On a cool June day, British foreign correspondent Maurice Low visits the Pacific theater to report on the sizzling geostrategic competition between the United States and a rising Asian power. Neutral countries are watching “the growing friction . . . with keen interest,” Low reports. They and the whole “world” anticipate a “coming . . . struggle for the mastery of the Pacific.”1

The prospective combatants concur. The U.S. President has been “fully alive” for more than a decade “to the danger” from this rising power, whose leaders understand the risk of conflict and conceitedly predict the outcome.2 “The United States of America may be the most wealthy country in the world,” one of their diplomats has told The Washington Post, “but she has not a sufficient protection for defense on the Pacific should the two nations come to hostilities.” Fanning the embers of war, one of the rival power’s jingoistic newspapers has declared its people are ready to defeat the United States by “strik[ing] the devil’s head with the iron hammer for the sake of civilization.”3

Although these events bear a striking resemblance to today’s emerging great-power competition (GPC) between Washington and Beijing, this rivalrous saber-rattling occurred more than a century ago—between the United States and Japan during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Akin to Imperial Japan, contemporary China dreams of becoming Asia’s dominant power and revising the international order to favor its Pacific-focused interests.

Such ambitions, however, demand “a powerful and modern navy,” as Chinese leader Xi Jinping acknowledged in 2017.4 Emulating the early 20th-century Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has developed sea denial strategies “to push U.S. sea…forces away from the East Asian coastline” and compromise America’s ability to defend Taiwan.5 If successful, Chinese ambitions would topple seven decades of American hegemony in the first island chain and the Pacific.

Historical analogies are always imperfect, and this one is no exception. Nonetheless, Theodore Roosevelt’s naval strategy during America’s fin de siècle GPC (primarily against Japan as well as Great Britain and Germany) illuminates how today’s U.S. Navy can sustain maritime superiority to manipulate Beijing’s decision calculus against invading Taiwan and establishing hegemony in the First Island Chain.

After defeating Spain in 1898, the United States no longer could remain isolationist. Its territorial acquisitions in the Pacific and bursting economic activity necessitated greater involvement in world affairs. It also meant the nation would clash with other great powers over conflicting ambitions. To protect American interests without having to fight, Roosevelt “promot[ed] peace” with other powers via deterrence, which required “keeping our Navy so strong that war may not come or that we may be successful if it does come.”6 Roosevelt strengthened the Navy by prioritizing preparedness, reorganization, training, and “armed diplomacy.” His efforts transformed the United States from a middling power with a toothless navy to a great power with the world’s second-most powerful navy. Roosevelt “did not . . . bring about this evolution single-handedly,” as one scholar noted.7 But he did engender the U.S. Navy’s “coming of age,” securing America’s interests in the Pacific—and beyond.

An Ounce of Prevention

Roosevelt’s first foray into naval affairs, his 1882 book The Naval War of 1812, underscored the importance of naval preparedness. According to Roosevelt’s historical interpretation of the conflict, the Royal Navy had defeated America’s Navy because the latter had prepared poorly. If the U.S. fleet had been properly manned, trained, and equipped, it could have deterred British aggression, averted the war, or at least waged a fairer fight. Roosevelt applied these lessons to his own era, concluding that American naval power must be strengthened. He found the Navy in 1882 “a disgrace to us as a nation.”8 Fortunately, building and maintaining a naval force was “the very lightest premium for insuring peace which this nation could possibly pay.” Six years later, in his address to the New York–based Union League Club, Roosevelt urged policymakers to “prepare a navy capable of upholding the honor of the nation.”9

