officer in the Great White Fleet remarked that the battleships were essentially very large, slow armored cruisers.4

These design “features” would be carried forward into the latest Virginia class of battleships as well. Taken individually, these design decisions were justified by the bureaus as necessary to maximize firepower while staying within the weight and displacement limits imposed by Congress. The designers, however, failed to see the problems in the whole ensemble, while the line officers who would have to fight these ships stayed mum rather than buck the system and risk their careers. Sims, however, was not such a officer, and he wrote long letters to the Bureaus of Construction and Ordnance describing his findings in detail. Sims’ critiques were sent to the bureaus, where they languished.5 In the meantime, the bureaus continued to design and build new ships to their own standards with little input from line officers.

Tragedy Sparks Action

The design limitations placed on U.S. warship construction originated in Congress, mostly from the Senate Naval Committee, chaired by Senator Eugene Hale of Maine. Hale and many of his colleagues were deeply conservative and opposed the progressive movement in general—and particularly the rise of what they considered unbridled imperialism emanating from the Roosevelt administration.6 They were disturbed by the seemingly limitless demands for ever bigger, more expensive battleships and placed limits on the size of ships to keep costs down.

Hale also opposed the reforms in the administration of the Navy that Sims and the insurgents sought. By the summer of 1907, these reform efforts had reached an impasse. Then, on 15 July 1907, there was another in a series of horrific turret accidents, this time on board the USS Georgia during target practice off Cape Cod. A flareback from the superimposed 8-inch guns of the aft turret sent flaming debris onto the powder bags of one of the main guns below, causing the smokeless powder to ignite, killing ten men, including the turret commander, Lieutenant Caspar Goodrich Jr. Although the guns were equipped with an anti-flareback gas ejection system, it was not enough to overcome the fatal flaws in the open turret design. Only the quick action of the men in the magazine handling room at the base of the turret kept the flames from destroying the entire ship.

This may have been the last straw. The newspapers once more had a field day reporting the gruesome details to a shocked public. Sims decided then to make an appeal to the ultimate decision-maker, the American taxpayer, essentially betting his career on the public’s innate good sense and disgust at yet another deadly naval mishap.

Using the analysis of the defects in naval design and administration supplied by his friend Sims, Reuterdahl had penned an article in 1904 titled “A Plea for Naval Efficiency.” At that time, however, things seemed to be going the way Sims liked, and he had prevailed on Reuterdahl not to publish it, but now Sims judged that the time was indeed ripe and encouraged him to proceed. This he did, approaching McClure’s Magazine, well known for its investigative muckraking reporting, with the idea. The publisher, S. S. McClure, jumped at the chance, and Reuterdahl’s revised article, retitled “The Needs of Our Navy,” appeared on the newsstands in late December 1907—as the Great White Fleet was entering its first port of call at Port of Spain, Trinidad.

Pull-No-Punches Article Makes Waves

The article was written in a style easily understood by the layman and was lavishly illustrated to clearly demonstrate the points being made. Reuterdahl recounted how, for the past ten years, the United States had built 20 first-class battleships at a cost of $145 million, all with the same defect of having the bulk of their armor belts submerged below the waterline:

No other nation of the world has ever made this fundamental mistake, except in the case of a few isolated ships . . . there is no defense for placing the armor under water. It is kept there simply because it has been placed there in the past. . . . the United States has five big battleships now building, not one of them, in spite of the continued protest of our sea-going officers, with its main belt above the water-line . . . . Two of them can be altered by the pressure of outside public opinion. But that pressure must be exerted soon, or it will be too late.7

The article went on the state the long litany of defects in both warship design and naval administration that the reformers had long sought to correct: the low freeboard that put more than a third of the ship’s guns out of action in rough weather, the lack of armor protection for the crews of the medium guns, and, of course, the large, open gun ports in the turrets and the open barbettes that exposed the ship’s magazines to potential disaster.

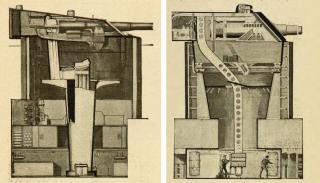

This last point was made clear with two illustrations: one showing a cross section of a typical British turret having a two-stage ammunition hoist and another showing a cross section of the typical American open turret with a single, continuous hoist. In the British design the ammunition was delivered using a hoist from the magazines to a handling room just below the gun house, and then up to the guns using a second hoist. The important feature was that the hoists were located inside enclosed trunks that protected the vulnerable powder bags from flarebacks, electrical sparks, or flames and hot splinters from enemy hits on the turret itself. By contrast, in the U.S. design the powder and shell traveled directly from the handling room at the base of the turret to the guns in an open car. According to Reuterdahl, this design violated a first principle in use since the days of fighting sail:

Primitive common sense demands that there must be no passageway straight down from the fire of the guns on the fighting-deck to the magazine. The open turret of the United States battle-ship is the only violation of this principle in the practice of the world.8

Reuterdahl claimed that he had no animus toward the Navy—in fact, just the opposite. He praised President Roosevelt’s attempts at reform, but those attempts had failed largely due to the intransigence of Congress and resistance from a well-entrenched Navy bureaucracy. Reuterdahl felt compelled to bring these issues to public notice:

I am exposing nothing whatever that the naval authorities of other countries do not already know. I am telling no national secrets to foreigners. I am merely informing the American public of conditions which it should have known of long ago; and my only hope is that, knowing them, it will correct them.9

The press had a field day with the controversy the article produced, and summaries of its contents were published in many newspapers. Rear Admiral Caspar F. Goodrich was quoted as saying that, while Navy regulations forbade him making criticism, they did not prevent him from agreeing with the article: “I will say this much, that Reuterdahl knew what he was talking about.”10 The tragic loss of his son in the Georgia accident added poignancy to Goodrich’s comments.