As President, Roosevelt practiced what he preached by establishing and hardening U.S. naval bases in the western Pacific—particularly in Subic Bay. During a hypothetical Japanese invasion, the base fortifications would shield U.S. forces from attack as they stalled the offensive and awaited Atlantic Fleet reinforcements. “If we are to have a fleet in the Asiatic waters, or to expect the slightest influence in Eastern Asia,” Roosevelt reasoned, “then it is of the highest importance that we have a naval station at Subic Bay.”10 An avid fan of American football, Roosevelt also knew that the best defense was a good offense. When, in December 1907, muckrakers and junior naval officers reported design flaws in America’s newest battleships, Roosevelt convened a commission of ship designers, admirals, and junior officers at the Naval War College (NWC) to opine “whether any or all of these defects can be remedied” and how to improve future designs.11

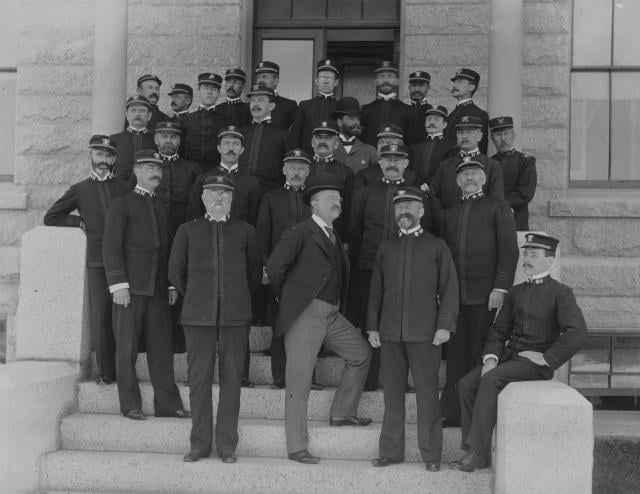

Moving from matériel to manpower, Roosevelt reformed professional selection and development. He encouraged the foundation of the Navy League to “educate” citizens and “support” the “sea services.” He sought intrepid commanders like Admiral David Farragut, who “offered an example . . . of courage and daring, of readiness to assume responsibility . . . [and] for taking thought in advance.” And when he found such leaders, he interfered in the promotion process. As Assistant Secretary of the Navy, he handpicked George Dewey to command the Asiatic Squadron because he was a skilled leader who met “the needs of the situation in whatever way is necessary.”12

Putting the ‘War’ in Warship

When Roosevelt became President, the Navy had been neglected since the Civil War. In that war, the Navy largely executed littoral operations, removing the need for blue-water capabilities. Roosevelt refocused the Navy’s composition and capabilities toward sea control to ensure the United States won potential GPC engagements.

His efforts began in May 1897 when he asked NWC students to tackle a “Special Confidential Problem”: war with Japan. If the calamity occurred, Roosevelt wanted to know “[w]hat force will be necessary to uphold the intervention, and how shall it be employed?” Unsatisfied with the NWC’s conclusions, Roosevelt retorted that “the determining factor in any war with Japan would be control of the sea.” He added: “I think our objective should be the Japanese fleet.” When confusion later arose in his presidential administration on how to achieve “sea control,” Roosevelt accepted Admiral Dewey’s 1904 assessment that it entailed massing “sufficient strength to keep the sea and to meet the enemy at sea.”13

For more than a decade afterward, Roosevelt resized and restructured the U.S. Navy to control critical Pacific sea lanes and destroy rival fleets. His reforms depended on more ships, specifically, battleships, which he believed “the strength of the navy rest[ed] primarily upon” because, as Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan explained, they gave and received “hard knocks” against the enemy. In 1897, he wanted Congress to triple the number of battleships and increase the number of large cruisers from 16 to 22. He loosely based his request on Mahan’s “broad formula” for calculating adequate fleet strength, which matched each U.S. fleet with “the largest force likely to be brought against it.”14

In office, Roosevelt increased the Navy’s budget and force strength exponentially. Next, however, he had to prove the worth of these investments.

Multidimensional ‘Practice Cruise’

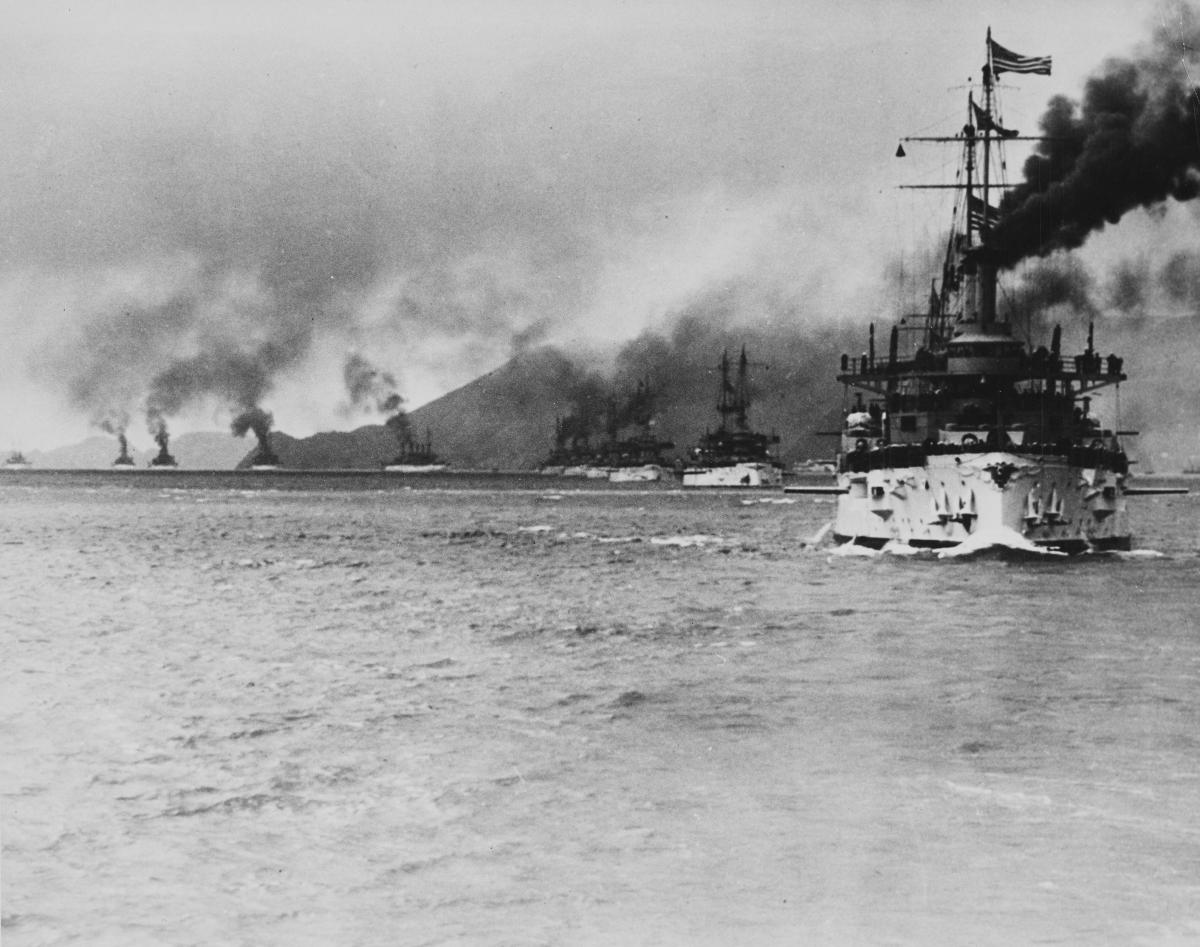

At 0800 on a clear Monday in December 1907, President Roosevelt dispatched 16 U.S. Navy battleships, gleaming with bright white paint, to steam 46,000 miles and circumnavigate the globe. Tipping his hat to each battleship as they steamed past him firing a 21-gun salute, Roosevelt grinned: “Did you ever see such a fleet and such a day?” When the last ship passed, and the fleet disappeared over the horizon, the presidential yacht lowered its signal flags, which read: “Proceed on your assigned duty.”15