Reuterdahl’s article also was met with favor by most of his shipmates, and he continued with the Great White Fleet as it made stops in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, and Punta Areas, Chile, sending back his charcoal-and-watercolor illustrations for Collier’s Magazine. He left the fleet at Callao, Peru, to deal with an illness in his family, at which point the furor over his article had reached its peak.11

Blowback

The political repercussions were quick in coming. Senator Hale called for an investigation by his committee into the charges; it was scheduled for February 1908. Before the committee convened, he met with Admiral George A. Converse, president of the Board of Construction and a former bureau chief, and Rear Admiral Washington L. Capps, chief of the Bureau of Construction and Repair, to build a case for the refuting of the charges in the article. When the committee convened, Converse and Capps were interviewed first, and they vigorously defended their design decisions, claiming that the ships were as good as any, and no worse than most. The committee heard additional corroborative testimony from other officers, all of whom had worked in the bureaus at one time or another.

The committee then took testimony from Sims, Captain Bradley Fiske, Commander Albert L. Key, and others who verified the claims made in the article. Key’s testimony was damning, as he had extensive knowledge and copious statistics to document the claims. The committee had treated the previous testimony by the insurgents as mere opinion and hearsay from malcontents, but now Key provided charts and tables documenting the fact that U.S. warships routinely operated in overdraft condition, i.e., with the armor belt submerged, and compared them unfavorably with British ships of similar displacement.12 His testimony was cut short when he began to critique the bureau system. The committee went into executive session—and then abruptly adjourned without explanation.13

No report ever was made beyond a transcript of the hearings, and no conclusions were reached; clearly, Hale and the bureau chiefs hoped the matter would quietly go away.

Battleship Conference at Newport

Commander Key, however, had the bit in his teeth and would not be so easily silenced. Observing the construction of the latest of the Navy’s new dreadnoughts, the USS North Dakota, Key was concerned that the same old mistakes were being repeated. In a letter to the Secretary of the Navy, he maintained that the secondary battery was too close to the waterline and poorly protected. The barbette of the Number 3 turret was located between engine rooms, and the adjacent powder magazine was surrounded by steam pipes that could overheat the powder to a dangerous level. The current 12-inch guns were inferior to those of the same caliber in the Royal Navy.

The Secretary forwarded the letter to the Bureau of Construction, where it sat. Key had copied Sims on his report, and now Sims sent it to the President. At Sims’ urging, Roosevelt convened a meeting of the General Board, the bureaus, and the dissenting officers at the Naval War College to consider the issues. With Roosevelt presiding, the Battleship Conference met with great fanfare in Newport, Rhode Island, on 22 July 1908.

Once more, testimony from the insurgents was pitted against that of the experts of the bureaus. While those present acknowledged that the points brought forth by Key were “undesirable,” the majority decided that it would take too much time to modify the ships then under construction or even to modify the design of the next scheduled class. President Roosevelt, nearing the end of his second term, no longer had the political capital to confront Senator Hale and the Navy bureaucrats. It would not be until the New York class of 1911 that larger, 14-inch guns were installed, and not all the defects were corrected until the General Board directed the design of the “New Standard” Nevada-class ships in 1912.

However, the shortcomings of the bureau system had seen the light of day and would be largely corrected under Secretary George Von L. Meyer during the Taft administration. Finally, in March 1915, Congress established the position of Chief of Naval Operations, which placed the bureaus under the supervision of the ranking flag officer of the Navy.

Reuterdahl’s article played a vital role in helping the insurgents bring their case to the American public and begin the process of reform in the U.S. Navy. He continued to write on naval subjects, illustrate, paint, and teach art. He joined the new U.S. Navy Reserve Force at the outbreak of World War I and eventually attained the rank of lieutenant commander.

During the war, Reuterdahl worked on promoting naval recruitment, created some famous recruitment posters, and developed dazzle camouflage for ships. He documented the first transatlantic flight by Navy flying boats in May 1919 and was instrumental in the design of the first naval aviator wings insignia.14 He died at age 55 in 1925 and is buried alongside his wife, Pauline, in Arlington National Cemetery.

1. See James R. Holmes, “Why Deterrence Failed, The Imperial Japanese Navy, Strategic Memes, and the Great White Fleet,” in Forging the Trident: Theodore Roosevelt and the United States Navy, John B. Hattendorf and William P. Leeman, eds. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2020).

2. See J. M. Caiella, “ The Brick Battleship,” Naval History 35, no. 1 (February 2021): 58.

3. Elting E. Morison, Admiral Sims and the Modern American Navy (New York: Russell and Russell, 1942), 182.

4. James R. Reckner, Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2001), 68.

5. Elting E. Morison, Men, Machines, and Modern Times, 50th Anniversary Edition (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 38.

6. Morison, Admiral Sims, 181.

7. Henry Reuterdahl, “The Needs of Our Navy,” McClure’s Magazine 30, no. 3 (January 1908): 252.

8. Reuterdahl, “The Needs of Our Navy,” 254.

9. Reuterdahl, “The Needs of Our Navy,” 263.

10. “Goodrich on the Navy,” New-York Tribune, 30 December 1907.

11. Reckner, Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet, 73.

12. Hearings Before the Committee on Naval Affairs, United States Senate, on the Bill S.3335, “On Alleged Structural Defects in Battleships,” 9–11 March 1908, 291–326.

13. Morison, Admiral Sims, 197.

14. Roy A. Grossnick, United States Naval Aviation, 1910–1995 (Washington, DC: Naval Historical Center, 1997), 655.