But what was this Great White Fleet’s “assigned duty?” In his 1913 autobiography, Roosevelt said the cruise’s “prime purpose” was to “impress the American people.” He had recently submitted a congressional request for a larger budget and battleship force after Britain debuted the highly technical HMS Dreadnought a year earlier. To further excite the American people, and thus persuade Congress to approve the request, Roosevelt established a press center on the USS Connecticut to “feed information” to the reporters on board so they “would file patriotic copy with their editors back home.”16 And just as the Atlantic Fleet docked in San Francisco and 8,000 sailors marched in a parade with 500,000 enthusiastic spectators, Congress began debating Roosevelt’s proposed naval appropriations bill. Congress increased the Navy’s budget and authorized more battleships in no small part, Roosevelt believed, to the cruise’s public relations campaign.

Roosevelt also deployed the Fleet to stress-test the new Navy. “I want all failures, blunders and shortcomings to be made apparent in time of peace and not in time of war,” Roosevelt told a friend. The “practice voyage” paid off by revising strategic planning estimates. The Navy discovered that it could respond to an emergency in East Asia in 90 days—not 120, as previously assumed—and it could do so fully operational without needing to “pause for repairs, refueling, or maintenance.”17 Additionally, sailors returned from the cruise with greater readiness than when they had left because of the constant drill and target practice. Roosevelt had tested the fleet. It exceeded his expectations. But how would he use it?

“A Man-of-War is the Best Ambassador”

Days before sending off the Great White Fleet, Roosevelt told a gathering in Hampton Roads, Virginia, “that battleships are mighty good peacemakers.”18 The cruise was practice, but also a deterrent.

Roosevelt viewed Imperial Japan with heightened apprehension after it defeated Russia in 1905. He feared Tokyo officials “might get the ‘big head’ and enter into a general career of insolence and aggression.” As riots in Tokyo broke out over “unfair” peace treaty terms with Russia and California’s discrimination against Japanese students, Roosevelt fretted “over this Japan situation more than almost any other.” So he decided to send the fleet around the Pacific “to impress Japan with the seriousness of the situation” and deter their aggressive ambitions.19

Earlier in his administration, Roosevelt had sent naval “show[s] of strength” in two other instances: first, to deter the Germans from overthrowing the Venezuelan government over unpaid debts in 1902; and second, to deter the Colombians from reasserting control over Panama in 1903 after the former province declared independence. In each situation, Roosevelt paired naval force with an olive branch and a face-saving exit plan for adversaries—and it succeeded. Germany and Colombia accepted Roosevelt’s demands. And “every particle of trouble with the Japanese government,” Roosevelt later reminisced, “stopped like magic” after he deployed the Great White Fleet.20 The Navy, then, was a critical component of Roosevelt’s “armed diplomacy” approach, which contained three principles:

1. Speak softly and carry a big stick. Roosevelt’s soft speaking meant avoiding “bluster.” He wanted “all foreign powers to understand that when we have adopted a line of policy we have adopted it definitely, and with the intention of backing it up with deeds as well as words.” Roosevelt believed that “little powers” rarely accomplished anything in foreign affairs “because they lack the element of force behind their good wishes.” Without naval force, diplomacy was useless. When Japan became belligerent, Roosevelt tried “to be polite to the Japanese.”21 But when the Japanese mistook his kindness for fear, he concluded “it was time for a show down” and sent the fleet.

2. Match geopolitical objectives with naval means. Whenever Roosevelt perceived an endangerment of U.S. interests, he deployed the Navy—with its “mobility, versatility, and lethality”—because it could “right-size” itself “to the scope of the situation it was dispatched to confront,” as naval historian Henry Hendrix explained. To deter Germany, Roosevelt sent nearly the entire Atlantic Fleet; to deter Colombia, he deployed a handful of small cruisers.22

3. Don’t bluff. Roosevelt applied old “frontier” principles to foreign affairs: “Don’t flourish your revolver and never draw unless you intend to shoot.” Refusing to enforce a red line, Roosevelt believed, was “the one unpardonable sin” because it destroyed a nation’s most valuable currency on the world stage: credibility.23 When Roosevelt gave Germany ten days to leave Venezuela and the Germans refused, he dispatched U.S. warships.

Lessons for Today

Twelve years before assuming the presidency, Roosevelt considered it “too late to make ready for war when the fight has once begun.”24 True to his word, he spent his Assistant Secretaryship and Presidency readying the Navy. To sustain U.S. maritime superiority, the Navy today should heed Roosevelt’s policies from another era of GPC.

Preempt an American victory through preparation. Cultivate and recruit talented personnel by increasing ROTC throughputs and coordinating with the Navy League to host recruiting events. Prioritize GPC language and cultural aptitude at officer training commands. Change O-5 promotion board precepts to incentivize officers to pursue a career track that includes Indo-Pacific experience, a Foreign Area Officer billet, or exchange programs with foreign navies and U.S. government agencies.

For naval assets, establish rotating, fortified partner facilities in the First Island Chain to supply and sustain operational naval forces during an emergency. Convene commissions to identify and mitigate delays and deficits for the Ford-class carriers, Zumwalt-class destroyers, and littoral combat ships. Hold more joint war games to determine what the Navy and other forces need to defend Taiwan from “Red” forces.

Restructure the Navy for sea control. Disrupting China’s decision processes toward Pacific aggression requires the Navy to reorganize itself with the objective of sinking the PLAN wartime fleet in the first island chain, as Roosevelt structured the Navy against the IJN fleet. The U.S. Pacific Fleet’s strength must (in Roosevelt’s words) “constantly be kept above” the PLAN’s future fleet capabilities and size.25

Since the PLAN wants 425 ships by 2030, the U.S. Navy must come closer to matching it in size or capability by building a larger but lighter force. Replace aircraft carriers and larger surface combatants with nuclear-powered light aircraft carriers (CVNEs), lightning carriers based on the America-class amphibious ships, Constellation-class frigates, and large unmanned underwater vehicles. Develop ships with operational flexibility and comfortability in China’s anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) environment. Ensure ships can give and take “hard hits” by equipping them with adequate defenses that repel cruise or ballistic missile attacks and offensive weaponry, including deck launchers and long-range missiles.

Train as you fight. Akin to Roosevelt’s “practice cruise” for the Great White Fleet, the Navy should schedule a large-scale, amphibious demonstration simulating war with China over Taiwan to stress-test U.S. forces and provide valuable information for future fleet designs, operational readiness, and other factors that could revise strategic planning calculations. Enhance popular and congressional support by inviting media outlets aboard ships to publicize the exercise and the Navy’s mission. Bolster efforts to counter Chinese propaganda during unsafe and unprofessional interactions at sea by professionalizing the training of Ship’s Nautical or Otherwise Photographic Interpretation and Examination (SNOOPIE) teams and replacing outdated camera equipment.

Deter Chinese political malpractice with “armed diplomacy.” Recognize that China is not immune to deterrence and can be persuaded to delay or indefinitely postpone its aggressive ambitions if the United States firmly pushes back against its provocations. For example, in May 2020, the Navy increased its presence in the South China Sea by deploying two aircraft carrier strike groups when the new Taiwanese president assumed office. This show of force “dampened Chinese intimidation toward Taiwan” and lessened PLAN harassment of a Malaysian-charted Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) survey ship.26 Going forward, the Navy should leverage its scalability, as Roosevelt did, to proportionally respond to Chinese aggression by pairing naval force with diplomatic pressure and a firm, but “soft,” enunciation of America’s position. These enunciations, however, must never be bluffs.

Not all of Roosevelt’s naval policies were resounding triumphs. He attributed peace with Japan to the Great White Fleet, but the reality is more opaque. He dispatched the fleet after Britain unveiled the Dreadnought and, thus, the Navy no longer possessed top-of-the-line capital ships. It’s hard to imagine the IJN found the U.S. Navy too “daunting” a competitor with outdated platforms, as Professor James Holmes notes.27 Roosevelt also impeded American naval growth by limiting battleship procurement in 1905 to quell congressional opposition. Lastly, Roosevelt faced fierce opposition in January 1909 when he proposed to remove Marines from warships and abolish the Marine Corps as a military service.

Therefore, the Navy should learn from Roosevelt’s mistakes. Utilize “shows of strength” as deterrents by flexing the most advanced technology vis-à-vis PLAN sea-denial weaponry. Avoid asking for less money, ships, or technology to appease Congress; request what the Navy needs and wants. Emulate strategic revolutions in sea power like the Dreadnought. (PLAN conscription of any seaworthy vessel to enhance Chinese maritime dominance is a recent revolution. Following suit, the Navy should deploy Coast Guard cutters to patrol allied EEZs or recruit more merchant marine vessels to enhance sealift capabilities.) Finally, leverage the Marines (and other services) to execute an interoperable counter-A2/AD strategy in the First Island Chain.

Profiting from History

In Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Long John Silver quips, “We can steer a course, but who’s to set one.” As China seeks to dominate the Indo-Pacific region, the U.S. Navy must set an innovative course to maintain maritime superiority and dissuade Beijing from scuttling American hegemony in the Pacific.

History offers such a course. Theodore Roosevelt wanted to make “the United States the dominant power on the Pacific Ocean” so it could “do the great work of a great world power.” Unfortunately, Roosevelt entered office with the Navy lying “at the mercy of a tenth-rate power like Chili [sic]” and having few warships “worthy of the name.”28

As the United States confronted other great powers at the turn of the century, Roosevelt recognized that becoming a great nation required a great navy. He “promote[d] peace,” enhanced America’s international status, and safeguarded its interests by preparing, restructuring, training, and deploying a first-rate navy. His prescription, however, was far from novel. He once said that he “profit[ed] by the lessons of history by seeing that our navy is always kept adequate to our needs.”29 We should as well.

1. A. Maurice Low, “Foreign Affairs: Japan and the Saxon,” Forum 40, no. 4 (October 1908): 307, ProQuest American Periodicals.

2. Theodore Roosevelt to Alfred Thayer Mahan, 3 May 1897, in Theodore Roosevelt, The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt, ed. Elting Elmore Morison (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1951) [henceforth, LTR], I:606.

3. “Count Okuma Declares the Pacific Coast Is at the Mercy of Japan,” The Washington Post, 13 September 1908; “Okuma for a Big Navy,” The New York Times, 3 September 1904, 4; Mainichi Shimbun, October 22, 1906 quoted in T. A. Bailey, Theodore Roosevelt and the Japanese-American Crises (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1934), 50.

4. “[Xi Jinping Inspects Navy Minister and Delivers Important Speech],” China Ministry of Defense, 24 May 2017.

5. Robert D. Kaplan, Asia’s Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific (New York: Random House, 2014), 38–39.

6. Theodore Roosevelt to Philander Knox, 8 February 1909, LTR, 6:1510.

7. Henry J. Hendrix, Theodore Roosevelt’s Naval Diplomacy: The U.S. Navy and the Birth of the American Century (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014), xvi; Kenneth Wimmel, Theodore Roosevelt and the Great White Fleet: American Sea Power Comes of Age (Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 1998), xvii.

8. Theodore Roosevelt to Henry Cabot Lodge with “Union League Club remarks” attachment, 22 January 1888, in Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, 1884–1918, ed. Henry Cabot Lodge (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), I:63.

9. Theodore Roosevelt, Message to the Senate and House of Representatives, 3 December 1901, in Theodore Roosevelt, Presidential Address and State Papers: December 3, 1901 to January 4, 1904 (New York: The Review of Reviews Company, 1910), II: 578; Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, I:63.

10. Theodore Roosevelt to Elijah Burton, 23 February 1904, LTR, IV:735–37.

11. Roosevelt quoted in Elting Elmore Morison, Admiral Sims and the Modern American Navy (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1942), 203.

12. “Who We Are,” Navy League of the United States; Henry Cabot Lodge and Theodore Roosevelt, Hero Tales from American History (New York: The Century Company, 1922), 261; and Roosevelt, Autobiography, 231.

13. Theodore Roosevelt to Captain Caspar F. Goodrich, 28 May 1897; Roosevelt to Goodrich, 16 June 1897, LTR, I:625; and ADM Dewey quoted in William R. Braisted, The United States Navy in the Pacific, 1897–1909 (1958; reprint, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008), 177.

14. Theodore Roosevelt to George Edmund Foss, 11 January 1907, V:544; Alfred Thayer Mahan, The Interest of America in Sea Power (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1898), 198; Roosevelt to John D. Long, 30 September 1897, LTR, I:694–95; and Mahan, Interest of America in Sea Power, 198.

15. Roosevelt quoted in Wimmel, Theodore Roosevelt and the Great White Fleet, xiv–xv.

16. Roosevelt, Autobiography, 593–95; David Milne, Worldmaking: The Art and Science of American Diplomacy (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015), 65–66.

17. Theodore Roosevelt to Henry Cabot Lodge, 10 July 1897, LTR, V:708; Challener, Admirals, Generals, and Foreign Policy, 40.

18. “President Quick to Avert Danger,” Boston Daily Globe, 27 April 1907.

19. Theodore Roosevelt to Cecil Spring Rice, 13 June 1904, LTR, IV:830; Roosevelt to Elihu Root, 13 July 1907, LTR, V:716; and Roosevelt quoted by Sir Claude M. MacDonald in letter to Sir Edward Grey, 17 March 1908, in British Documents on the Origins of the War (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1932), VIII:457–58.

20. Theodore Roosevelt to Sir George Trevelyan, 1 October 1911, LTR, VII:394.

21. Roosevelt quoted in Howard K. Beale, Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power (1956; reprint, New York: Collier Books, 1967), 50; Roosevelt to Theodore Elijah Burton, 23 February 1904, LTR, IV:734–36; and Roosevelt to Sir George Trevelyan, 11 October 1911, LTR, VII: 393.

22. Hendrix, Theodore Roosevelt’s Naval Diplomacy, 169–71.

23. Theodore Roosevelt to Henry Cabot Lodge, 27 March 1901, in Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, 1884–1918, ed. Henry Cabot Lodge (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), I:486.; Roosevelt quoted in Frederick W. Marks III, Velvet on Iron: The Diplomacy of Theodore Roosevelt (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1979), 152.

24. Theodore Roosevelt, “Washington’s Forgotten Maxim,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 23, no 3 (July 1897):

25. Theodore Roosevelt to John D. Long, 30 September 1897, LTR, 1:694.

26. Brent Sadler, “Toward a New Naval Statecraft,” Defense One, 16 May 2021.

27. James R. Holmes, “Why Deterrence Failed: The Imperial Japanese Navy, Strategic Memes, and the Great White Fleet” in Forging the Trident, 226.

28. Quoted in Beale, Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power, 50; Theodore Roosevelt to Henry Cabot Lodge, 22 January 1888, in Selections from the Correspondence of Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, 63.

29. Roosevelt, “Washington’s Forgotten Maxim”; Roosevelt, “Speech at Mobile, Alabama, October 23, 1905,” Presidential Addresses, 4:517, quoted in Smith, “Profit by the Lessons of History,” 236.